Art Monthly Australasia, no. 327, Autumn 2021.

.

Many of us who work in art museums experience a constant pressure to justify our existence to the purse-string holders operating above and beyond us—as well we should. But, partly because it is hard to quantify art’s intrinsic pleasures and benefits, our habitual justifications tend to address the economic and political knock-on effects of art that appeal to our masters. Over the years, various arguments have come in and out of favour. For example: Art is an industry, employing thousands, generating millions. Art is essential to any creative city that seeks to nurture a creative class. Artists and museums assist urban renewal—gentrification. Art stimulates cultural tourism, with blockbuster shows filling hotel rooms off-season. Art brands us as an open civil society and tells our stories. Art builds social inclusiveness. Arts grads are preferred by employers, because they are more rounded and flexible workers (or is it because their mobility and low expectations are tuned to economic precarity?). Etcetera.1 Such rationalisations are expedient. They contain grains of truth and value, but don’t encompass the reasons artists make art. They instrumentalise art for other purposes. They are a distraction.

And now, there is a new rationale for art and its institutions: they exist to enable our wellness. This idea, added to the others, arrives as part and parcel of a wider physical-and-mental-wellness Zeitgeist. At face value, it might seem convenient for the art world, even tautological: art is good because it is good for us. However, there are devils in the detail. And who exactly is this us? Here, we are no longer speaking of wellness simply as the dictionary defines it, but of a larger framework of assumptions, values and practices—a wellness culture. This culture is increasingly informing the art-museum business. In addition to those wellness-branded supplementary public programs (yoga in the gallery, low-sensory hours, guided meditations, and so on), artworks themselves are being selected and commissioned, organised and framed, to advance and endorse the wellness imperative. Wellness is becoming our purpose.

Art-wellness discourse focuses on art museums—the end of the line, where large publics engage with art. In Art as Therapy, pop philosopher Alain de Botton and art historian John Armstrong assert that art’s and the art museum’s purpose is to provide solutions to life problems, to help us live well and die well.2 They list art’s seven functions as: remembering, hope, sorrow, rebalancing, self-understanding, growth and appreciation. Their approach chimes with the idea, that, in modern secular society, art has taken the place of religion and art museums the place of the church, offering community and guidance, morality and consolation. (They are strangely wedded to a view of museums as good, at a time when many are critical of museums as products of power, privilege, prejudice and plunder.)

Although they love museums, De Botton and Armstrong feel that art-museum professionals have lost sight of their civic duty. They lament the way shows are organised around art-historical principles, periods and movements (a straw-man generalisation). To fulfil art’s therapeutic potential, museum reform is required. The art should instead be orchestrated around our emotional needs, to better feed our souls. They propose rehanging London’s Tate Modern—which, in fact, was never hung chronologically—by devoting floors to emotional themes: suffering in the basement, through compassion, fear and love, to a penthouse of self-knowledge. It is the art museum as a self-help department store—De Botton’s School of Life, with artworks coopted as teaching aids.

The book has been a bestseller, but its views of therapy, art museums and art are limited. The authors have a soft idea of ‘therapy’, as being affirming and forgiving, akin to long walks in nature and Sunday sofa reflection, not finger-wagging, scary, confront-your-bullshit, change-your-life stuff—no shock therapy here. But, more problematic for art, and typical of art-wellness rhetoric, they downplay the position of artists, understanding them simply as servile content and wellness-service providers. Don’t we expect art museums to provide a degree of psychic insulation and legitimacy for artists, to enable them to pursue their audacious inquiries, rather than simply requiring them to perform therapeutic services to audiences?

