Years ago, I was in a marketing workshop. It focused on a case study: promoting a fancy new biscuit. The instructor explained that the target market had been time-poor solo mums, hankering for a daily treat, an affordable luxury. But what to call the biscuit? They resembled Melting Moments, so he called them simply ‘Moments’. Tagline: ‘Give yourself a moment.’ He framed the biscuit as an opportunity for miserable moms to press the whole world—including their absent partners and over-present kids—out of the frame, and attend to themselves for a change. And, as people are suggestible, perhaps it worked, perhaps it became the reward: a temporal interruption in tablet form, a sugar pill, permission to enjoy. I was in two minds about the presentation, which felt cynical. Our instructor seemed to deeply understand the mindset of solo mums, but in order to exploit it. Understanding can assist us in helping others, but also in helping ourselves. Perhaps the instructor would say: everyone wins. I’m not so sure.

•

Judgement Day

Here I am, at the Scott Redford art giveaway, outside GOMA, last Saturday. It was all the fun of the fair, missing only the candyfloss. Redford was planning to hand out his freebie paintings on cardboard to people as they arrived—you get what you’re given! But, instead, he allowed everyone to rummage around and make their own selection. Good call. People were on the hunt for an overlooked masterpiece, a diamond in the rough, exercising their connoisseurship (or bias), perhaps assuming something special in the work might speak to something special in them.

As Redford gave away his works, undermining his market, it was also the first day of Living Patterns—the abstraction show at Queensland Art Gallery curated by Ellie Buttrose—which he was also in. Young artists, in town to give talks in front of their works there, then headed over to pick a free Redford. Later, at a Negroni bar in Fish Lane, their acquisitions were lined up, with the owners debating and defending their selections, discussing whose was best, the merits of gesturalism over constructivism, etcetera.

Like everyone else, I bonded with my personal pick. Redford offered to inscribe the back. Having curated his work in the past, I suggested ‘You complete me.’ He said no. What about ‘You deplete me.’? He said no. Then, spontaneously, he wrote ‘You are the wind beneath my wings.’ Redford at his most charming.

•

Do You Want a Piece of Scott Redford?

On Saturday—the opening day of Queensland Art Gallery’s show Living Patterns: Contemporary Australian Abstraction—pop-punk provocateur Scott Redford will be outside, bringing abstraction to the people.

Redford made his Iso Paintings over several years, including during Covid lockdowns. But now he’s combating isolation, reconnecting with the people, by giving away the lot for free, from 10am on the Gallery of Modern Art forecourt. But only one painting per person—don’t be greedy! And you must agree to be photographed with your new acquisition—quid pro quo! His booth closes at 4pm or when there are no works left—so come early.

While you’re on campus, take the opportunity to see Living Patterns. It includes Redford’s giant work Reinhardt Dammn: Things the Mind Already Knows (2010). This fact frames Redford’s forecourt giveaway stunt—him being at once inside the institution and out, an insider outsider, ever in two minds.

•

Nobody Puts Baby in a Corner

Yesterday, I opened my friend Jacky Redgate’s exhibition Hypnagogia with Mirrors at Wollongong Art Gallery. Curated by the artist, this idiosyncratic show brings together old works, new works, and archival materials, all in conversation with each other and with the shape and history of the building. It’s on until 26 November 2023. This is what I said:

There’s a great moment in the film Casablanca. Fate has brought Rick (Humphrey Bogart) and Ilsa (Ingrid Bergman) together again. Ilsa asks Rick if he recalls the last time they were together, as lovers, that day the German tanks rolled into Paris. ‘I remember every detail’, Rick says. ‘The Germans wore grey, you wore blue.’

I love that line. It says so much about how we all experience the world, combining big world-historical events, which matter to everyone, with small events, which matter just to us and ours. In our own psychic world, mass invasion by fascists can be eclipsed by the hue of a lover’s frock. These things define us.

That scene in Casablanca came back to me when I was talking to Jacky Redgate during the development of this show, we’re opening today.

But first, let me backtrack …

When I first saw Jacky’s work, in the 1980s, I was drawn by its seriousness. Her stunning photographic series Photographer Unknown, Naar Het Schilder-Boeck, and Work-to-Rule seemed cool, conceptual, and calculated, elegant and erudite. They didn’t seem autobiographical or personal. They seemed to speak to a wider-world concerns, to histories, to theories, to ideas. I was seduced by their smarts. In 1991, I organised an exhibition of her work for New Zealand, which emphasised this understanding.

But, years later, I became aware of another side of her practice, insistently biographical and personal, focused on childhood memories, even touching on a childhood trauma. When she was three, Jacky took a turn and was hospitalised. Her mother recorded her delirious utterances in a diary. These comments became the subject of a series of surreal photographic tableaux. This series looked back to early Jacky works with psychosexual overtones—her 1970s juvenilia—that one might otherwise have assumed she had transcended.

