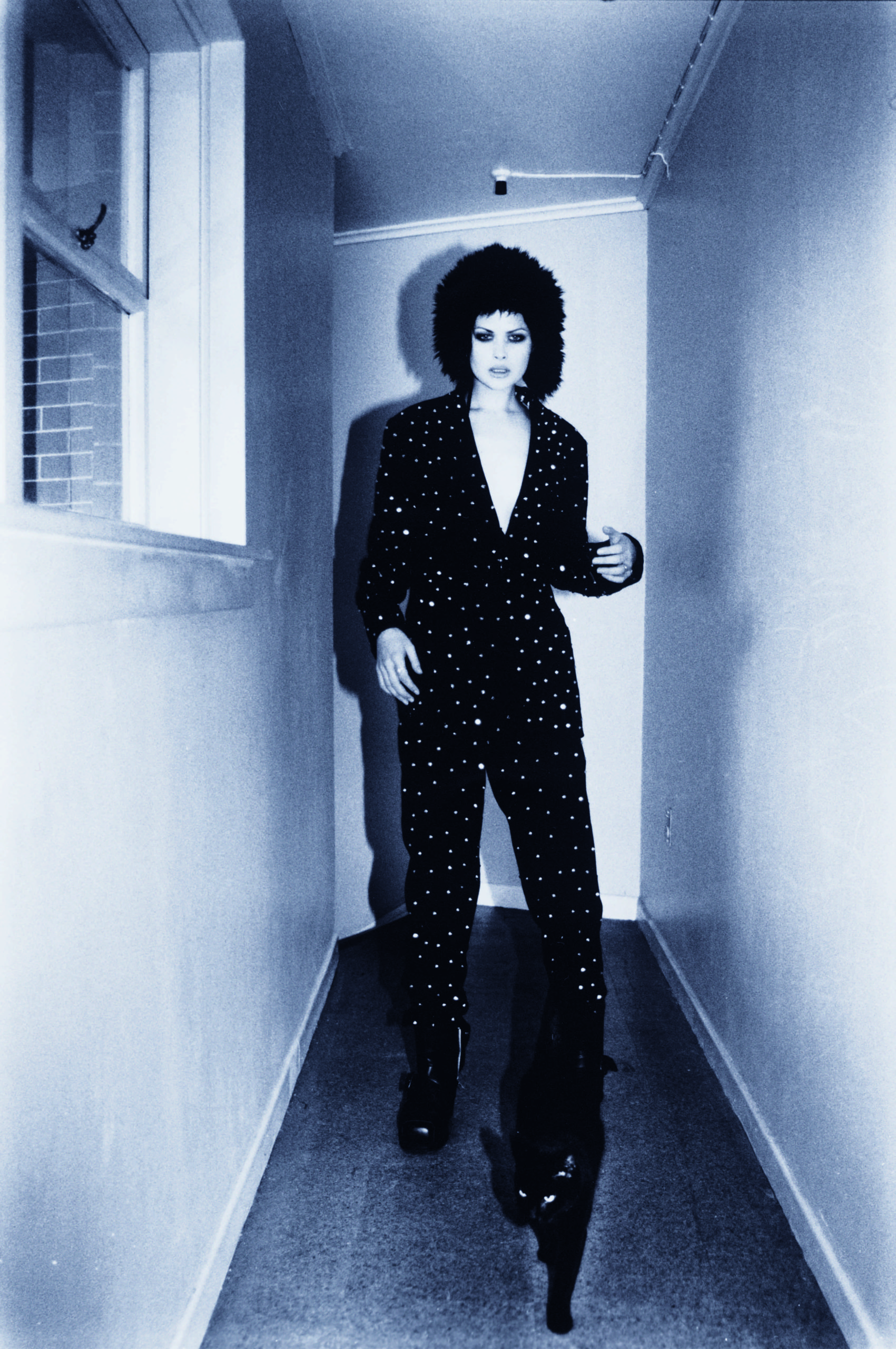

Come and see my new show, It’s Personal, presenting the New Zealand photography collection of former ad man Howard Greive and photographer Gabrielle McKone. The Wellington couple began collecting New Zealand art in the 1980s, but fifteen years ago they decided to focus exclusively on photography. Greive says, ‘Maybe it’s years in advertising but a sharp, single-minded proposition always works. And, for us, that SMP was photography.’ Their place is packed to the gills with photographs ranging from expressive to conceptual, documentary to directorial, but they don’t spread their bets, preferring to collect key figures in depth. The show features works by Edith Amituanai, Janet Bayly, L. Budd, Joyce Campbell, Gavin Hipkins, Jae Hoon Lee, Anne Noble, Peter Peryer, and Yvonne Todd. There’s also a cluster of gems from earlier figures: Theo Schoon, Ans Westra, and Gary Baigent. Join us for the opening preview, Tuesday 9 August at 6pm; and for the closing-day talk, on Sunday 21 August at 11am, presented in conjunction with Photobook/NZ. It’s Personal: The Howard Greive and Gabrielle McKone Photography Collection, Webb’s Wellington, eleven days only, 10–21 August 2022.

