Eyeline, no. 88, 2018.

‘This under-planned, poorly executed, elementary level artwork that uses Black women and men as props and controversy starters is over-intellectualized by classist, utterly inept, pompous, and clueless curator types. The world of art gets no more white and privileged than this.’ So wrote black activist artist Damon Davis in September 2016, as he called for a boycott of Direct Drive, Kelley Walker’s survey exhibition at Contemporary Art Museum St. Louis (CAM).1 Davis was protesting the inclusion of decade-old works in which images of black people were obscured by smears of chocolate and toothpaste.

In the US, the drama around Walker’s show would be just one in a string of rows over ‘privileged white artists’ presuming to represent or speak for ‘Others’ in their work. Earlier in the year, Cindy Sherman had been in the crosshairs for adopting ‘black face’ in Bus Riders, an art-on-buses project she made as a twenty-two-year old back in 1976. Hashtag Cindygate. In 2017, there would be outrage at the inclusion of Dana Schutz’s painting Open Casket—based on a famous photo of the disfigured corpse of 1950s child martyr Emmett Till—in the Whitney Biennial. Artist Parker Bright became an Instagram hit standing before the painting, blocking the view, wearing a t-shirt inscribed ‘Black Death Spectacle’ and ‘No Lynch Mob’. Artist Hannah Black called for the painting to be not only dropped from the show but destroyed. Then, Sam Durant got into strife for installing his 2012 gallows sculpture, Scaffold, in the sculpture garden at the Walker Art Center, Minneapolis. He said he wanted white people to acknowledge a shameful mass hanging of Dakota Indians in 1862. But, the Indian community itself—not consulted—didn’t want to be reminded. With Durant’s agreement and apologies, the work was demolished.

For what it’s worth, in all four cases, these privileged white artists would not have considered themselves antagonistic, yet objections to their works were extreme. Little consideration was given to any good intentions or other possible readings. Indeed, these were trivialised in the face of oceans of suffering, aeons of pain. The artists and their works were cast as symptoms of huge, insurmountable problems.

In the US, the culture wars have been changing the relationship between art and politics since the late 1980s. In 1989, after the National Endowment for the Arts supported shows featuring Andres Serrano’s blasphemous Piss Christ and Robert Mapplethorpe’s gay S&M images, conservative Christian politicians (senator Jesse Helms is the one we remember) clamped down, insisting the agency enforce community standards. The following year, NEA grants for four edgy performance artists—Karen Finley, Tim Miller, John Fleck, and Holly Hughes—were vetoed, despite passing peer review. Soon, the NEA, under pressure, would move away from funding individual artists.

But, in 1993, the art world bit back, when the Whitney Biennial presented a diversity lineup, with work addressing a spectrum of left-wing concerns. At the time, the show was slated for emphasising politics at the expense of art, but it proved to be a gamechanger. Critic Jerry Saltz would later write: ‘Establishment art history circa 1993 was … built on white men and Western civilization and certain ossified ideas about “greatness” and “genius”. New artists looking for new ways to speak to new audiences couldn’t get their voices heard or work seen … That biennial marked the effective end of visual culture’s being mainly white, Western, straight, and male.’2

Since then, art and identity politics have been joined at the hip. For art, this has meant greater political awareness and diversity, but also new expectations and restrictions. In art, identity politics has been alloyed with other tendencies: with postmodernist pluralism (which had already weakened formalist arguments about artistic development), with revisionism (forever shunting the marginal to centre stage), with globalisation (which expanded the game, bringing a wide world of Others into the picture), and with art-museum populism (pursuing bigger, broader audiences).3 In the new dance, identity politics often takes the lead, leaving art on the back foot. Enter Kelley Walker.

Walker is a celebrated New York–based white-male artist. He’s blue chip; he shows with Paula Cooper Gallery. His often nerdy, highly theorised works explore the mediation of images in our mass-media society. He has a penchant for working with found media images of black Americans, ranging from celebrities (including Whitney Houston, Michael Jackson, Sonny Liston, and Little Richard) to anonymous figures in 1960s civil-rights protests. In St. Louis, works from two series—Black Star Press (2004–5) and Schema (2006)—became the focus of concern.

