Photofile, no. 95, 2014.

I had not heard of photographer Viviane Sassen when I chanced upon her Lexicon (2005–11) in last year’s Venice Biennale.1 I came to the work cold and it confused me. The thirty smallish images were shot in a more-or-less documentary style. They looked like they were taken in Africa, or somewhere similar. The series encompasses images of people (mostly black people), places, and things. A man wearing whiter-than-white trainers bears a coffin on his back (Coffin), clothes hang on plants to dry (Laundry), and a dead tree hosts a yellow fungus (Witch’s Butter). Lexicon evokes a familiar tradition—photographers going on safari to record exotic locales and picturesque locals—but it complicates and exceeds it.

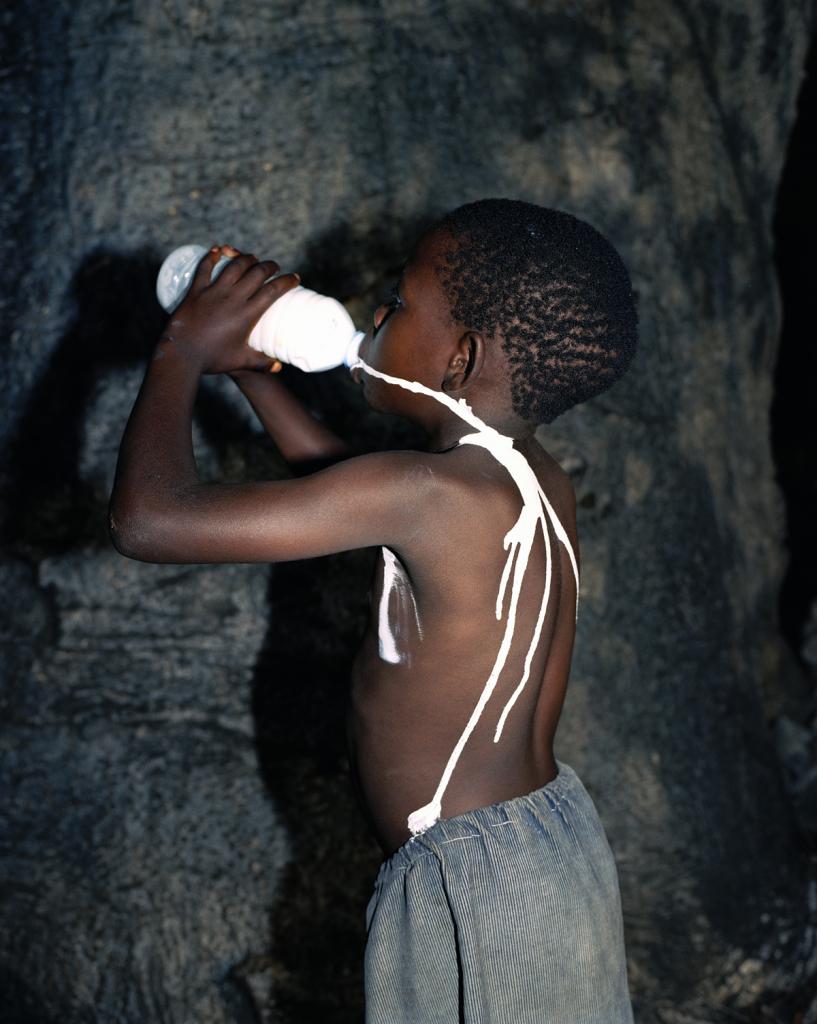

The more I looked at the work, the less simply documentary it felt, in style or ambition. Everything is consummately art-directed. In one tell-tale image (Milk), a boy dribbles white liquid over his black skin, but it is too viscous to be real milk—it looks like special-effects milk. With Lexicon, it is hard to clearly distinguish the aspects that are found from those that are contrived, what belongs to Sassen’s subjects and what she brought to them—in short, what to believe.

Lexicon is puzzling. In so many ways, the images are neither one thing nor the other. The sitters may seem a bit colourfully Third World, but they are also well-dressed and urbane. Despite many references to death and dying, there are no toothless old people; everyone is beautiful—sexy even. The images are redolent with the textures of real lives lived, but also laced with formal conceits and mannerisms. As much as they are a personal response to their subject, they are also a reflection on photography and its tropes. Ambiguity abounds.

In Venice, when I read the wall text, I got the backstory. Sassen is a Dutch fashion photographer, based in Amsterdam. She has worked on assignments for the likes of Diesel, Miu Miu, Stella McCartney and Louis Vuitton, and has published in edgy alternative fashion magazines, including Purple, i-D, Dazed & Confused, Fantastic Man, and POP. For three years, as a small child, she lived in a remote location in Kenya, where her father, a doctor, worked in a polio clinic. It wasn’t until she was five that the family headed back to The Netherlands. Africa—the place of her formative memories—is a home that wasn’t her home. And, so now, she returns there, to make this work.

To me, this explains a lot about the pictures. Sassen is neither a tourist nor a local. She gets up-close-and-personal with her subjects, yet her images remain mysterious, obscure, cryptic. It is hard to see what is going on, to fathom the significance of subjects and gestures. Perhaps this reflects her childhood experience, of being in the fray yet excluded, a white person in a black culture, a child in an adult world, observing without necessarily understanding.

