Shane Cotton: The Hanging Sky (Christchurch: Christchurch Art Gallery, in association with Institute of Modern Art, Brisbane, 2013).

In 2003, Shane Cotton’s big exhibition at Wellington’s City Gallery was in two minds. The gallery wanted a curated show with all the key works, summarising Cotton’s development, explicating his imagery, themes, politics, and achievement. But Cotton didn’t want the museum-retrospective treatment. He wanted to do a ‘project’ show of new work. Museum and artist both got their way. Downstairs, curator Lara Strongman assembled a tight, greatest-hits selection of Cotton’s works from the previous decade. Upstairs, Cotton presented a cycle of seven large diptychs that were wildly new in imagery and treatment. The show felt like two shows in counterpoint, as if two artists were being presented: downstairs, the Cotton the gallery and ‘the culture’ expected, even demanded; and upstairs, the Cotton Cotton wanted. You could take your pick, or compare and contrast.

In retrospect, the show’s polarised quality seems symptomatic of a dilemma Cotton faced. In the ten years since his 1993 breakthrough show at Wellington’s Hamish McKay Gallery, Cotton had tapped the biculturalism zeitgeist, becoming a key figure in the paradigm-shifting ‘new generation’ of Maori artists that Jonathan Mane-Wheoki would call ‘the young guns’.1 Feted by curators and collectors alike, Cotton seemed to tick all the boxes: as much as his work was rooted in local history, it also offered a new spin on the most current of international art concerns (appropriation). However, being typecast as an ambassador for Maori causes proved to be something of a trap for this artist, still in his thirties. Prevailing cultural politics were overdetermining readings of his work, casting it as illustration and instruction, and bypassing the exploratory, speculative nature of his practice as a painter. By 2003, Cotton was no longer riding the waves of biculturalism, they were riding him.

While the downstairs part of the City Gallery show locked Cotton into a pious and by now familiar discourse about history, place, and identity, the diptychs upstairs, with their pop-art quality, were unexpected. Style and imagery felt utterly experimental. Riffing on their place in Maori lore, birds suggested harbingers of death, emissaries from the beyond, intercessors between earth and the heavens—‘translators’, Cotton called them. Meanwhile, bull’s-eyes recalled archery targets and Royal Air Force insignia—although Cotton said he saw them more abstractly, as vortexes. Their juxtaposition seemed visually vital, yet fatalistic. But, given the cultural anxiety surrounding them, Cotton’s images of toi moko (Maori preserved heads) were far more morbid and provocative.

Preserving heads dates back to pre-contact times. Maori kept the heads of important men who had died, from their own tribe (to venerate) and from vanquished enemy tribes (to lord over). However, following contact, toi moko became curios, trophies, ornaments for the Pakeha—tourist art. During the intertribal Musket Wars, slaves were tattooed and killed so their heads could be traded with Pakeha for guns and ammunition—these heads are known as mokomokai. Having never previously been tattooed, slaves were now inscribed carelessly with a ‘jumble of meaningless motifs’, contributing to the desacralisation of the moko and its decline as a status symbol and art form.2 Fast-forward to the 1990s and toi moko have become a sore point. On the one hand, Maori condemn museums for their insensitivity in continuing to display their tapu heads and petition them to repatriate these ancestral remains to relevant iwi. On the other hand, the same heads are also evidence of indigenous brutality, Maori insensitivity to their own ‘cultural values’, and shamefully at odds with popular feel-good representations of the tangata whenua as children of nature and noble victims.

Presented repeatedly, frontally and in profile, Cotton’s toi moko took on a cut-and-paste, decal-like quality. His heads were not exactly tattooed: some were camouflage-patterned or rainbow-striped. The camo-heads seemed to nod at once to military fashion and to Andy Warhol’s camp 1986 pop-goth self-portraits, in which Warhol superimposed camo-patterns over an image of his own disembodied, white-wigged, toothless, pasty face. (Interestingly, he died the following year.) But, what was at stake in Cotton subjecting toi moko to Yellow Submarine or Warholian graphic treatment? Was this some somewhere-over-the-rainbow redemption of the heads, or blithe disregard to their sensitive nature—insult added to injury? Was Cotton pointing to a problem or a solution? Whose side was he on?