The Black Star Press works re-present a press photo from a 1963 civil-rights protest in Birmingham, Alabama, showing a young black man being attacked by a white policeman with a dog. Taken by Bill Hudson, it was originally published in the New York Times. Walker enlarges it, flips it (a Coca-Cola sign in the background is clearly reversed), rotates it through ninety-degree increments, and prints it in black or Coca-Cola red on white, black, or Coca-Cola-red, on canvases. Across the image, he then screenprints expressionist-looking ‘splatter’ in dark, milk, and white chocolate.4 The splatter is graphicised, and, in places, even rendered in outline. It’s expressionism in quote marks.

While they deal with a heavy historical subject, these works are clearly also art about art, juggling art history: 1940s–1950s abstract expressionism (Jackson Pollock), the 1960s pop art that superseded it (Andy Warhol), and 1980s appropriation art (Richard Prince and Sigmar Polke). The Warhol connection is pointed. Walker is riffing on Warhol’s Race Riot paintings (1963–4), which reproduced different black-and-white press photos of police with dogs attacking black civil-rights protestors in Birmingham in 1963 (Charles Moore shots published in Life).5 Warhol made his works soon after his source photos were published, Walker forty-plus years later.

The Schema works are billboard-scale enlargements of covers from the then-current, now-defunct black men’s magazine King—‘the illest men’s magazine ever’. The covers feature sexy images of black women—models, musicians, and actresses. Walker scanned trails of toothpaste and digitally incorporated them into the cover images.

Direct Drive opened at CAM on 16 September 2016. In one room, Walker presented Black Star Press and Schema works together. There were two Black Star Press works: a diptych, with the photo rotated 180 degrees, and printed red on white and black; and a triptych, the photo rotated 90 degrees, printed black on white. There were three Schema works, produced as giant stickers, wall scale, and overlaid. Only Schema; Aquafresh plus Crest with Whitening Expressions (Trina) was fully visible, with the edges of the others poking out beneath it. Turning her face and backside towards us in a stock sexy pose, the cover girl, rapper Trina, stands in front of a military-style camouflage background wearing underwear and a bullet belt.6

Things came to a head the day after the opening, during the artist talk. Walker was questioned by members of the public about his interest in black bodies and racial conflict. While happy to describe his works’ technical aspects at length, he proved unwilling or unable to answer their questions. They found him cryptic, evasive, condescending. When the show’s curator, Jeffrey Uslip, sprung to the artist’s defence, he was seen as inadequate and arrogant, shutting down a conversation that needed to be had.

Damon Davis was at the talk. In a Facebook post, he called on audiences to boycott CAM until it removed the offensive works and apologised to the black community. He wrote: ‘If I took pictures from the holocaust and smeared peanut butter on them, the entire world would be at my throat.’ There was a groundswell of agreement. On 18 September, three black front-line CAM staff—Community-Engagement Manager De Andrea Nichols, Educator Lyndon Barrois Jr., and Visitor-Services Manager Victoria Donaldson—wrote to CAM’s directors. They argued that Walker’s work ‘triggers a retraumatization of racial and regional pain’. They wrote: ‘works within the Black Star Press inflict additional insult and injury to the injustices of our time. To provide a white, male artist the entirety of the museum and include works of this nature positions the museum and its staff in implicit support and perpetuation of these societal ills.’7 They demanded that the works be removed, that the artist and curator apologise, that the curator resign, that the video recording of the talk be released, and that CAM’s curatorial policies be reassessed. Big demands. The media jumped all over it.

Executive Director Lisa Melandri was caught in a pincer action, under attack from within and without, making it impossible to close ranks. Strangely, no-one called for her resignation. CAM would respond: ‘First and foremost, CAM would like to reiterate our apology to the community for the anger and pain we caused. Our mission as an institution is to be a place where all can experience contemporary art in a space free from discrimination, judgment, and disrespect. It is clear, from the community’s response to Kelley Walker’s artist’s talk on September 17, that we failed to provide a place where all voices could be heard.’