Nor is wellness the simple, self-evident good it might appear to be. In The Wellness Syndrome, Carl Cederström and André Spicer argue that the current pressure to maximise wellness is actually unhealthy.3 For them, the wellness industry is conservative and insidious, focusing us inwards (on perfecting our minds and bodies), rather than outwards (on changing the world). Wellness, they maintain, has become an insatiable superego command. Its adepts are indulging in a troubling and faddish new puritanism, grounded in neurosis, enabled by narcissism and exploited by a global wellness industry premised on anxiety and addiction—and worth trillions. For Cederström and Spicer, wellness is also covert class war, tied to neoliberal capitalism. On the one hand, it is a discourse of privilege, associated with leisure and luxury (self-optimisation courses, diet smoothies, yoga apps and Goop); on the other hand, it makes us healthier workers, lowering the business and social cost of unwellness, while shaming the unwell into bucking up their ideas and taking responsibility. You’re unwell—your problem!

In New Zealand, we have taken up wellness thinking but given it a more socialist spin, while still capitalising on its faddish currency. Our Government’s 2019 ‘wellbeing budget’ focused on combating structural social inequality, releasing billions of dollars to address mental health, child poverty and family violence. Wellness is now key to government arts policy and a cornerstone of Creative New Zealand’s thinking. More agencies are emerging to spread the word. In 2019, Carmel Sepuloni – then Minister of Social Development and Associate Minister for Arts, Culture and Heritage—launched Te Ora Auaha: Creative Wellbeing Alliance Aotearoa, to tackle mental health, social inclusion, age concern and social and cultural inequality through art. In discussing the Alliance, Peter O’Connor, Professor of Education and Social Work at the University of Auckland, described the arts as ‘an innovative and cost-effective way to enhance wellbeing’.4

The wellness agenda is also embodied by our national museum, Te Papa in Wellington. In March 2018, it unveiled the NZ$8.4 million redevelopment and expansion of its art galleries into Toi Art. Prime Minister Jacinda Ardern, then also Minister for Arts, Culture and Heritage, opened the show. In the press release, she was quoted: ‘Toi Art is all about the fact that art is for everyone, and I believe every New Zealander will find something here that speaks to them, something to amaze and challenge them. Art is a vital part of our lives. It is fantastic that as a free, family-friendly experience, the new gallery will make it more accessible to more people.’5

In addition to the usual collection-based displays, the new Toi Art show featured two commissioned wellness-themed installations by Tiffany Singh, promoting empathy and mindfulness. For Indra’s Bow, Singh suspended fair-trade glass bells in an arc from coloured ribbons. It is a work to smell as much as see. The bells contain aromatic herbs and spices, as well as gemstones and other natural materials reputed to possess healing powers. Underneath, a salt-covered floor symbolises cleansing and ritual. The work suggests a rainbow, a vision of hope and new beginnings. The title refers to the Hindu god Indra, who used a rainbow to combat evil.

