Bambury Works, ex. cat. (Wellington: City Gallery Wellington, 2000).

Robert Leonard interviews Stephen Bambury.

.

Robert Leonard: The show’s non-chronological hang lets works produced over twenty-five years participate in the same notional moment, as though they all remain relevant and live and equal, as though new arguments hadn’t succeeded old ones.

.

Stephen Bambury: The show offered me the chance to circle back and collect some initiatives from long ago, things I haven’t looked at in ages, things which have never or barely been exhibited. Wystan Curnow, the curator, recognised that my work doesn’t develop from beginning to middle to end, and we carried that idea through with the show, configuring it without any sort of chronology, which is unusual for a retrospective. We were thinking a lot about the shift that comes with postmodernism; making abstraction seem no longer simply about intrinsic formal properties but also about extrinsic aspects, the life of the work in relation to places and moments, languages, discourses and histories.

.

So, this show places early formalist works within the context of your more recent post-formalist project.

.

Looking back, I’m approaching my early paintings as something of a stranger, they feel as if someone else did them. Mel Bochner says all works are consciousness viewed from the outside, but now I’ve got so much time on them that it sometimes feels like someone else’s consciousness. In the early days, I was trying to fit certain agendas, but, in retrospect, it interests me how the work often failed to meet those agendas. Now, I’m more interested in the failure than the success, and in the peripheral content, the stuff around the edges. For example, Tetragonal Black, the earliest work in the show. In 1975, it was about disrupting the consistency of the grid, now it seems more about movement, the red moving into the black, sliding into place or out of it.

.