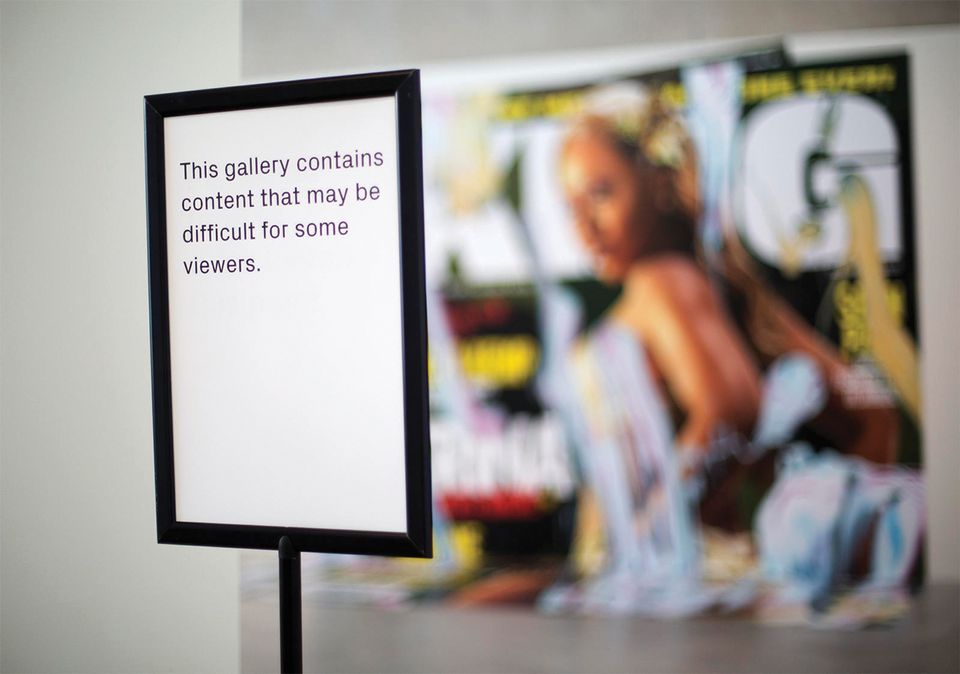

The artist and curator also apologised, and the curator packed his bags—though he may have been leaving anyway. CAM didn’t remove the works, but had a large wall built blocking the view and added warning signs and dispensers containing printouts of media coverage of the controversy. It also designated a ‘Your Words Here’ wall, where visitors could express their views on post-its. A panel discussion organised by the local visual-arts group Critical Mass, ‘Art and the Black Body’, was rejigged to address the show directly. None of the panellists defended the work.8

Melandri had hoped the show would generate a productive, timely discussion about the depiction of black bodies, but was unprepared for the sheer negativity of the response. She said that the work itself was just one contributing factor in a ‘perfect storm’.9 Other factors were the personalities of an artist (unwilling or unable to respond to questions) and of a curator (perceived as snotty), her elegant white-cube museum (where local artists feel excluded), the new activist space of social media (where complaints spread like wildfire among like minds), and, crucially, the racially divided city of St. Louis itself.10 It was in Ferguson, in Greater St. Louis, in 2014, that the unarmed black teenager Michael Brown was fatally shot by police, leading to days of protest and rioting. Since then, the city has emerged as an epicentre for a new civil-rights movement, spearheaded by Black Lives Matter.11

At CAM, Walker’s show hit a raw nerve. In hindsight, it was naive programming and bad timing. It showed the institution to be out of step with its audience, even its staff. The critics were righteous (justified by a history of oppression and disempowerment) and vigilant (predisposed to respond swiftly). They projected a web of pre-existing issues and hurt onto Walker’s works. But, in the rush, the works’ subtleties and insights were overlooked. I’d like to offer an alternative reading.

