Eyeline, no. 73 (2011). Review, Unnerved: The New Zealand Project, Queensland Art Gallery, Brisbane, 2010.

Since the advent of the Asia-Pacific Triennial (APT) in 1993, the Queensland Art Gallery (QAG) has developed a real taste for New Zealand art, assembling what must be the largest institutional collection of contemporary New Zealand art outside New Zealand. They have bought a lot, and they have bought thoughtfully and ambitiously. QAG’s New Zealand art show Unnerved: The New Zealand Project was almost entirely sourced from its collection. Unnerved was a big show, filling the Gallery of Modern Art’s (GoMA’s) ground-floor. To tell the truth, it was too big and tried to tick too many boxes. It wasn’t clear whether it was intended as a broad survey of recent New Zealand art (implied by the subtitle The New Zealand Project), as a more specific exploration of a particular ‘unnerved’ vein within it, or simply as a progress report on the state of QAG’s New Zealand collection. Indeed, it was something of a tug-of-war between all three.

Unnerved was heavily informed by the APT. It dealt essentially with art and art ideas from the 1990s on, and reflected the APT’s penchant for cultural-identity art. It was heavily skewed towards Maori and Pacific Island work. The ethno-pop of APT alumni Lisa Reihana and Michael Parekowhai was well represented. John Pule’s tapa-inspired paintings and Julian Hooper riffing on his mixed Hungarian/Tongan heritage seemed tailor made.

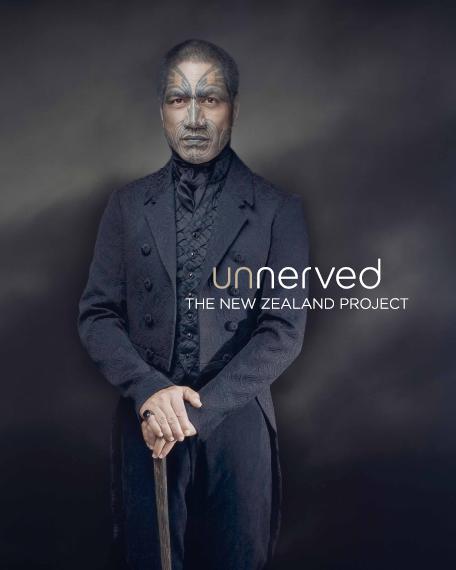

Unnerved was also cued to what has been called ‘New Zealand Gothic’. Most of its key curatorial links and conceptual sight-lines were based on tropes of darkness, death, and the uncanny—an unhealthy obsession with the past. Photographs by Lawrence Aberhart, Mark Adams, and Gavin Hipkins lingered on the New Zealand landscape as haunted—a place of unfinished business where the dead have yet to be laid to rest; those by Ronnie van Hout, meanwhile, satirised this idea. Death and memorials abounded, with Peter Peryer’s images of a dead steer and the Marsden Cross, Shane Cotton’s of mokomokai, Fiona Pardington’s of dead kiwis, and Michael Parekowhai’s of artificial-flower arrangements named for World War I killing fields. Colonial-period retro was also evident: in Aberhart’s old-school plate-camera photography, in Shane Cotton’s ye-olde typography, in the historical garb of Lisa Reihana’s Maori Dandy (reproduced on the catalogue cover), in the lacy modesty of Yvonne Todd’s Limpet, in Nathan Pohio’s blurry video of tall ships, and in bible references scattered here and there.

The idea of a New Zealand Gothic emerged relatively recently as a way to elevate some marginalised artists and ideas within New Zealand art, but it is fast becoming an interpretative default setting. It’s a rubbery notion that has been used to link work that addresses the ghosts of our colonial history with work, such as Todd’s, that has no specific interest in New Zealandness, in order to argue a unifying ‘New Zealand sensibility’. While there may be some truth in it, the New Zealand Gothic idea risks characterising New Zealand art as backward: obsessed with the past, superstitious, and essentially anti-modern. It also excludes a lot. In Unnerved, swathes of work that had been crucial in shaping the New Zealand art discussion simply didn’t get a look in; abstraction was irrelevant, as was Billy Apple.

