Yvonne Todd: Creamy Psychology (Wellington: Victoria University Press, 2014).

Something strange is happening in the town of Stepford.

Where the men spend their nights doing something secret.

And every woman acts like every man’s dream of the ‘perfect’ wife.

—The Stepford Wives (1975)1

.

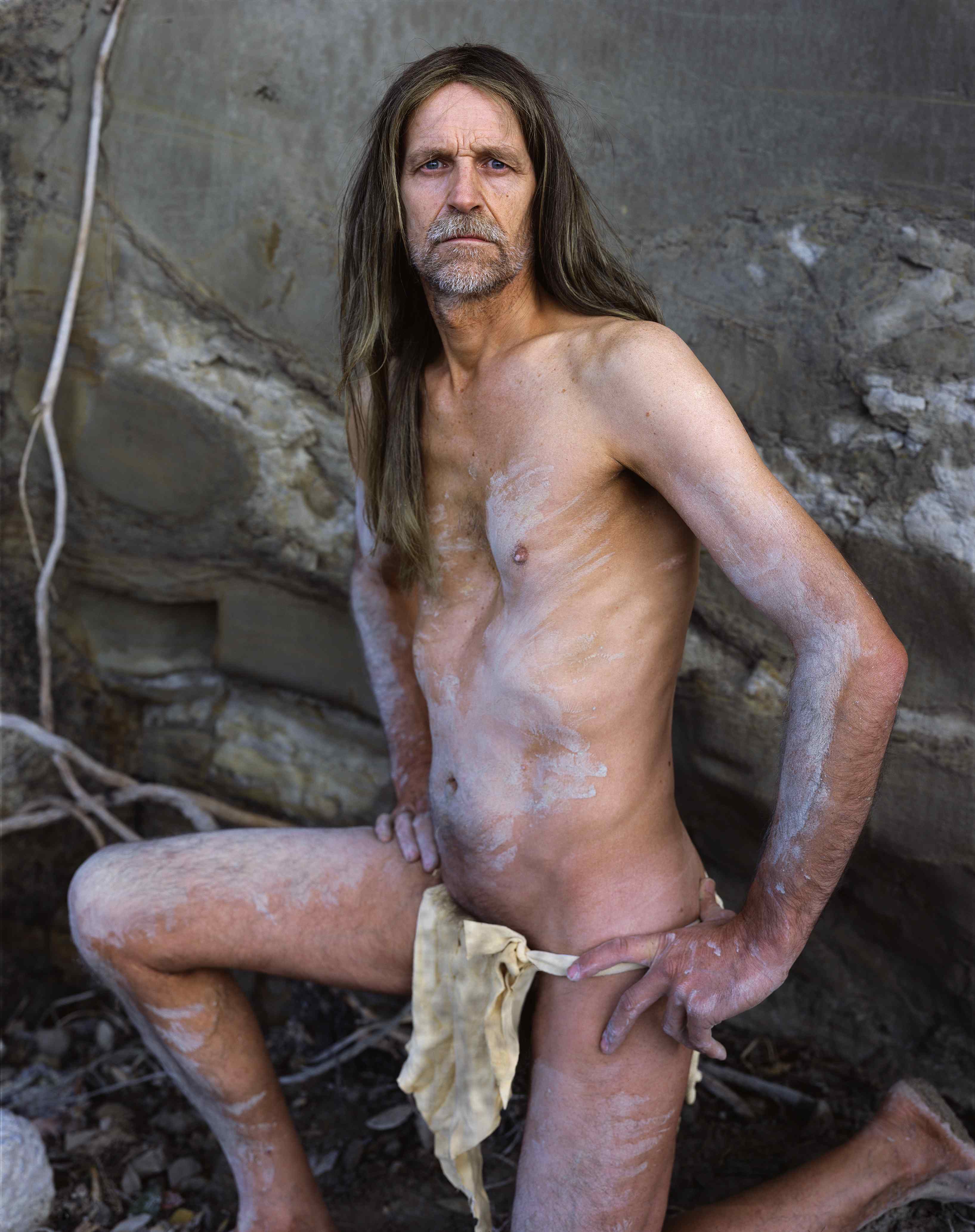

The Yvonne Todd literature is veined with references to cults. Todd and her commentators constantly drop the C-word, yet there are no explicit references to extremist religious groups in the work. There may be vague intimations of cultishness in a handful of images, say in the feral hair and hippie loincloth of Gunther (2010), in the space robes in Gynecology (2006), and in hints of ritual self-and-animal sacrifice in Roba (2004) and Goat Sluice (2006). However, cultishness pervades Todd’s entire oeuvre, including works which contain no such references.

