Shane Cotton (Auckland: Auckland Art Gallery, 2004).

It’s just over a decade since Shane Cotton unveiled his paintings drawing on so-called ‘Maori folk art’, that hybrid figurative painting idiom that emerged in the late-nineteenth century. A recent Ilam graduate, Cotton had already made a name for himself with his bravura biomorphic abstracts, their titles prompting viewers to read their organic goings-on in Maori cultural terms. But his style shift was so dramatic, it almost seemed to be an about-face. Cotton’s engagement in matters Maori suddenly felt explicit, urgent, and deep. I saw those two groundbreaking shows, at Wellington’s Hamish McKay Gallery in 1993 and Auckland’s Claybrook Gallery in 1994. At the time, the work seemed to come out of thin air. Now, in retrospect, it seems to totally exemplify that moment, with the country unpacking biculturalism’s historical baggage in the wake of the Treaty sesquicentennial.

Cotton came across Maori folk art while doing research for his new job, lecturing in the Maori Studies department in Palmerston North’s Massey University. Maori folk art was a product of a major cultural upheaval, a time of cultural trauma for Maori. After the Land Wars, Maori society was fragmented, in strife, reduced and ravaged through conflict and disease. However, on the East Coast, meeting houses associated with Te Kooti, the rebel chief and founder of the Ringatu faith, were being decorated with idyllic, folksy paintings reflecting Pakeha influence. In these houses, paintings took the pride of place formerly reserved for carvings. The iconography included potted plants and flowers, flags, ships and trains, kings and queens, and representational variants of traditionally abstract kowhaiwhai patterns. While the new art found East Coast Maori assimilating means, motifs, and manners from the very culture bearing down on them, the work was also freighted with resistance. The appropriations were recoded through Maori frames of reference and concern. Today, when we look at Maori folk art, it seems amazing and inventive, but also problematic. It’s hard to know to what extent it exemplifies a confident adaptive culture grappling with change or one over impressed.

Cotton’s paintings were figurative but hardly naturalistic, more symbolic—like heraldry. Cotton often used one image—shelving, a tree, scaffolding—to provide an organising system for others, creating systems of nested metaphor. Scale was not naturalistic but symbolic—still-life objects could be the size of mountains. Some of Cotton’s schemes were derived from nineteenth-century houses (like the potted plants, symbolising guardianship of land), others he invented (a pincushion representing the land, pierced by the standards of occupation like Victorian hatpins). The paintings were battlegrounds for competing signs—contra-diction. Cotton served up Mount Taranaki in a pot, symbolising Maori guardianship, yet the venerated mountain was already mediated through Charles Heaphy’s colonial gaze and peppered with platforms bearing giant numbers evoking colonial surveying, division, and appropriation of land. Cotton’s Maori/Pakeha juxtapositions did not just suggest conflict, they also suggested affinity. His sepia-toned instant-history palette, for instance, recalled both European old masters and the ochres used in traditional Maori art. Paradoxically, it was the complete antithesis of Maori folk art’s technicolour exuberance.

Cotton’s paintings referred to struggles over land, but they were as much about struggles over signs—naming rights. Superimposing hostile frames of reference, it was often unclear whose side the component images were on, through whose interests they should be read. Take the painting Te Ao Hou (1993). It’s like something out of Gulliver’s Travels. The title translates as ‘the new world’, meaning the post-contact world, the world of the Pakeha. It shows a giant colonial cowboy boot covered in Maori scaffolding. The boot suggests incoming values, but it is also evacuated. Was the scaffolding created to build the boot, or as siege machinery from which to scale it, attack it? Is the boot a memorial or a Trojan Horse? Te Ao Hou was, famously, the title of a magazine published by the Maori Affairs Department in the 1950s and 1960s, during Maori detribalisation, the ‘second migration’, the drift to the cities. It had a schizophrenic agenda: to maintain cultural values but also ease integration. Cotton’s painting certainly suggests an ambivalence about the gifts of the Pakeha.

.

