When I’m in Paris—which isn’t often—I like to go to the Musée d’Art Moderne de la Ville de Paris to see one of my favourite pictures: Kees van Dongen’s The Sphinx (1920). It’s not the greatest painting, but the attitude it captures … priceless. Dutch-born, Paris-based, Van Dongen was a fauve. Early on, he painted good-time girls, prostitutes and dancers, florid and flirty, in ripe colours, with big eyes. Later, he became a high-society portraitist, celebrating classy ladies in chilly whites and silvery greys. The Sphinx belongs to this later phase, although I haven’t been able to find anything about the sitter, Renée Maha. When I first saw The Sphinx, it disarmed me. Hands come in from stage left offering a vase of chrysanthemums, only to be greeted with a chilly ‘unamused’ glare from the languid, elongated sitter. Sure, there’s a misogynist element here. The Sphinx was a merciless mythic being with the face of a woman, the body of a lion, and the wings of an eagle, who would kill you and eat you if you couldn’t answer her riddle, solve her enigma. The painting is also a classic example of metonymy. That vase of flowers is like the painting itself, being offered to the ice queen by Van Dongen as the painter-supplicant, seeking her approval. Instead of solving her riddle, he simply reflects it.

•

Zinger

My favourite mean opening for a mean review: ‘One thing you can say for Buzz Spector is that he does his homework. The bummer is he hangs it in galleries and calls it art.’ Lane Relyea, Artforum, May 1992. Can it get any worse?

•

Preppers

I recently dropped in to London’s National Gallery, where a new acquisition—Abraham Bloemaert’s Lot and His Daughters (1624)—was proudly on display. The label was telling: ‘Genesis recounts how Lot and his family fled the destruction of Sodom, with Lot’s wife turning into a pillar of salt on looking back to the city, seen in the background of this painting. The main scene—a triangle of primary colours—shows Lot’s daughters, believing only they remained alive on earth, taking the desperate measure of seducing their own father in order to perpetuate the human race.’ And there they are, in the artist’s imagination, plying their tired papa with booze, oysters, themselves. Only in the movies.