But, first, let me address the criticisms. Walker’s critics characterised his works as racist, but offered little in the way of readings to substantiate this. It was more about gut responses: they were offended, so the works were offensive. And the offence proved contagious, with gut responses prompting and affirming one another—snowballing. The precise problem also proved elusive, migrating like a pea in a shell game. Sometimes it seemed to lie with the art itself (what it said), sometimes with Walker being white (suggesting the works might have been okay if a black artist had made them), sometimes with Walker’s deficiencies as a public speaker, and sometimes with his art-world success (as if this had necessarily come at the expense of black artists). Issues with the art, with the artist, with CAM, with the art system, and with the wider world were linked. Criticisms of the works became conflated with and inseparable from criticisms of CAM and calls for it to include more ‘voices’—meaning local artists (most of the critics being local artists). So, capital-P Politics and art-world politics, higher principle and self-interest, became entwined.12

With the Black Star Press works, there was a concern that Walker was being exploitative—profiting from the pain of black people. But, even if there’s truth in this, it’s a slippery slope. As Coco Fusco pointed out later, when the same concerns were levelled at Dana Schutz: ‘… black artists have also accrued social capital and commercial gain from their treatment of black suffering. Numerous black artists have depicted enslaved bodies, lynched bodies, maimed bodies, and imprisoned bodies’.13 Although some questioned Walker’s right to address ‘black images’, celebrated black artist Glenn Ligon had already overturned this objection. Writing on Walker in 2010, he asked the obvious question: it has a black body in it, but is the Birmingham photo really a ‘black image’? Not only does it also include a white body, it is a mainstream-press image, a dominant-culture image, a ‘white’ image. It speaks of white as much as black; it speaks of ‘America’. Ligon went on to write, provocatively: ‘Walker is a good American boy, because he, like many other white Americans, has a healthy, wholesome, complicated, troubling, and troubled obsession with black people, an obsession that I confess I happen to share … let us think of Kelley Walker’s “negro problem” as an American dilemma, a dilemma which gives enormous vitality to his work and one which we ignore at our peril.’14 But, in St. Louis, Walker’s critics tended to overlook this ambiguity.

Walker’s Black Star Press works are at war with themselves. History painting (the photo) and abstract expressionism (the chocolate smears) are deadlocked in a pictorial arm wrestle. Yet his critics tended to read them just one way, identifying the artist with the smears that supposedly defile and drown the image of the black man. But, the works could instead be read as if the artist were on the photo’s side, with its reality erupting through the chocolate splatter—that is at once a ‘sugar coating’ and abject shit—in a return of the repressed. Isn’t Walker reminding us that, back in the day, the US used abstract expressionism to promote itself as the epitome of freedom, masking its racism?

With his Schema works, Walker was said to be sexualising black women. But, surely he was addressing the fact that black women are already sexualised, and for and by black men. The King covers are the sort of ‘acceptable’ soft-core images that can be seen on the covers of men’s magazines on newsstands everywhere. They speak to a kind of racial equality—the black male gaze is also catered for and black women are equally sexualised. However, the covers are also a mixed message, speaking both of sovereignty (‘king’) and segregation (a black media addressed to black people).

It was said that Walker sexualised the women by adding the toothpaste smears—‘jizz-like gobs’, Danny Wicentowski called them.15 But one might also say that the women sexualised the toothpaste, by association. Walker has used toothpaste smears elsewhere, where they read differently. In one work prominently featured in Direct Drive, he added toothpaste smears to a documentary image of a ruptured airplane. Here, the paste becomes, in the eyes of critic Scott Rothkopf, ‘an antiseptic body eerily at odds with the traumatized ones exposed within the mangled fuselage’.16 Walker plays on the way we read the toothpaste differently in different contexts. In a sexual context, it’s sexual; in a disaster context, it’s medical. It’s the Kuleshov effect.

In the Critical Mass panel discussion, Katherine Reynolds linked the use of toothpaste to the way the Schema images extended onto the floor: ‘Putting toothpaste that looks like semen [onto her body] and allowing people to walk on her body … as a black woman that is not okay, as a woman that is not okay.’17 But, it is a stretch to say that, by running the Trina image onto the floor, Walker was inviting visitors to ‘walk on’ black women. At CAM, the Schema image felt oppressively huge. There was no implicit invitation to walk on it. The effect was more of the work—and Trina within it—dominating viewers, colonising our space, limiting our room to move. In making the King covers monumental, Walker could have been mocking Trina’s lack of power or asserting her excess of it. Yes, her bullet belt could be coy and ironic (if she has no power), but it could also imply militancy (making her an empowered phallic woman). Which way you read it may say more about you than about the image.

