Being Seeing Making Thinking: Fifty Years of the Chartwell Project (Auckland: Chartwell Trust and Auckland Art Gallery, 2025).

_

Susan Te Kahurangi King’s story is now well known. Born in 1951, her powers of speech dried up in her early years and she never learnt to read or write. However, she did begin drawing, prodigiously. Endlessly inventive, her drawings incorporated things she experienced, famously including comic-book characters and animals, logos and landmarks, and household items. King distorted, deconstructed, and dissolved her subjects, sometimes transforming them into psychedelic patterns.

While comics were an early source and inspiration, King had a skewed relation to them. She couldn’t read their text parts, so effectively ‘lost the plot’. This left her immersed in and attuned to their pictorial conventions, which most of us overlook when reading for the story. Her prolific, fascinating output stems from such an odd conflation of incomprehension and virtuosity, deficit and gift.

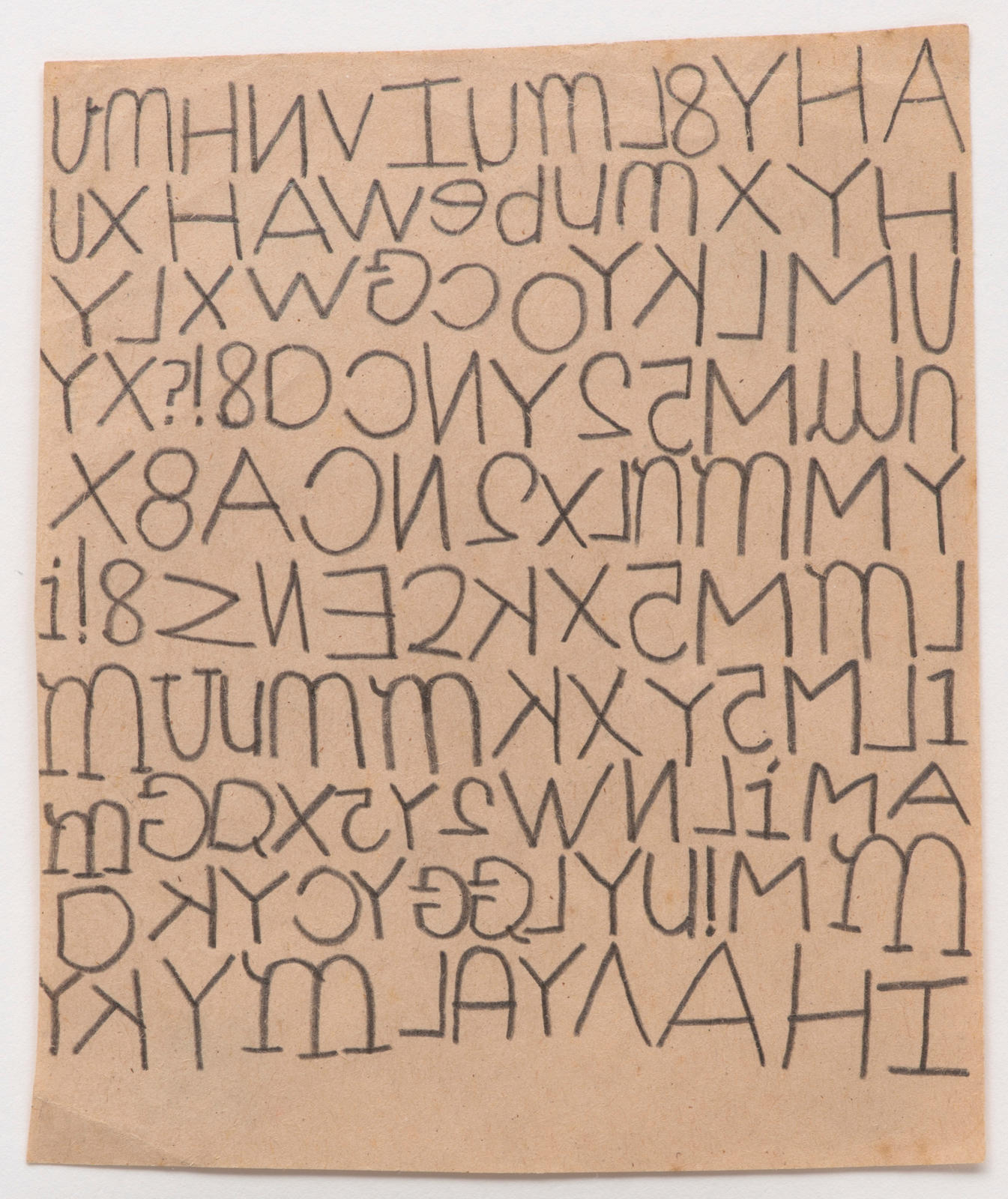

In Chartwell’s Untitled (c.1965–c.1970), there’s no comic-book imagery, no images at all. Instead, there’s language. Letters, numbers, and punctuation marks are printed in pencil, in bold simple strokes, line by line, more or less filling the page. Some are upper case, some lower; some serif, some sans; some right way around, others reversed, inverted, incomplete. Who knows if she is intentionally messing with the letters’ shapes or if she thinks it’s how they are? Perhaps she’s pursuing a jazzy, rhythmic, decorative effect, like some antipodean Paul Klee.

Lettering regularly appears in King’s work, usually as accumulations of random letters, sometimes hidden or camouflaged. In addition to hand-drawn lettering, King has used stencils and rubber stamps. Other glyphs turn up: dollar signs, peace signs, musical notes. On rare occasions, a recognisable word appears—a Gestetner logo or a comic-book knockout ‘POOF’. Sometimes scribble suggests handwriting or blocks of text. In other works, she has incorporated—or worked around—text already on the miscellaneous sheets she’s found to draw on.

As you are reading this, you have a very different relation to text to King. She doesn’t know the letters’ names or the sounds they represent, let alone what words mean. For her, letters are signifiers adrift from their signifieds. In everyday life, when she’s required to write something, someone else writes it out for her to carefully copy. Even when she does this, she often reverses or inverts letters, deletes or doubles them. Is this intentional or unintentional, wilful or neurological?

With the Chartwell drawing, we might imagine that something meaningful lurks behind King’s inscrutable curtain of rendom language, as with the Rosetta Stone or the cascading code of The Matrix. We might be tempted to scour it for embedded words or to try reading it aloud, like a dada sound poem. However, it seems more likely that King is drawing letter shapes because she’s intrigued by them graphically, without understanding them. It’s not to do with conveying or concealing some message.

Letters may be the basic building blocks of communication that connect the rest of us to one another and the world. We take them for granted, as tools, as means to an end, but, for King, they are toys to play with, ends in themselves.

[IMAGE: Susan King Untitled c.1975–80]