•

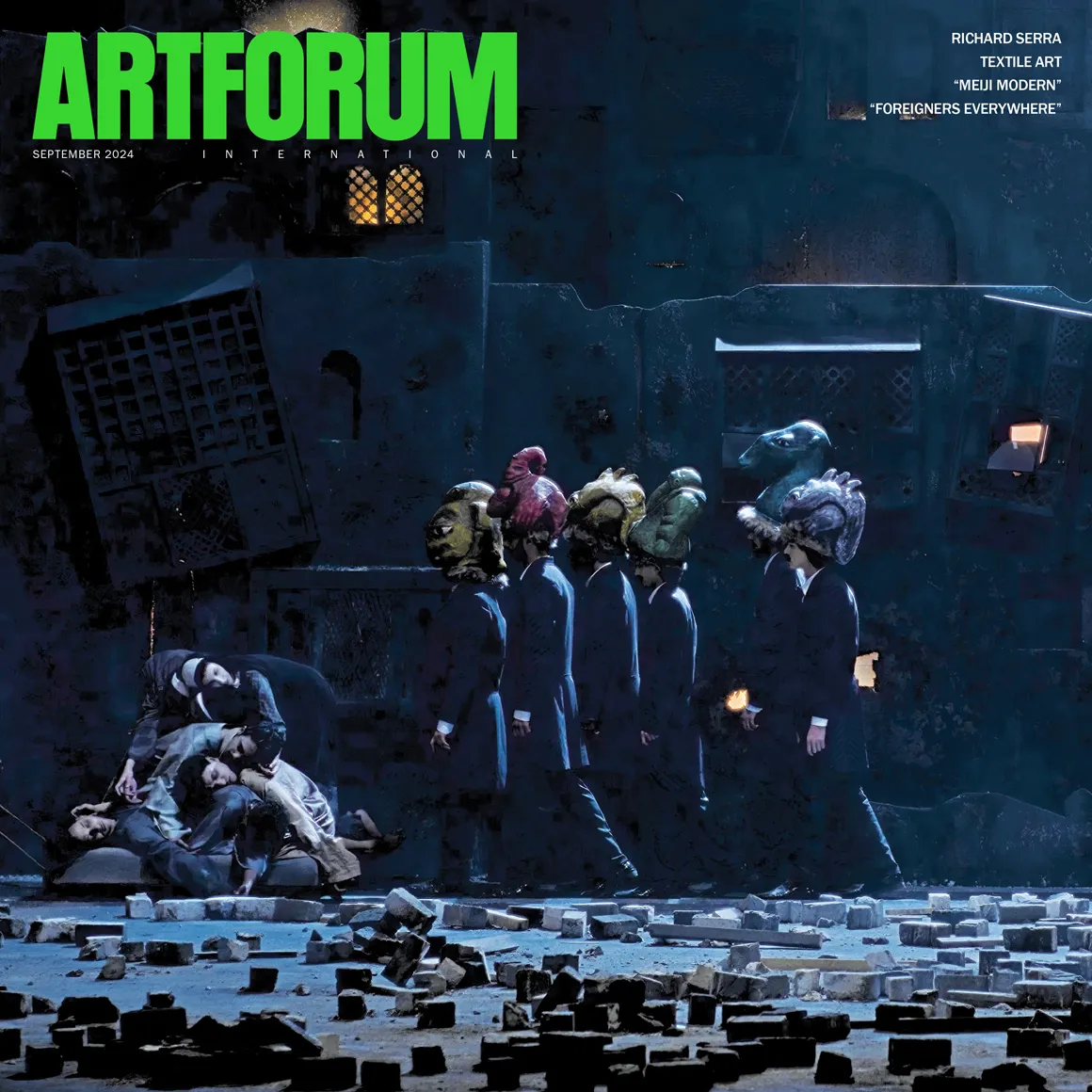

The Grail

When I began reading Artforum—in the early 1980s, on deskcopy at Elam art school—the idea that New Zealand would one day figure in its pages seemed inconceivable. New York was the centre, New Zealand the periphery; New York was Broadway, New Zealand was off-off-off Broadway. In 1992, Julian Dashper would address this in a project in Artforum. Feeling excluded, he bought advertising space to make a page project, where he fantasised, first, being on the magazine’s cover, and, then, in its reviews pages. Later, Dashper would be instrumental in bringing (now-disgraced) Artforum publisher and advertising man Knight Landesman to New Zealand and things started to turn. With this contact and, crucially, with a global turn in the art world, we began to see more New Zealand content, with Anthony Byrt becoming a regular writer. Nevertheless, I was surprised to open the latest issue of the magazine to find New Zealand suddenly permeating it. There’s a double-page spread reproducing Richard Serra’s Te Tuhirangi Contour at Gibbs Farm, and another of Mataahou’s Takapau, Golden Lion winner, kicking off the Venice-response section. There’s a feature on Christoph Büchel by Simon Denny, a review of Dan Arps in Whangarei by Anthony Byrt, and an interview with Vera Mey, co-curator of the Busan Biennale. All this coverage is there as a matter of course, not as the result of any special prompting or pleading. It’s exciting, but also deflating. It’s like discovering the holy grail, only to realise the quest is over. We can no longer aspire to join a club that won’t have us as a member.

•

The Years Have not Been Kind

Ken Downie took this photo of me around 1987. He photographed everyone in his circle in Wellington as if we were worthy of the David Bailey Box of Pin-Ups treatment—as if photographing us like stars might make us stars. It’s weird viewing this image of myself looking so sensitive and thoughtful (when I wasn’t), unlike now (when I am).

•

Thank Christ

Here’s a view of our latest exhibition at the Institute of Modern Art, Duty of Care: Part One. It shows a controversial United Colors of Benneton ad from 1992, reproduced billboard scale. (I’m old, so I remember how edgy the ad was when it first came out.) Here, it’s accompanied by Michael Parekowhai’s 1994 sculpture Acts II on loan from Queensland Art Gallery. Its title refers to the The Acts of the Apostles from the Bible.