Cults are groups of people who see things in a different way. They are communities within the community, at odds with it. Cults don’t call themselves cults, others do—it’s a term of derision and division. They are defined less by their irrationality than by their deviance, their departure from the common sense.2 A shared faith binds their members, while estranging them from society at large—any ‘us’ needs a ‘them’. And yet the mainstream has much in common with cults. Indeed, each has the same problem with the other—brainwashing. And the same response—deprogramming (or reprogramming).

Todd grew up in the 1970s, the heyday of cults. Christian sects, alternative religions, and counterculture lifestyles flourished. In 1974, the Kirk Labour government established the Ohu Scheme, encouraging rural kibbutz-style communes in the country (possibly as a way of encouraging freaks to leave the cities). Our most famous commune was Centrepoint, a ‘spiritual growth community’, just up the road from the Todds in semi-rural Albany, on Auckland’s North Shore. Bert Potter, a former vacuum-cleaner salesman, set it up in 1977. There, he sat in his peacock chair and railed against repression, guilt, and monogamy, and perfected his own brand of encounter-group psychotherapy. Like many other utopian communities, Centrepoint failed. In the early 1990s, Potter was put away, first for drugs, then for sex with minors. It would be another example of a familiar pattern.3

Back in the day, Todd had nothing to do with Centrepoint, or any cult, commune, or sect. She had an orthodox upbringing (her parents were accountants). But, because of this, the idea of cult life could animate her fantasies in ways that direct experience could not. She admits as much. She says her work Gunther was inspired by ‘memories of a commune in the Kaipara district near my uncle and aunt’s farm. I never went there but heard the stories from my cousins. The commune encouraged a casual atmosphere where nudism was practised. One of the mothers was often naked, sunbathing on a banana lounger, her overgrown pubic area a topic of lengthy discussion among my cousins and me. Instead of consuming lollies and biscuits like normal kids, the children of the commune ate handfuls of savoury yeast from large jars and had odd names like Shanu and Cyrus. We embellished their parents’ nudity to high levels of perversity, although the boring truth was that they were gentle hippies, self-sufficient, working the land, making feijoa wine.’4

Todd’s art is informed by things drawn from her environment, her background, particularly from the novels, TV shows, movies, and other cultural influences she absorbed in her formative years. Her oeuvre offers a mind-map to those talismanic reference points. As she adds works, integrating and cross-referencing new subjects, ‘the world of Yvonne Todd’ expands, old works informing how we read new ones, new works prompting us to reread old ones.

Todd’s world may be unified by her distinctive sensibility, but it also encompasses things that don’t usually get together on the same page.5 Its canon incorporates buck-toothed ugly ducklings (Feast of Phyllis, 2007) and swans (the tragi-glamorous Amanda, 2006), oversexed showgirls (Klerma, 2008) and dowdy Christians (Rashulon, 2007), primped page-three girls (Did Anybody Tell You That You’re Pretty when You’re Angry?, 2010) and grimy hippie dropouts (Gunther). As facets of her world, all Todd’s subjects are somehow interchangeable—stand-ins for one another.

For each of us, some aspects of Todd’s world will be familiar, others inexplicable. Todd’s work plays on how much and how little her world has in common with ours, where it meets ours and where it sheers off. Viewers will vacillate between feeling like members of her cult of sensibility (where it all makes sense) to being tourists in it (where it remains mysterious, exotic, opaque).

Essentially, Todd’s exhibitions take two forms. She makes portrait series, with examples of similar sitters presented in a similar format, like the cosmeticians in Bellevue (2002), the corporate executives in The Wall of Man (2009), and the dancers in Seahorsel (2012). These works survey the members of groups, suggesting communities of like minds. She also makes ensembles of diverse subjects (like The Book of Martha, 2003, and 11 Colour Plates, 2004). The subjects can include portraits, landscapes and still lifes (or, if you prefer a cinematic analogy, characters, location, and props). While images might seem unrelated, the ensembles’ effect is just as cultic as the series’. By presenting diverse images together, framing them under a suggestive title, Todd asks us to imagine that some hidden narrative, some occult knowledge, defines their otherwise inexplicable coincidence.

