Terry Urbahn (Auckland: Anna Bibby Gallery, 2003). Ten texts written in response to ten projects by the artist.

1993 Scrooge Invited to do something for a happy-happy Christmas show at Wanganui’s Sarjeant Gallery, Urbahn focused on the bleak side of the silly season. Setting himself apart from the rest of the Christmas crew, he chose a non-exhibition space, a dingy stairwell service area on the way to the loos. There, by chance, he discovered, ready-installed, a massive tatty oil of Joseph and Mary’s Flight into Egypt by Frederick Goodall RA, recalling the slaughter of the innocents, the downside of Christmas. Riffing off the Royal Academician, Urbahn’s ironically titled installation Post-Crash Recovery turned the goodwill season on its head, literally. The artist had some local convicts uproot a massive Christmas tree and hung it from the ceiling by its roots. He filled a display case with the optimistic original city plans for New Plymouth and up-to-the-minute photos of its shop windows, some bounteous and tinselly, but an equal number bleak and deserted. On the wall, he painted a tree-like street map of Energy City and wired it with fairy lights; one light for every abandoned shop or deserted showroom, indexing the local recession. In a museum space where 150 lux is the rule, a 3,000-watt bulb dangled from the tip of the inverted tree, beaming out rude secular light. Its glare poured out through the museum and, pointedly, through its star attraction—a feel-good Chris Booth installation of miraculously stacked pumice—wrecking its contrived serenity. Bah, humbug!

.