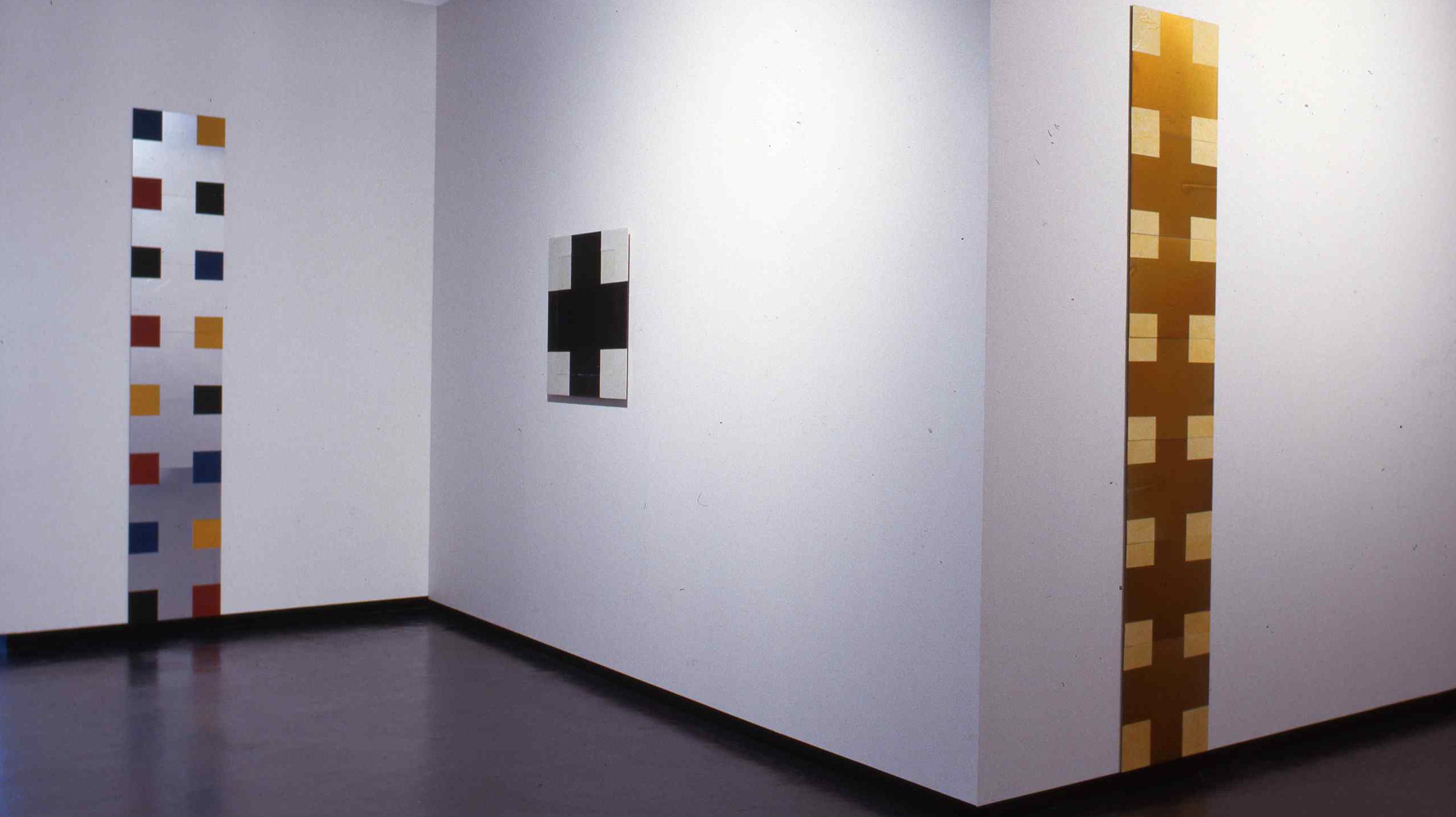

The work changes in the late 1980s. Before then, you’re moving along in a logical progression, as with a philosophical inquiry or experiment. Then in the late 1980s, there’s a rupture. The work takes on a different logic. Once you hit the crosses, it’s less about progressing an idea, more about elaborating one, expanding on it, multiplying it, detailing it. You become fixated, yet expansive like never before.

.

It’s like there are two mes, one up to the late 1980s and one following. Early on, the work seemed more about essence and purity, about radicality, progress and a desire for historical closure. The usual stuff. I got fairly close to the monochrome thing, but I got dissatisfied with the dogmatism involved. I see now I was already uncomfortable with formalism. And, while the work might have appeared to be operating within minimalist and formalist conventions, I was never trying to ‘evacuate content’, to use your term. As I look back, I see I was always increasingly bringing content on board. Coming to terms with postmodernism was really what did it. Going to Melbourne in 1987 for that residency was crucial. I got to meet the artists who became the core group at Store 5, Kerrie Poliness and Co. John Nixon was a key figure. I was so relieved, because I found it hard to relate to the abstract work in New Zealand at the time, which was British, in a 1950s kind of way. The Australian work was so different. It was fresh, energetic. It was about letting stuff in rather than locking it out. It had attitude. They ran their interest in the historical avantgarde through a set of postmodernist filters, which generated a whole different discussion. It was conceptual painting, and it gave me ideas about how to open up my own practice, about raking through the embers of the prematurely liquidated modernist project. There were many things about modernism I didn’t want to abandon, and then there was a lot I did.

.

How did this relate to the New Zealand situation?

.

Right through into the 1980s in New Zealand, there was this belated battle for the high moral ground between internationalism and nationalism (or provincialism, as some called it). At some point, I had this idea that there might be a space between these positions, and that that might be where the action was. It was like cutting a Gordian knot, the idea of saying no to both arguments, or yes to both. Courting duplicity. And while the work seemed to retain its former autonomy, it increasingly leaked into something more discursive and contextual. I like the idea of the work existing formally and post-formally at once, being both hermetic and porous. I aim for that equivocation. I’m not prepared to buy into a position with some sort of consistency. There is a consistency, but it’s a consistency that emerges out of the production itself.

.

Ngamotu?

.

I made it for the Govett-Brewster in 1993. It’s a floor painting, a chakra made of seven trays; seven crosses filled with crude oil and the squares between with water. Ngamotu, meaning ‘islands’, is the Maori name for a New Plymouth beach. It’s where oil was first discovered in New Zealand. I was a little apprehensive about using a Maori placename—at the time, Gordon Walters was being rapped on the knuckles for his appropriations. But when Aunty Marge, the gallery kuia, came in to check out the piece, I told her my idea for the title and she got it instantly, and she said, ‘Around here, oil and water don’t mix.’ So I went with it. Certainly, New Plymouth is a site of plunder and asset stripping, and of passive resistance—Parihaka. And those ideas are still current; those actions are still being played out. The piece combined oil, which has sustained the local economy, and water, which is essential for life, arranged in a fragile state of co-existence, providing an image of transcendence that might or might not be available through this path of contamination. For the installation here at the City Gallery we opened the shutters over the windows. Those reflections are great. The work lets the world in.

.

I’m intrigued by the way the cross works appear so flat, but have this subtle spatial dynamic going on.

.

