Vault, no. 33, 2021.

.

In recent times, New Zealand artists have battled the tyranny of distance to join the great international-art adventure. The ground was hard won. Overseas study, international residencies, art fairs, and the Venice Biennale were key battle grounds, as our artists tweaked their strategic plans, honed their cover stories, and worked the room. This has become our recipe for international art-world success. So, when a mute, autistic, untrained artist in her sixties, based in Hamilton, and relatively unknown in her homeland, suddenly became an international success story, it was a surprise. She seemed to come from nowhere.

Like many in the New Zealand artworld, I first heard about Susan Te Kahurangi King in 2014, when New York magazine critic Jerry Saltz praised her work in the New York Outsider Art Fair, comparing her to Willem de Kooning, Jim Nutt, Roy Lichtenstein, and Carroll Dunham. ‘Much of her work could hold a museum wall next to these artists’ work’, he said.1 It seemed King had been on our doorstep for decades, under our noses, as we looked the other way.

.

Everyone who writes on Susan King must retell the story …

She was born in 1951 in the Waikato cow town of Te Aroha, the second oldest in a brood of a dozen kids. She’s Pākehā, but her parents, both Māori-language speakers, gave her a Māori name, meaning ‘treasured one’. At first, she was chatty, but, by the age of four or five, her ability to speak was in decline, and she would soon clam up entirely. Now, she hasn’t spoken for over half a century. Back then, there was little understanding of her condition, which is today listed as autism spectrum disorder. Some forty percent of autistic people are non-verbal.