Even within the portrait series, there is a play between insiders and outsiders. Todd has said that Sea of Tranquility (2002) was inspired by the idea of Mormon pastors’ daughters. However, only three of the five portraits exemplify this idea. The soap-operatic beauty Alice Bayke and the turtle-necked Rebecca Weston don’t fit. Similarly, while the girls in Vagrants’ Reception Centre mostly wear prim Victorian dresses, Mordene and Ethlyn stand out in their contemporary garb. And, while all the other portraits are half length, Ethlyn is full length and plays a guitar. What’s more, all of the Vagrants’ images are inexplicably different sizes—bespoke. Underpinning this play of difference-within-the-same is an idea about individuals and groups—about the way people and things approach and deviate from a norm, and the way we read or intuit such conformity and dissension. Todd prompts us to compare and contrast, and to judge, seeking out heretics and orphans lurking within the club. She makes us discriminate.

Paradoxically, it is with the relatively homogeneous series that we become alert to differences, while, with the heterogeneous ensembles, we suppress them, looking for common ground.

.

Todd’s work may cite elements of mass-media ‘pop’ culture, but she is little concerned with what is truly popular in it. Her references are obscure. Who would have known that January (2006) is based on a heroine in a Jacqueline Susann novel, that Approximation of Tricia Martin (2007) refers to a Sweet Valley High character, and that Joan Kroc (2006) is a nod to the McDonald’s heiress?

Todd is a fan. Fans often pick out and champion peculiar, neglected figures and moments. Such singular, perverse attachments distinguish fans from the hoi polloi. Todd’s work exemplifies the way we cherry-pick from and edit mainstream messages to construct our own highly specified fantasy worlds and identities, transforming the Symbolic (normative images from the Big Other) into the Imaginary (our own thing).6

Such fringe enthusiasms are routinely called ‘cult’. TV shows, of passionate fans while leaving the majority cold. Indeed, the uninterest of others fuels cultic commitments and confirms fans’ suspicion that something special in their favourite things speaks to something special in them. Crucially, there are no solitary cults. To be cultic, obsessions must be shared; they must generate communities of like minds.

The Internet, with its global narrowcasting, has certainly enabled cultishness. Fetishists, perverts and other obsessives who previously feared they were one of a kind can finally find one another. A few years ago, I asked Todd if she saw a link between her work and pornography. She replied: ‘Not with the obvious X-rated kind, but perhaps the more obscure, specialised and, to the non-aficionado, quite boring, obsessively repetitive stuff: the pornography focusing on mundane tan-coloured pantyhose or matronly brassieres and flesh-tone petticoats.’7 Because of some bent or incident, fetishists invest chunks of the ordinary with an extraordinary allure. Of course, Todd is one of them too, trawling specialist sites on the Internet, seeking vintage frocks to use in her photographs, credit card at the ready.

When I look at Todd’s images, I often think: why has this image been made, and for whom? Who is it addressed to? Putting aside the obvious (that it has been made for us by Todd), it often feels like the work is addressed to a specific viewer with a peculiar interest in the subject or its treatment. Take Frenzy (2006). A big-toothed blonde, dressed in acres of tartan, reclines in a breeze-block basement. The image could be the work of an amateur photographer, making do with a toothy date, an odd dress and an inappropriate location. Or, did the photographer get it exactly how they wanted? Frenzy is at once prim and perverse. The dress is weird, monstrous, looming. You can’t see the girl’s body. Is the sexual centre of interest the girl (her hidden flesh), the dress (the strident tartan), those teeth (why not?), or, indeed, the basement itself?

Although we can’t quite pin it down, Frenzy reeks of someone else’s sexual obsession, and leaves us wondering, first, how their proclivities were formed, and, second, about the model’s complicity in them (or ignorance of them). Art writer Serena Bentley said Frenzy reminded her of the Austrian Josef Fritzl, who, for twenty-four years, imprisoned his daughter Elisabeth in his basement, for his pleasure.8 In the small town of Amstetten, Fritzl maintained appearances. No one suspected what lay beneath. Incidentally, his cover story was that his missing daughter had joined a cult.

