Art and Text, no. 63, 1998. Review, Shane Cotton, Hamish McKay Gallery, Wellington, 1998.

Faced with lengthy speeches to deliver, classical orators developed an ‘art of memory’. They first imagined a building with rooms and portals, then furnished it with images standing in for their main points. These mental notes had to be bizarre in order to be memorable—condensed like dream images. Orators would imagine themselves wandering through the building, encountering and decoding the images along the way, and would then deliver their thoughts in this precise sequence. Intriguingly, New Zealand’s Maori meeting houses parallel this classical art. They are real buildings, mnemonic structures embellished with images of ancestors—family trees. Though they anchor oral histories they are not discursive. They don’t tell you what you don’t know; they simply remind you of what you already do know. To outsiders they might seem bizarre, inexplicable, surreal; but to locals, they are the apotheosis of common sense.

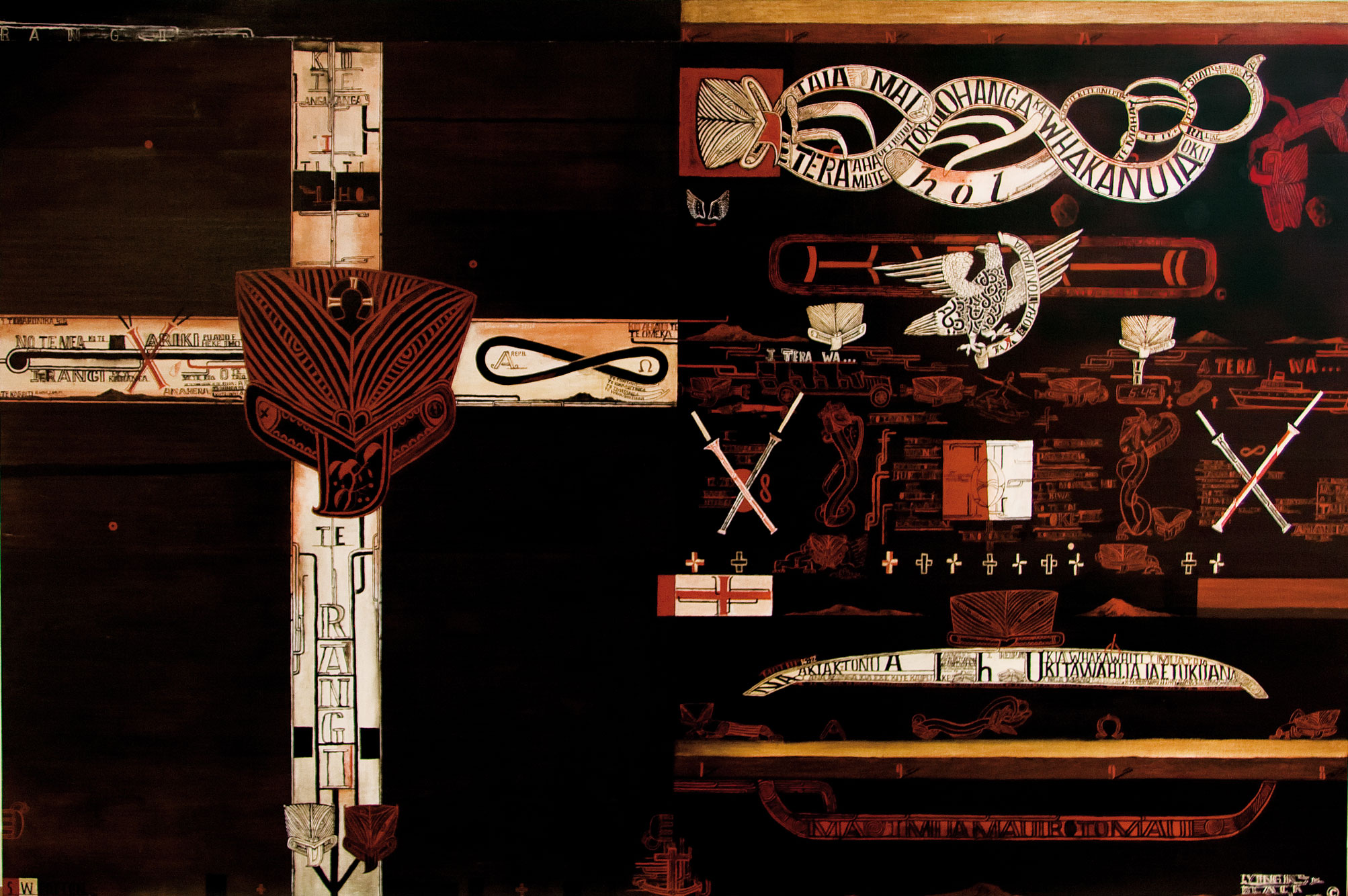

Shane Cotton’s paintings play off this ancient art of memory. A young Maori artist, his works are thick with heraldic and fragmentary images, mostly derived from post-contact Maori art when European images, materials, and ideas were being absorbed and recoded, and it still wasn’t clear if Maori were taking advantage of new things or being done in by them. Just as ancient orators located their images within a given architecture, Cotton’s contents are stashed into preexisting formats: shelves, scaffolding, stacks, trees. The paintings seem both ordered and not, like a museum storeroom packed with jumble. Though things are in their places, perhaps no one can remember what they were doing there. Indeed Cotton’s antiqued, bituminous paintings might themselves be mistaken for museum pieces.

These works function as a kind of academic exploration into history (Cotton lectures in Maori art at Massey University) and as weird (a kind of cultural surrealism). This surrealist bent is crucial to the current show which paints a portrait of Cotton’s tribal area ‘up north’—Ohaeawai—where indigenous art traditions were all but quashed by Christianity. As if in reply, Cotton creates a space where Maori imagery once again meets Christian iconography, like the poetic encounter of an umbrella and a sewing machine on a dissecting table. It’s no mistake to see Cotton’s vast panoramic landscapes as echoing those of Salvador Dali. Lying in the Black Land (1998) even incorporates a soft watch, as if shorthand for Maori concepts of time. The new works also feature quotations from the Maori Bible, kowhaiwhai patterns, a tiki head on a cross, primordial landscapes, darkness and light, and digital clocks. Shane Cotton’s hybrid of old-master technique and what used to be called ‘Maori folk art’ offers a world that is brooding and ominous, cryptic and portentous, archaeological and eschatological, simultaneously about the past and the future.

Surrealism revels in the condensation of the dreamwork, but eschews unraveling and healing, which is the work of analysis. In fact, surrealism privileges the poetry of the troubled mind—and the possibilities for remaking the world implicit in its strange grammar—over transparency, common sense, and cure. Similarly, Cotton creates a difficult, dense space in which contradictions remain charged and complexity proliferates. A reconciliation of Christian and Maori iconography is promised but coyly withheld. For Cotton, biculturalism has never been about finding a solution but about revitalising the problem.