Benneton is an Italian knitwear brand. In the 1990s, it courted controversy with its polarising ad campaigns drawing on hot-button political issues. Its art director Oliviero Toscani often made his ads using found press images, never showing the product. By aligning itself with urgent social issues and humanitarian crises, the brand pioneered corporate virtue signalling, but also opened itself up to criticism for exploiting pain and suffering to sell sweaters. Many publications chose not to run the ads. At the time, the Benetton campaigns were widely discussed in the art world; they were part of the art discussion.

This particular ad shows a Christ-like David Kirby dying from AIDS in Ohio. It is a classic care image, showing parents tending to their dying son. The photographer and the family agreed to let Benetton use the image, to raise AIDS awareness. The original photo was in black and white, but has been coloured to give it a nostalgic, Catholic-kitsch feel. The scene recalls images of the deposition, the pieta—Christ with mourners. In a painting in the background, we can see caring Christ-like hands reaching down over the scene.

It’s a reminder of how much Christianity informs Western ideas of care.

•

Another Day, Another Book Launch

Join us.

•

Black Mirror

Doreen Chapman’s paintings of ATM machines are one of the hits of the current Sydney Biennale; they have people talking. They are prominently installed at the entrances of each of the Biennale’s venues, where actual ATMs might once plausibly have been located, as if standing in for them. One scours the Biennale’s wall texts and catalogue in vain for clues of the artist’s purposes in making them or the curators’ purposes in including and positioning them. They remain a curious presence.

Born at Jigalong Mission in the early 1970s, Chapman primarily lives in Warralong Community and paints at Spinafex Hill Studios and Martwill Artists. Her naïve-style paintings often feature landscapes, flora and fauna, cars and aeroplanes, but ATM machines are a new subject for her. Chapman is deaf and non-verbal, and, as much as we may ponder the new works’ significance for her, she’s not telling.

Chapman’s ATM paintings are a mixed bag. Where they feature the acronym ‘ATM’ or a bank logo, the subject is clear. Where they don’t, we would be pushed to recognise the subject, without being told. The paintings have different characters. One, with chubby numerals, reminds me of Claes Oldenberg’s soft sculpture; another is more Rothkoesque.

It’s odd to see abstracted frontal views of ATMs where one might expect to find abstracted aerial views of landscapes. I imagine a gallery guide standing in front of them explaining how money works and what a PIN is, where they might otherwise be telling tales of Country.

The Biennale wall texts describe the paintings as depictions of contemporary Indigenous life. For the urbanised Biennale audience, in the EFTPOS epoch, ATMs and cash may feel like things of the just past—most of us have stopped using them. However, in remote communities, where many are poor, isolated from the internet, and live on benefits, ATMs play a big and central role. They can be few and far between and can run out of money.

I find it disorienting to see these ubiquitous, banal forms from my own culture—the mundane machinery of money—explored as mythic-poetic objects, oddly mirroring the way we are drawn to expressions of other cultures as enigmatic.

•

Sprezzatura

Gemma Smith’s show at Brisbane’s Milani Gallery is a breath of fresh air. At a time when our galleries are laden with issues and identity—and nothing makes sense without consulting the wall text—Smith’s immediate, joyous, eye-candy abstraction comes across as a guilty pleasure.

The Sydney artist’s work may be easy on the eye, but it’s smart. At first, I couldn’t work out how the paintings were made. I thought she may have used masking to generate the shapes. Not so. Actually, she brushes on a thin veil of colour, then shapes it by wiping off excess paint with a cloth. Then another veil is overlaid and shaped. And so on. Smith’s wipes generate arcs. The resulting forms are transparent—hard edged, yet soft and brushy.

In these paintings, everything is busy, yet light and lightness prevail. It’s all contrast and counterpoint. Paint is applied in one direction, then removed in another. There’s the movement (and implied speed) of the application, the movement (and implied speed) of the removal. Plus, there’s the optical drama built up from the interactions of lines and colours. Each work has its own distinct architecture and personality.

These are big paintings, produced up close but to be viewed from a distance. Smith’s ability to keep everything under some control while improvising at the coalface is impressive. She reconciles the geometric and the gestural—drawing and painting—in a new way. Gemma Smith: Orbits, at Milani Gallery, until 27 April.

[IMAGE: Gemma Smith Infinitely 2023]

•

Our Third Book

Bouncy Castle’s third book, out in the New Year.

•