Art and Text, no. 66, 1999. Review, William Kentridge, MACBA, Barcelona, 1999.

Animated-film maker William Kentridge has enjoyed a meteoric rise to fame. Aside from Marlene Dumas, he is the only contemporary South African artist to have gained international ubiquity (his work has appeared at Documenta 10, and recent biennales in Sydney, Havana, Istanbul, Johannesburg). Yet, by his own admission, the work is provincial and illustrative, the subject matter specific, close to home: the legacy of apartheid and the laying to rest of skeletons in closets.

Although troubling, Kentridge’s films are overwhelmingly nostalgic. Predominantly black-and-white, they recall silent movies with their intertitles and old music soundtracks. The imagery is also explicitly antique: old photos or newsreels of smokestack-era industrialism. The smudginess of the drawings suggests the blurring of memory. There’s a sense here that we are somehow stuck in the past, ensnared in unfinished business.

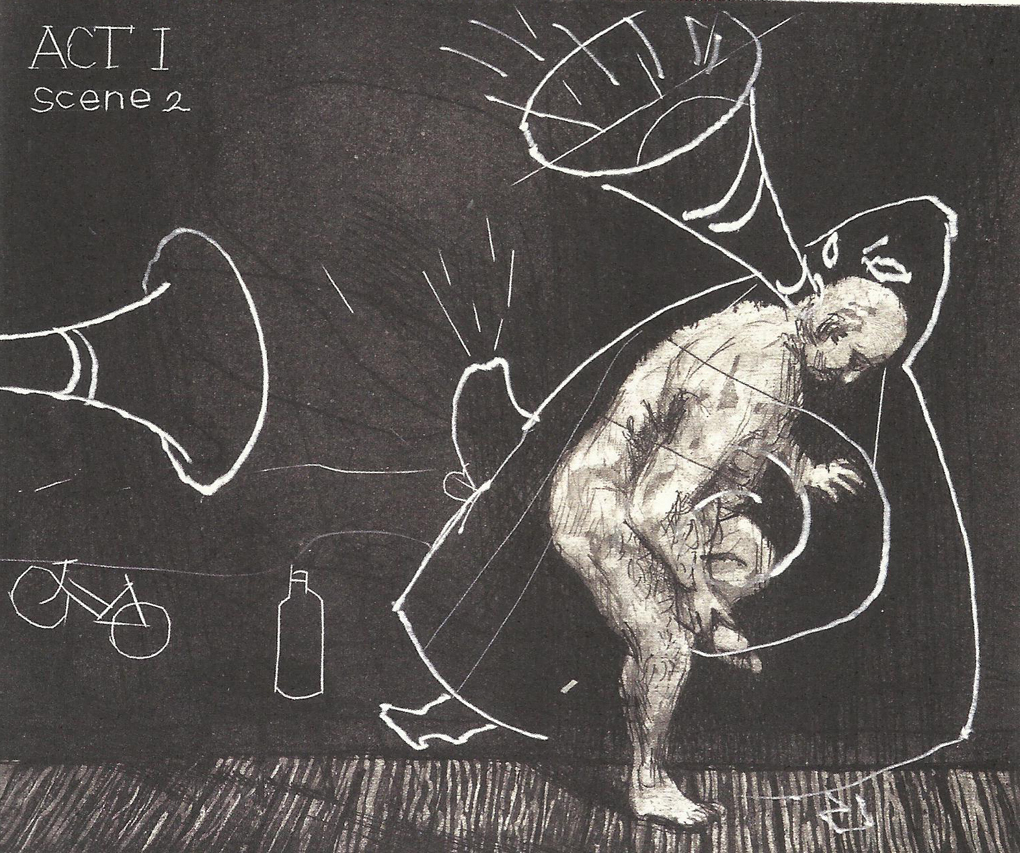

Most of the films rotate around two characters, both white (as is Kentridge). Soho Eckstein is the fat-cat tycoon, creator and ruler of Johannesburg. In his pin-striped suit, puffing on a cigar, he could have been lifted from George Grosz’s caricatures of Weimar bourgeoise. Felix Teitlebaum, whose features are those of the artist, is the artist, the sensual observer ‘whose anxiety flooded half the house’. Lost in romantic possibilities, he hankers after, and makes love to, Mrs. Eckstein. Felix’s struggle against Soho’s evil is played out against the backdrop of the exploitation of the miners and the land.

Soho and Felix are both ‘captives of the city’, but redemption is always a possibility, even for Soho. In Sobriety, Obesity, and Growing Old (1991), Soho outlives his greed to be reunited with his wife, leaving Felix in the wilderness. In The History of the Main Complaint (1996), Soho becomes the object of our sympathy: comatose, hospitalised, and attended by doctor versions of himself, he searches his soul, while his body is probed by a CAT scan. In Ubu Tells the Truth (1997), Kentridge even hints at the possible redemption of Alfred Jarry’s sadistic puppet leader, King Ubu, while, in real life, the Truth and Reconciliation Commission offers amnesty to those willing to come clean and so ‘heal’ the nation.

Kentridge’s animations are created by successively adjusting and re-photographing charcoal drawings. The process has its limitations: the effect is rude, primitive; the charcoal is hard to erase fully and smudges; the drawing betrays the ghosts of its previous stares. But, in the context of Kentridge’s concerns, it is somehow appropriate: his dubious romantic tropes must he employed, as Jacques Derrida put it, ‘under erasure’. There is no storyboard; Kentridge makes the narrative up as he goes along, out of the free associations drawing engenders. Objects are constantly transforming as if to reveal their true colors: a coffee plunger turns into a mine elevator, a cat turns into a telephone. The metaphors are urgent. They move faster than we can read, creating the sense of a world in which the imagination runs amok as compensation for social stasis, for the inability to transform the recalcitrant real world that is the bleak landscape of Johannesburg.

Kentridge writes of his inability to be lyrical, but in his poignant, deeply moving films, lyricism persists alongside, or as a response to, that which would pollute it. The volatile mix of escapism and realism reminds me of Terry Gilliam’s 1985 film Brazil. At the end of that film, the tortured hero finally cracks, escaping, as a sort of compensation, into a blissful utopia in his head. Kentridge’s films aren’t like that, and that’s why he remains a political artist. Lyricism and realism are both present as alternating currents: Kentridge refuses to quash utopian desires while attending to sad realities, and so impels us to seek some resolution in reality. While Adorno wrote that there could be no lyric poetry written after Auschwitz, the ongoing relevance of poetry is the heart of Kentridge’s project.