Walker’s critics often asserted his works’ pernicious influence by imagining their potential effect on children.18 In doing so, they envisaged a very different world, in which art is normative—where empty, innocent heads might be decisively formatted and corrupted through exposure to Walker’s art. But, that’s not the world we—and our children—live in. Mass-media culture may be normative, but art isn’t. It doesn’t get to enough of us early enough, clearly enough, or often enough to mould the way we think. It comes later, offering disruption and interference. And it seems disproportionate to damn Walker’s show—presented in a discursive context (an art gallery), to a small, relatively niche, knowing audience—when there are more insidious and pernicious images circulating in the mass media, more effectively framing what and how people think. Surely, this is why Walker works with loaded mass-media images, already in circulation, unquestioned.

Now, my alternative reading. I think Walker’s Black Star Press and Schema works are politically productive in raising thorny questions as to how we as viewers are implicated in dilemmas about racism, sexism, and their intersection. In repeatedly reproducing mass-media images and in coating them in supermarket commodities (chocolate and toothpaste) and rendering them in Coca-Cola corporate colours, Walker locates these dilemmas squarely within capitalism. His works are about the way compelling images are addressed and commodified.19

While they are meaningful in themselves, the Black Star Press and Schema series also play off one another, scrambling racial politics and sexual politics, generating interference patterns. That’s why works from these series are habitually shown together and are discussed in the same breath. We are cued to read the Schema works through the Black Star Press ones, in a play of similarities and differences. The Birmingham photo belongs to the mainstream white media of the past, the King covers to the black media of the present (more or less). Walker treats the Birmingham photo through flipping, rotation, and enlargement, and by adding actual chocolate, and treats the King covers through enlargement, and by incorporating images of toothpaste. He makes us discriminate between (actual) chocolate and (reproduced) toothpaste; between dark, milk, and white chocolate (literally and metaphorically); between whitening toothpaste and white chocolate. Etcetera.

By juxtaposing his Black Star Press and Schema works, Walker prompts us to consider how times have changed and how they haven’t. Together the two series imply a narrative from earlier to later, from then to now. Not only were the Black Star Press works made before the Schema ones, they have an earlier source image (forty-plus-years earlier), while the Schema works use an almost current source (you can read the dates of the King issues). The Birmingham photo is about race politics and direct violence; the King cover brings in gender politics and sex (though violence is implicit in the bullet belt). Both images involve relationships. In the Birmingham photo, the principal relationship is between the white-male policeman and the black-male protestor within the picture. With the King cover, it’s between the black woman and the viewer beyond the frame that she eyeballs. The Birmingham photo in the Black Star Press works positions oppressor and oppressed explicitly, so, when we move to the Schema work, we are cued to look for villain and victim. But, here, only one figure is visible—Trina. So, which is she? Here, the reciprocal role is taken by the viewer, both notional (the King reader) and actual (us, now, looking at the enlarged cover transposed into an art gallery). Are they or we her oppressor or her oppressed?

How should we make sense of all this? Can we? Has the black man, explicitly oppressed by the white policeman in 1963, become the implicit, invisible, off-screen sexist oppressor of the black woman in 2005—a ‘king’? Would this make Trina his erotic compensation for past oppression? Or, does she actually represent his new, awesome, towering oppressor, with police dog replaced by bullet belt? Where is the power here? Is the ‘king’ a Martin Luther King or a Rodney King? Whose chocolate has become whose toothpaste? What has been whitened? And, as viewers, where do we stand, where are we asked to stand, and where are we able to stand, in this displacement puzzle? What is the difference between the implied viewer of the King magazine cover on the newsstand and the actual viewers of Walker’s work in the gallery? How does it feel, as, say, a white male or female—or, indeed, as a black male or female—to be positioned, in the gallery, by the artist and by Trina’s blind gaze, as the implied black male?20

I appreciate that Walker’s critics wanted to make their point and not be distracted by ambiguities and counterclaims—the stuff Damon Davis dismisses as ‘over-intellectualized’. Strategically, perhaps, they accorded the works a clearly evil meaning to make them easier to dismiss. But things were never so simple, and the risk is throwing out the baby with the bathwater. Any art worthy of the name trafficks in ambiguities and problems, and emphasises the mediating quality of language—otherwise it’s not art, just illustration or ideology. Art is there to stretch us. Art doesn’t take the blue pill and accept the world as represented; it takes the red pill and goes down the rabbit hole.21