In New Zealand in the early 1990s, Cotton’s work was timely. It meshed with where contemporary art was at. For over a decade, postmodernism had promoted intertextuality: the idea that we read texts through other texts, that signifiers are only provisionally linked to their signifieds, that marginalised voices might speak through cracks or displacements in the dominant discourse. Quotation—appropriation art—was still all the rage. Indeed, Cotton’s paintings beautifully illustrated Barbara Kruger’s words: ‘We loiter outside of trade and speech and are obliged to steal language. We are very good mimics. We replicate certain words and pictures and watch them stray from or coincide with your notions of fact and fiction.’1 But more surprising was that Cotton’s work suggested that the latest postmodernist insights may have been anticipated in the work of those neglected East Coast artists in their prior moment of cultural upheaval. Suddenly nineteenth-century Maori folk art seemed hugely relevant to now.

Like his forebears, Cotton worked in references from his own time—basketballs, digital clocks. Many of these images were hijacked from overseas contemporary appropriation artists like Jeff Koons, Haim Steinbach, and Imants Tillers (Cotton also quoted local borrowers like Colin McCahon, Gordon Walters, and Dick Frizzell). Perhaps Cotton was giving them a dose of their own medicine, perhaps he saw an affinity between hip postmodernist image-scavengers, Maori folk art, and his own strategies, perhaps both. But with concern raging around Pakeha artists like Walters and Frizzell purloining Maori imagery, his work was provocative. The ‘appropriation debate’ had become polarised: one side blindly asserted the artist’s right to use whatever, the other insisted on Maori copyright over material originating within their tradition. Cotton’s works deranged and deepened the terms of the discussion by considering how Maori identity and authorship might be invested in images not strictly of Maori origin, even as they spot lit the historical alienation of Maori land.

Like Maori folk art, postmodernism was big on allegory. Allegory occurs when one text is doubled by another; the Old Testament, for example, becomes allegorical when it is read as a prefiguration of the New. In his seminal essay ‘The Allegorical Impulse: Toward a Theory of Postmodernism’, Craig Owens writes: ‘Allegory first emerged in response to a … sense of estrangement from tradition; throughout its history it has functioned in the gap between a present and a past which, without allegorical reinterpretation, might have remained foreclosed. A conviction of the remoteness of the past, and a desire to redeem it for the present—these are its two most fundamental impulses …’2 Owens goes on: ‘Allegorical imagery is appropriated imagery; the allegorist does not invent images but confiscates them. He lays claim to the culturally significant, poses as its interpreter. And in his hands the image becomes something other … He does not restore an original meaning that may have been lost or obscured; allegory is not hermeneutics. Rather, he adds another meaning to the image … [Allegories] simultaneously proffer and defer a promise of meaning; they both solicit and frustrate our desire that the image be directly transparent to its signification. As a result, they appear strangely incomplete—fragments or runes that must be deciphered.’3