Although Maori references permeated the new work, Cotton seemed to have largely dispensed with customary Maori stylisations; his birds could have been lifted from an encyclopedia. His images were not organised on trees, feast scaffolds, or shelves, or integrated into bold emblems, as they had been previously. Now, they were more like tokens, provisionally placed on flat black void-fields and spray-painted skies, less organised than disorganised—lost in space. Cotton’s diptychs were inscrutable, cryptic. Sure, his earlier works had dispatched critics and curators to the library to double-check the citations and to brush up on their history and their Maori language, but the diptychs were beyond obscure, they were positively deranging. They begged for interpretation, but defied it. They made you wonder not only if you understood what Cotton was doing now but whether you had even understood what he had been doing before. As much as the diptychs could be seen as continuing Cotton’s previous concerns, they could also be read as a dummy spit, with Cotton shrugging off the worthy expectations weighing down on him and cutting himself some slack.

With the diptychs, a surrealism previously implicit in Cotton’s work had suddenly become explicit and urgent. Now Cotton was clearly not being prescriptive or normative—making ‘signs and symbols for people to live by’, as Colin McCahon had put it3—but was free-associating with images, crashing together Maori and Pakeha image fragments in the manner of Lautréamont’s notorious ‘chance encounter on a dissecting table of a sewing machine and an umbrella’.4 If the surrealists had clashed codes to explore the repressed, unfinished business of the psychosexual unconscious, Cotton was doing the same with the post-colonial historical and cultural unconscious. The surrealists had been disinclined to analyse the latent content of unconscious imagery, preferring to bask in its manifest poetry—its non-sense. Where psychoanalysis sought to heal the patient in order to reintegrate them into society, surrealism declared society itself sick and their unconscious, automatic imagery a revolt against it. So, perhaps at this point, the idea that Cotton was advocating some ‘sane’ bicultural reconciliation should have gone by the wayside.

In the years that followed the City Gallery show, Cotton would continue to explore the directions opened up by his 2003 diptychs, refining and expanding his speculative cultural-surrealist approach. With his increasingly acrobatic, reckless, even suicidal birds, he took to the skies, largely leaving the land (and any safe hermeneutic footing) behind.

•

In 2011, Cotton acknowledged the influence of the surrealists in titling his Hamish McKay Gallery show The Treachery of Images. Cotton borrowed this title from Rene Magritte’s famous 1928–9 painting of a pipe that is not a pipe.5 Cotton’s work owes much to the Belgian surrealist. The links to Magritte are obvious in Cotton’s endless plays of substitution and displacement, in his disorienting and illogical scale shifts, in his puzzling mismarriages of images and idioms, in his penchant for frames and frames-within-frames, and in his witty title play. Both artists exploit chains of association and analogy within works and between works, making interpretation interminable, postponing closure. Their puzzle pictures foreground the machinery of representation while transporting us into poetic other worlds.

