Julian Dashper & Friends, ex. cat. (Wellington: City Gallery Wellington, 2015).

‘The museum wants the artist timeless. It is waiting for the death. Only with the closure of death does the oeuvre completely and happily begin.’ So wrote art critic Francis Pound in 1991, in a catalogue essay for the then-young artist Julian Dashper.1 His words returned to haunt us on 30 July 2009, when Dashper died from melanoma, aged just forty-nine. Julian Dashper & Friends is a tribute to this key New Zealand artist and a response to the question of how to represent him, in retrospect.

As a self-consciously art-historical artist, Dashper’s works were always in dialogue with other artists and with art history. So, in Julian Dashper & Friends, I present his works ‘in conversation’ with works by other artists—older artists, his contemporaries, and younger artists. This reflects Dashper’s own practice of making two-person shows and curating other artists into his ‘solo’ shows.

Julian Dashper & Friends includes important artists. In addition to Dashper, there’s Rita Angus, Billy Apple, Daniel Buren, Fiona Connor, Colin McCahon, Dane Mitchell, Milan Mrkusich, John Nixon, John Reynolds, Peter Robinson, Marie Shannon, Imants Tillers, Peter Tyndall, Jan van der Ploeg, and Gordon Walters. But the list is indicative, not exhaustive. There are other dimensions and artists I could have explored. I would have loved to include Donald Judd. (I tried, I really tried!) As large as it is, our show remains a sketch.

.

TIME AND PLACE

.

Dashper was an artist of his time and place who reflected on his time and place.

He studied at Auckland’s Elam School of Fine Arts from 1978 to 1981. He would often list two of his tutors there as early influences. They were diametrically opposed: Philip Clairmont, the old-school expressionist, and Billy Apple, the visiting expat pop-conceptualist. Back then, the local discussion was dominated by the nationalism/internationalism debate. During the 1970s, the New Zealand painting mainstream had been challenged by two kinds of internationalism: abstraction and conceptualism (post- object art, we called it). However, internationally, in the early 1980s, both would be eclipsed by neo-expressionism (via Dashper’s namesake—the American, Julian Schnabel). Dashper would go on to explore and scramble all these idioms—the New Zealand art mainstream, abstraction, conceptualism, and neo-expressionism. Although his first solo show was a post-object-art installation,2 in the 1980s he would make his name as a neo-expressionist painter. By the end of the decade, however, he would have ditched painterly spatter. He went on to work in an increasingly cool manner, mixing up abstraction and conceptualism.

Dashper took liberties. He was forever riffing on other artists’ works, but putting his own spin on things. His homages were perverse, because they did not address his elders through their central achievements, but approached them obliquely. Although Dashper referred to major international figures, including Barnett Newman and Edvard Munch, his citations of local heroes, like McCahon, Angus, Walters, and Michael Smither, would seem more poignant and pointed, given the peculiar intimacy of the local scene.

Dashper also made works addressing the conventional nature of art’s supports and supplements, the things in art that we typically consider beside the point, not ‘the work itself’. These included behind-the-scenes stuff (gallery spaces, packaging materials, hanging systems, documentation) and front-of-house stuff (advertising, exhibition signage, catalogues, art magazines, ads and reviews, his CV).

Dashper’s work was full of in-jokes. For outsiders, it could seem dry and arcane. But for those whose business and pleasure was the art world and its machinations, it was witty and consequential.

1992 was the crucial year. An inaugural QEII Arts Council Fellowship enabled Dashper to quit taxi driving and to go full time as an artist. His exhibition practice expanded dramatically. That year, he had seven solo shows, presented an ambitious magazine project in Artforum, created the five drum-kit installations that would become known as The Big Bang Theory, and starred in the exhibition Headlands: Thinking through New Zealand Art at the Museum of Contemporary Art, Sydney. As one of the curators, I can say that his work was not only included in Headlands, it informed the show’s whole revisionist attitude and cheeky tone.

After that, Dashper increasingly looked offshore. He became a frequent flyer. In 1993, he had his first overseas solo show, at Melbourne’s Store 5. Later, he would regularly exhibit in Europe and America. He showed in museums and with dealers, but also utilised a network of internationally dispersed artist-run spaces, often those devoted to non-objective art (‘artists’ clubhouses’, artist Simon Ingram calls them). As he sought to locate his work in an international discussion, he largely jettisoned his references to New Zealand art, instead weaving his mixed messages out of tropes drawn from abstraction and conceptualism.