Lexicon has an accumulative, epic structure. While it offers no clear narrative, there are strings of association between images. Lexicon links references to reading, sleeping, dreaming, drowning, and dying. It includes images of sleepers (Belladonna and Saint Louis), of a swimmer with their face submerged (Nungwi), of a man whose identity is concealed and vision thwarted by an open book (Codex), and of a white woman lying in state, with leaves over her eyes and mouth (Inhale). There are also images of body bags, coffins, and graves (Three Kings, Coffin #2, Nadir, and Five Candles). Many of the images were drawn from Sassen’s book Parasomnia, whose title suggests sleeping disorders—the confusion of the everyday and the dream.

The surreal quality of Lexicon is keyed to its subject matter—Africa. Dreams bridge inner and external worlds. They may be in our heads, but they have their roots in unprocessed and disavowed real-world conflicts. We may be the authors of our dreams, yet we experience them as coming from outside us—a cryptic reality to be deciphered. Similarly, Sassen’s work prompts the question of whether (or to what extent) Africa (hers or ours) is an external reality or a projection, a state of mind. She doesn’t answer the question, but lets it hang.

In Sassen’s book Flamboya, Edo Dijksterhuis writes: ‘No part of the world has been so shaped by the images of outsiders as Africa. Images, what’s more, that are full of clichés. Africa, isn’t that mainly starving infants with distended bellies and fat flies swarming around their tear-filled eyes, or burned down huts and severed limbs? Or rather more positively: sun-baked pictures of bone-dry savannas, with elephants and herds of zebras parading before the lens of a National Geographic photographer. At best, the African comes across as a ‘noble savage’, as in Leni Riefenstahl’s highly aesthetic portraits of the Nuba in the Seventies.’2 Africa is a hot potato, an overdetermined nexus of romantic fantasies, racist prejudices, and colonial guilt. But, as much as people generalise about it, it remains huge—culturally and politically diverse. Sassen never specifies where on the continent her individual images come from, but Lexicon does not claim to represent a generic or mythic Africa. It is, in both senses, too partial—it is a personal response and it is overtly incomplete.

For white people, black skin can be a mark of the others’s otherness, their social exclusion. But, for Sassen, raised in a black country, it is the opposite. It is a reminder of her own exclusion. She has said: ‘It’s a more beautiful skin color. When I’m the only white person in a black society, I feel very nude. And when I see other white people in Africa, they’re white, pinkish, ugly and sweating … When I’m in Africa, I feel like I’m coming home, yet I also feel like I’m not one of them.’3

Sassen seems entranced by how black skin appears. In her photographs, black bodies merge into shadows and into one another. Faces coyly emerge from the darkness or retreat into it. Sometimes they become featureless shapes—black holes.4 In photos, black is underexposure—absence of information. In Sassen’s photos, this literal dis-appearance is haunted by problematic metaphors. One of the eternal clichés about Africa is that it is unknowable, incommensurate—the dark continent. At the same time, it is also a convenient screen for our presumptions, including the very fantasy that it is unknowable). Sassen’s shady faces engage such problematic associations. While her images offer hooks to hang our baggage on, the hooks are weak—they aren’t strong enough to hold those ideas. In inviting and resisting our interpretations, Sassen makes us conscious of the limitations of our interpretations.

Asked about her politics, Sassen has said: ‘I’m aware of the whole debate about my depicting black people in Africa as a white European woman, and of me being in control because I’m carrying the camera. But I’m not really interested in that debate, because for me the work comes from a very personal private place.’5 This ‘very personal private place’ is not our place. Sassen’s relation to her subjects is unusual—stemming from her peculiar childhood circumstances. Lexicon is compelling because it communicates something of Sassen’s unique relation to her subjects while also engaging us at the level of our own, more generic cultural predispositions. The framework of her interests and subjectivity locks horns with our own. The work is in two minds.

Sassen’s title is both a key and a red herring. In linguistics, a language consists of two parts: the lexicon and the grammar. The lexicon is the word-stock, while the grammar is the rules by which those words can be arranged into meaningful statements. Both parts constrain what can be said. With her title, Sassen asks us to think of her images as the visual equivalent of words, but lacking a grammar. But, how could these photographs function like words when, as photographs, they are specific, not abstract? Further, if she is tasking us to supply the grammar, into what syntax could we meaningfully arrange these images? In calling the work a lexicon, Sassen frames it as something complete—the full word-stock from which she or we must compose what she or we want to say. But, this suggestion only points to its implausibility—the work’s radically incomplete nature. Indeed, Lexicon is more of an anti-lexicon, with no pretence to abstraction, definitiveness, or universality. Sassen is not summing up Africa. There is no last word.

Sassen has said: ‘I try to make images that confuse me, and I hope they confuse others, too.’6 Sassen frames her audience as much as her subjects.

.

[IMAGE: Viviane Sassen Milk 2006]

- Lexicon is drawn from two bodies of work, each published as books: Flamboya (Rome: Contrasto, 2008) and Parasomnia (Lakewood NJ: Prestel, 2011).

- Edo Dijksterhuis, ‘At the Visual Level of a Whisper’, in Flamboya.

- Tim Murphy, ‘About Face’, New York Times Style Magazine, 8 November 2012.

- In Kinee (2011, not in Lexicon), a model’s black face and hair become a glamorous inky splodge, like a Rorschach blot. Perhaps Sassen is suggesting that, for us, Kinee’s meaning is what we bring to her.

- Tim Murphy, ‘About Face’.

- Viviane Sassen in Aaron Schuman, ‘Viviane Sassen: Parasomnia’, Aperture, no. 206, Spring 2012: 64.