My work’s never been about the kind of flatness that modernism is supposed to have aspired to. It never interested me. It’s more about where pre-renaissance painting links up with suprematism. In the renaissance, everything is pulled back to a central vanishing point, making the viewer God. But in pre-renaissance painting the spaces are incoherent, at least from a renaissance point of view. But if you move around in front of those paintings, there are multiple points of perspectival convergence, and from different points things that appeared spatially wonky start to cohere into some kind of sensible framework. Now, the viewer isn’t God; the centre of the world is somewhere else. Pre-renaissance painting, with its weird perspectives, is often cast as an unresolved version of renaissance painting, but, really, it’s offering a completely different proposition; it has more in common with Indian miniature painting. And that sense of perspective is echoed again in suprematism, with Malevich’s tilted cross and his not-square square. So, while, at first, the shapes seem to belong to the flat surface, when you spend time with them they open up into a space beyond, a shallow infinity.

.

You hung Chakra in a specially constructed corridor, encouraging people to view it up close while walking past.

.

It’s like McCahon’s idea of ‘paintings to walk by’. And when you walk by, it does odd things. The repetition of the crosses causes a sort of cinematic flickering, a pulse. Actually, Wystan sees those early double-frame ones as cinematic in a different way, as empty screens awaiting projection; so there there’s less a sense of dynamism than of anticipation, of time-before. I’m interested in all those temporal qualities. Chakra is not only cinematic, or kinematic, it’s also photographic. The panels look like inconsistently processed blank film frames. The image comes from inconsistencies in the processing, especially when there’s a group of similar panels run together. I court that. It’s that kind of ‘process marking’ I do. The panels are processed or treated rather than painted. They’re obviously hand-done but it’s not an autobiographical mark at all.

.

Icon painting was always a production-line affair. Baudrillard writes about the spiritual as an effect that can be generated mechanically.

.

But some icons have real power and others don’t.

.

Baudrillard deconstructs the opposition of iconoclasm and iconolation. He says the iconoclasts were the truer believers because they invested in the power of images enough to need to destroy them, and that the iconolators were truly modern because they invested in the mechanistic nature of imagery, its ability to generate a divinity with nothing behind it.

.

That feels right. Malevich certainly was a believer, that’s evident in the intensity of his iconoclasm. For his suprematist work, he took what he needed from the rhetoric of Greek orthodox icon painting, for instance the traditional placement of the Russian icon high in the corner of the house. He exploits the register of the icon as a meditative object, while appearing to jettison so much of the tradition, the gold, the figurative. Iconolation and iconoclasm are both there in the suprematist work, revving one another up. The iconoclastic dimension is really testament to his belief; his not mine. I’m no iconoclast. Implicit in iconoclasm is transgression, and I’m not really interested in transgression. I agree with Herzog and De Meuron, who say it’s boring not to be normal today.

.

Where did the Ideogram paintings come from?

.

The idea first appears in my notebooks in Paris in about 1991. Initially it was going to be just ‘HI’, done in a quasi–de-stijl manner. I was going to call it Friendly Abstract Painting. The idea lay dormant until I came back to New Zealand and was offered a large commission for a wall with three speakers built into it. I wanted to avoid this wall because of those speakers, but the clients were adamant; this was the wall they wanted the piece for. Then I got really interested in the idea of these speakers. I’d been thinking about McCahon’s Angels and Bed works, which include those speaker shapes, particularly his painting Hi-Fi. I found myself wanting to turn his Hi-Fi inside out, taking the little title inscription from the bottom margin of the painting and making it the whole painting, and then leave those speakers on the wall around it. I’m into aspects of McCahon’s work that have been ignored, things that aren’t obvious, that are buried. The Ideograms became a ‘what if’ situation: what if this overlooked detail were the major aspect of the work? What if I dovetailed this slice of McCahon with my interest in the ideogram and the form of the I Ching?

.

Because the ideogram is the combination of abstract form and language?

.

Which all abstraction is anyhow. The work is emblematic of the moment I first profoundly felt modernism enter my life. It was as a kid in the mid-1960s, when the first swish stereo cabinet came into the house and we got a test record. Sitting in the lounge and hearing the train come through one wall and go out the other was a big moment. For me the transpersonal narrative of modernism and the story of my own personal engagement with it collapse into one in this work. The Ideogram in the show is actually the second version, and in a sense turns the first inside out. Everything that’s hard and rigid and permanent in the first becomes soft and dematerialised and provisional here. In the first, the panels are hard-pressed and abutted, pristine and crisp; here, they’re soft and stitched together. The first sits just two or three millimetres off the wall, but this one sits on chocks, in an ambivalent space between the wall and the floor, between the gallery and the storeroom. The first is permanently installed, but the second … you’re not sure if it’s about to be installed or about to go into storage. That kind of transience and mobility gives it a different sense.

