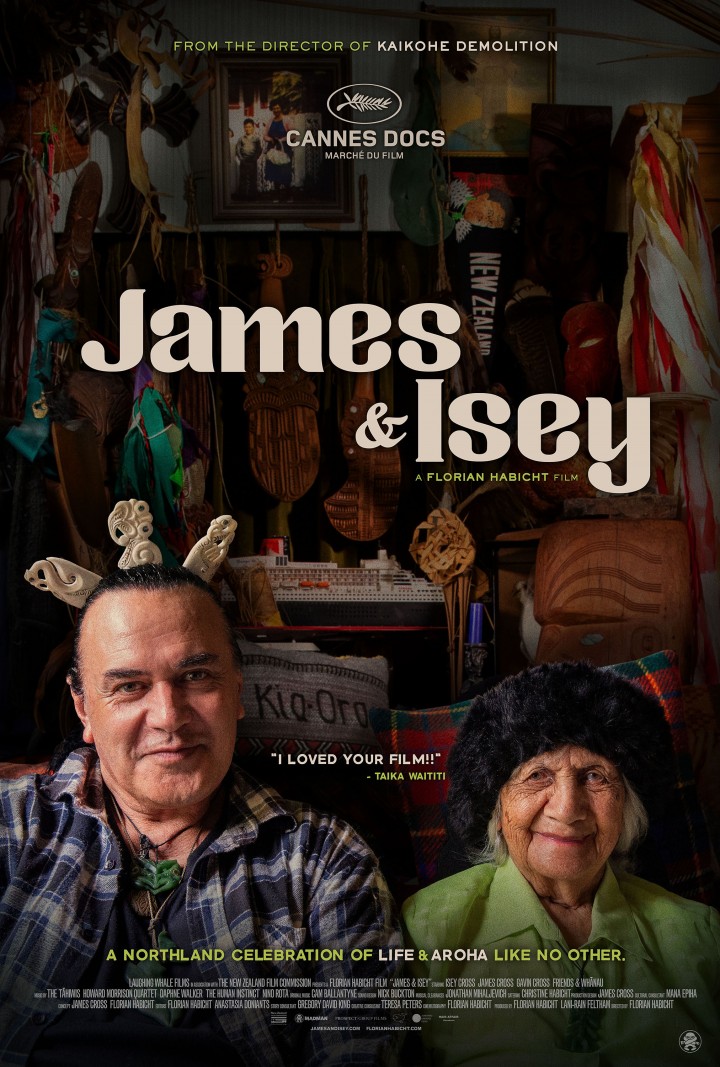

Art News, Spring–Summer 2021.

.

Dame Robin White is having a moment. At seventy-five, she’s busier and more visible than ever. A White retrospective—curated by Sarah Farrar, Nina Tonga, and Jill Trevelyan for Wellington’s Te Papa and Auckland Art Gallery Toi o Tāmaki—opens next year, accompanied by a big book. White has just had a solo show, Aio Ngaira (This Is Us), at Wellington’s McLeavey Gallery. She’s one of sixteen senior women artists currently showcased in Another Energy: Power to Continue Challenging at Tokyo’s Mori Art Museum. And she’s one of four artists exploring Henri Matisse’s legacy in Matisse Alive, on now at Sydney’s Art Gallery of New South Wales—a sidebar show to their Matisse: Life and Spirit blockbuster from the Pompidou. Curator Justin Paton says, ‘we invited Robin for three reasons: her deep sympathy as a painter for Matisse, her unique perspective on him as a visitor to the Pacific, and, above all, the sheer beauty and wisdom of the art she is currently making—the richest in a remarkable career.’

White has come a long way. Through the 1970s, she was an exemplary regional-realist painter, creating iconic New Zealand images. Alongside Michael Smither and Don Binney, she updated Colin McCahon and Rita Angus’s Pākehā nationalist-pioneer-settler art idea for a new generation. (Although White is Ngāti Awa on her dad’s side and attended Ngā Puna Waihanga conferences, this wasn’t explicitly reflected in her work and largely passed without comment.) Her rural landscapes featured rolling green hills, clear blue skies and seas, and isolated buildings—colonial wooden houses, churches, and tiny railway stations. Her portraits presented friends and family as stoic, salt-of-the-earth types. Her plain-speaking, frontal compositions and crisp, clean, idealising aesthetic would translate beautifully into the logic of the screen prints that popularised her vision. The title of her 1981 monograph said it all: Robin White: New Zealand Painter.