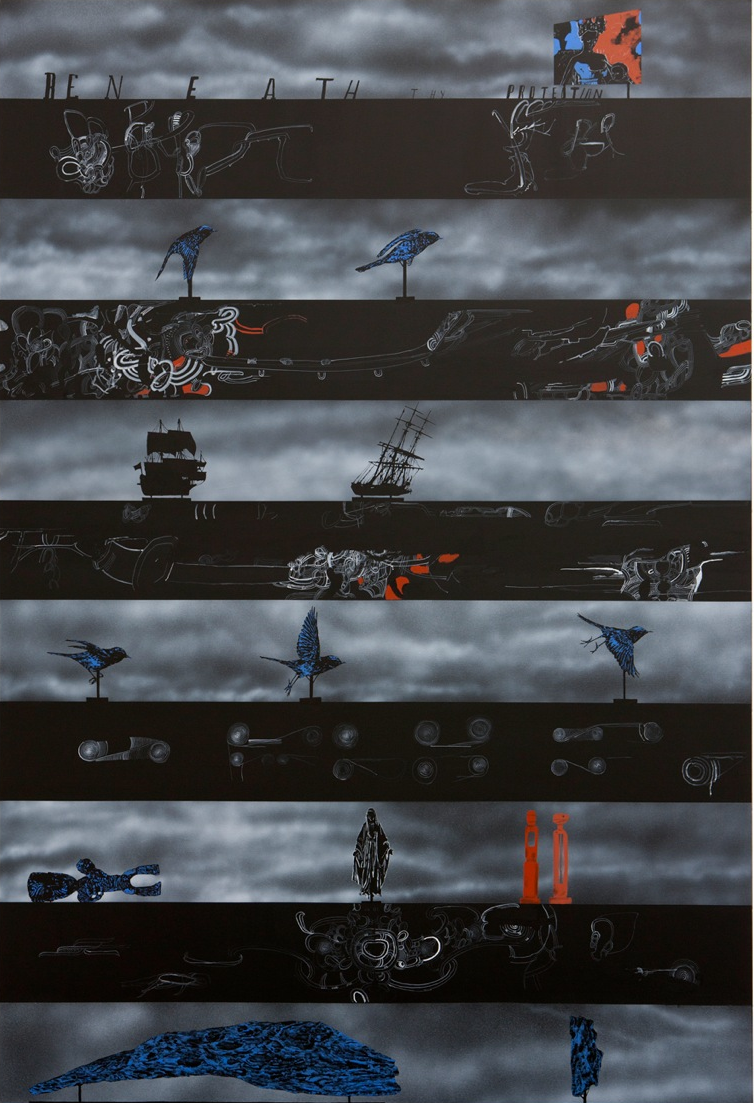

Magritte keeps it simple; in each work, he tends to isolate a single trope, to tease out a particular ambiguity. Cotton, by contrast, prefers complexity, hybridity, and excess. Consider Back Words (2011), from Cotton’s Treachery show. The painting is divided into eleven horizontal sections: flat black bands inscribed with scribbly Maori spirals alternate with deep spray-painted skyscapes that provide backgrounds for exhibits. These exhibits include stuffed birds on stands, dead, yet frozen in different stages of flight (recalling Eadweard Muybridge’s animal-locomotion studies); tall ships, the same size as the birds and also on stands; a billboard (or is it a drive-in movie screen?); that famous Maori carving from the 1840s of a mokoed Madonna and Child (now in the Auckland Museum), toppled;6 a Western-style Madonna sculpture; two red Arnold Wilsonesque Maori-modernist sculptures; and a couple of blue pitted rocks, also on museum stands (are they pebbles or asteroids?). There are also some freestanding letters, which recall both Colin McCahon’s text paintings and the Hollywood sign; they spell out the title of a Christian hymn ‘Beneath Thy Protection’. (If this derelict signage acknowledges a caring God, it seems to be one who has left the building.)7

Not only does Cotton mix imagery here, he also scrambles styles and idioms. References to printing, painting, Maori carving, Western sculpture, model ships, moko, kowhaiwhai, hymns, and taxidermy collide. The silhouetted ships look like shadow puppets, while the birds and stones are painted to look like they were printed old-school style, with black-and-white ‘line work’ filled in with solid ‘spot colour’. The way the skyscapes are stacked recalls McCahon’s serial landscapes. They could represent sections of a continuous scene or different places and/or times (a history, a narrative)—or not. One can only ponder the relationship between the skyscapes and the inscribed black bands that insulate and link them. Are we to understand those bands as labels or shelves, supporting and distinguishing the exhibits above them? In relation to the skyscapes, are we to read the inscriptions on the black bands as source, translation, crib, or critique?

In Cotton’s works, images seem sometimes to belong to obscure or obsolete frameworks, sometimes to exist in-between various frameworks, and sometimes to have come adrift from any framework whatsoever. Adding a twist to Magritte, Cotton exploits the ways that images can move in and out of plural, even antagonistic, cultural value systems, connecting and disconnecting with alternative signifieds. This idea informed a suite of painted baseball bats that Cotton also included in his Treachery show (perhaps intending to recall the way Magritte had painted on phallic objects—rendering nudes and clouds on bottles).8 While the bats suggest partisan politics, the need to take sides in conflicts, be they sporting or violent, these ‘sides’ are not explicit. On the bats, Cotton painted his characteristic mélange of historical and contemporary, Maori and Pakeha imagery. One bat features an image of the Maori Madonna and Child carving. Is Cotton suggesting that such images—and the ideologies they refer to—are symbolic weapons, which might do violence upon us (or for us) without touching us? Or is he suggesting that those images are actually frail and endangered, for one would surely not swing the bats for fear of damaging their exquisite surfaces?9 Similarly, as much as Cotton’s line of bats suggests an arsenal, implying we might take our turn to pick one up in defence of the realm, they also suggest a colonial-history museum display of pathetic, retired spoils of war. Perhaps these conflicted bats are at war with themselves.