Todd plays on the difference between the normative (conservative, prevailing, mainstream values) and the alternative (the subcultural, the cultic), and on the way they mirror one another. Todd commentators routinely namecheck a precedent for this—The Stepford Wives, the 1972 Ira Levin novel and 1975 Bryan Forbes film.9 In a white-bread, white-picket-fence Connecticut suburb, women have become compliant mannequins—puppets. The men have replaced their wives with glamorous, docile, submissive fembots. Stepford is a cult, a secret society, albeit one maintaining appearances more normal than normal, straighter than straight. One is reminded of the cosmeticians in Bellevue, who seem both hyper-conservative and alien. Are they authority figures or victims of their own philosophy?10 Similarly, what would it take for the corporate executives and specialists in The Wall of Man to become charismatic cult leaders? Are they already? These days, every respectable father or father figure is considered a potential abuser. Studio photography is typically used to create positive official images. Todd’s images nag at that expectation.

Todd’s 2011 series Seahorsel also conflates the conservative and the cultic, scrambling the look of a mainstream clothing-catalogue shoot with obscure ‘ritual’ actions involving beachy props (shells, seagulls, seaweed, and sand). The key work, Glue Vira, is an encasement fetishist’s dream. It features two women in flesh-coloured body stockings. A glamorous hyper-feminine blonde, with big hair, is posed like a puppet on a string, or as if hypnotised—pure Stepford. A brunette stands behind her. Fabric hangs limp from the arm of the blonde, while fabric billows on the arm of the brunette, implying motion and agency. It’s hard to know if the brunette is another poseable puppet or the puppet master. There’s a creepy eroticism and beauty to the image.

The idea of becoming a doll is not without its appeal. In Seahorsel, Todd acknowledges that even men might enjoy it. Morton features a Ken-doll-like man, with hunky good looks, straight from central casting. His padded neck brace and bodyhugging shirt look like the body of a soft-toy. Todd’s title refers to Morton Bartlett, the American outsider artist, who was shown alongside her in the 2005 exhibition Mixed-Up Childhood. From 1936 to 1963, Bartlett, an orphan and perennial bachelor, made a family of lifelike plaster dolls (the family he never had) and photographed them. His doll works seem both conservative (happy families) and uncanny, creepy (anatomically correct). It is hard to know if Bartlett was an innocent or a pervert (and perhaps the perviness is something we bring to his works). Either way, Todd’s portrait references Bartlett’s implicit dream, to be somehow at one with his doll family.

Todd is a master of the line call and the flip-flop, with everything on the verge of turning into its opposite. Because of this, her works raise thorny questions about women’s agency. Her oeuvre is full of sad cases, cripples, Miss Lonelyhearts, and other victims of circumstance raised to the state of heroines, worthy of a studio portrait. I believe Christianity is at the root of this, for giving us an image repertoire of suffering martyrs turning the other cheek and receiving grace. Todd lets us wonder whether and to what extent her characters are genuine sufferers denied agency (doormats) or self-indulgent thespians ready for their close-ups. Do her female victims own their masochism or abdicate responsibility, blaming their TVs, lovers, or charismatic cult leaders? Todd doesn’t want us to fall down on either side of this interpretive line, but to see the line and the ways our desires inform our judgements.

.

This comes to the fore in Todd’s latest series, Ethical Minorities (Vegans) (2014). With seventeen images, it is her largest series to date. Todd sourced her subjects through ads in Facebook and in Vegan New Zealand magazine, asking for vegans to front up and be counted. She shot those who responded, plus herself (she is a vegan too). Each sitter volunteered to be photographed as a representative of this diet subculture, this vegetarian subcult.11

Vegans are more irritating than vegetarians. Their contrived special needs can be frustrating: they interminably grill wait staff and compel others to switch restaurants, or opt out of the rituals that bind us as a community. They seem to sanctimoniously flaunt their difference, their ethical status. They may presume superiority, but surely these benign extremists are simply princesses with peas. And, quite likely, it will not stop with food, but will be linked to other peculiar values and over-sensitivities. Being vegan is just the annoying tip of an annoying iceberg.