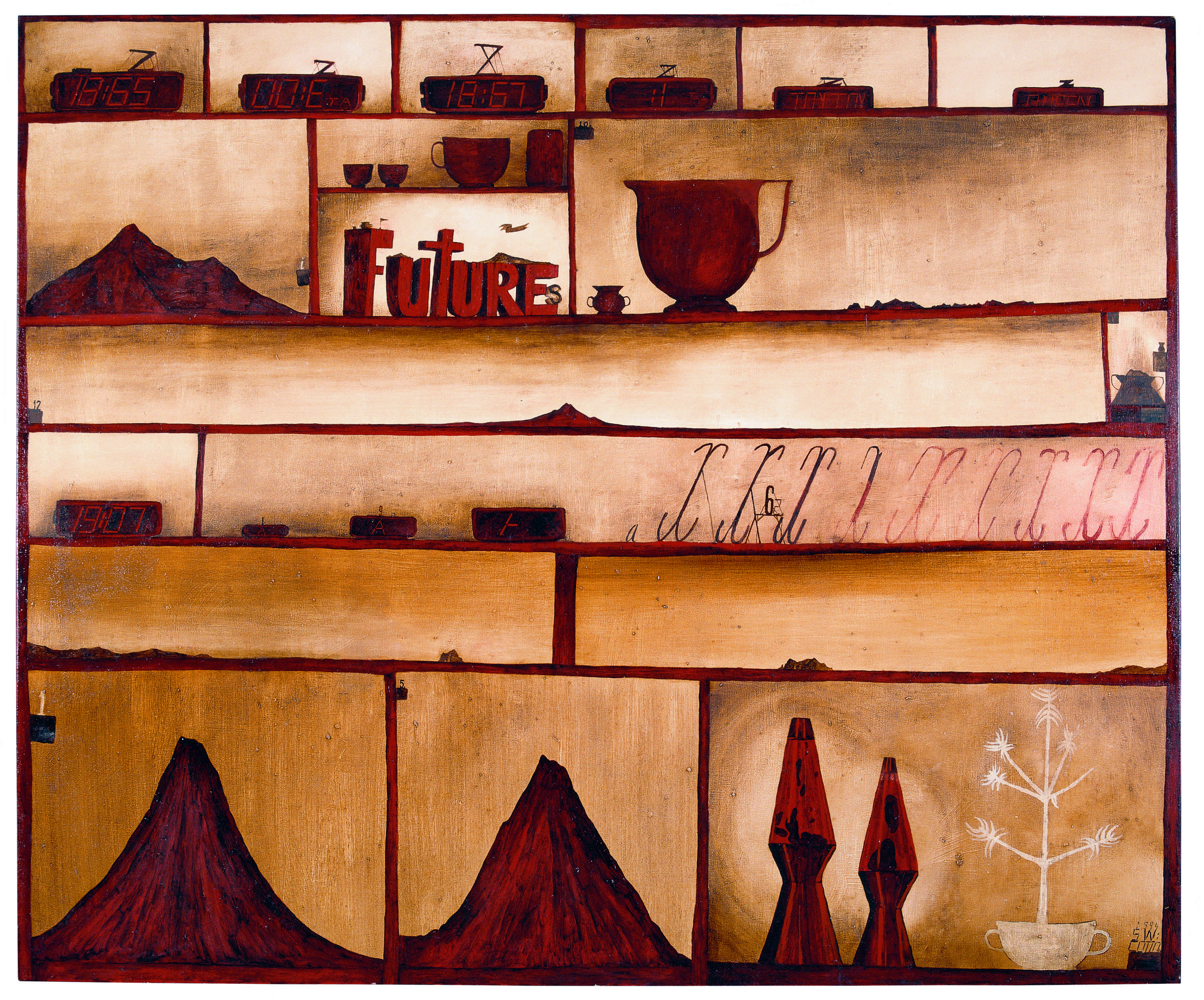

Prophets typically speak in allegories, projecting the future as the fulfilment or redemption of the past. They fold time and space, then onto now, there onto here. In the nineteenth century, new Maori spiritual leaders often read their lot through the Bible. Cotton’s painting Daze (1994) is all about prophecy and foregrounds the use of allegory. The painting is subdivided like a Haim Steinbach shelving unit, but it also recalls the stacked landscape spaces of McCahon’s Six Days in Nelson and Canterbury (1950).4 Into the painting’s cubby-holes Cotton has shelved image-objects: moderne lava lamps sit alongside primordial volcanoes, copperplate Xs from Ngapuhi chief Hongi Hika’s practice handwriting, pots and cauldrons, the word ‘FUtUREs’ written in McCahon block-cubist letters (its T, a Christian cross), and digital clocks (another nod to Steinbach). The clocks tell different times: 18:65, 18:67, and 19:07 (in 1907 the Tohunga Suppression Act made it a crime for Maori to predict their future). Daze proceeds by analogy, its quotes radically recontextualising one another.

Allegories are open to interpretation, typically sustaining contradictory levels of meaning. Daze doesn’t necessarily simply affirm Maori values. The title is loaded. It’s a pun on ‘days’—as in McCahon’s Six Days—proposing the work as a chronicle. It also suggests being stunned by a clarifying vision, or, less optimistically, being ‘dazed and confused’, caught short in history’s headlights. Daze opens up a problem: to what extent were Maori folk artists insightful or blind? Did their allegories offer them leverage on their situation, or was history passing them by? In skirting this question, Daze hones in on one of Cotton’s key themes: Maori coming to terms with modernity, in the late nineteenth century, in the form of surveyor’s pegs and flagpoles, and now, in the form of basketballs and digital clocks.

.