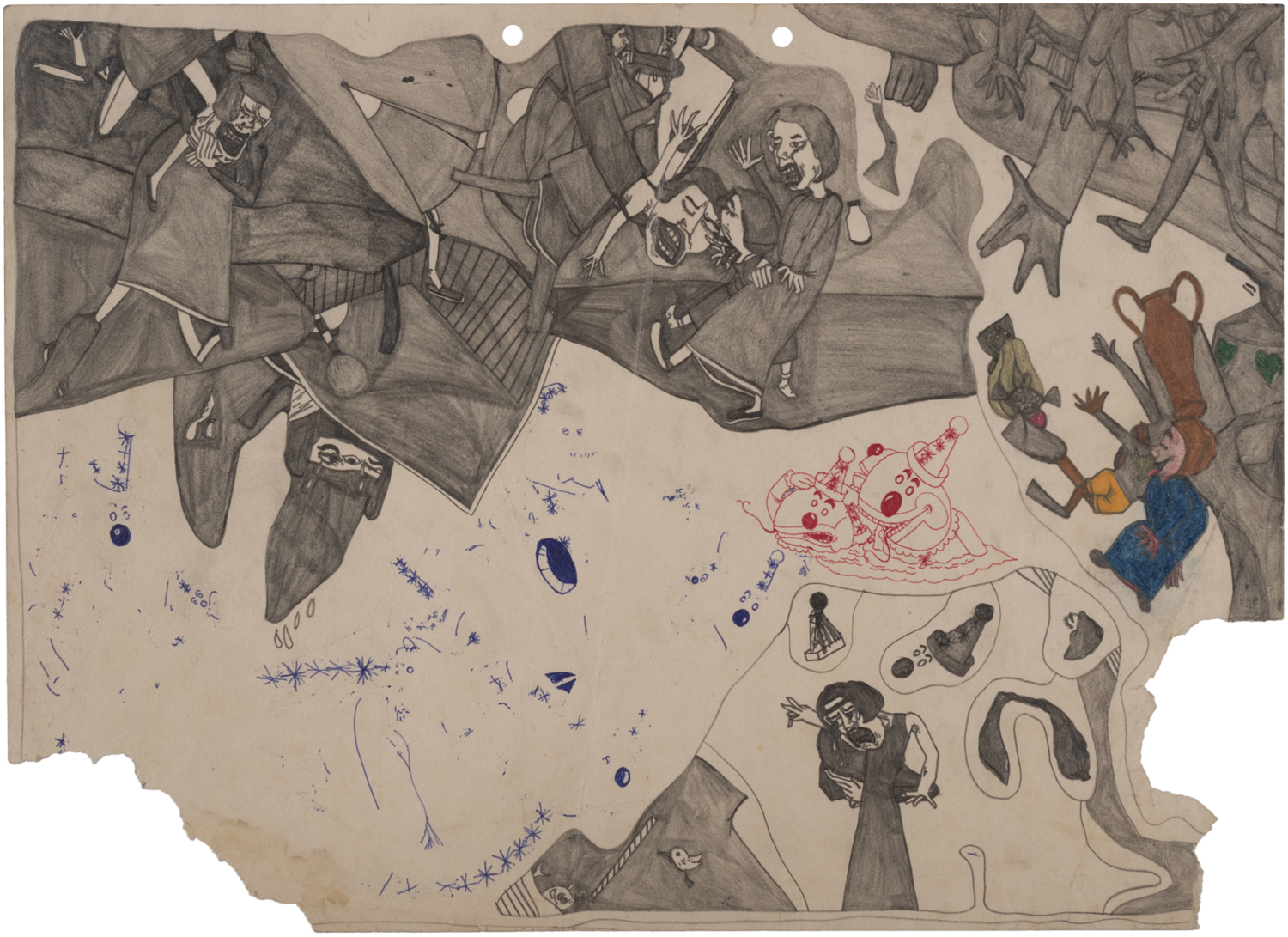

As a young child, King became subsumed by drawing, often for hours on end. Perhaps, once she stopped talking, it compensated for lack of social connection, giving her a different way to process her experiences. Her family loved comic books and animated cartoons—where animals take on human characteristics. These provided a source of inspiration early on. Her drawings often featured Donald Duck, Bugs Bunny, Foghorn Leghorn, Daffy Duck, and Co.—plus the Fanta clown from advertisements. There were also images from real life: people, animals (lots of birds), and other things. Her works became increasingly complex, culminating in densely patterned fields of fragmented, repeated imagery.

Not speaking was a problem. In 1958, King began boarding at Hamilton’s Christopher House, a school for intellectually handicapped kids. In 1960, the family moved to Auckland, so King could attend the Kingswood Centre, a special day school, where she remained for twenty-eight years. In 1965, she went under observation at Ward Ten, the mental-health unit at Auckland Hospital. During her stay, the nurses discouraged art activity, taking away pens and paper, hoping this might coax her out from her bubble. Similarly, at Christopher House, she also wasn’t allowed drawing materials, for fear other children might take them and draw on the walls. From 1980 to 1988, when she left Kingswood, there were lengthy periods when King didn’t draw at all, and she stopped entirely in the early 1990s for no apparent reason. Hundreds of her pictures were squirrelled away in boxes, bags, and cases, and some rolled up in the rafters.

Then, in 2008, not long before Dan Salmon began making his documentary about her art—Pictures of Susan (2012)—King spontaneously resumed drawing, picking up exactly where she had left off decades earlier. The following year, Sydney art collector and outsider-art enthusiast Peter Fay curated King’s first solo show off-off Broadway, at Callan Park Gallery—an outsider-art gallery in a former Sydney asylum. As word spread, King found champions in outsider-art curators, the New Zealander Stuart Shepherd and the American Chris Byrne, and in artists, including Americans Kaws and Gary Panter. King has since enjoyed a flurry of international shows in the United States and Europe, and is represented by dealers Andrew Edlin in New York and Robert Heald in Wellington. A monograph, The Drawings of Susan Te Kahurangi King, was published in 2016. Today, her work is in big collections, including the Museum of Modern Art and the American Folk Art Museum, in New York, and Philadelphia Museum of Art—but not Te Papa, not yet.

.