In 2008, I made another show with Jacky at the Institute of Modern Art, Brisbane. Visions from Her Bed included some of the personal stuff, including a creepy early photo of Jacky curled up in a baby’s cot wearing a pig’s-head mask and shiny leggings. The show raised the question of how this personal dimension might have informed Jacky’s later, largely impersonal work. Its title prompted us to imagine all her work as if viewed from the hospital bed of her childhood convalescence.

In 2020, adult and baby Jackys collided spectacularly in Hold On, a photographic series made for Geelong Art Gallery. Jacky’s serious, high modernist abstractions were rudely overrun with dolls and teddy bears, playing doctors and nurses, among other things. Were these new-naughty, kitschy-kiddy works calculated to offend those who loved—and had invested in—adult Jacky? (I think of Guston disappointing his fans, when he unveiled his comic figurative paintings at the Marlborough Gallery in 1970.)

In Hypnagogia with Mirrors, Jacky has curated herself. The show includes familiar work, previously unseen work, and new work. Her childhood story is referenced in works, but also in archives. The show encompasses Jacky’s life and work, adult and baby, the impersonal and the personal, systems and symptoms—all talking to or past one another, asking us to make sense of them.

Jacky has organised these aspects of her work and life—in all their contradiction—into the symmetrical crown structure of the Wollongong Art Gallery. Things on either side mirror one another, as if pointing to similarities and differences.

To me, it seems, her curatorial process was as much about how to pack a mental suitcase as how to tell a story. It’s as if Jacky is inviting us to rummage through the hemispheres of her brain, where the contents and where they are filed might both be important. Hypnagogia with Mirrors seems to be full of coincidences, juxtapositions, and eureka moments. But is it significance or serendipity? Your call.

The Germans wore grey, you wore blue.

[IMAGE: Jacky Redgate Wedding Wishes 1977]

•

Always Take the Weather with You

I’ve just arrived in sweaty Brisbane from windy Wellington, and my internal thermostat can’t cope with the heat and humidity. Staggering through the sculpture garden at Queensland Art Gallery, I encounter a work that speaks to my situation—perhaps ridicules it. A glass-fronted freezer contains a bulbous snowman with a quizzical expression.

Snowman (1987–2019)—by Swiss artists Fischli and Weiss—is a deft gesture that can be endlessly unpacked, this way and that. I can confront it as alien or identify. Is it dead or alive—or, like Schrödinger’s cat, both at once? Is it in cryogenic suspension? Is it wise and kind, like Buddha (a Bodhi tree is planted nearby), or moronic and demonic?

The Snowman may occupy its own insulated realm, a world apart, and yet Queensland Art Gallery, just metres away, is also a big glazed refrigerator, chilled for the comfort and preservation of people and things. Is the work thumbing its nose at climate change or reminding us that the gallery—indeed, the entire city—is an expensive airconditioner.

Queensland’s Snowman is one of three. The first is installed outside Germany’s Römerbrücke power plant, whose heat keeps it cool. Another belongs to the Museum of Modern Art, New York. Queensland’s was acquired for the exhibition Water in 2019, where it was installed inside. But I find it more poignant, more funny, outside in the sculpture garden. In a place designed to view sculptures in the round under changing climate conditions, it’s a picture frozen in a frame.

In the wretched heat, I fantasise about trading places with the snowman—watching people and seasons pass, chilling out, with a self-satisfied grin.

[IMAGE: Fischli and Weiss Snowman 1987–2019]

•

When You Sell Me

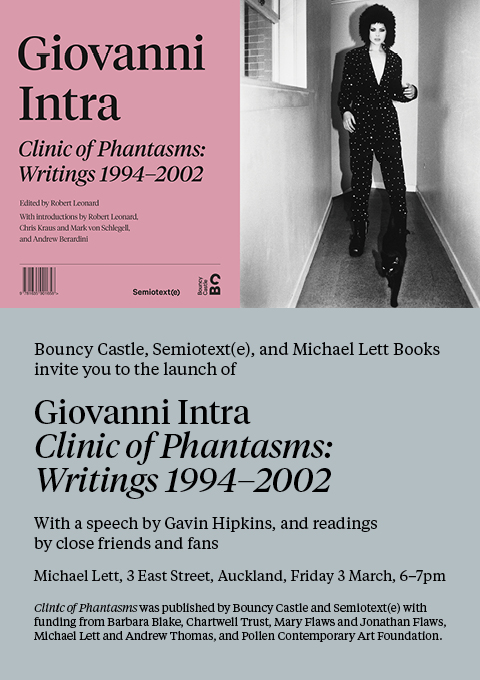

Yesterday, I was in Tāmaki Makaurau Auckland for the New Zealand launch of Clinic of Phantasms, Giovanni Intra’s collected writings, at Michael Lett’s bookshop. I edited the collection, it was published jointly by my imprint Bouncy Castle and by the venerable LA imprint Semiotext(e), and it was years in the making. The room was full of Intra’s friends and fans. Gavin Hipkins gave a speech, and Kirsty Cameron, Jon Bywater, Ann Shelton, and I read from Intra’s texts.

