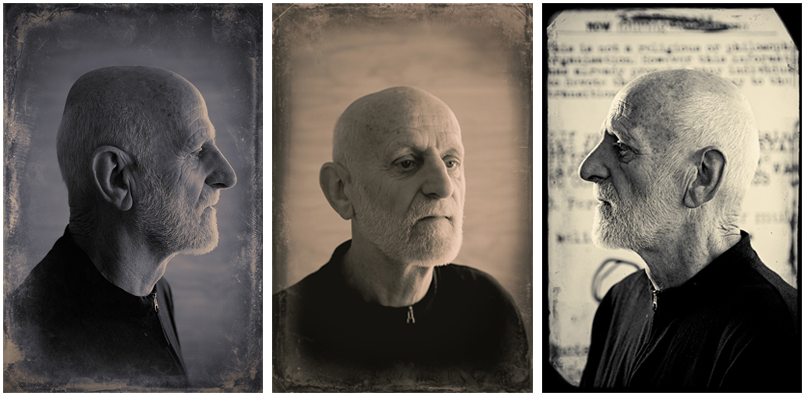

Luit Bieringa died this week. He was a big figure in my life. In 1985, when he was Director of the National Art Gallery, he gave the kid a break, appointing me as the Gallery’s first curatorial intern. Back then, I was a feral mess, unsuited to institutional life, however, against advice, he tolerated me, supported me, sheltered me, parented me. After my internship, he gave me a job as curator of contemporary New Zealand art. It set me on my life’s course. I can’t imagine where I would have been otherwise.

Bieringa was an art missionary, working at the coal face, taking art to the disbelievers. In 1971, he started off as the director of a small regional space, the Manawatu Art Gallery in Palmerston North. When he arrived, it was in a house; when he left, it was in a new purpose-built museum. While he was there, he mounted important shows of McCahon and Woollaston (the subjects of his master’s art-history thesis, New Zealand’s first) and The Active Eye (a survey of New Zealand photography). He had a can-do attitude. He was limited by time and money, but never by lack of vision.

In 1979, Bieringa was given the reins at Wellington’s National Art Gallery and blew the dust off. He professionalised things: building up the staff and facilities, growing the collection and mounting impressive shows. He gave the old NAG a contemporary edge and relevance. By the time I arrived, the place had real momentum. It felt like a sandpit full of toys. And that was my introduction to curating.

In 1986, when Bieringa’s plans to develop a new National Art Gallery were thwarted, he created Shed 11, a contemporary-art annex on the waterfront, and presented audacious shows like Wild Visionary Spectral: New German Art, Content/Context, Barbara Kruger, and Cindy Sherman.

But, in 1989, after ten years, Bieringa’s directorship hit a wall. He found himself at loggerheads with the Museum of New Zealand project—which he had inadvertently kick started. It had developed a life of its own, and was out to kill its maker. Now an impediment, Bieringa was dismissed. Unfairly, said the judge. In 1992, Shed 11 was closed. It was the end of the golden weather. The city lost not only a physical space for showing art, but also a symbolic space for speculation. Luckily, Wellington City Art Gallery would pick up the slack.

Beiringa dusted himself off. He stayed in Wellington. He went on to do important exhibition and publishing projects as a freelancer, and with wife Jan reinvented himself as a filmmaker, making insightful documentaries on Ans Westra, Peter McLeavey, Gordon Tovey, and, most recently, Theo Schoon. But I often wonder what he might have achieved—what we all might have achieved—if he had continued as a museum director, if he had retained that leverage.

I’ve really got to know Bieringa again properly only in the last year or so. We’ve been working together on a book project about Shed 11, which has been a walk down memory lane. It has reminded me what a vital art scene Wellington had in the late 1980s, when the National Art Gallery and Wellington City Art Gallery were both expanding and egging each another on, and new art ideas were fermenting. I don’t think it would have happened without Bieringa. It wasn’t just what he did, it’s what he enabled others to do. He was a catalyst.

•