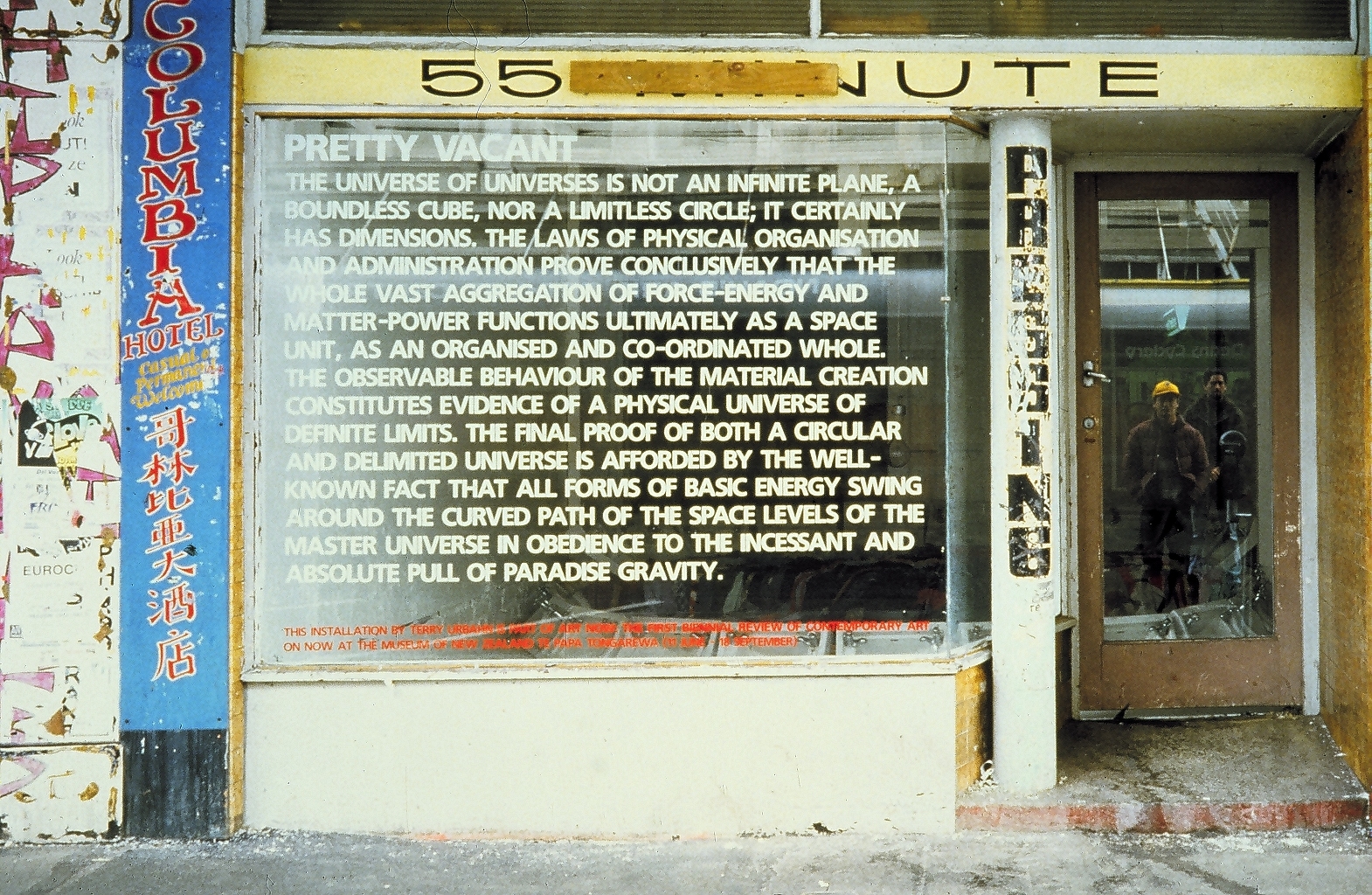

1994 Archaeologist Snooping around Wellington, scoping out empty commercial spaces in which to stage an installation, Urbahn chanced upon an old doss house. Slated for redevelopment into chic boutiques and up-market apartments, the Columbia Hotel was deserted. Given short notice to pack, the inmates had vamoosed, leaving heaps of personal junk. Urbahn approached the site with the glee of an archaeologist, unearthing evidence of how the Columbians once lived. There were old clothes, pages from a teenage diary, hate notes written between lovers in the throes of a break-up, snapshots, and court and psychiatric reports. For his installation in the Columbia’s front windows, Urbahn presented a video reconstructing his descent into the hotel as if it were Pharoah’s tomb, opening a decrepit deep-freeze like some ancient sarcophagus. Four little monitors screened closed-circuit surveillance images, switching between vacant rooms in real time. Vinyl lettering on one window represented a text lifted from a quasi-scientific new-age treatise. Beyond this veil of verbiage you could see a ring of broken hand basins on the floor, containing a whirlpool of old clothes. Presiding over the vortex, Urbahn hung his signature, that 3,000-watt bulb. Titled Pretty Vacant, the work flickered between the new-age and the punk, between evoking cosmic black holes and parading local out-patients. Was this voyeurism, anthropology, or both? Certainly, it was pointedly class-conscious, yet was strangely lacking in social concern.

.

1995 Hero In folklore, the archetypal hero is expelled from the city only to return bringing new knowledge. Invited to make a show for New Plymouth’s Govett-Brewster Art Gallery, Urbahn decided to hold up a mirror to his old home town. A culturescape, Alien Space focused on the three pastimes that had dominated his Taranaki teens: surfing, rugby, and rock’n’roll. Urbahn proffered evidence—surfboards, rugby jerseys, guitars and amps—stacked up through the space like little islands or shrines. He incorporated TVs screening video interviews he’d made with local legends, representatives of his adolescent obsessions: rugby’s Slater Brothers, surf star Jason Matthews, and heavy-metallers Sticky Filth. Into the interviews he spliced excerpts from 2001: A Space Odyssey, famous punk clips, and footage of great surf breaks and All Black tries. David Bowie’s Space Oddity featured in the backing music. Urbahn promoted his show as a sop to the locals, who routinely complain that the gallery is an ivory tower with its back turned on local folk. But really it was more a community challenge—asked-for content but in avantgarde packaging, an aesthetically grating experience. Urbahn’s show détourned the familiar, alienating the audience: giving them what they wanted but not how they wanted it. Home—there’s no place like it.

.