When I assembled the collection, I was advised to exclude Intra’s juvenilia—when he was ‘finding his voice’—so I left out everything before 1994. The text I chose to read from, ‘When You Sell Me’, wasn’t included in the book. It was written for Stamp in 1990. Pretentious but prescient, it shows the writer Intra was becoming. Here’s the excerpt:

I tingle with joy because I know all my enemies will be pissed off for days and I will glow like jelly and it is all because of you.

If you choose me I will honour you by chopping off my ear, spitting across the gallery at you, and being a real anarchist.

I like the space, you like the space, it’s a good space, it would look good in outer space, if I was you I’d send it into outer space.

You insure everything beyond its value, so that, if it blew up, you would be better off anyway.

I can’t touch it, they can’t see it, she can’t afford it, they want to buy it, you can’t touch this.

We used to spend hours looking at encyclopedias and history books, and now we spend hours looking at vital health statistics and pumping cholesterol from our lungs.

At the opening I wore my tweed coat, my polka dot tie, my green trousers, my armour plated knickers, and I painted my nose red.

The artist rejects symbolism and borrowing from indigenous cultures, rather he attempts, through a process of reduction and distillation, to penetrate a common level of collective consciousness.

We know our positions too well. There is enough measured contempt and praise to keep our frustrations and pleasures balanced for a lifetime.

I’ll do the mail-out, you do the mail-out, she got sent a mail-out, he’s on the mail-out list, let’s hope the mail gets lost in the mail.

I fuck you and spit at you, you ruin me, you sell me, and this is the best art there ever is.

Everything would be totally different if the opportunity to sell out actually existed.

Thanks to Michael Lett, Andrew Thomas, Victoria Wynne-Jones, and Samuel Holloway for hosting the launch and to everyone who came. Copies of the book are available at Michael Lett’s bookshop, and soon at better bookstores everywhere.

•

Day One

I have a new job. In fact, it’s an old job. I’m returning to my former position as Director of the Institute of Modern Art in Brisbane. I’m excited to be back in Queensland and look forward to embarking on a new chapter for the Institute and myself. Thanks to the Board for this wonderful opportunity. I start Monday.

•

Sous les Pavés, la Plage!

The revolution is earnest, serious stuff. But what happens when revolution and style are scrambled—when art, fashion, and popular culture look to politics for an edge, and when the revolution needs a look to advertise itself? I’m giving a talk about my 2018 City Gallery Wellington show Iconography of Revolt, which tracked the absorption of edgy revolutionary imagery and strategies into the mainstream. I’ll be reflecting on the implications for art and curating. The talk will take in Bolshevik sportswear and Black Panther propaganda, hacktivists and hijackers, stone throwers and balaclava wearers, Pussy Riot and the Ayatollah, Maoists in a Paris flat and a flower-power orgy in Death Valley, terrorists on the catwalk and university-recruiting videos. Come along. Saturday 3 December 2022, at 4pm, at Starkwhite Queenstown, 1–7 Earl Street. It’s part of the Curious programme of talks and events in Queenstown organised by my friend Kelly Carmichael.

•

Stars Align

As fate would have it, I have curated three shows that are all open right now. Tia Ranginui: Gonville Gothic at Te Uru, Titirangi, a tweaked version of our 2020 show at City Gallery Wellington (until 26 February 2023); Lucien Rizos: Everything, at the Adam Art Gallery, Wellington (until 18 December); and Divergent: New Photography Aotearoa with Ranginui, Telly Tuita, and Cao Xun, at The Renshaws, Brisbane (until 8 December). There has already been some coverage. John Hurrell reviewed Gonville Gothic for EyeContact here; Eva Corlett previewed Everything in the Guardian here, Thomasin Sleigh reviewed it in the Dominion Post here, and Kim Hill interviewed Rizos on RNZ here; and Hamish Sawyer profiled Divergent for Lemonade here.

[IMAGE: Cao Xun Butts Up 2020]

•

One Mind

Come and see my new show, It’s Personal, presenting the New Zealand photography collection of former ad man Howard Greive and photographer Gabrielle McKone. The Wellington couple began collecting New Zealand art in the 1980s, but fifteen years ago they decided to focus exclusively on photography. Greive says, ‘Maybe it’s years in advertising but a sharp, single-minded proposition always works. And, for us, that SMP was photography.’ Their place is packed to the gills with photographs ranging from expressive to conceptual, documentary to directorial, but they don’t spread their bets, preferring to collect key figures in depth. The show features works by Edith Amituanai, Janet Bayly, L. Budd, Joyce Campbell, Gavin Hipkins, Jae Hoon Lee, Anne Noble, Peter Peryer, and Yvonne Todd. There’s also a cluster of gems from earlier figures: Theo Schoon, Ans Westra, and Gary Baigent. Join us for the opening preview, Tuesday 9 August at 6pm; and for the closing-day talk, on Sunday 21 August at 11am, presented in conjunction with Photobook/NZ. It’s Personal: The Howard Greive and Gabrielle McKone Photography Collection, Webb’s Wellington, eleven days only, 10–21 August 2022.

[IMAGE: Yvonne Todd Wet Sock 2005]

•