[IMAGE: Yvonne Todd Wet Sock 2005]

•

Premature

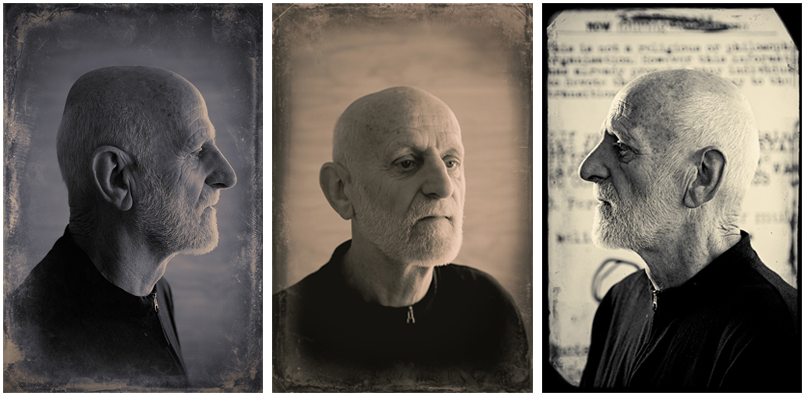

Clinic of Phantasms, my collection of Giovanni Intra’s writings, is at the printers, but has already been reviewed by Jennifer Bornstein for Contemporary Hum here.

[IMAGE: Monty Adams Allannah Wears Studded Suit by Giovanni Intra … 1994]

•

Make It So

Luit Bieringa died this week. He was a big figure in my life. In 1985, when he was Director of the National Art Gallery, he gave the kid a break, appointing me as the Gallery’s first curatorial intern. Back then, I was a feral mess, unsuited to institutional life, however, against advice, he tolerated me, supported me, sheltered me, parented me. After my internship, he gave me a job as curator of contemporary New Zealand art. It set me on my life’s course. I can’t imagine where I would have been otherwise.

Bieringa was an art missionary, working at the coal face, taking art to the disbelievers. In 1971, he started off as the director of a small regional space, the Manawatu Art Gallery in Palmerston North. When he arrived, it was in a house; when he left, it was in a new purpose-built museum. While he was there, he mounted important shows of McCahon and Woollaston (the subjects of his master’s art-history thesis, New Zealand’s first) and The Active Eye (a survey of New Zealand photography). He had a can-do attitude. He was limited by time and money, but never by lack of vision.

In 1979, Bieringa was given the reins at Wellington’s National Art Gallery and blew the dust off. He professionalised things: building up the staff and facilities, growing the collection and mounting impressive shows. He gave the old NAG a contemporary edge and relevance. By the time I arrived, the place had real momentum. It felt like a sandpit full of toys. And that was my introduction to curating.

In 1986, when Bieringa’s plans to develop a new National Art Gallery were thwarted, he created Shed 11, a contemporary-art annex on the waterfront, and presented audacious shows like Wild Visionary Spectral: New German Art, Content/Context, Barbara Kruger, and Cindy Sherman.

But, in 1989, after ten years, Bieringa’s directorship hit a wall. He found himself at loggerheads with the Museum of New Zealand project—which he had inadvertently kick started. It had developed a life of its own, and was out to kill its maker. Now an impediment, Bieringa was dismissed. Unfairly, said the judge. In 1992, Shed 11 was closed. It was the end of the golden weather. The city lost not only a physical space for showing art, but also a symbolic space for speculation. Luckily, Wellington City Art Gallery would pick up the slack.

Beiringa dusted himself off. He stayed in Wellington. He went on to do important exhibition and publishing projects as a freelancer, and with wife Jan reinvented himself as a filmmaker, making insightful documentaries on Ans Westra, Peter McLeavey, Gordon Tovey, and, most recently, Theo Schoon. But I often wonder what he might have achieved—what we all might have achieved—if he had continued as a museum director, if he had retained that leverage.