Why photograph vegans? And what do Todd’s photographs of vegans tell us? Actually, nothing in Todd’s images tells us that her sitters are vegans. That is only revealed by the series title. The work begs the question of whether one can detect a vegan by their look, and whether you deduce anything about them as a group by visually surveying them. Evidently they have nothing in common, bar their invisible veganness, but will that halt our judgement? Todd plays with and against stereotype. Some of her subjects are overtly subcultural, wearing their marginal status with pride (one has tattoos and piercings, one has dreads, one enjoys Lycra, another tie dye). Others seem defiantly normal, deceptively straight. A woman in a blue jumper looks way too wholesome—a generic mum. A young couple seem too squeaky clean, posed perfectly—it’s wrong.

This community-within-the-community is presented for our scrutiny and judgement. Todd coaxes out our prejudices, prompting us to intuit veganness in contradictory qualities. In one case, we might associate it with leanness, in another with tubbiness. We might link it to pierced and tattooed skin and to clear unblemished skin. And so on. Todd prompts us to operate like those Nazis who condemned Jews at the same time for their poverty and their greed, for being vermin and effete, for being apart and cosmopolitan. Perhaps Todd is asking whether vegans are a community at all. And, if they are, whether that status comes from them (her examples all raised their hands to be counted) or is imposed on them by us (as prejudiced viewers). Have they been captured in their innocence or their conspiracy?

In making vegans visible, Todd suggests we think of them as a secret society operating amongst us, hiding, undetected. Are vegans the chosen? Are they food fascists looking down their noses at us, condemning us for our dietary crimes? Or, do we condemn them for their presumption, their oddness? Who is oppressing whom here? Are we in the right, because we have the numbers? Or are they in the right, because they don’t? Who has the high ground, the moral majority or the ethical minority?

In previous works Todd has used herself as a model, usually heavily made-up and/or photoshopped, for instance, in Martha (2003), Self Portrait as Christina Onassis (2005), Self Portrait as the Corpse of Sandra West (2008), and Greasy Harpist (2010). But what does it mean for her to include her unvarnished self here, wearing slovenly tracksuit pants? In including herself among the vegans, is she identifying with them rather than us? Or, is she going undercover as a double agent among her own (to report back to us), continuing her duplicitous shell game on a new level? Todd’s work has always played on the thought of being a member of—or estranged from—a community. But, here she is, framed within a world of her making, and it is still not clear whether she belongs.

.

[IMAGE: Yvonne Todd Gunther 2010]

- From the film’s advertising copy.

- Christianity began as a heretical Jewish cult, at odds with the mainstream, but became a religion. Also, some might argue that Raëlism, with its alien designers, is more plausible than a Christianity premised on a creator god and a virgin birth.

- Austrian actionist artist Otto Muehl, founder and leader of the Friedrichshof Commune, was also locked up for drugs and sex with minors. David Berg (aka Moses David), the leader of the Children of God, pimped out his female disciples to lure men into ‘The Family’—he called it ‘flirty fishing’—and is reputed to have been a paedophile.

- Yvonne Todd, ‘Do I Even Like Photography?’, Yvonne Todd: Creamy Psychology (Wellington: Victoria University Press, 2014), 29–30.

- Todd might be quick to remind us that construction worker Larry Fortensky married Elizabeth Taylor, after they crossed paths at the Betty Ford Clinic.

- This is what happens in subculture, where elements and images from the dominant culture (the mainstream) are appropriated and repurposed in resistance to it. See Dick Hebdige, Subculture: The Meaning of Style (London: Methuen, 1979).

- Quoted in Robert Leonard, ‘Why Beige?’, Dead Starlets Assoc. by Yvonne Todd (Brisbane: Institute of Modern Art, 2007), 61.

- Fritzl’s crimes were discovered in 2008, well after Todd made Frenzy.

- Another precedent is Rosemary’s Baby, the 1967 novel by Ira Levin (again) and 1968 movie by Roman Polanski, with its satanic cult next door.

- While The Stepford Wives presents itself as a feminist critique, its protagonist, is played by textbook beauty Katherine Ross (also remembered as the love interest in The Graduate). As much as the film seeks to critique absurd standards of female beauty and compliance, the filmmakers couldn’t resist undermining their message by casting eye candy in the lead role. They have their critique and eat it too.

- ‘Ethical veganism’ is a vegan subcult. Its followers not only eat a vegan diet they also refrain from and oppose the use of all animal products.