Walker doesn’t illustrate the way the world was, is, or should be. He disrupts representation to create an interpretative dilemma. He messes with us. Yes, his works are obscene, nasty, and embarrassing; he puts us in a sticky place, positioning us (in public) as the voyeurs we would prefer not to be, leaving us in a quandary.22 Yes, he conjures with racism, but a racism already there in his sources, in our heads, in the world. But, you can’t say his works express a racist view—indeed any view. He’s not saying, ‘This is my view of black people’, but, rather, ‘What happens if I take this image and do this and that to it? How does that change things for you?’ The steps he takes in détourning his source images are simple and explicit, so we can reverse engineer the upshot of each turn of the screw. Walker is not trying to tell us what to think but prompting us to think, by exposing the way we do think.23 But, in St. Louis, his critics were disinclined to acknowledge his quote marks and question marks—to see his art as art. Instead, it was read as representation.

The Walker controversy was a symptom. It points to a deeper art-world fault line, where a corrosive avantgardism (that questions) grinds against a prescriptive identity politics (that already has answers). Other tensions are implicated here; for instance, between the rights (and wrongs) of artists pursuing their inquiries as individuals and the responsibilities (and irresponsibilities) of institutions presenting and framing their works on behalf of communities—stakeholders, taxpayers, citizens. But, still, this is only part of the picture. As extreme as the clash between Walker and his critics was, it could be seen as being between parties, broadly speaking, on the same side of politics. We need to view it in a wider context and against the background of changes in US society—changes that occurred between when Walker’s works were made in 2005–6 (in between the launch of Facebook in 2004 and Barack Obama’s election in 2008) and when they were shown in St. Louis in late 2016 (as Donald Trump was being elected).

In the intervening period, as America’s first black president enjoyed two terms, social media came to rule our lives. We are now learning a bitter lesson, that, rather than connecting diverse people to create a utopian space of public discourse, the Internet isolates and polarises us, fostering extremism. In her book, Kill All Normies, Angela Nagle observes how online subcultures have transformed the US political landscape, paving the way for Trump.24 On the one hand, we’ve seen the growth of a left-wing ‘slacktivist’, ‘snowflake’ subculture (concerned with virtue-signalling, social justice, trigger warnings, and safe spaces). On the other hand, a toxic alt-right subculture has also emerged (eschewing political correctness and trolling liberals, feminists, and minorities). This alt-right is far removed from the Christian old-right that condemned Serrano and Mapplethorpe last century. Indeed, Nagle argues, the alt-right has learnt from the old left’s postmodernist strategies of irony, play, and transgression. Meanwhile, the left itself has become more prescriptive, like the conservative old right; it has great expectations. So, a decade after they were made, Walker’s works found themselves in a new situation.

I don’t want to make enemies of Walker’s critics. Nor does he, I’m sure. I understand the overwhelming issues and resentments that underlie their sensitivities, their cause. In the US, race politics remains the big question. But, even if Walker is privileged, even if he is a wretched public speaker and can’t explain himself, and even if he doesn’t satisfy a call for positive representations, I still don’t think his works are as hateful or harmful as his critics suggest. While I don’t want to argue that artists should automatically have get-out-of-jail-free cards, I don’t think they should be made examples of either—held responsible for all the ills of the world that their works refer to, ills that precede and exceed them. Walker’s works deserved a more generous hearing in St. Louis, but, in the current climate, with the simultaneous rises of Black Lives Matter and Donald Trump, they will find it hard to get one.

In the US, in the late 1980s and early 1990s, things seemed simpler, with the art world on one side and Christian conservatives on the other. But the battle lines have been redrawn. Now, we find artists turned against artists and museums against art. And, while Damon Davis wants us to boycott CAM to make things better, Trump threatens to defund the NEA to help make America great again.25 Catching Walker’s unruly art between a rock and a hard place, the culture wars have shifted into a new phase, reducing art’s elbow room.