Early on, King’s drawings demonstrated immense flair and facility, invention and expression. They ranged. As Peter Fay observed, they’re ‘deeply disturbing, they’re funny, they’re hilarious, they’re taking the piss out of things. And they’re constantly in a state of flux and movement and change.’ She explores ‘all of the possibilities’.2

King played with how her figures are constructed and combined—Donald Duck got distorted and deconstructed. She took liberties with bodies, fragmenting them and shuffling the bits, or multiplying them (whole or in parts) and packing them together rhythmically like sardines in a tin, so they lost their individuality, becoming pattern. Sometimes, sets of images implied cinematic movement, flipbook style.

King was a magpie. Her art was diaristic, absorbing and processing the world she observed. Her sister, Petita Cole, recalls that, as a child, she seemed totally disengaged when attending a fair, but later incorporated detailed images of it into her drawings. Images of policemen, St John Ambulance staff, and the Queen appeared after attending annual Santa Parades and a 1970 royal visit. Images of Auckland’s new Harbour Bridge pop up here and there. A stylised head came from a logo on a local plywood supplier’s invoice.3 Random letter forms appear, often reversed left to right, spelling out nothing. Etcetera. King’s drawings are like flypaper, catching observations and impressions.

There’s so much graphic invention, variety, and nuance in King’s drawings, and there always seems to be something psychological at stake in their formal fun and games. Some are scenes, presenting figures within more-or-less spatially coherent settings. Some are pencil-case-art-style accumulations of heterogeneous imagery. Others emerge from the repetition of marks and forms, taking shape as stratified obsessive-compulsive crystals.

King plays with legibility and illegibility in games of hide and seek, with figures enfolded into one another and into their surroundings. Looking at her works demands shifting levels of attention, as we scan them to register the pattern, then again to excavate embedded images. Some works are jam packed, as if King had horror vacui—fear of blank space. And yet, other works leave half the sheet empty, as if this represented the air sucked out of the rest of the material, in the process of compressing it.

There’s often an emotional disconnect between subject and treatment. Works can seem idyllic or hellish, or both at once. Some suggest carnivalesque parties or demented orgies—there’s a libidinal dimension. There are a few penises, but no one seems to be having sex. King’s figures are not fucking but fucked up, with limbs tangled, multiplied, pressed together, and falling apart. Identity is fraught. Crying faces appear regularly, inexplicably. King clearly relates to the world of comics, where characters experience exaggerated emotions and suffer gruesome fates, only to pop back unscathed in the next frame.

King used whatever tools came to hand: graphite pencils and coloured pencils, ink pens, oil pastels, and crayons. And she used available pieces of paper, sometimes misshapen or already printed on. She coopted cyclostyled handouts from her father’s Māori language classes, drawing in the leftover space, apparently oblivious to the original inscriptions and their purpose, while oddly coexisting with them. And she drew on paste-up layout sheets, from his publishing job, playing on their ruled-up boxes as frames within frames.

King’s reputation has largely rested on the work she produced in the 1960s and 1970s—between the ages of ten and twenty-five. In her recent drawings—from this century—there is embedded imagery, but diaristic references are less prominent, leaving us with cellular, landscape-like, all-over abstractions, evenly filling the sheet. Candy coloured and decorative, these works recall stained glass or mosaic. This was the direction in which King’s work had already started moving when she stopped drawing in the early 1990s.

.

Critics routinely name check canonical artists King would not have known, but that her works nevertheless seem to speak to. In the early days, her comics connection was limited to mainstream G-rated Disney comics and Looney Tunes shorts. She wouldn’t have known underground comix, which were contemporaneous with her work, or their precursors, like Winsor McCay’s proto-psychedelic newspaper comic Little Nemo in Slumberland, yet they are birds of a feather.4 (American cartoonist Gary Panter compared some of her work to a bad acid trips, but I doubt she enjoyed access to class-A drugs.)5 King wouldn’t have seen much art either. Her repeated, deconstructed figures recall Marcel Duchamp’s cubist joke, Nude Descending a Staircase No. 2 (1912)—and, more so, Peter Saul’s pop parody of it, Donald Duck Descending a Staircase (1979). Her works shout out to the pop artists and the Chicago imagists, and to Philip Guston’s comic accumulations of legs from the 1970s. The way her characters dissolve into pattern evoke the insane dotty obliterations of Yayoi Kusama, the most inside of outsider artists. Closer to home, some of her works anticipate the gimps and speed-freak perspectives of Bill Hammond’s 1980s paintings. And so on. Like finding an airplane buried under the pyramids, they prompt us to rethink art history, to double check the dates.6