But things would change, dramatically. In 1982, White—who had embraced the Baháʼí faith of her parents—responded to a call to support the emerging Baháʼí community in the Republic of Kiribati, formerly the Gilbert Islands. (They call it ‘pioneering’.) She and her family decamped to the remote atoll of Tarawa. If her work had celebrated a simple life in New Zealand, her life would get even simpler. She quickly abandoned the complexity of oil painting and screen printing to focus on making wood-block prints. Her new work responded to her new location: Beginner’s Guide to Gilbertese (1983) was about learning the local language and the diaristic Twenty-Eight Days in Kiribati (1985) was about showing visiting New Zealand friends her new home. Had White turned her back on her established career, her brand? Her work was still about place, but now a different one. In 1984, after her first show with him since departing, her dealer Peter McLeavey wrote to her, acknowledging that collectors preferred her earlier New Zealand ‘ikons of place’, but reassuring her that ‘soon, the tide will turn’.

In 1996, a fire razed White’s home and studio on Tarawa, but it proved to be a blessing in disguise, as she would later see it, quoting Baha’u’llah: ‘My calamity is My providence.’ As an artist, White was forced to turn to what was available on her doorstep, engaging local weavers to convert her designs into pandanus-leaf placemats. New Angel (1998)—based on logos for basic products available from the island’s local stores—conflated commercial pop imagery with customary weaving, the imported and the homegrown. It played on latent religious symbolism: Instant Sunshine (milk powder) and Paradise Twist (tobacco), Fresh Bread and New Angel (tinned mackerel). Loaves and fishes! In White’s works, the humble proves portentous.

New Angel set White on a new path. Collaborating with Pacific Island women artists would become her MO. This would continue—indeed, rev up—after she returned to New Zealand in 1999, settling in Masterton, farming heartland, an hour’s drive from the ocean, the farthest from it she had ever lived. White had long admired ngatu (painted tapa cloths), particularly some fine examples hanging in Fiji’s Nadi Airport. In 2000, a Baháʼí friend, Leba Toki, agreed to teach her. Ngatu are created using a variety of techniques. Sometimes, patterns and images are transferred using relief rubbing plates (kupesi) placed under the cloth; other times they are directly stencilled on. White related to such techniques from her background in screen printing. She would go on to make Teitei Vou (A New Garden) (2009) with Toki and Bale Jione for the Asia Pacific Triennial in Brisbane in 2010. It presented a utopian image of ‘Sugar City’, conflating Lautoka, in Fiji, and Mt Carmel, the administrative centre of the Baháʼí faith in Israel, with many allegories integrated into the scheme. In 2010, at a Baháʼí summer school in New Zealand, White met Ruha Fifita, a young Tongan woman studying at QUT in Brisbane. They collaborated on ngatu that were presented in Kermadec (City Gallery Wellington, 2012) and Ko e Hala Hangatonu: The Straight Path (Pātaka, Porirua, 2014), often working with the women of Haveluloto village on the execution. Recently, she has been working with Ruha’s sister Ebonie and others.

White’s eclectic ngatu combine different traditions (Fijian and Tongan), and drew their imagery from here and there. They bridge the customary and the contemporary, the individual and the collective. While they have a cross-cultural dimension, they are also a product of the artists’ common Baháʼí faith, which stresses a fundamental human unity underpinning cultural diversity. As Baha’u’llah said: ‘The Earth is but one country, and mankind its citizens.’ Describing her work with Toki, White has said: ‘By using tapa to convey designs that include recognisable Indian and European elements, we aimed at suggesting the possibility of one culture embracing, in a positive way, features of other cultures, and that this process generates change without necessarily compromising the essential values that form the basis of a secure sense of identity and belief.’ White’s collaborations operate on multiple levels. Sometimes, her ngatu are designed and executed with others, but, increasingly, as with the works in Matisse Alive, she is responsible for the designs, bringing in others on the execution. She has also found new ways to collaborate. In 2019, she started working with Taeko Ogawa from Hiroshima, who generates avant-garde calligraphy to incorporate into White’s designs.

•

White has now been back in New Zealand for longer than she was in Tarawa. When she left her homeland, she seemed to close one chapter of work (to do with a settler aesthetic), ultimately opening another (engaging with Indigenous cultures of the Pacific). But perhaps these phases of her work have more in common than is immediately apparent. When curator Justin Paton commissioned White to respond to Matisse’s engagement with the Pacific for Matisse Alive, it was an opportunity for her to reflect on her own engagement with the Pacific through the work of her French predecessor.