- ‘In the Face of Male White Privilege Run Amok: A Plea for Artistic Responsibility’, Hyperallergic, 28 September 2016, https://hyperallergic.com/325780/in-the-face-of-white-male-privilege-run-amok-a-plea-for-artistic-responsibility/.

- Jerry Saltz and Rachel Corbett, ‘How Identity Politics Conquered the Art World: An Oral History’, New York, www.vulture.com/2016/04/identity-politics-that-forever-changed-art.html.

- Art-museum populism is itself conflicted, often showing an inability or unwillingness to differentiate between a patrician desire to democratise culture (broadening audiences for art) and a proletarian call for cultural democracy (broadening art for audiences).

- Walker explains: ‘I start by making splatters of real chocolate on glass and scanning them. I then use this digital image to make a silk screen, through which I print chocolate directly on the canvas. An important aspect here is that the chocolate remains constant in the painting both as a material and as a representation of itself, because you’re basically printing an image of chocolate with chocolate. I also saw it as a way of using silk screen like Warhol and Rauschenberg while marking my temporal and conceptual distance from them.’ Vincent Pécoil, ‘Printed Matter’, Flash Art, March–April 2006: 64.

- One of Warhol’s Race Riot paintings was once owned by Robert Mapplethorpe. It reproduces the image four times, over red, white, and blue canvases, suggesting an American flag. In 2014, it fetched $US62.885 million at auction.

- The cover makes other militaristic references. The issue description, ‘The American Pie’, is written in an army-style stencil face. Under it are teasers to magazine contents: ‘Sacha Kemp: Brings Sexy Soldiers to the Battlefield’ and ‘America’s the Bomb!’

- hyperallergic.com/wp-content/uploads/2016/09/SKMBT_C45416092213521.pdf. The letter was released to the public on 22 September 2016.

- The Critical Mass panel featured eight speakers, all black, mostly local artists: Dr Rebecca Wanzo (Associate Professor, Women, Gender, and Sexuality Studies, and Associate Director, Center for Humanities, Washington University in St. Louis), Katherine Reynolds (artist), Lyndon Barrois Jr. (artist, CAM educator, and visual-arts professor), Kahlil Irving (artist), Vanity Gee (Director of Community Programs and Grand Center Operations, Craft Alliance Center of Art + Design), MK Stallings (Founder of UrbArts, poet, writer), and Dani and Kevin McCoy (artists, designers). https://criticalmassart.org/art-and-the-black-body/.

- In conversation with the author, December 2016.

- St. Louis’s Delmar Boulevard—known as the Delmar Divide—largely separates black communities (to the north) from white ones (to the south). See Jeannette Cooperman, ‘The Story of Segregation in St. Louis’, St. Louis, 17 October 2014, www.stlmag.com/news/the-color-line-race-in-st.-louis/.

- The three CAM staffers use the expression ‘epicentre of a new civil-rights movement’ in their letter. The activist movement Black Lives Matter originated in 2013, after George Zimmerman was acquitted in the shooting death of Trayvon Martin. It became nationally recognised for its street demonstrations following the 2014 police killings of Michael Brown in Ferguson, in Greater St. Louis, and Eric Garner, in New York City.

- Guru Toocool presented his critique on YouTube. In it, he calls Uslip a ‘dirtbag’ and says he needs to be fired and that Walker should be ‘bitch crapped’ (although he may have meant bitch slapped). Toocool ends his video by showing his own paintings, explaining ‘I’m going to show you some of my own art pieces that perhaps should be in its (Walker’s) place.’ www.youtube.com/watch?v=5VDwEIfxYgI.

- Coco Fusco, ‘Censorship, Not the Painting, Must Go: On Dana Schutz’s Image of Emmett Till’, Hyperallergic, 27 March 2017, https://hyperallergic.com/368290/censorship-not-the-painting-must-go-on-dana-schutzs-image-of-emmett-till/.

- ‘Kelley Walker’s Negro Problem’, Parkett, no. 87, 2010: 81.

- ‘Gallery Defends Kelley Walker: Artist Under Fire in CAM St. Louis Exhibit’, Riverfront Times, 30 September 2016, www.riverfronttimes.com/newsblog/2016/09/30/gallery-defends-kelley-walker-artist-under-fire-in-cam-st-louis-exhibit.