To an audience anxious for answers, Cotton offers allegorical impasses and frustrating interpretive feedback loops. His works radiate an enigmatic quality, like yet-to-be-deciphered Rosetta Stones. Cotton piles language upon language, reference upon reference, trope upon trope, scrambling different modes of representation, offering too many clues (and perhaps a few red herrings), generating cross-cultural moiré patterns. There are simply too many, contradictory ways to read his works, so that any clear interpretation seems wishful. There’s no advocacy here—confusion reigns. Cotton’s pictorial imbroglios recall the awesome snowballing wreckage famously contemplated by Walter Benjamin’s ‘angel of history’: ‘His face is turned toward the past. Where we perceive a chain of events, he sees one single catastrophe which keeps piling wreckage and hurls it in front of his feet. The angel would like to stay, awaken the dead, and make whole what has been smashed. But a storm is blowing in from Paradise; it has got caught in his wings with such a violence that the angel can no longer close them. The storm irresistibly propels him into the future to which his back is turned, while the pile of debris before him grows skyward. This storm is what we call progress.’10

For Magritte and Cotton, images (signifiers) are slippery. They are slippery because they don’t behave in the way their signifieds do, and because they don’t stay attached to their signifieds. You can do things with an image of a pipe or a bird that you can’t do with an actual pipe or an actual bird. Images rhyme and relate in ways their referents don’t, and you can picture things that have no parallel in reality. It’s as if, in Cotton’s paintings, real-life conflicts that may have long ago ended continue to play out in a parallel world of images, perhaps with different results. For instance, in Cotton’s 2010 painting Son(s) of Gods, a musket discharges a disembodied moko pattern in place of gunsmoke—a visual non sequitur. Even if we could draw some conclusion from this image, what would we do with it (now)? How might we apply it to the real world?

The title of Cotton’s show—The Treachery of Images—was more than just a nod to Magritte. It was a manifesto of sorts, one that distanced Cotton from the prescriptive identity rhetoric that was settling around his work a decade or so ago. In the Maori meeting house, we are told, images are not ambiguous, only familiar and reassuring. They situate the locals within the family, within the community, within history, within the land, within the universe. They tell the faithful who they are. However, in arguing that images are traitors, Cotton turns his back on this idea. Saying that images are treacherous implies that they have agency, lives and projects of their own, and that they are duplicitous—not to be trusted. As much as his art is about meetings (collisions more like), it is the antithesis of meeting-house art.11

•

Cotton’s work broaches an old dilemma: (how) can you be Maori and modern? This has long been a vexed matter, not just because what is commonly considered authentically Maori predates exposure to Western modernity, but because Maori culture is inherently traditionalist, being based in ancestor worship and whakapapa (understanding people and things in terms of their origins). Maori and modern may be chalk and cheese. Responses to the Maori-modern dilemma polarise. Some argue that contact was catastrophic for Maori culture, others that the culture is dynamic and that foreign ideas and values have been absorbed and adapted into its framework. Both ways of thinking are wishful.

Cotton’s breakthrough works, like those shown at Hamish McKay Gallery in 1993, were explicitly keyed to the dilemma. They drew on the creole iconography of Rongopai, the novel meeting house built for Te Kooti in 1888, in the wake of the Land Wars, when the people were dispossessed, disillusioned, and disoriented. It remains hard to know if Rongopai’s carefree appropriation of European materials, motifs, and manners was a canny, empowered response to encroaching modernity or a symptom of cultural breakdown—clutching at straws. This ambiguity intrigued and transfixed Cotton. In the early twentieth century, the Ngata Revival would sidestep this chapter of Maori art (sometimes called ‘Maori folk art’), asserting classical art styles in its programme for cultural survival in modern times.12 However, in the 1960s and 1970s, the pendulum swung back, when the Maori modernists promoted the idea that Maori and modern could be ‘blended’: Arnold Wilson conflating Henry Moore with pou and Paratene Matchitt scrambling Victor Vasarely’s op art with tukutuku.13 In the 1990s, it seemed that Cotton might be pursuing precisely this kind of merger. But, since his City Gallery show, it has become ever clearer that he is grappling with the Maori-modern conundrum in a very different way. Neither a conservative revivalist nor a utopian blender, Cotton has created a new idiom, which he has called ‘Maori Gothic’.14