1997 Realist Preparing to become Te Papa, Wellington’s National Museum initiated an overdue spring clean. Old, amateurish, politically incorrect exhibits were purged and replaced with ideologically-sound state-of-the-art ones. Among the displays destined for the dump were several dozen portable display cases from the Museum’s Education Service. Their doors opened to reveal mini-dioramas behind glass and interpretative panels. The cases were once lent to far flung primary schools, whose pupils couldn’t get to Buckle Street. Intricate but clunky, they were museum pieces themselves. Employed during the day at Te Papa, coordinating a team creating new exhibits, at night Urbahn would toil at home, on the kitchen table, modifing the cases. He often used their existing contents as a jumping off point. Far instance, one diorama offered quaint scenes of African village life, with female figurines carrying out domestic duties amongst grass huts before a painted backdrop depicting male hunters. Urbahn updated the idyll, arming the villagers with tiny M16 rifles, grenades, and machine-gun posts. The ‘Dogon’ and ‘Ona’ cases were renamed ‘Hutu’ and ‘Tutsi’, and Urbahn superimposed accounts of atrocities in Rwanda onto the text panels. A case about refining sugar became a home-bake how-to. Recalling Duchamp’s infamous Box in a Valise, Urbahn used some cases to restage miniature versions of his previous exhibitions, reconstructing their casual appearance in painstaking detail. Perhaps Urbahn’s hobby art was compensation: all the politically incorrect thoughts and amateur hobbyist pleasures repressed during his day job returned. Collectively titled Urban Museum Reality Service, Urbahn’s case studies illlustrated Lacan’s notion of the Real as that which ruptures the Symbolic, the accepted and endorsed view. Te Papa bought two.

.

1998 Poseur We go to art museums to celebrate originality, authenticity, and excellence in art. We know how to behave there—quietly, soberly. No running or jumping. A quiet reverence is called for. Urbahn confounded these expectations when he curated a museum touring exhibition in the form of a raucous karaoke bar. Karaoke is an entertainment favoured by Japanese salary men, who let their hair down at the end of a hard day by drinking excessively and standing on stage singing pop standards, imitating the stars to amuse their friends. The karaoke machine is a jukebox in which instrumental tracks are accompanied by inspirational video images with embedded lyrics. Performances range from consummate to crap. In Japan, karaoke is a safety valve—an acceptable, qualified form of individualism. It’s one of the only ways to show off without being branded arrogant or self-centred. Featuring a karaoke machine, a lit stage, a spinning mirror ball, and sound system, Urbahn’s exhibition The Karaokes asked gallery-goers to perform. Urbahn and nine friends—artists who made music and musos who made art—each produced a clip. They included Michael Morley (The Dead C, Gate), Ronnie van Hout (Into the Void), and Violet Faigan (Space Dust). Urbahn’ s own contribution, sPEECHless, explicitly addressed wanting-to-be. It showed the artist in his bathroom, making himself over as a punk, then standing in front of drawn curtains in his lounge playing his bass and lip-syncing to his own rendition of The Stranglers hit Peaches. Urbahn indulged his air-guitar fantasies, with moves, poses, and scowls quoted from countless rock videos and publicity photos. Lyrics appeared on the screen in a military-looking stencil face, spelt phonetically. The aesthetic recalled an earlier work, Cult: three posters in which the artist was crudely photoshopped into the bodies of famous bass players—Sid Vicious from the Sex Pistols, Lemmy of Motorhead, and Sonic Youth’s Kim Gordon. As critic Aaron Lister pointed out, The Karaokes involved a double displacement, simultaneously exceeding expectations of both art and karaoke. Presented in an art gallery, it may have been a bull in a china shop, but it would have been even more out of place in a karaoke bar. Karaoke videos are slick and sentimental. They exemplify an insipid, feel-good popularism. They are about identification, not critique. But these were not the values of Urbahn and his collaborators, who side with the low-fi independent rock music typically filed under ‘alternative’, ‘experimental’, or ‘noise’. Their clips didn’t work as karaoke clips, being either impossible to sing along with (Morley) or mercilessly sending up karaoke’s cheesy values (Faigan). Deeply conflicted, The Karaokes sent out mixed messages about individualism and community, and about whether the artists really wanted the gallerygoer to join in or not. An exercise in layered cynicism, The Karaokes flirted with—but also distanced itself from—both the commodified individuality of the Western rock star and Japan’s hyper-conformism, its repressive communalism.

.