- Scott Rothkopf, ‘File Sharing: Scott Rothkopf on Kelley Walker’s Untitled (2006)’, Artforum, September 2012: 455–6.

- https://criticalmassart.org/art-and-the-black-body/.

- For example, Damon Davis on Facebook: ‘Schools take black children to this gallery, when they see these images, they are being told that their bodies, their history and their stories are disposable and always up for use by any privileged white man and institutions that feels like using them to get some press.’ Or Davis again, to The Art Newspaper: ‘My daughter goes to school up the street. This is the first intro that most kids get to what art is supposed to be. This is what smart people like. This is what rich people like. This is what smart people and rich people think of you. You’re a decoration. Your pain is decoration.’ http://old.theartnewspaper.com/news/museums/artist-activist-calls-for-boycott-of-st-louis-show-due-to-institutional-racism-/. Or Chris Naffziger: ‘Earlier last week, I imagined a mother walking down Spring Avenue from her home in the nearby JeffVanderLou neighborhood, and, on a lark, deciding to come into the museum with her children. What is she supposed to think? What are her children going to get out of this exhibition?’ www.stlmag.com/arts/visual-arts/kelley-walkers-problematic-cam-show-where-do-we-go-from-here/. Or Pamela Fraser: ‘The public continued to express the pain of having to see these images, and some expressed the sadness and confusion of having to try to explain the work to their children.’ http://badatsports.com/2016/subversion-of-what-kelley-walkers-direct-drive-at-cam-st-louis/. Or Guru Toocool: ‘So the question is … how would you explain this kind of art to a child?’ https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=5VDwEIfxYgI.

- For a discussion of Walker’s work in relation to capitalism and class, see Walter Benn Michaels, ‘Race, Class, and Kelley Walker: A Tenth Disaster’, Flash Art, January–February 2017: 19–23.

- In the same room as the Black Star Press and Schema works, there was another work that, surprisingly, was little mentioned in the furore. White Michael Jackson (2016) reproduced a press photo of Jackson after he was arrested on child-abuse charges in 2003. The white-on-white canvas was keyed to Jackson’s assumed skin bleaching and a nod to Walker’s whitening toothpaste.

- The philosopher Slavoj Žižek could have been describing Walker’s works to a T when he wrote: ‘A modernist work of art is, by definition, ‘incomprehensible’; it functions as a shock, as the irruption of a trauma which undermines the complacency of our daily routine and resists being integrated into the symbolic universe of the prevailing ideology; thereupon, after this first encounter, interpretation enters the stage and enables us to integrate this shock—it informs us, say, that this trauma registers and points towards the shocking depravity of our very normal lives …’ Slavoj Žižek, ‘Introduction: Alfred Hitchcock, or, The Form and its Historical Mediation’, in Everything You Always Wanted to Know About Lacan but Were Afraid to Ask Hitchcock, ed. Slavoj Žižek (London and New York: Verso, 1992), 1.

- I’m reminded of the famous Ad Reinhardt art cartoon in which an everyman points at an abstract painting and sneers, ‘Ha Ha. What does this represent?’, only to have the painting point back, knocking him off his feet, saying, ‘What do you represent?’ Ad Reinhardt, ‘How to Look at a Cubist Painting’, PM, 27 January 1946.

- Or as Uslip puts it: ‘Kelley is not telling us what to think one way or another … he is allowing his practice to help us think through the issues of our time.’ Quoted in Jenny Simeone, ‘St. Louisans Call for a Boycott of CAM’s Newest Exhibit, Direct Drive, Depicting Black Bodies’, St. Louis Public Radio, 20 September 2016, http://news.stlpublicradio.org/post/st-louisans-call-boycott-cams-newest-exhibit-direct-drive-depicting-black-bodies#stream/0.

- Angela Nagle, Kill All Normies (Arlesford: Zero Books, 2017).

- Andrea K. Scott, ‘Trump’s N.E.A. Budget Cut Would Put America First, Art Last’, The New Yorker, 17 March 2017, www.newyorker.com/culture/cultural-comment/trumps-n-e-a-budget-cut-would-put-america-first-art-last.