Dashper represents the end of something and a beginning. When he started out, New Zealand art was a more-or-less enclosed discourse; our artists rarely showed overseas. By the time Dashper died, our young artists were studying offshore and enjoying international residencies, and New Zealand was participating in the Venice Biennale. Dashper paved the way for a brave new generation of New Zealand artists to operate internationally. For New Zealand, he represents a transitional figure, a bridge between the insular, nationalist, medium-based art that preceded him and the globe-trotting, post-national, post-medium art that followed.

.

PERVERSE HOMAGES

.

Dashper’s perverse homages had a precursor in Colin McCahon. Operating in New Zealand, in splendid isolation, McCahon worked his way through art history, on his own terms. His citations were self serving. For instance, his cartoon-like Entombment (After Titian) (1947) was the antithesis of Titian’s painterly sensuousness, his Bellini Madonnas (1961–2) looked more like suprematism, and his abstracted Waterfalls (1964–6) would never have been confused with those of William Hodges.

McCahon’s Here I Give Thanks to Mondrian (1961) was particularly odd. Piet Mondrian was the purest-of-pure abstract painters. McCahon had seen his work during his 1958 trip to the US. However, for McCahon, art needed to have a message and pure abstraction risked being vacuous. In 1972, he wrote: ‘Mondrian, it seemed to me, came up in this century as a great barrier—the painting to END all painting. As a painter, how do you get around either a Michelangelo or a Mondrian? It seems that the only way is not more “masking-tape” but more involvement in the human situation.’3 Here I Give Thanks to Mondrian was not so thankful or so Mondrianesque. It was, rather, anti-Mondrian: in it, McCahon painted diagonal lines, used a creamy-beige-and-black palette, and conjured up a landscape space. It was McCahon processing his anxieties about abstraction in general, Mondrian in particular.

If Mondrian was a problem for McCahon, McCahon would be a problem for the New Zealand artists that followed him. Like Mondrian, he came to represent ‘the painting to end all painting’, someone to ‘get around’. He may have been a model for Dashper’s perverse homages, but he would also be a target of them. Dashper’s Here I Was Given (1990–1) is a McCahon pastiche. Dashper attached pieces of fabric, tape, and cord to three picture frames. In addition to echoing the composition of Here I Give Thanks to Mondrian, Here I Was Given refers to McCahon’s interest in frames, his use of unstretched canvas, and his provincial understanding of abstraction as landscape. Although Dashper carries over these elements from McCahon, the effect is different. Dashper has his fun with McCahon’s ideas and imagery, but drains them of gravitas, metaphysical pretensions, and religious implications. That Dashper could do this in the early 1990s demonstrated not McCahon’s ongoing relevance but his new irrelevance. His treatment of McCahon was not unique. After McCahon’s death in 1987, other artists got over him by doing impressions.

.

Dashper’s Here I Was Given may look like McCahon’s Here I Give Thanks to Mondrian, but Dashper’s homages to Rita Angus barely resemble her works. In 1989, Dashper produced a series of paintings that referred to Angus’s AD 1968 (1968). In this magic-realist painting, things she had recently seen (some clouds, a bit of driftwood, seahorses, and oil tanks) were arranged to spell out the date—‘AD 1968’. Ron Brownson believes it was a ‘monument’ to her father, who died that year.4 Dashper’s paintings, however, did not represent the year they were painted. Most were of ‘1960’, the year of his own birth. Although they referred to Angus, their style barely resembled hers and they had nothing to say about her. The numbers were drawn in a decorative style, but were not represented through objects. Drafted using French curves, they suggested Walters as much as Angus. Was Dashper testing how oblique and pointless references could be? In our show, we have a 1989 ‘1960’ painting. We also have a 1989 ‘1982’ painting, titled Nineteen Eighty-Four. Perhaps Dashper just wanted to infuriate art historians and fact checkers.

.

Dashper’s homages did not necessarily celebrate the artists they referred to. For his Murals for a Contemporary House (1988), he painted gridded geometries on absurdly fat, square canvases. He hung these canvases on clunky freestanding room partitions, upholstered in a retro fabric and resting on blocky feet. Curator Christina Barton put one into her 1989 Auckland City Art Gallery show After McCahon, noting their similarity to McCahon’s 1950s works. However, the Murals could have been related to works by other artists of the day. In his review of After McCahon, critic Francis Pound lamented the McCahon connection, arguing that the Murals were more akin to Gordon Walters’s 1950s work and observing that the culture’s obsession with McCahon came at the expense of Walters and full-blown abstraction.5 For Pound, Dashper’s work should have been a feather in Walters’s cap, not McCahon’s.