I’ve really got to know Bieringa again properly only in the last year or so. We’ve been working together on a book project about Shed 11, which has been a walk down memory lane. It has reminded me what a vital art scene Wellington had in the late 1980s, when the National Art Gallery and Wellington City Art Gallery were both expanding and egging each another on, and new art ideas were fermenting. I don’t think it would have happened without Bieringa. It wasn’t just what he did, it’s what he enabled others to do. He was a catalyst.

•

Alice

Walking to work, he used to pass her every day, going in the opposite direction. She didn’t seem so interesting at first, but he became increasingly curious about her. He started to look forward to seeing her. He became attentive to details, to the way she moved, to what she was carrying, what she was wearing, her ever-changing moods. Even though they never spoke, he became a little obsessed. Then, when he confessed his fascination to a friend, they said, ‘Oh, that’s Alice; everyone thinks she’s amazing’, and he was gutted. He thought something special in her spoke to something special in him. He thought he alone was alert to her charms and would champion them. I think often that’s how good art works, how it wheedles its way into our heads and gets under our skin. It doesn’t address us directly but our engagement with it builds over time, gently, inevitably. We think we have some special, privileged rapport with it, that our appreciation of it makes us unique, that we picked it out of the crowd. We feel flattered that we noticed it, that we ‘get it’, only to find it has the same effect on almost every one.

•

John Lethbridge Rides Again

.

Come and see my latest show—John Lethbridge: Divination: Performance Photographs 1978–82 at Webb’s new space in Marion Street, Wellington (until 23 April 2022). Lethbridge featured in Action Replay: Post-Object Art—a series of shows I curated with Tina Barton, Wystan Curnow, and John Hurrell back in 1998—and has been on my mind ever since. It’s great to finally do this show.

Born in Wellington, Lethbridge started out as a printmaker, but went on to study under Jim Allen at Elam in Auckland in the early 1970s, joining the post-object-art set. (His show Formal Enema Enigma was part of Auckland City Art Gallery’s 1975 Project Programme.) He moved to Australia at the beginning of 1976 and bought a Hasselblad camera. The iconic staged photographs he made in the late 1970s and early 1980s have one foot in the literalism of performance documentation and another in the glitz of fashion photography. Equal parts Joseph Beuys and Helmut Newton, they scrambled genuine psycho-spiritual enquiry with camp theatrics, and epitomised the postmodern turn.

Many of Lethbridge’s photos feature performer–assistant Jane Campion. His 1978 series Farm Life: An Exercise in Survival was shot at her family farm at Peka Peka. It includes The Ride, showing a gender-bending Campion riding a saddle mounted on a stepladder, carrot in one hand, riding crop in the other. Tally ho! Essay here.

.

[IMAGE: John Lethbridge Farm Life: An Exercise in Survival: The Ride 1978]

•

Thoughts that Count

.

Thank you to Carey Young for dedicating this day of the Hilma Af Klint show at City Gallery to me. Brought tears to my eyes.

•

Enough about Me

.

Andrew Paul Wood exit interviews me for The Big Idea. Thanks Andrew.

•

Four Paragraphs

.

Years ago, I received some sage advice from an older curator: every letter needs four paragraphs. Paragraph 1: Flatter yourself. Paragraph 2: Flatter the person you’re writing to. Paragraph 3: Flatter yourself and the person you’re writing to—link your fortunes. Paragraph 4: Ask for what you want. My mentor explained that letter writers routinely omit one of these paragraphs (perhaps mistakenly taking it for granted), bewildering their reader. They fawn over them, but themselves seem unworthy. Or they sing their own praises exclusively. Or they fail to connect. Or they forget to even ask for what they want, missing their own point. It struck me that this four-paragraph approach was good not only for writing letters but for relating to others in general—being empathetic while hanging onto your self, and considering the stake they may have in what you want (or not).

.