Cotton’s early figurative paintings were inspired by East Coast houses, but he soon began to reflect on his own tribal background. He’s Ngapuhi, from Northland. Today, Ngapuhi meeting houses have almost no decoration, their art having been suppressed by colonial missionaries who considered it hedonistic and pagan and certain images even satanic. (The missionaries were particularly concerned by Ngapuhi eel imagery, confusing the tribal eel-guardians with their own evil snake from the Biblical tree of knowledge.) In 1996, Cotton started a new body of work replaying the clash between Maoritanga and Christianity as a war between sign systems. Some say Christianity usurped Maori traditions. Another, more optimistic view is that ‘perhaps Maori did not convert to Christianity so much as convert Christianity, like so much else that Pakeha had brought, to their own purposes’.5 The clash between Maori values and Christianity was played out in different ways in different places and moments in a drama of ‘collision and collusion’. Cotton expresses this through curious hybrid images, like the crucified tiki head in Lying in the Black Land (1997–8) (doubtless a riposte to the feather-cloaked mokoed Maori Jesus etched into the window of St. Faith’s Church, Ohinemutu).

Cotton doesn’t make things easy. He doesn’t present Christianity here and Maori there, but hybridises them. So even as things stand in opposition, they are already infected by what they oppose. He Pukapuka Tuatahi (1999–2000)—the title means ‘the first book’—presents two elements in counterpoint. The bottom half is dominated by a sea of Maori writing. It’s Genesis, first book of the Bible, recast in Te Reo. The text comes from the Paipera Tapu, the nineteenth-century Maori bible. A gang patch dominates the space above, like a rising or setting sun or moon. Its outer band features a phrase from the Northern prophet Papahurihia, written in a Gothic olde-English face. It translates as ‘serpents of the hot gods’—a great name for a gang. The legend frames a complex stylised serpentine form, combining suggestions of manaia, Ngapuhi eel, and Biblical snake. In morphing these forms, Cotton suggests the conflation of their deeper meanings, exploiting formal affinities as if they were indicative of deeper cultural affinities. In doing this, Cotton suggests the way nineteenth-century Pakeha and Maori alike recognised and misrecognised what they saw through what they knew. In forging his images. Cotton isn’t just illustrating how this happened in the past, he’s making it happen now. Our readings of his obscure images depend on our predilections. Cotton’s work isn’t pitched to an ideal reader grounded in this stuff, but to a diversity of partial readers trying to find their way in through what they know. It’s premised on the possibility of misrecognition, generative misreading.

.

Cotton’s use of fragmented imagery plays off two local precedents: the modernist Colin McCahon and the postmodernist Richard Killeen. He references both. In using a bit of image from here, a bit of text from there, McCahon forged singular images with real mythic force; images which resonated and convinced despite their fragmentary quality. It made him our most important modern artist. Following in McCahon’s wake, Killeen preferred to undermine the authority behind signs. He was a textbook ‘death of the author’ postmodernist. Since the early 1980s, he has been synonymous with his cutouts: paintings that are collections of image-fragments that lack an overarching rationale, a common thread, and are available for physical and conceptual reordering. The cutouts countered both traditional narrative pictures and McCahon’s crypto-mythic work, rejecting both as authoritarian. McCahon and Killeen were chalk and cheese: McCahon was heavy, Killeen light; McCahon religious, Killeen secular. McCahon wanted to harness the force of signs, Killeen to deconstruct them.

Cotton works the McCahon–Killeen continuum. Sometimes, his works feel more like McCahons, say in He Pukapuka Tuatahi, where images cohere into potent affective symbols. Sometimes, they feel more like Killeen cutouts, like in The Waka Transformation (2001), where dispersed images float in provisional arrangements that beg the viewer to connect-the-dots, to accord them meaning. Typically there’s a bit of both going on. Cotton pushes and pulls the viewer back and forth along the McCahon–Killeen continuum—the authority/anti-authority continuum—recontextualising it within Maori cultural struggles. Here things become complex, because Maori don’t speak from a culturally dominant position—their relation to authority is different. When Killeen has a go at McCahon, he’s supposedly fighting the power, attacking McCahon as an authority figure within the dominant culture.6 But, what’s the equivalent in Maori terms? Do we equate Pakeha attacks on dominant Pakeha values with Maori attacks on the authority of Maori tradition, or with assertions of Maori authority as implicitly critical of dominant Pakeha values? It’s unanswerable, because the situation is not symmetrical. It gets more messy: things turn into their opposites. Killeen assumes that resolved, integrated images—either the traditional narrative kind or the mythic McCahon kind—embody authority. But integrated images can be a response to, a compensation for, cultural breakdown. In times of trouble, people rally round affirming images—church, whare, flag. That’s conservatism. Similarly, disintegrated fragmented images might conveniently dissemble authority. Conjuring with structure and lack of structure, legibility and illegibility, clarity and confusion, Cotton’s works snare us in this problematic.