.

High fidelity literally means obedience to truth.

.

Wondering is really the point. Hopefully the work opens up a space for contemplative wondering. Certainly, as a child, going from mono to high fidelity inspired awe and disbelief. Like, ‘I can’t believe it, the cymbal’s shimmering over there, and the bass is over here!’ It’s magical, that sense of disbelief. There’s something about the idea of hi-fi that takes us beyond our normal range of expectations—a train passing through the living room. As a kid, experiencing that, it was very powerful. As an adult, I would just see it as a trick.

.

The Copper House?

.

The house shape comes out of a post-suprematist Malevich drawing. Many people ignore this highly fertile period of Malevich’s work. Malevich’s work after suprematism is an embarrassment for some people, as if going back to the figure were necessarily and demonstrably the failure of abstraction. That’s so simplistic. Much of the development of the post-suprematist work is concurrent with the suprematist work. Anyway, I find this period of Malevich’s thinking fascinating and that drawing is a very curious thing. There’s the horizon line he often draws in, and a figure, and you can’t really tell whether the figure is looking out or in, facing you or facing in. In what appears to be a space behind the figure but in front of the horizon, there’s this cross. And, in the foreground, there’s a very tiny little house form. Well, it’s either a house or a grave, either way it’s a house. It’s such an open-ended and paradoxical image. It captured me.

.

Is Malevich’s house split in two?

.

Not at all. But in my work it’s not ‘split’ either, there’s no violence, no rupture; it’s more an opening. You’re invited in. Nearly all my works involve reflected forms. The works mirror themselves: left/right, top/bottom. The dual, the doubled, is a constant in the work.

.

And it’s church-like.

.

You say ‘church’, I say ‘contemplative’. When I get to visit the great gothic cathedrals, I don’t thank God. I thank the architect, and that’s the difference. I should footnote Judd there, he said it first.

.

The companion work, Golden House, has a strong Necessary Protection association, that ‘light falling through a dark land’ thing.

.

You talk of McCahon, but I also want to evoke Barnett Newman’s Cathedral. Of course, McCahon looked very hard at Newman. I find that cross-referencing a fertile area. Really, I don’t want to see McCahon in isolation as tends to be the way here. That’s my ‘Necessary Correction.’

.

But you’ve drawn on McCahon a lot in recent times.

.

In 1991, I came back after three years in Europe knowing that McCahon was a huge asset for me here in a way that virtually nothing else was. Looking back I can see that McCahon’s voice inflects my work right through. McCahon’s part of my cultural landscape, part of our cultural landscape, but still only part.

.

You say McCahon inflects the work ‘right through’, but back in the late 1970s I can’t imaging you saying that.

.

Sure. Back then, he was the enemy. The work was used to exemplify an argument I opposed and so I was opposed to McCahon. But that positioning was really false. It wasn’t a matter of what McCahon was for but what the culture said he was for. McCahon was somewhere else. He was an astute reader of international art, all art, yet you had this official programme of reception mounted against that, against his classically modernist project of synthesis. McCahon really came into my thinking through the back door, it was the perversity of his homage to Mondrian—saying thanks but using that heretical diagonal. McCahon pushes things so far through his wilful misreadings that the work takes on an almost proto-postmodernist quality. He provides a model for making use of the tradition, escaping it, and feeding into it at once. And that’s the only way the discussion can move forward. I see a lot of very sterile uses of McCahon, which I’m not really interested in.

.

Let’s close on the most recent painting in the show, The Golden Echo (for Wystan). I’m used to your works having figure-ground relationships which are managed, controlled, precise; and being painted in a way that is very considered. So this one’s a real surprise. I don’t know whether I like it or not. The paint is almost sexual, secreted. There’s a vulgar, foody, super-sweet but abject quality to it, like sticky icing.

.

That work certainly is loose. I’ve become keen on having the forms juddering right across the boundaries people are expecting them to fit into, deranging any orthodoxies I appear to have been setting up. Here, there’s a real sense of the elements not quite being in place, but good enough! I’ve always wanted the work to fly apart, from a very centred position. I’m surprised by your choice of words, because I find it quite ravishing. I want to go there.