Matisse was inspired by exotic locations. Early on, trips to French colonies—Algeria in 1906 and Morocco in 1913—proved decisive in the development of his art. In 1930, at the age of sixty, he spent three months in French Polynesia, including two months chilling out in Tahiti. He was on holiday. He didn’t make much work: one small painting, some drawings, a few snaps. ‘I came back from the islands empty handed’, he confessed to Brassaï. However, impressions of the place—of its light and lagoons, its flora and fauna, its tivaevae—would percolate in his memory. A few years later, he made two paintings based on the view through his hotel window in Papeete (Window in Tahiti I, 1935, and II, 1936). But it wasn’t until 1946 that the memories would fully kick in, inspiring his iconic silk-screened hangings, Oceania, the Sea and Oceania, the Sky. It was the start of his most radical work, the cutouts, which sustained him until the end.

In preparation for her project, White read books: Hilary Spurling’s Matisse biography, Paule Laudon’s Matisse in Tahiti, and the exhibition catalogue for the 2017 Matisse in the Studio exhibition at London’s Royal Academy, which charted the ways Matisse employed domestic objects as ‘actors’ in his paintings. In Pierre Courthion’s Chatting with Henri Matisse, she noted a passage: ‘He knows his props and he knows how to arrange them. Already, the armchair, the table, the chairs, everything around him seems to have taken the impress of his personality.’ For the Sydney show, White decided to make interiors, studio scenes, as settings for imagined conversations, where objects owned by Matisse and others would stand in for them, as if impressed with their personalities.