1999 Loner George Orwell’s Big Brother is a cool idea. But, in real life, surveillance is no glamour job. It’s boring, badly-paid work. Nothing happens, and, for most part, the eyes learn little worth knowing of subjects in bank queues and shopping malls, because surveillance is deterrence. Rather than omnipotent, the guy in the monitor room is the cheapest piece of equipment there. We should pity Big Brother. The tragedy of the spy life was played out in Urbahn’s installation COLUMBIA saLOON. He mocked up a video-surveillance workstation in one of the front windows at Wellington’s James Smith Market, dressing his graveyard-shift set with a half-eaten sausage roll, stale cups of tea, the latest Best Bets, and escapist postcards of island paradises. The piece was a self-portrait. In some of the monitors, you could see the artist incognito, dressed as a bad-suit worker-bee, enjoying a drink in the sports bar inside—apparently a live feed from a surveillance camera. Not that anything of interest occurred. There was background activity: people watching the rugby on TV, comings, goings. On other monitors, Urbahn looped his earlier tape from Pretty Vacant, documenting his descent into the Columbia Hotel. Standing on the footpath, you could hear spaghetti-western dialogue about greed and corruption, suicides, lynchings, needing the right qualifications, feeling disenfranchised. Urbahn’s forlorn installation was a meditation on loneliness: the loneliness of the salary man and the tardy husband, the loneliness of the security guard, the loneliness of the artist descending into the dreary doss house—all cross-referenced with our sad-arsed sidewalk selves with nothing better to do than watch.

.

2000 Criminal Class doesn’t figure much as a subject in New Zealand art. It’s unspoken. Even worse, ‘the arts’—where contemporary art meets opera, ballet, choral societies, theatre, ceramics, and ‘quality movies’—is an insistently bourgeois domain, favoured by upwardly mobile farmers’ wives, Remuera matrons, and wine sponsors. This was the meagre demographic courted by Backchat, TV’s arts and current-affairs programme. When the show got the chop in 1999, Urbahn offered to make C:R.U.R.T./Chatback/A Digital Lemon/ to screen as its final item, its parting shot. Wanting to break the mould of the reverential artist-in-his-studio bio-pic segment, Urbahn volunteered to be interrogated as a criminal. He wanted it to look like the Good Night Kiwi had lost it, putting in the wrong tape by mistake. He wanted to jolt the show’s genteel audience, as though revealing some rude truth usually obscured. Not surprisingly, Backchat said, ‘No Way!’ But the show’s intrepid reporter Mark Crysell, an old school-chum of Urbahn’s, agreed to do it anyway. In the video, he plays himself (badly), interviewing Urbahn on a cheesy studio set. With a Number 1 and dressed down, Urbahn offers a whiff of warrior authenticity, although his identity is coyly withheld using optical and audio masking. Blue-screen graphics run continuously behind interviewer and interviewee, without rhyme or reason. Crysell starts off bad-cop abusive, but ends up thanking the artist for helping him with his inquiries. Urbahn’s testimony, cobbled together from text ripped from the Internet, outlines a parallel life of cult practices: kidnapping, murder, drugs, voodoo. But the testimony leaves us none the wiser. We never get to the bottom of it. Urbahn packages himself ambiguously, evading and digressing. Is he criminal, witness, or both? As inept TV, Lemon points to what might be at stake in the artist maintaining a properly professional image.

.

2001 Perv I used to adore the American TV show Infatuation. Wimps who didn’t have the guts to fess up to their objects of affection in private did so on prime time. Somehow, that made it easier for them—being buoyed along by the higher-stakes game, the prospect of being triumphant or trashed before millions. Or perhaps it just made it less real—they could fictionalise their drippy lovey-dovey feelings as simply playing the part. I remembered the show when I caught Urbahn’s video PS … I Love You at Wellington’s City Gallery. His idea was fiendishly simple. One Sunday afternoon, he stalked City Gallery Director Paula Savage, videotaping her every move. He started off peering at her in her backyard, from behind the shrubbery; he pursued her to a friend’s for brunch; he monitored her on a casual visit to the competition—Te Papa; from his car he cruised her as she ambled home down Oriental Parade, lovingly attending to her every wiggle. It was kind of creepy watching Savage go about her business mediated by Urbahn’s gaze. It was also amusing, because Savage seems such a benign target. Of course, the video wasn’t made for Urbahn’s getting off in private, but in public. By presenting his open love letter in Savage’s own gallery, he made a big show of his feelings and made her complicit. Was Savage simply a good sport, letting Urbahn show what he wanted, or was she flattered? Is this what a local artist needs to do to get a show? Was Urbahn, in fact, hiding his true love behind a conceit, his art strategy being a pretence to a pretence. Just like that old joke: my client may look insane, he may act insane, he may talk insane, but don’t be confused—he is insane.

