Artforum, January 1998.

It’s hard to find someone with a good word to say for Te Papa, the new Museum of New Zealand, which opens on the Wellington waterfront on 14 February 1998. Created in a period of retrenchment in government funding, typified by welfare cuts and the selling-off of state-owned enterprises, this $NZ300M-plus museum is an anomaly. But, surprisingly, it’s not the price tag that’s the real sore point. For once, it’s the art lovers not just the taxpayers who are outraged.

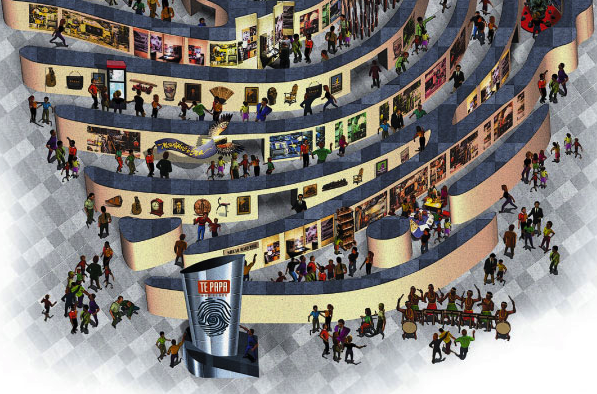

Back in the early 1980s, we were promised a new home for our lively National Art Gallery, then housed upstairs from the dismal National Museum. However, a change in government and stealthy lobbying saw this modest proposal picked up and turned around. In a complete about-face, the idea of a dedicated National Art Gallery was dropped in favour of a mega-meta-museum, a Museum of New Zealand, in which art would be just one of four cross-pollinating departments. Encompassing Maori culture, social history, the natural environment, and art, the museum would also embrace all New Zealanders, offering itself as a monument of national pride at a time when the social contract was coming completely unstuck. The museum would be something new—a populist, state-of-the-art infotainment centre, with all the bells and whistles that go with that territory.

Although New Zealand artists have been dodging the mandate of national identity for decades, Te Papa will essentially reinscribe our art as parochial social history—part of the fabric of our unique ‘material culture’. Art will be swallowed up by master narratives as works are reduced to artefacts or ciphers of social history. Notoriously, Colin McCahon’s breakthrough 1958 painting, the Northland Panels, will be exhibited beside an innovative refrigerator of similar vintage. Though contemporary artists have been recruited to create new artworks for the opening, the upcoming pieces sound more like museum displays. For instance, Lisa Reihana’s video installation addresses the identities of sitters in historical photographs, while Maureen Lander’s project references Maori string games.

Te Papa proudly combines New Right ‘dumbing down’—targeting the lowest common denominator, maximising ‘bums on seats’, offering fast-fix customer satisfaction—with a hyper-intellectual self-reflexivity about ‘museum practice’. Obsessed with its role as a cultural mediator, Te Papa seems to have lost track of the culture it is mediating, narcissistically confusing museum operations with the dynamics of the culture itself. At the same time, it has no opinion. It wants to be everything to everybody, to capture every niche market. Presenting its animatronics, its artificial earthquakes, and its do-it-yourself archaeology pit under the same roof as its treaties, meeting houses, and masterpieces, Te Papa’s postmodern collision of values offers little hope for art. The place will be full of art works, but bereft of art experiences.