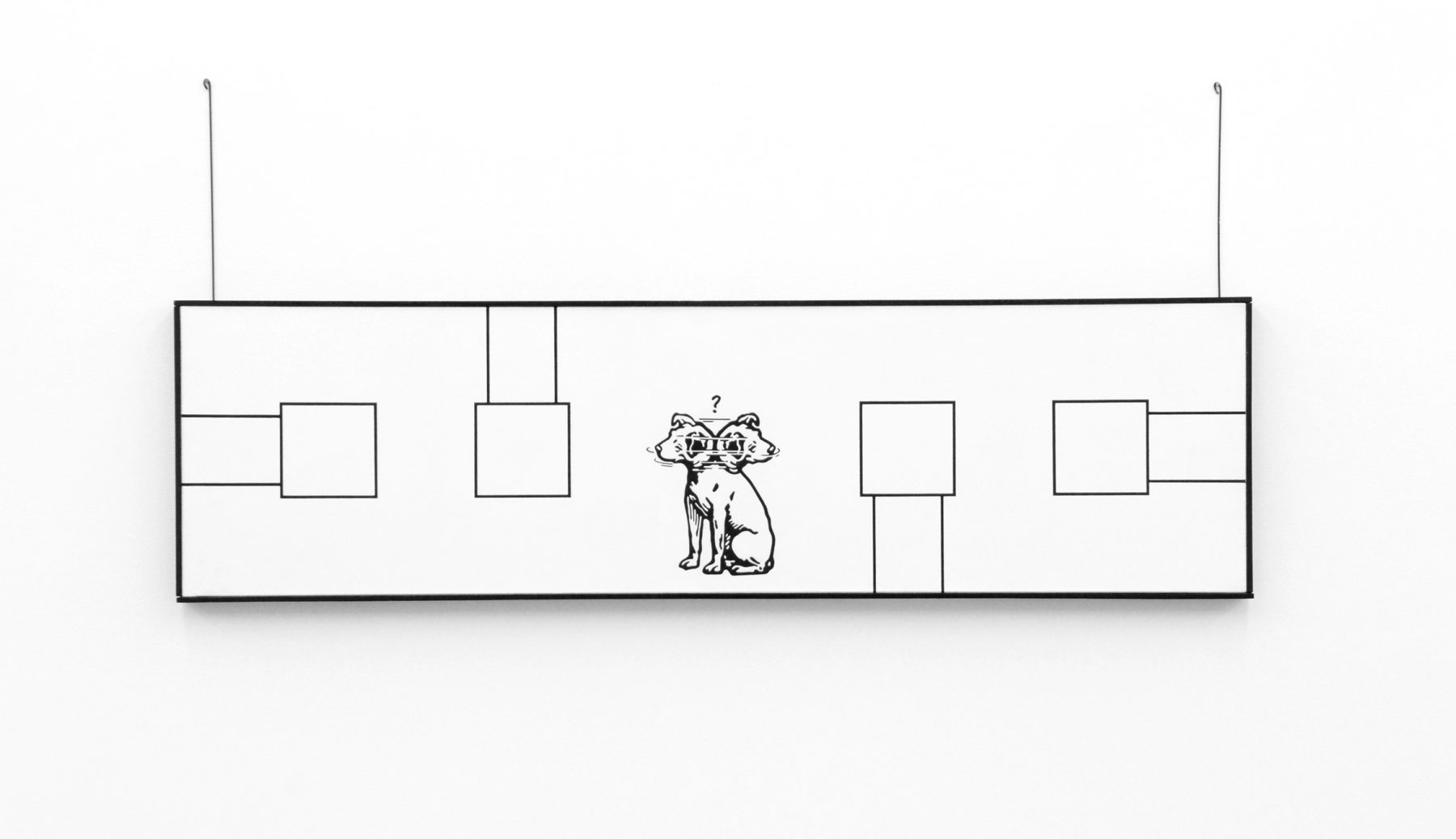

[IMAGE: Peter Tyndall]

•

Late Great

.

American conceptual artist Lawrence Weiner is with us no more. Here’s a magnificent wall-text work he did for my show Grey Water at the Institute of Modern Art, Brisbane, in 2007. On the floor is a work by Bill Culbert, also departed. So pleased to have worked with them both.

•

Frog Poet

.

These days, I receive few invitations to weddings, but many to funerals. Too many. I was sad to hear of the recent death of Robert MacPherson, a giant of the Brisbane art scene. True, he had a good innings—he was eighty-four! MacPherson was a complex, eccentric artist, who jumped many art-category fences, scrambling formalism, conceptualism, and folksy Aussie vernacularism. He was at once an internationalist and a localist. He did a poignant show for me at the Institute of Modern Art, back in 2007. Popov and the Lost Constructivists filled the big gallery with his constructivist-inspired junk assemblages. These were accompanied by death notices from the local newspaper glued to drops of receipt-printer paper. (He had started by cutting out obits for Russian immigrants, but expanded to include others with nicknames.) The work implied that countless Russian émigré constructivists may have been working incognito in Brisbane backyard sheds. Of course, MacPherson himself did not toil in obscurity. Today, he pretty much permeates Australian art history. He was a big wheel.

.

[IMAGE: Robert MacPherson: Popov and the Lost Constructivists, Institute of Modern Art, Brisbane, 2007.]

•