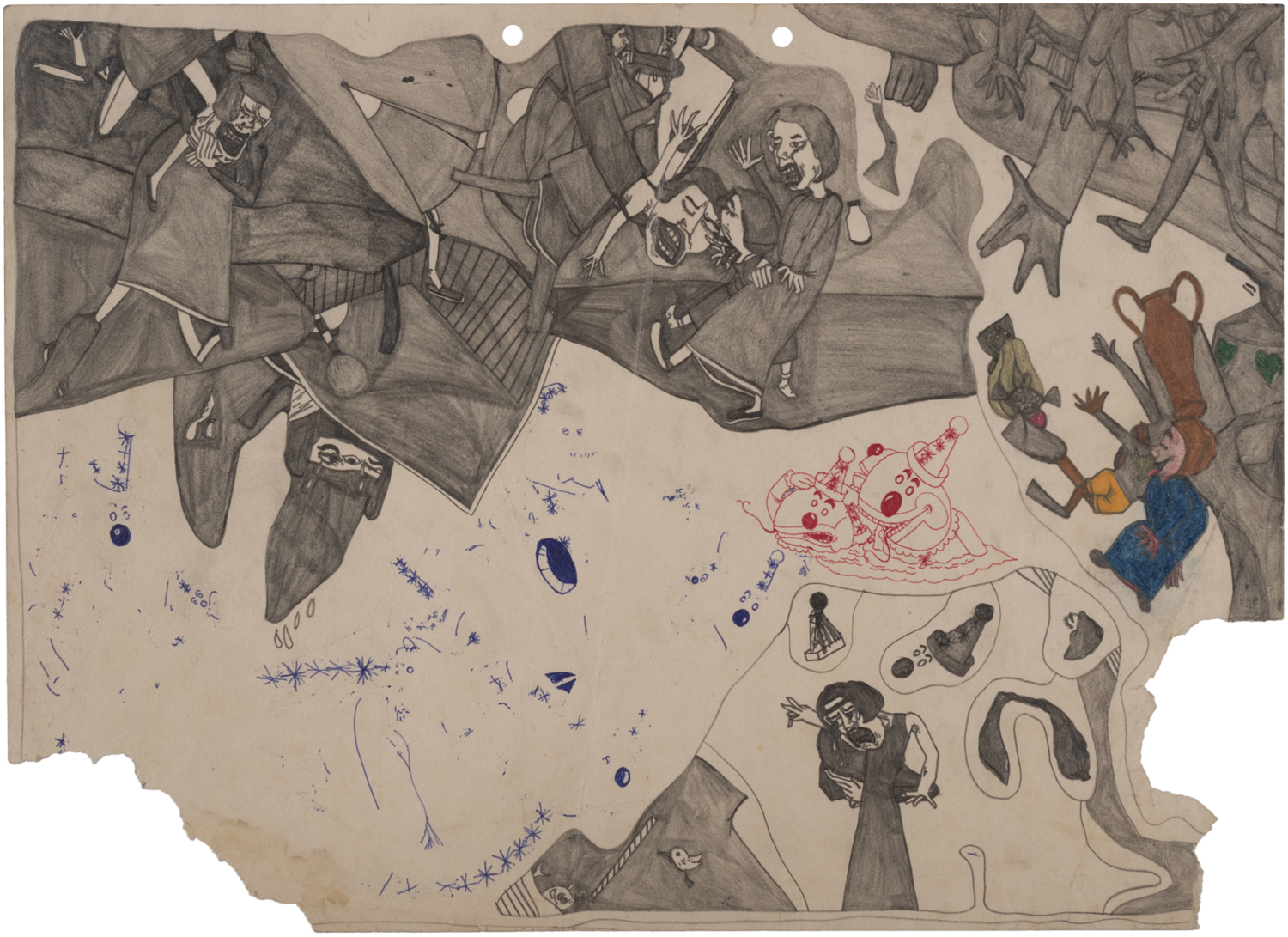

Singh’s other work, Total Internal Reflection (also 2018), is interactive. Visitors are invited to choose one of seven colours—keyed to the seven chakras in Hinduism and Buddhism—to reflect their mood. They then enter an empty gallery dappled with lights, mixing their colour with those others have chosen. This work, the artist says, prompts us to reflect on our place within a larger community. She likens the experience to standing in a cathedral, in the light cast through a stained-glass window.6

Locally, Singh has become the poster girl for art-wellness. She offers herself as a marquee-value ‘name’ artist, while engaging communities of participants in her endeavour, albeit in highly constrained ways—please pick a colour from the seven I have already picked for you. Her works, here and elsewhere, seem to offer a bridge between inclusive community art (everyone is an artist) and elite professional art (museum-worthy artists), but actually fudge the epic gulf between them.