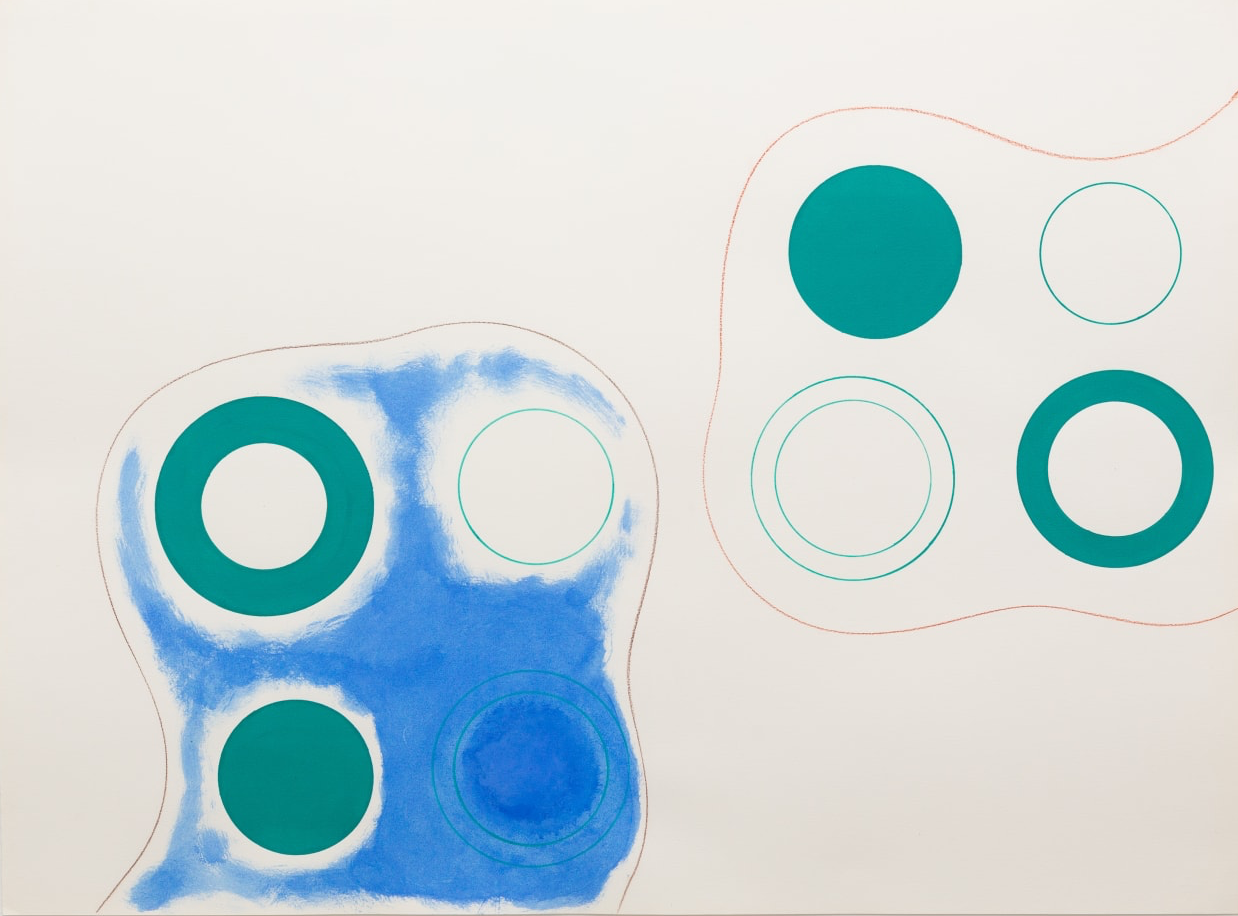

Assisted by EbonieFifita and other helping hands, she produced four ngatu for the show. The largest of these, the widescreen Vaiola addresses Matisse’s response to the light he saw in the ocean at Fakarava (vai means water, ola light or life). From within a ngatu-lined room, we glimpse stylised-patterned ocean waves through two sets of windows—although these could also be framed pieces of ngatu. White references Matisse’s Window in Tahiti paintings, where the window also features a drawn curtain.

In Vaiola, two wooden chairs—based on chairs from White’s home in Masterton—wait for people to meet and converse. Matisse? And who? A coffee pot, cups, shells, and a pineapple—White’s versions of items familiar from Matisse’s still lifes—rest on a table between them. On the far left are Matisse’s shoes and hat, copied from a photo taken the day he arrived in Papeete. His shoes sit on the floor; his hat is above them, half in and half out of the picture, overlapping its decorative border—perhaps hanging on it, perhaps flying free.

There’s also a gridded band of repeated images of a stylised bird. White says they were based on the white-dove crest of Ikale Tahi, the Tongan rugby team, but turned into ngongo (seabirds). One seems to have escaped, and is hiding in the pattern of the ngatu lining the wall. It’s hard to tell whether we are to read this band of birds as part of the interior or a decorative border around it. Along the top, ‘Vaiola’, a poem by ‘Akesa Fifita—Ruha and Ebonie’s grandmother—runs as another margin and border. The work plays games with windows and frames, and frames within frames; with borders, margins, and thresholds. As a ngatu that depicts a ngatu-lined interior, it’s a mise-en-abyme.

If Matisse fancied Tahiti as idyllic unspoiled nature, Vaiola quietly contradicts this. Palm corned-beef logos crown both sets of windows. The logo—showing a sun setting over the ocean, glimpsed through parted palms—evokes an island paradise. This logo has become a local icon; however Palm is not from the islands. It’s a New Zealand brand exported to the islands, where the fatty, salty meat has become a loved but problematic staple of the local diet, contributing to the decline of the local fishing industry and rampant obesity. The logo’s presence suggests how the islands are seen by outsiders, but also how their gaze might also be accepted and integrated by insiders. (Matisse scholar John Klein has observed a parallel case of misrecognition. Tivaevae had a massive influence on Matisse’s cutouts, yet these ‘indigenous’ designs were already informed by fabrics manufactured in Europe for the island market, based on colonialist assumptions regarding native taste.)

