Unpublished.

In the 1970s, society was routinely cast as a conspiracy of repressive forces that shape us and constrain our lives, that suck us dry, that make us pay. In various guises—instrumental rationality, capitalism, the corporation, patriarchy—‘The System’ became the ultimate explanation for all ills. Blaming it for everything, alternative lifestylers ‘dropped out’, preferring—in the words of the Whole Earth Catalogue—to ‘cultivate weeds’.

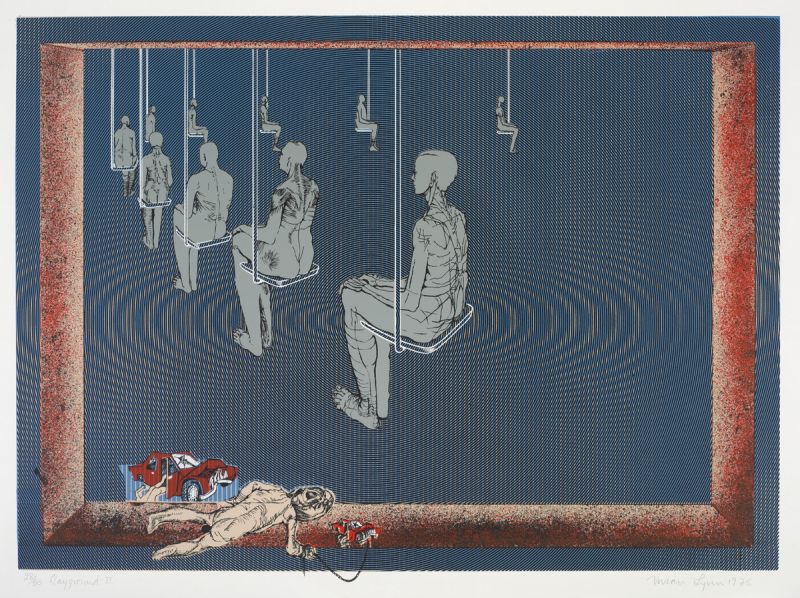

Vivian Lynn’s Playground Series (1975) expresses a classic counterculture-period anxiety about The System. Five of the six screenprints are overrun with naked hairless people—read ‘depersonalised’, read ‘alienated’, read ‘gas chamber’. They play on see-saws, are carried into the void on chairlifts, are stranded high on swings without a safety net, and clamber over a merry-go-round as if it were the raft of the Medusa. Ultimately, they are integrated into smokestack-era industrial machinery, becoming treadmills, flywheels, cogs in the system; although perhaps it looks more like they are being tortured in a medieval dungeon. Lynn’s view is fatalistic: in one image, a prostrate child with a broken toy car is juxtaposed with a wrecked car, implying they are the future instigator or victim of a motor accident.

Playground V has no figures, instead offering an idea of society in the abstract, as a chequered board-game reminiscent of snakes-and-ladders. The snakes and ladders, means of advancement and decline, have been replaced by collaged product images from old ads: canned and packaged peas, meat, baked beans, raisins, TVs, stockings, soft drinks, and a New Zealand–fern logo. Some of the products have been arranged into the shapes of plankton and small deep-sea fish that were then seen as threatened. Around the edges of the board are words, presented like map keys: pay, waste, pollute, expand, wait, advance, progress, consume, stop, buy, penalty, profit, success, interest, consume, loss. Playground V is an allegory of consumer aspirations and their frustration. It is about playing the capitalist game. At the bottom, giant godlike hands—which one commentator identified as ‘big business’, but which Lynn describes as the ‘world manager’—tip the see-saw scales.

The Playground Series is a compendium of classic dystopian motifs: nothing could be less Don Binney. It’s hard to feel sympathetic for its vile, gremlin-like population, which includes infantilised adults and hideous grotesques. The recurrent frame motif, like the frame of a 1970s television screen, boxes in its subjects, enhancing the sense of imprisonment. Sick-making op and moire ‘interference’ pattern backgrounds, made from overlays of Letratone, also recall a television screen, suggesting that ‘the society of the spectacle’ has become a terrifying void, a high-tech miasma. The citizens seem literally ‘lost in space’. The nasty images are presented in a nasty style: Lynn’s tight drawing style is anal, her screenprint aesthetic hygienic, and her colour schemes lurid. She even adds in metallic inks for good measure: granting her prison a special-effects sparkle. Is there an element of schadenfreude here? Is Lynn is diagnosing social ills on behalf of the populace, or is she satirising Joe Average in his apathy and blindness, getting what he deserves?

Lynn has long been interested in making toxic images as a reply to reassuring normative images of society, as if seeking to snap her audience out of complacency. But the Playground Series is relentlessly bitter, offering no way out, no solution. The most obvious mark of Lynn’s pessimism is her use of the playground as a metaphor for The System. In the counterculture period, there was ambivalence around play. It was viewed as society-in-miniature, a zone where children were prepped for the real world. On the other hand, it was idealised as a space of creativity and freedom, a corrective for the alienation of wage slavery. However, Lynn’s view is all negative. In her playground, play is simply the flip side of work. We play on wheels, then are broken on them. Play is heartbreaking.

The Playground Series may be of its time, but it’s interesting to see how its concerns were picked up in the early 1990s by po-mo artists concerned with social conditioning, particularly Ruth Watson, Derrick Cherrie, and Michael Parekowhai, all of whom made enlarged toys and games. With a talent for spotting covert messages in the most benign things, Ruth Watson enlarged a snakes-and-ladders board to draw attention to its Christian subtext. Derrick Cherrie cast nursery furnishings as a means to constrain and socialise children. Michael Parekowhai reproduced toys and games, simultaneously drawing attention to their conservative politically-loaded subtexts and showing how they could be repurposed to generate alternative points of view on history and culture, making play seem potentially empowering. In his work, we find light at the end of Lynn’s critical tunnel.

.

[IMAGE: Vivian Lynn Playground II 1975]