That said, there were works that distracted from the New Zealand Gothic thematic core, suggesting the show had a broader mandate, which, ultimately, it did not deliver upon. These works included a crowd-pleasing multi-channel video installation by Alex Monteith, featuring acrobatic airplanes doing synchronised barrel rolls; works-on-paper by New-York-based expat Max Gimblett; and a still life of egg shells in a colander by regional realist Michael Smither. From 1967, the Smither stuck out like a sore thumb, being about fifteen years earlier than any other work and entirely irrelevant to the unnerved flavour. Also, if the show was aiming to provide a big-picture account of New Zealand art of the last twenty years, it was simply bizarre not to include key figures like Et Al., Julian Dashper, and Peter Robinson while giving gigs to emerging figures such as James Oram, Campbell Patterson, and Lorene Taurerewa.

QAG is collection focussed. It draws heavily on its collections in mounting shows, and purchases works with shows in mind. While this makes for a big collection, it also limits the ways QAG’s curators can construct both their exhibitions and their collections. Shows can be compromised by having a limited pool of works to draw upon; similarly, the quality of acquisitions can be constrained by having to serve the immediate interests of specific shows. Both tendencies are apparent in Unnerved. On the one hand, the absence of Bill Hammond—an artist utterly central to the show’s New Zealand Gothic theme—seems bizarre. QAG may have been priced out of the market for a Hammond (who was in APT3 in 1999), but surely this was the occasion to borrow one (QAG did borrow Parekowhai’s inflatables from the National Gallery of Victoria). On the other hand, works seemed to have been acquired to permit curatorial juxtapositions in the show. In Unnerved, Gavin Hipkins was represented by The Homely, his ‘post-colonial Gothic novel’, rather than, say, his modernist photograms. The post-modernist Richard Killeen was represented by a pointedly primitivist work featuring stick figures paddling canoes (which chimed with Michael Stevenson’s rustic Fairweather raft and Pohio’s tall ships). Fiona Pardington had her tikis and kiwis rather than her big-breasted good-time girls, and Jacqueline Fraser was represented by the explicitly Maori-themed work she has long since turned her back upon.

Since opening GoMA, QAG has been perfecting a curatorial house style, a distinctive way of making shows. In Unnerved, one sees curatorial conceits reiterated and recycled from other recent QAG shows. The show’s subtitle The New Zealand Project links it to 2009’s The China Project. Where Andy Warhol (2007) incorporated Warhol’s forays into mainstream television and Optimism (2008) showcased Kath and Kim, Unnerved ropes in the Flight of the Conchords. With GoMA’s Australian Cinémathèque, it has also become obligatory to argue a link between art and cinema. Woodenhead, Florian Habicht’s carnivalesque feature, was included within Unnerved, and there was also a massive clip-on cinémathèque program, New Zealand Noir, charting the dark side of New Zealand cinema.

The proximity of New Zealand Noir overstated the parallel between New Zealand cinema and New Zealand art, as if they were driven by the same imperatives or shared the same sensibility. In reality, there is more disjunction than alignment. In the late 1970s, as New Zealand art was casting off nationalism, a New Zealand film industry premised on ‘telling our stories’ was just emerging. The gravity of New Zealand Noir (with its hero image drawn from The Piano) bent everything back to New Zealandness, and fostered the impression that Unnerved was not about ‘the dark side’ of New Zealand art, but that New Zealand art and New Zealand as a whole are dark—which is not especially true.

Unnerved provided a strangely enclosed and nationalistic take on New Zealand art. Constructed through the prism of its own concerns and strategies, QAG offered a view of New Zealand art that seemed genuinely uncanny to me as a New Zealander—rendering my home unhomely. As much as QAG showcased some great artists and great art, its purchase on New Zealand art was compromised by trying to serve too many agendas and by not considering the play of its own desires in framing the art of an other.