The canon is constantly being rewritten in and for the present. Young artists confer status upon their elders by citing them. Pound called this ‘canonisation from below’, taking Dashper’s (supposed) nods to Walters as an example.6 But, here, in coopting the younger artist, Pound overlooked something crucial. Any similarity between Dashper and Walters was skin deep. The Murals may look like Walters’s work, but they belong to a different paradigm—a conceptualist post-formalist one, which has left Walters behind. Dashper quickly mocked up a 1950s-period look, but, in the 1950s, Walters was patiently grail-questing for some ineffable formal rightness. In paying homage, Dashper addressed the past only to distance himself from it.

In our show, Dashper’s Mural 2 is hung alongside a classic 1950s abstraction, Milan Mrkusich’s Head (1955), and a late Walters, Construction with Pale Blue (1989), painted a year after Dashper’s Murals. Instead of going for a 1950s Walters, I went for a late one, where Walters was himself looking back to his work of the 1950s, quoting himself as much as Dashper was. But there’s a big difference. That late Walters is a formalist work painted in a post-formalist moment.

.

CANON FODDER

.

In 1992, Dashper developed the ultimate expression of his perverse-homages idea. He made five site-specific installations, placing drum kits bearing the names of canonical figures of mainstream New Zealand art in towns associated with them. They suggested tribute bands. There was The Woollastons in Wellington, The Drivers in New Plymouth, The Anguses in Christchurch, The Hoteres in Dunedin, and The Colin McCahons in Auckland. The kits weren’t much in themselves, but their placement released associations latent in the sites. While the installations were often seen as celebrations of the mainstream canon, they were in a hostile idiom—post-object art. Had Dashper come to praise his subjects or to bury them? Later, he would dub the project The Big Bang Theory.

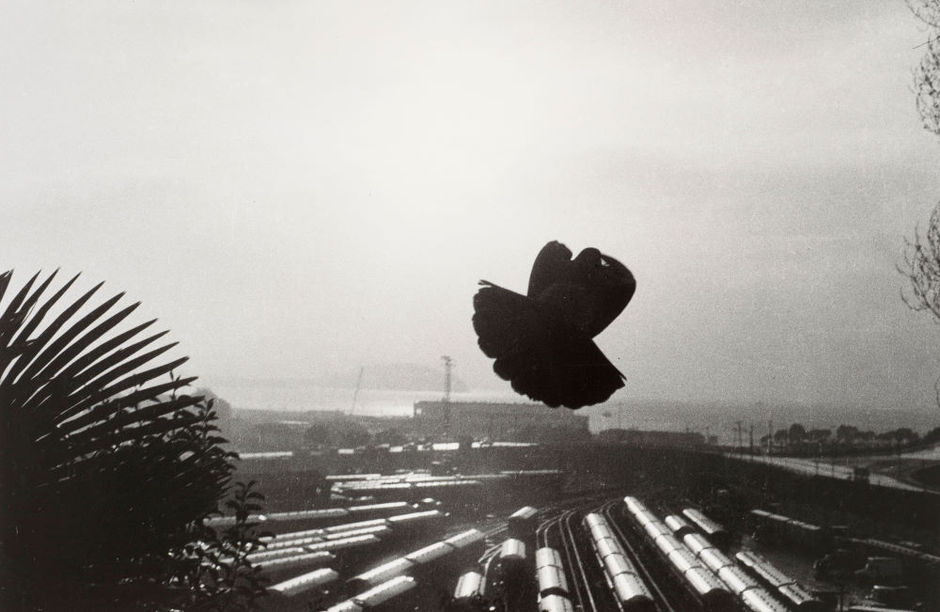

Dashper wanted to present The Colin McCahons at Auckland Art Gallery. The Gallery is heavily associated with McCahon—New Zealand’s most important artist. He had been a curator there. They had staged several retrospectives of his work and held lots of his work in their collection and on loan. The Gallery derived much of its authority from their connection with him. However, when the young Dashper had the presumption to ask to set up and photograph his The Colin McCahons kit in one of the Gallery’s galleries, the powers-that-be said no. So, he went rogue. He rented a supplementary space, the Gallery’s auditorium, set up his kit on the stage, and photographed it. Dashper could say it was shown in the Auckland Art Gallery, even if it wasn’t part of the official programme. The installation was seen by Dashper, his photographer, and one expert witness, art-history professor Tony Green. Apart from that, there was no audience.

In The Big Bang Theory, Dashper played on the inside-out question: Where does the work end and the world around it begin? What is content and what is context? Later, Dashper re-presented the drum-kit works as the drum kits themselves (out-of-context relics) and as photos of the original installations (documents showing the kits in context), begging the question as to which represented the idea better. Where was ‘the work’? In our show, The Colin McCahons is presented in both forms.