Clearly, Singh struck a chord with Ardern. In an op-ed piece on the arts for the Herald in 2018, Singh is the only artist Ardern names, writing: ‘New Zealand-born Indian-Samoan artist Tiffany Singh describes what she does as “a tool for social change”. Her work explores the relationship between arts and culture and wellbeing by encouraging communities – or in the case of her 2013 project Fly Me Up to Where You Are, 15,000 school children from low decile schools – to contribute in some way. Art and wellbeing, the idea that creativity and joy should never be just the domain of the privileged few, but accessible to all, isn’t new, but hopefully it’s coming of age.’7

She adds: ‘Kiwis are also more likely than ever to believe the arts benefit our economy, our local communities, and our personal well-being. And we’re right to do so. There is a growing body of international research evidence to support this groundswell of opinion, with arts engagement being increasingly seen as an effective way to help manage the stresses and strains of this modern digital world. Studies show that for those with mental health issues—from anxiety and depression to neuro-degenerative diseases like dementia—art therapy can profoundly improve lives.’8

At Te Papa, Singh’s installations have now been up for three years. They tick predictable boxes—populism and participation; wellness and diversity; inclusion and kids—advertising Te Papa’s good-works mission. However, I haven’t found a ‘growing body of international research evidence’ that ribbon rainbows and coloured lights seriously address mental-health issues ‘from anxiety and depression to neuro-degenerative diseases like dementia’. The idea that such works ‘profoundly improve lives’ seems a stretch. Their emphasis is more on signifying wellness.

I can see why Adern would endorse Singh’s works, which are so on-message for the Government. And yet, it is odd for an arts minister to single out one rather atypical artist as the way forward for all. Singh’s wellness works operate in a niche area of art practice, hardly representative of art’s bandwidth. Most artists don’t make their art to fit public-health agendas. It is not what gets them out of bed. They have their own questions. Artists are not de-facto caregivers developing ‘cost-effective’ wellness works on the off-chance that they will be acquired for government-funded museums—although this might be the direction we are heading.

Interestingly, Te Papa—which has largely turned its back on overseas art, in favour of a national focus—has looked offshore for artists to produce works to fill Toi Art’s new double-height, grand-statements space. While not as overtly focused on wellness as Singh’s works, major commissions by Australia’s Nike Savvas and Japan’s Chiharu Shiota extend the wellness message.

For Finale: Bouquet (2019), Savvas suspended hundreds of thousands of bits of coloured plastic from nylon wires, filling two storeys of air with a pointillist mist – an effect similar to that of her 1996 installation Simple Division, in Auckland Art Gallery’s collection. In this case, however, her colour palette was partly inspired, we are told, by renderings of native New Zealand flora by historical artist Sarah Featon—a know-my-name/eco name-drop. Savvas’s work evokes endless bliss. As Te Papa’s website explains: ‘Finale: Bouquet … captures a moment of jubilation, with confetti caught mid-fall in a celebration that never ends.’9

And now, in the same space, Te Papa has just installed Chiharu Shiota’s somewhat darker The Web of Time (2020)—Arabic numerals suspended in a sublime spider’s web of string. It will be up for a year. According to Te Papa’s website, the work ‘draws on ideas of the cosmos, human existence, and the potential for the future … Shiota believes numbers act as a universal language and a shared concept of time, with the ability to … connect people.’10 The matrix! The optimistic Japanese artist explains: ‘All my work is inspired by my life or by a personal emotion. I try to expand this emotion into something universal to connect with others … In the past, I have had to overcome some serious medical conditions, and creating art has helped me to survive … Life will continue to push me.’11

Te Papa offers a case study of how wellness thinking is shaping art-museum practice across the sector. Singh’s two installations and these two big-investment, overseas-artist installations have much in common, thematically and formally. They are immersive walk-through or walk-past spectacles, courting the wow factor. They involve candy colours and/or miles of string (or similar). They suggest repetitive ordering as a calming activity, for artist and audience. They are easy on the eye and gentle on my mind, delighting children and the child in us all. They are affirmative and G-rated. In the current moment, artists who produce such chilled works will doubtless find favour with museums, not because they necessarily advance art practice but because they combine institutional virtue signalling with Instagram appeal. Indeed, Shiota’s exhibition includes a screen where visitors’ hashtagged selfies taken within her work pop up.