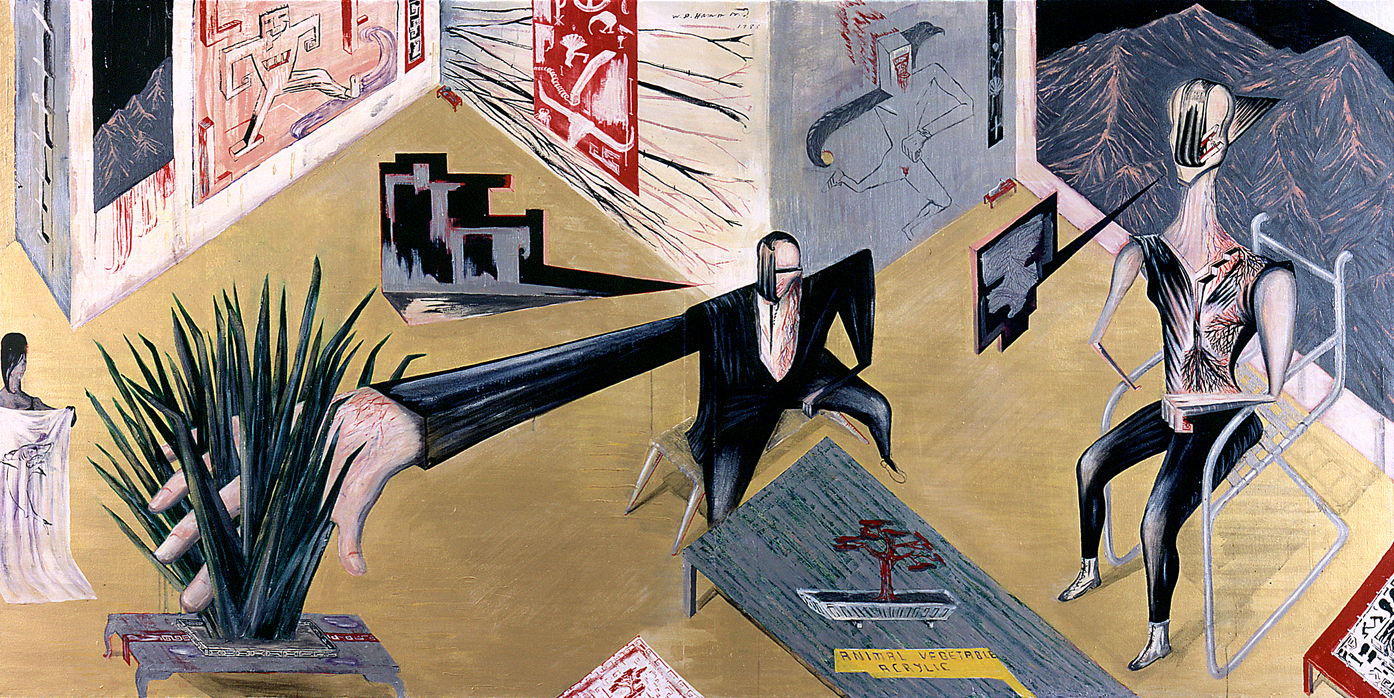

Matisse was hardly the first Westerner to head to Polynesia. He knowingly travelled in the footsteps of Paul Gauguin and Scottish novelist Robert Louis Stevenson. White’s Soon, the Tide Will Turn is based on the Tapa Room at Villa Vailima in Sāmoa, where Stevenson lived from 1890 until his death in 1894. Now a tourist attraction, the Tapa Room is a mélange of the colonial and the local, here and there. While its walls are lined with ngatu, there’s also a fireplace. It was totally unnecessary, given the climate, but Stevenson had it built anyway, as a symbolic hearth—home away from home. In her work, White includes Stevenson’s fireplace, his oval mirror, and a local weapon hung as an objet d’art. European-style floral drapes frame the scene, perhaps contrasting with the ngatu, perhaps akin.

This set is occupied by the notorious chaise longue that dominated McLeavey’s Wellington gallery for decades, standing in for him, even after he died. The work’s title, of course, quotes McLeavey’s advice to White. Alongside the chaise is a wooden chair (one of White’s, from Masterton). Together, chaise and chair suggest a psychoanalytic session, and McLeavey did enter analysis. Matisse’s hat rests on the chaise, while his shoes are parked under the chair. McLeavey’s kete leans against the chaise, and perhaps those are his notebooks on the floor. On the mantelpiece, White has arranged a shell (perhaps a reference to Tahitian shells in Matisse’s still lives), two gas lamps (which could be original to Villa Vailima, but could also be a McCahon reference), and a hand-sanitiser dispenser (recalling the soda-water siphons in the Tapa Room, but updated as a nod to Covid). White is also present in the tableau. Hung over the ngatu-lined wall is a framed picture recalling Mangaweka, a screen print White made in New Zealand in 1974. Displaced, it reads as an exotic curio, a souvenir of another time and place.

White’s suite of works stages a complex conversation between departed souls—who never met, and who never could meet, because they occupied different historical moments (Stevenson, Matisse, and McLeavey). But the conversation also includes the living (White, Ebonie Fifita, and ‘Akura Fifita). In the third ngatu of a ngatu-lined interior, To See and to Know Are not Necessarily the Same, White incorporates a calligraphy design by Ogawa—a fellow Matisse fan. It presents a Chinese proverb: ‘When you drink water, think of the source.’ Ogawa’s design is a nod to the Chinese calligraphy panel Matisse’s wife gave him for his sixtieth birthday, which features in numerous photos of him and his studio.