.

Dashper and John Reynolds met at Elam in 1978, Reynolds’s last year, Dashper’s first. In the 1980s, they shared a studio and often exhibited together. They were a dynamic duo. Their big, brash, painterly paintings tapped the neo-expressionist zeitgeist.

In 1986, at Wellington’s Peter McLeavey Gallery, they famously produced a collaborative painting, in situ. Dashper started on the left-hand side of the triptych, Reynolds on the right, and they met in the middle. The work’s title, Omaha Beach, could have referred to the beach north of Auckland or to the Allied invasion of occupied France during World War II. (Was this nationalism or internationalism?) Both artists later dropped the neo-expressionist approach and took different directions.

The Reynolds in our show is not from that neo- expressionist moment. It was made much later. Works End (2008) references the canon of New Zealand art history, as Dashper did in The Big Bang Theory. It is not a painting, but a vast, commercially fabricated road sign. Instead of placenames, it bears the titles of the ten most expensive New Zealand art works sold at auction in then-recent years. They become a found poem. The works’ rankings are indicated by numbers, rendered as state-highway insignia. People will recognise some titles, but not all. Let Be, Let Be is clearly a McCahon, but who will know that Mount Cook and the Southern Alps is by Nicholas Chevalier or that No. 2 is McCahon’s No. 2? It’s a quiz! Works End has been shown indoors and out, but operates best in a gallery, where it can be mistaken for a functional piece of wayfinding. If previously we lived in a real landscape, where signs pointed to real locations, today we operate in a cultural landscape, where signs only point to other signs. Postmodernism 101.

.

THE ARTIST IN HIS STUDIO

.

Photographer Marie Shannon also met Dashper in 1978, when they were both in their first year at Elam. They became an item. Their son Leo was born in 1996. Dashper and Shannon made very different kinds of art, but they shared a playful attitude. Dashper’s pet name for her was Brains.

Over the years, Shannon has made many works referring to Dashper and their relationship. In the early 1990s, she made parody portraits, replacing her real-world subjects with generic pipecleaner figures. They were ‘real portraits, just not of real people’, she explains. Several pictured Dashper. In King for a Day (1991), he languishes in bed in front of his favourite boudoir painting, Diego Velázquez’s Rokeby Venus. The fabric of his model quilt is an offcut from one of his actual works.

The work in our show, Portrait of Julian Dashper (1991), finds him in his studio, making art by talking on the landline, surrounded by dollhouse versions of his works. Shannon’s Portrait is a parody of those famous shots of romantic-hero artists in their studios, as popularised by books like Alexander Liberman’s The Artist in His Studio (1960), Lord Snowden’s Private View (1965), and, closer to home, Marti Friedlander’s Contemporary New Zealand Painters A–M (1980). However, Shannon was not cutting Dashper down to size. His own project was already a parody of the heroic artist. He was a post-studio artist, but one who loved hanging out in his studio.

.

BUREN … TILLERS … DASHPER …

.

Dashper bumped into the French artist Daniel Buren at the 1979 Biennale of Sydney, European Dialogue. He would become a major reference point for Dashper.

Buren had made his big move back in the 1960s, when he stopped painting and began to produce installations instead. In these works, he used a standard pattern of alternating white and coloured vertical stripes to mark out spaces. He did this in a bewildering variety of ways. He tagged gallery walls, staircases, and other features, challenging the neutrality of gallery spaces by drawing attention to their quirks. He also worked in public spaces, pasting up striped posters, flying striped flags, and applying stripes to train doors.

Buren’s works looked abstract, but they prompted their audiences to look at relationships between the work and the world (rather than simply at relationships within the work), and thus to consider the political, cultural, economic, and aesthetic implications of their locations. Buren’s installations worked two ways. By locating his nondescript stripes in art galleries, they became art. But, once his stripe-signature was established, their appearance in other spaces prompted us to understand those spaces as art places.

Buren’s approach would become increasingly formal, mining the compositional and optical opportunities offered by his pared-back language. Buren made the three works in our show for his 1992 solo show Coloured Transparency: Situated Works at Auckland’s Sue Crockford Gallery.7 These works are portable, not site-specific, and explore formal permutations within Buren’s restricted visual language. They are, perhaps, more Walters than Dashper.

.

