.

With the Adam Art Gallery closed for the holidays, and Te Papa’s art spaces and City Gallery closed for renovations, the Dowse Art Museum’s Gavin Hipkins survey show The Domain feels like the only show in town. If you’re in Wellington, needing a contemporary-art fix, it has to be The Domain. And it’s well worth the trip out to Lower Hutt.

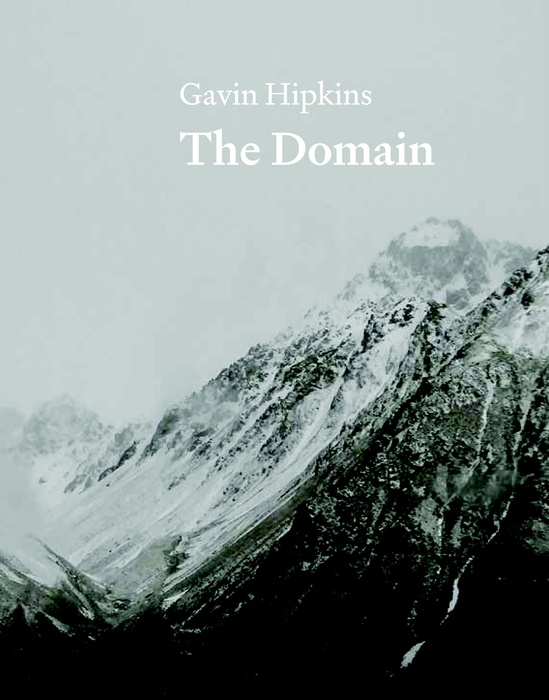

The show covers some twenty-five years of the photographer-filmmaker’s work and it’s accompanied by a door-stopper tome, courtesy Victoria University Press. The curatorial baby of Dowse Director Courtney Johnston, the show fills the Museum’s ground-floor galleries. That’s the most space the Dowse has ever devoted to such a show. It’s great to see it bite the bullet and make such a commitment to one artist.

With such shows, the stakes are high for museum and artist alike. Big retrospectives can go either way. In gathering work, they can reveal the breadth of an artist’s achievement or expose their weaknesses. There are many stories of artists unable to re-enter the studio after their big show. The Domain certainly shifted my sense of Hipkins’s work.

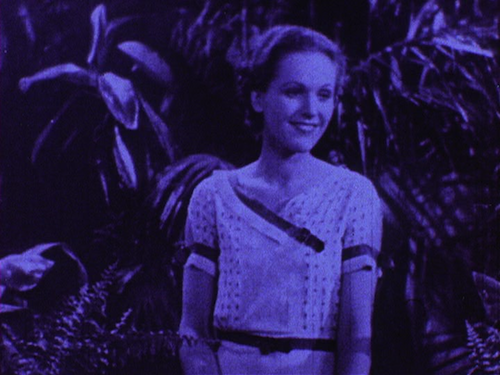

Hipkins has long been known as a ‘tourist of photography’, meaning two things: he’s a photo tourist (photographing things on his excursions) and a tourist of the medium itself (exploring its histories and styles). Or, as Peter Brunt put it, Hipkins is ‘an iconographer of desire, travel, time and … modern communities’, and ‘a great manipulator of the photographic artifact itself: its materiality, formats, systems, modes of installation and display’. In other words, the project is all about a dance of content and form, and you never quite know which is taking the lead.

Accounts of Hipkins’s work emphasise its eclecticism—its traversing diverse styles and subjects, histories and geographies—but what impresses with The Domain is the consistency of tone. You realise that every work is a piece in a larger cross-referenced puzzle—a Hipkins universe—and that that’s always been the case. But it took this show to reveal that. In the work, there’s a tension between its eye-candy lightness, its variety, and its novelty, and its persistent, inescapable melancholy—a haunting sense of déjà vu. And Hipkins cross-references it all with his big-picture themes: the legacies of modernism, colonialism, and other grand schemes. Hubris.

In our current research-art epoch, Hipkins is a novelty. His practice may be bookish—driven by thinking about history and art history—but he’s also a consummate stylist, with a deft touch. He lets the format do the heavy lifting. He makes it look easy. He turns everything into art. Catch The Domain before it closes. (Dowse Art Museum, Lower Hutt, until 25 March.)

•