.

For his 2003 City Gallery Wellington survey show, Cotton created a surprising new body of work. Seven diptychs were hung in line, to be read as a group. Painted in a hard-edged pop style, they jettisoned the classic mist-of-time sepia-toned look. As William McAloon quipped, ‘he’s gone from paintbrush to airbrush’.7 The series features new images—bull’s-eye targets, birds, and mokomokai—which turn up in different combinations and scales, echoing from painting to painting. The old pictorial architecture is almost entirely gone; images float in inky voids mostly, in airbrushed cloudy atmospheres occasionally. The relationship between the images seems entirely provisional, arbitrary. They feel like movable tokens in a board game. The works pose as puzzles: what sense to make of the parts, individually, collectively? Take Broken Water (2003). Images include a mokomokai in profile, decorated in a blue camouflage pattern; a scratchy, barely visible Jesus, with arms outstretched; the word ‘Takauere’ in a Gothic stencil face, referring to a Ngapuhi taniwha; a tui or parson bird, a native bird that could also represent a missionary; a bull’s-eye. A bar of light, suggesting a fluoro tube or Star Wars light-sabre, bridges the two panels. These images have meanings and connections we can research and elaborate further, but in doing so we may only get mired deeper in the puzzle. Resolution withheld.

The new works have martial and morbid undercurrents. Birds are fatalistically superimposed on bull’s-eye targets that recall British airforce insignia as well as Jasper Johns and Kenneth Noland target paintings. Kikorangi (2003) resembles the flank of a fighter plane, where the kill-score is enumerated in enemy insignia. In addition to native birds, targets, and mokomokai, its heraldic array also includes a figure of Jesus and an American eagle. The work suggests purloined trophy-signs redeployed within a hostile signifying system.

This idea perhaps underlies Cotton’s interest in mokomokai. In the colonial period, the heads were traded with Europeans as curios. (This led to the practice of Maori tattooing slaves; eventually harvesting heads to meet demand.) Today, mokomokai are being withdrawn from museum displays and aggressively repatriated to meet current Maori sensitivities. Playing with such contentious hot-potato material, Cotton is moving into an ethically unmapped zone. Rather than tattooed his mokomokai are filled in with camouflage patterns (not green-and-brown military camo, but funky fashion camo) and rainbow stripes. This Yellow Submarine super-graphics treatment has been interpreted as Cotton transcending the issues surrounding mokomokai. It could equally imply lack of concern.

Cotton’s works cue but frustrate reading. Much of the writing around Cotton presents itself as exegesis and gloss, bypassing the work’s overt obscurity. As Leigh Davis put it: ‘Most people hate the unreadable … like bees or ants, we express this hatred by building cities and comprehension through and around the unreadable to scaffold it, thereby seeking to stabilise and colonise. In this way the unreadable becomes riddled with interpretation.’8 Rather than ascribe specific narratives to Cotton’s paintings, it has been suggested that we give ourselves over to the sense of cultural uncanny they generate. This idea frames the work as a kind of surrealism, with Cotton’s contrived meetings between Maori and European images operating like the infamous ‘chance encounter of an umbrella and a sewing machine on an operating table’. If surrealism typically engages a personal psycho-sexual unconscious, Cotton’s surrealism is keyed to a collective historical-cultural unconscious. But it is equally a matter of unfinished business, things swept under the carpet.