I was once told that Cotton’s favourite film is F.W. Murnau’s Nosferatu (1922), and it’s telling to compare his recent paintings with that film’s source, the classic Gothic vampire novel Dracula. Bram Stoker’s tale—published about ten years after Rongopai was built—also had a conflicted relationship with modernity. Stoker’s Victorian characters were modern, they were neophiles: they rode trains, practiced stenography, used typewriters, sent telegrams, dictated their scientific observations onto wax cylinders, and transfused blood. But, for all their scientific and industrial nous, they were both plagued and excited by a dark occult figure from an earlier, aristocratic, pre-enlightenment time. This vampire was a remnant—the last of his kind. Dracula was not the past as appropriated by the present to explain and legitimise itself, but a past that couldn’t be assimilated, couldn’t be read—a past that exercised its own excessive claims on the present. Stoker was explicit about this. At Castle Dracula, a twitchy Jonathan Harker famously observed: ‘unless my senses deceive me, the old centuries had, and have, powers of their own which mere “modernity” cannot kill.’15

Vampires are a sign that modernity is a house built on sand. As Jeff Wall explains: ‘The vampire is neither alive, nor dead, but exists in an accursed state of irremediable tension and anxiety … he embodies a certain sense of cosmic grief … the vampire signifies not simply the unwillingness of the old regime to die, but the fear that the new order has unwittingly inherited something corrupted and evil from the old, and is in the process of unconsciously engineering itself around an evil centre. The presence of the phantasm of the vampire in the consciousness of modern, liberal men signifies the presence of an unresolved crisis in the creation of the modern era itself.’16

In coining the term ‘Maori Gothic’, Cotton acknowledges the haunted, vampiric quality of his paintings. With their glaring severed heads, suicide cliffs, tormented skies, graffiti ‘written on the wind’, and plummeting birds, they seem spooky and ominous. It’s as though, in the course of his iconographic enquiries, the artist, like some latter-day Lord Carnarvon, had unwittingly prized open a Pandora’s box, releasing ancient, dark, disavowed forces into the world. Under their corrupting influence, familiar items now behave in unfamiliar ways. Passages from the good book, lava lamps, and baseball bats begin to mean something else entirely. Everything is haunted; nothing can be trusted.

But how exactly is Cotton positioning himself in relation to Maori-as-vampiric? Does he see the Maori vampire as pathetic or powerful, as provoking sympathy or dread? To what extent is he on the vampire’s side and to what extent is he invested in the new world that the vampire threatens? Many interpreters presume Cotton sides with his historical Maori imagery, but the reality may be more complex. After all, Cotton came to that imagery late, largely as a result of the research he conducted in order to teach Maori art in the early 1990s.17 His historical Maori imagery may be less familiar, less ‘natural’, and more mysterious to him than his modern images of digital clocks and PlayStations. Perhaps his position is not simply that of a Maori insider, but simultaneously that of insider and outsider. When interpreters align Cotton with his Maori imagery, as if he were simply a booster in matters Maori, they neglect and override his work’s experimental, surrealist imperative. Cotton thrusts images together to explore the outcome, not to illustrate a point or argue a case.

They say that the meeting house locates and grounds its community, providing some turangawaewae, some place to stand. If so, Cotton’s work does the opposite. It’s all about uprootedness, uncertainty, nowhere to stand, being up in the air. For Cotton, being Maori is not conservative; it’s not about a sense of cultural certainty, the succour of tradition. It’s more about identifying with and embracing the epistemological crisis that came with contact, a crisis that split open signs, tearing signifier from signified, turning images into traitors. It’s about being fundamentally conflicted. And perhaps Cotton finds a certain pleasure and freedom in this, where all meanings and frameworks, Maori and modern, might come unstuck, or, equally, repossess and plague each other. Rather than reconcile the indigenous and the modern, Cotton revels in their terrific, caustic, game-changing antagonism, reaping its dark abundance as that ‘pile of debris before him grows skyward’.