The road to hell is paved with good intentions. Ardern’s Herald article was titled ‘Why I want arts and culture integrated into all areas of New Zealand society’. It sounds like a great idea, and clearly Ardern wants to be a friend to the arts—and we need friends. But is it such a good idea to integrate the arts into all areas of New Zealand society? What would that look like? Isn’t this ‘integration’ simply code for harnessing art as a cost-effective tool to serve other state purposes, putting art to work? If art has value in and of itself, why integrate it into all areas? My issue here, then, isn’t with wellness as such. Wellness culture is part of this moment and there are rich veins of art addressing and exemplifying it—some pro, some con; some silly, some smart. Wellness clearly has a place. There is no problem in incorporating it into our thinking about art, as part of art’s diversity. But it is a big loss if we fixate on wellness as the necessary be-all and end-all of art and its institutions at the expense of that diversity—if we can’t tell the difference.

.

[IMAGE: Tiffany Singh Total Internal Reflection 2018]

.

- These justifications have become routine. For instance, Creative New Zealand’s website asserts: ‘The arts contribute to New Zealand’s economic, cultural, and social well-being. We know and have proof [that] the arts: contributes to the economy; improves educational outcomes; creates a more highly skilled workforce; improves health outcomes; [and] improves your personal well-being. And the arts … rejuvenate cities; support democracy; create social inclusion; [and] are important to the lives of New Zealanders.’, www. creativenz.govt.nz/development-and-resources/advocacy- toolkit/the-evidence-for-advocacy.

- Alain de Botton and John Armstrong, Art as Therapy, Phaidon, London, 2013.

- Carl Cederström and André Spicer, The Wellness Syndrome, Polity Press, Cambridge and Malden MA, 2015.

- Dionne Christian, ‘The Art of Making Us a Healthier and Happier Nation’, Herald, 3 April 2019: www.nzherald.co.nz/entertainment/the-art-of-making-us-a-healthier-and-happier-nation/G3KFG7MEY3LSUOTMRZZP2TZWE4/.

- See www.tepapa.govt.nz/about/news/2018-news/art-vital-part-our-lives-jacinda-ardern-open-toi-art.

- Te Papa’s wall text for Total Internal Reflection reads: ‘How are you feeling? This experimental installation invites you to choose a colour based on how you feel right now. Press a button and become part of an evolving light sculpture. Artist Tiffany Singh believes engaging with the arts can improve physical and mental health. She intends Total Internal Reflection to be a dynamic “responsive environment” that expresses our collective wellbeing through colour.’ See www.tepapa.govt.nz/visit/exhibitions/toi-art/tiffany-singh-indras-bow-total-internal-reflection.

- Jacinda Ardern, ‘PM Jacinda Ardern: Why I Want Arts and Culture Integrated into all Areas of NZ Society’, New Zealand Herald, 23 May 2018: www.nzherald.co.nz/entertainment/ pm-jacinda-ardern-why-i-want-arts-and-culture-integrated- into-all-areas-of-nz-society/RX67ZXPXUKXQG4AM5M- 6J3W6VRE/.

- ibid.

- See www.tepapa.govt.nz/about/past-exhibitions/2019-past-exhibitions/nike-savvas-finale-bouquet.

- See www.tepapa.govt.nz/about/press-and-media/press-releases/2020-media-releases/chiharu-shiota-brings-her- spectacular-two, accessed 11 February 2021. Similarly, the wall text says: ‘ “I want the viewer to reflect on their inner self, on their life—past, present, and future …”—Chiharu Shiota. Enter a vision of the universe. In The Web of Time, countless intertwined strands connect numbers across time and space. These numbers—scattered like stars in the night sky—represent meaningful dates in history, both collective and personal. Berlin-based artist Chiharu Shiota says, “Numbers comfort us. We share dates that are important to us, and they help us understand ourselves.” ’

- T.F. Chan, ‘At Home with Artist Chiharu Shiota’, Wallpaper, 1 June 2020: www.wallpaper.com/art/at-home-with-artist- chiharu-shiota.