A fourth work, a ngatu ‘uli (black ngatu)—Hufanga‘anga—completes the room. Made using a black dye from the soot of burned tuitui (candlenuts), ngatu ‘uli are difficult to make, highly valued, and associated with Tongan royalty. Hufanga‘anga (meaning sanctuary) is a big, solid-black rectangle surrounded by an ochre border. White calls it a ‘portal’, and compares it to Matisse’s windows. It hangs vertically, like a door, as a threshold between here and there. This abstract ngatu sits in the company of three highly illustrative and decorative ones, yet all four suggest spaces the viewer could step into.

While Matisse is a constant reference point in these works, they are hardly Matisse like. Where are the blocky colours, the free expressive lines, and the nature focus we associate with Matisse’s Pacific works? While celebrating Matisse, White prefers interiors, prioritises culture, and adopts a dark palette of blacks and browns. Her manner also holds ngatu tradition at arm’s length. While ngatu are generally pattern based, White’s are increasingly like pictures. Her outline drawing delineates forms in space, even if the outlines are ‘snapped to grid’ and filled in with flat patterns, generating a push–pull between 2D and 3D. The approach recalls White’s early screen prints, which also involve meticulously deconstructing an image and patiently reconstituting it, step by step. As with the screen prints, much of the appeal here lies in seeing how the logic of the process has become implicit in the final image.

White’s Matisse works have a magical, uncanny dimension. She says they belong to ‘the fluid yet episodic world of dreams’, which may explain the jumbled time frames and prompt us to hunt for hidden meanings, like psychoanalysts. One tell-tale correspondence catches my eye. In Soon, the Tide Will Turn, an ambiguous form—a black rectangle with an ochre border—is reflected in Stevenson’s mirror. The shape could be a window (one is reflected in the mirror in photos of the Tapa Room I found online). It could also be a door. Or it could be Hufanga‘anga itself, which, at the Art Gallery of New South Wales, hangs nearby. Beside the mirror is White’s nod to her Mangaweka print. In it, the building’s front door—a black rectangle with an ochre border—echoes the form reflected in the mirror. When I compare it with the actual Mangawaka print, I see White has removed the ute from in front of the building to offer us an unimpeded view of that door. Is this visual rhyme a secret message or a red herring; a deliberately baited hook, an unconscious Freudian slip, or serendipity?

And, with this show, when and where are we anyway? Are we in White’s home in Masterton with her wooden chairs or in McLeavey’s Gallery in Wellington with his chaise, in Stevenson’s mansion above Apia or in Matisse’s studio in Nice? Are we somehow in all these places and moments at once, confounding the issue of who is guest and who is host? Riddled with portals, actual and metaphorical, these works emphasise the porousness of cultural spaces—suggesting opportunities to come and go, physically, psychologically, culturally.

White’s project speaks to our current moment, which demands cultural engagement but is fraught about cultural appropriation. White is not fraught. She embraces Stevenson and Matisse as fellow travellers, who passed through the Pacific with open eyes and hearts, and were positively transformed by the experience. When asked if she identifies as Māori, Pākehā, or Pacific Island, she dodges the question, replying either ‘I’m a hybrid’ or ‘I’m a Baháʼí’. Her approach is in sync with a Baháʼí world view that asserts a fundamental unity underpinning human diversity, and that understands religions—which frequently find themselves at war—as part of a common faith. Her ngatu express this through how they are made and how they are—means and ends. With their decorative quality, they transmute pictorial principles of balance and integration into an ethic or politic of peace and civility, absorbing and managing multiplicity, downplaying discord. ‘Difference without opposition’, as art critic Craig Owens once put it. At a time when division is our default setting, White offers a work around.

For me, so much turns on that one detail: White discovering her Mangaweka print—that fragment of her past life—hanging in the Tapa Room alongside the charged remnants of other kindred spirits who passed this way. In this humble detail, White’s early insular settler New Zealand ethos reaches out to, holds hands with, and is incorporated into her new Moana cosmopolitanism, suggesting how much things have changed, how much they remain the same. Or am I dreaming?

.

[IMAGE: Robin White Soon, the Tide Will Turn 2021]