.

2001 Ragpicker Archaeologists learnt much about how our most ancient ancestors lived by excavating their rubbish tips. For his exhibition Prole Art Threat, Urbahn delivered a trunk load of his own rubbish to the Anna Bibby Gallery and invited punters to sift. As centrepieces, he hung three blotter pads purloined from his WelTec drawing class. These multi-authored palimpsests of distracted doodles were, he thought, more telling, more artistic, than any of the coursework his decile-1 students had actually handed in. Into the mix of each cultural-blotter, Urbahn himself introduced a choice quote from an Internet blog site, applying scrag ends of Letraset in punky ransom-note style. One quote dealt with self-mutilation, one with alcoholism, the other with drugs. Around the blotters, he arranged all manner of detritus in zip-loc evidence bags, sticking them up with sexy black electrical tape. The hundred-odd baggies included bits of artworks that hadn’t made it off the drawing board, scraps of research material downloaded from the web, a candid snap of a weary Dame Cheryll Sotheran (twice Urbahn’s boss), and images of aliens. It looked like a detective’s mind map—or John Nash’s sticker board—but with the connections left for us to draw. A degenerate Killeen perhaps. Was the artist tracing the conspiracy or inventing it? As viewers, were we? Again Urbahn blurred the line between detective and suspect. If Prole Art Threat was less greatest hits than studio-floor sweepings, Urbahn’s work has always celebrated the excluded, the real, the grit that resists integration. His point of difference—throwing away the banana and eating the skin.

.

2003 Wicker Man In the movie The Blair Witch Project, students researching a legendary ghost find what they’re looking for. Hopelessly lost in the woods, they are stalked, terrorised, and ultimately slaughtered by shadowy forces. Given a zero special-effects budget, the filmmakers couldn’t afford to show much and had to resort to the power of suggestion. One of their best tricks was having the kids repeatedly encounter contrived arrangements of twigs hanging from trees. Clearly, these occult markers meant something, but, beyond that, the kids were out of the loop. I recalled this when I saw Urbahn’s obscure mock-ominous exhibition Trunk Rock. It was hard to know how to approach the works: as crude but intelligible signs or as exemplifying that mode of chaotic category-corroding phenomena George Bataille called ‘informe’ (formless). The show centred on three sculptures made of plaster and twigs. There was a model mountain studded with sticks; a seed-pod suspended on a chain, bursting open (it also suggested a meteor, or a spiky vulva); and a twig’n’plaster platform supporting clear marbles and tea candles, behind which a TV set screened a swirling psychedelic woodland scene accompanied by heavy-metal power chards. On the walls, Urbahn hung photos of sculptures in action. One showed another mountain-shape sculpture in darkness, illuminated only by fairy lights studding its surface—making it seem massive and sublime. Another offered alternate views of the pod—at rest and spinning hysterically, like Linda Blair’s head in The Exorcist. Trunk Rock was undoubtedly a dig at ‘twig art’. In the late 1970s, early 1980s, New Zealand art abounded with low-tech eco-art that typically celebrated some authentic Pakeha past—simpler times lived close to the earth. It was exemplified by the heal-the-world art of Andrew Drummond (whose penchant for folksy forked sticks advertised his sensitivity as a diviner) and hobbit-sculptor Chris Booth (who tied twigs long before becoming famous for stacking stones). But it wasn’t just a guy thing. Flicking through local art magazines of the day, it’s surprising how prevalent twig art was among the feminist set, with their goddess-worshipping ritual circles and menstrual moon dances. Trunk Rock taunts the holistic pretensions of such neo-paganism. If twig art was supposed to affirm us, nostalgically locating the believer at the centre of a harmonious world ruled by Gaia, Urbahn puts a bogus-bogan spin on it. Trunk Rock is his Deliverance.