.

Outsider artists—indeed, all artists—need a story, a hook, a point of difference. King’s is that she doesn’t speak, that her words dried up. But, in itself, this hardly explains her works, which would be just as remarkable if she did speak. Some say that art is her means of communication, assuming her works are attempting to tell us something. But, perhaps they are a solipsistic activity, addressed to no one but herself. Either way, we are left revelling at her formal inventiveness while grasping at straws interpretively, drawing our own conclusions. This, of course, only sharpens the work’s enigmatic appeal—like a club that won’t have us as a member. As Cole concedes, ‘a lot of this stuff we will never know’.7

Today, outsider art enjoys a growing audience and is increasingly shown with insider art. It appeals to a jaded art world, for its sincerity, its authenticity, its lack of strategy—for being made out of internal compulsion, rather than for audience or market, fame or fortune. Italian curator Massimiliano Gioni famously integrated insiders and outsiders in his show The Encyclopaedic Palace—the centrepiece of the 2013 iteration of the Venice Biennale, the mainstream art world’s most important networking event—disrupting and enlarging the story of art. If outsiders can be part of the curated show, it begs a question: could King ever represent New Zealand at Venice?

There’s certainly enough artworld interest to make that succeed and King’s story is compelling. But, if she was selected, it would certainly break our mould. To date, New Zealand’s idea of a national representative is an insider—an artist player, a product of the system (art school, markets, museums), who can propose a new attention-grabbing step-up project requiring six-figure investment. We pick an artist with global ambitions; an artist who wants the opportunity and can say so; an artist who can bend the ears of patrons, their teams, and the media at home and abroad. In short, an artist who talks.

Susan King remains poker faced, leaving her art to ‘speak for itself’ … with a little help from its friends.

.

[IMAGE: Susan King Untitled c.1966–70]

.

- Jerry Saltz, ‘Seeing Out Loud: The Best Things I Saw at Frieze New York and the Outsider Art Fair’, New York, 13 May 2014, www.vulture.com/2014/05/saltz-the-best-of-the-frieze-and-outsider-fairs.html.

- Dir. Dan Salmon, Pictures of Susan, Octopus Pictures, 2012.

- See Drawing the Inside Out: The Art of Susan King, https://vimeo.com/281387315. For insights into King’s sources, consult Petita Cole’s Instagram account, The Petita Cole Collection: Memorabilia Items I’ve Collected that Relate to the Life and Works of My Sister, Susan Te Kahurangi King, www.instagram.com/thepetitacolecollection/.

- Long before the pop artists got their hands on it, much mainstream American comics culture—including Looney Tunes—was full of the formal experimentation and self referencing that also typified avantgarde art. See J. Hoberman, ‘Vulgar Modernism’, Artforum, February 1982: 71–6.

- Gary Panter, ‘Looking Inside’, in The Drawings of Susan Te Kahurangi King (Miami: Institute of Contemporary Art, 2016), p 19.

- Other writers have their own lists. Tina Kulielski, for example, name checks Öyvind Fahlström, Ray Yoshida, Christina Ramberg, Sue Williams, and Joyce Pensato. Tina Kulielski, ‘Pantomime Strip: Susan Te Kahurangi King’s Exploration in the Extra-Human’, in The Drawings of Susan Te Kahurangi King, 11–7.

- Pictures of Susan.