There is some precedent for Cotton’s work in surrealism, particularly in the work of dissident surrealist Georges Bataille. In his essay ‘On Ethnographic Surrealism’, James Clifford addresses Bataille’s corrosive use of ethnography in his magazine Documents (1929–30). Bataille’s magazine took as its problem—and opportunity—the fragmentation and juxtaposition of cultural values. Clifford writes: ‘Documents, particularly in its use of photographs, creates the order of an unfinished collage rather than that of a unified organism. Its images, in their equalising gloss and distancing effect, present in the same plane a Chatelet show advertisement, a Hollywood movie clip, a Picasso, a Giacometti, a documentary photo from colonial New Caledonia, a newspaper clip, an Eskimo mask, an Old Master, a musical instrument—the world’s iconography and cultural forms are presented as evidence or data. Evidence of what? Evidence, one can only say, of surprising, declassified cultural orders and of an expanded range of human artistic invention. This odd museum merely documents, juxtaposes, relativises—a perverse collection.’9 Abolishing the easy distinction between Western forms and exotic ones, Documents ridicules and reshuffles cultural orders, exposing cultural norms as radically contingent, facilitating a breakdown in cultural authority. It denies the reader the presumption of occupying an ideal enlightened vantage point from which everything might become clear.

To see what surrealism means for Cotton’s biculturalism, it’s worth considering the difference between surrealism and psychoanalysis. Crudely speaking, psychoanalysts decode latent messages coded in dreams as evidence of trauma, with a view to healing patients, returning them to normal society. Surrealists, however, are less interested in decoding dreams, making sense of them, than reveling in their manifest non-sense, enjoying the leverage their poetic craziness offers over the prevailing common sense. Surrealists find liberty in their symptom. As surrealism, Cotton’s work can be distinguished from traditional Maori art. For its intended readers, the traditional whare is a holistic integrated structure, linking cosmology and whakapapa; community and place; past, present, and future. It provides turangawaewae, a place to stand. It embodies and locates collective values to focus identity and provide a bulwark against threatening values: us and them. But rather than reassuring and integrating, Cotton’s new works are confusing and disorienting. They have been fired out from the studio like cultural depth charges or Rorschach blots (our readings of them betraying more about us). Cotton has come a long way since those first figurative paintings a decade ago. Despite their ambiguity, they were more integrated, more emblematic works. They had pathos: they advertised a need for consideration and care. They prompted the viewer to take stock of unjust history, to think again. Ten years on, it’s like Cotton has finally drawn out the radical implications of those early paintings. His new works are feral. They are not cultural propaganda, not right-on sermons, but an exhilarating experiment in cultural thinking played out though the rhetorics of painting, its conceits and contingencies; an experiment in which the outcome is not predetermined, and in which we, the audience, in all our contingency, don’t just observe but play a part. Not only do we face the music, we’re its sounding board.

.

[IMAGE: Shane Cotton Daze 1994]

- Documenta 7, vol. 1 (1982), 286.

- October, no. 12, Spring 1980: 68.

- Ibid., 69–70. Owens’s idea is echoed by Lara Strongman when she writes: ‘The process of reading’ Cotton’s paintings is one of piecing together fragments. The viewer’s role is akin to that of an archaeologist attempting to piece together the lost history of a civilisation from a few shards of broken pottery, some coins and an image in smoke on the wall of a cave: the possibilities for interpretation are endless, and depend very much on the perspective one brings to the puzzle.’ ‘Ruarangi: The Meeting Place Between Sea and Sky’, Shane Cotton (Wellington: City Gallery Wellington and Victoria University Press, 2004), 17. I have drawn extensively on Strongman’s essay throughout my text.

- McCahon’s painting was itself an allegory, reading the artist’s six-day bike trip through the Creation. McCahon employed the prophetic voice throughout his work.

- Michael King, The Penguin History of New Zealand (Auckland: Penguin Books, 2003), 144.

- The question—whether McCahon really is aligned with the authority of the dominant culture—is best left to another day.

- In conversation with the author, April 2004.

- ‘Maori Bay Quarry: Maori Prophets in the Work of Colin McCahon’, Art Asia Pacific, no. 22, 1999: 84.

- ‘On Ethnographic Surrealism’, The Predicament of Culture: Twentieth-Century Ethnography, Literature, and Art (Cambridge: Harvard University Press, 1988), 133–4.