For Cotton, it seems, biculturalism is not about finding a bureaucratic solution, not about policy and partnership, not about reconciliation, but rather, as Ian Wedde once put it, about keeping a certain problem alive,18 and, if not alive, at least undead.19

.

[IMAGE: Shane Cotton Back Words 2011]

- Jonathan Mane-Wheoki, ‘Toi Hiko: Maori Art in the Electronic Age’, in Hiko: New Energies in Maori Art (Christchurch: Robert McDougall Art Gallery, 1999), np.

- Christian Palmer and Mervyn L. Tano, Mokomokai: Commercialization and Desacralization (Denver: International Institute for Indigenous Resource Management, 2004. nzetc.victoria.ac.nz/tm/scholarly/tei-PalMoko-t1-body-d1-d3-d1.html.

- Colin McCahon, Colin McCahon: A Survey Exhibition (Auckland: Auckland City Art Gallery, 1972), 26.

- Comte de Lautréamont (Isidore Ducasse), Les Chants de Maldoror (1868–9).

- The French title, La Trahison des Images, is sometimes also translated as The Treason of Images.

- This carving is thought to have been made in the 1840s by Patoromu Tamatea of Ngati Pikiao for a new Catholic chapel in the Bay of Plenty. The carver indicated the Virgin’s spiritual status in Maori terms by giving her a full moko. The piece was rejected by the local priest.

- Back Words is permeated with references to the Virgin. The hymn ‘Beneath Thy Protection’ addresses her. And, according to Cotton, the image on the billboard is based on Jean Fouquet’s Virgin and Child (ca. 1450).

- Incidentally, Magritte’s The Future of Statues (1937)—with sky and clouds painted on a commercial plaster reproduction of Napoleon’s death mask—offers another precedent for Cotton’s camo-heads. Magritte’s work suggests transcending death through dreaming.

- Cotton’s painted bats also recall Marcel Duchamp’s notes on the idea of the ‘reciprocal readymade: use a Rembrandt as an ironing board’ in The Green Box (1934).

- Walter Benjamin, ‘Theses on the Philosophy of History’ (1940).

- Although, I note, Cotton did paint kowhaiwhai panels for the wharekai at Motatau Marae, which opened in 2009.

- For more on Ngata, see Jeffrey Sissons, ‘The Post-Assimilationist Thought of Sir Apirana Ngata’, New Zealand Journal of History 34, no. 1, 2000: 47–59.

- Thinking here of Matchitt’s 1965 mural Niho Taniwha.

- Cotton titled his 2005 Hamish McKay Gallery show Maori Gothic.

- Bram Stoker, Dracula (1897), (London: Penguin, 2003), 43.

- Jeff Wall, ‘Dan Graham’s Kammerspiel’ (1985), in The Gothic, ed. Gilda Williams (London: Whitechapel Gallery, 2007), 211–2.

- From 1993 to 1996, Cotton taught Maori art at Te Putahi-a-Toi, School of Maori Studies, Massey University, Palmerston North. As Cotton explains: ‘I shifted to Palmerston North and took up a lectureship in the Maori Studies department, and all of a sudden I was exposed to a different kind of history, a Maori colonial history—it was something that I didn’t know about in any great depth but I had to try to teach the stuff. I was learning, teaching, learning, teaching, all at speed, and it started feeding into my painting. So a lot of the work through the nineties was dense; it was dense with biblical scripture and dense with Maori history, which was new to me. I wasn’t so much trying to teach people about this stuff as trying to understand it for myself.’ ‘Shane Cotton: Stamina, Surprise, and Suspense’ (interview with Justin Paton), B.170 Bulletin of Christchurch Art Gallery, Summer 2012–3: 14.

- See Ian Wedde, ‘The Delft Effect’, in ‘Voices He Putahitanga’, Midwest, no. 3, 1993: 16.

- ‘For all its supposed darkness and disruption, the Gothic is fundamentally romantic and reassuring: it’s a mode of enjoyment, a way of taking pleasure. And that’s why it will never be part of a utopian bicultural solution. Because in preferring the Gothic, we prefer the problem.’ Robert Leonard, ‘Hello Darkness: New Zealand Gothic’, Art and Australia 46, no. 1, Spring 2008: 95.