Australian artist Imants Tillers is a key figure for New Zealand art. He was the only overseas artist included in After McCahon in 1989. In the 1980s, Tillers put an antipodean spin on appropriation, influencing our own thinking about the provincialism problem. He argued that, especially here, on the margins, we have been exposed to international art first and foremost in reproduction, through which art works lose their scale and materiality. In response to this, he painted art images appropriated from reproductions, granting them a new sense of scale and materiality, while creating his own allegories from them. His favourite sources included international names like Giorgio de Chirico, Georg Baselitz, and Sigmar Polke, but also a fellow provincial, McCahon. Tillers repainted his images on arrays of canvasboards, making epic paintings from this modest amateur-painting medium. The canvasboards also addressed provincial isolation, allowing Tillers to pack down large paintings to send to distant exhibitions. Sometimes, Tillers exhibited the boards piled up, as sculptural stacks, as if ready to be installed or moved, their content concealed.

Tillers’s enquiry anticipates Dashper’s. Like Dashper, he was a wilful magpie, having his own way with big-name artists, taking liberties. His work also scrambled the logics of different art idioms: he was a conceptual artist who defected to painting during the heyday of neo-expressionism (or did he simply go under cover?). His work can be read through the frameworks of both painting and conceptualism, to different ends.

Tillers chose The Conquest of Space (1987) as his contribution to our show. Wystan Curnow has described this work: ‘Perhaps Tillers’ most brilliant hybrid is the Polke/Schnabel combine, overlaying a Kabuki screen pattern and Buren stripes, topped off with a grid of metallic dots’.8 The Conquest of Space is based on several sources, including Polke’s painting Scissors (1982), whose own source is a printed image of the early twentieth-century Polish medium Stanisława Tomczyk, apparently levitating a pair of scissors. So, Tillers makes a third-hand image, a reproduction of a reproduction of a reproduction (carefully reproducing Polke’s careful reproduction of the original dot-screen image). Tillers also co-opts Buren back into painting, appropriating his conceptual- art stripes for painterly effect, as a courtly-decorative feature.

The Conquest of Space is accompanied by a new stack work, Repeatable Form (1) (2015), in which a bronze reproduction of a stack of canvasboards sits on a plinth—an actual stack of canvasboards.

.

Before we went ‘digital’, artists would show dealers and curators slides of their works. How well and how much they documented their work was a measure of their seriousness and ambition. Some artists could only afford to make a few slides of each work, others made dozens, enabling them to be dispersed far and wide. Documentation was a particularly vexed matter for antipodean artists, as offshore dealers and curators would be unlikely to ever see their works in the flesh.

Dashper addressed this in a sequence of works that drew on Buren’s and Tillers’s examples. It started with a Buren steal. Dashper stretched a piece of printed striped canvas on a stretcher to make a generic, readymade ‘painting’—Untitled (1991). The work was unremarkable. However, as if anticipating excessive market and curatorial interest, Dashper made 400 unique slides of it. The trouble and expense of making and mounting the slides may have been greater than that of making the painting itself. Dashper exhibited the slides, hung in a line in twenty slide sheets, as if they were the work—Untitled (Slides 6–25) (1991). Dashper was commenting on how art circulates and is consumed in reproduction. He joked about making ‘camera-ready abstraction’.

The project’s next iteration would not be in galleries, but in art magazines. In the Summer 1991–2 issue of Art New Zealand, Dashper advertised an upcoming show.9 It would not take place in a gallery but in the advertising pages of another magazine, the January 1992 issue of Artforum. Based in New York, Artforum is the world’s most influential art magazine. Art New Zealand is something else.

In the January 1992 Artforum, Dashper’s ‘show’ took the form of a full-page ad that mimicked an Artforum cover, as if expressing Dashper’s art-star aspirations. For the image, Dashper chose a grid of stripe-painting slides. The ad, then, was a photographic reproduction of a photographic reproduction of a Buren knock off. In his ad/exhibition, Dashper changed the Artforum masthead from ‘Artforum International’ to ‘Artfrom New Zealand’, suggesting that New Zealand was excluded from the international. There’s the international Artforum art world and then there’s ‘art from New Zealand’.

In the February 1992 Artforum, Dashper followed up with a further full-page ad, this time mimicking an Artforum review page, in which Dashper’s ‘show’ in the previous issue was assessed. But the review read more like a promo-blurb.

In this string of works, Dashper fudged distinctions between work and documentation, between art and advertising, between editorial, review, and puff piece. His project extended Buren’s inquiry from primary exhibition spaces into the supplementary spaces where the real business is done.

.

CLOSER AESTHETIC RELATIONS

.

John Nixon has been a key figure in Australian art since the 1970s. A champion of the avantgarde tradition, his work draws on familiar strategies from early modernism, particularly the readymade (embracing the everyday) and reductive abstract painting (embracing the transcendental). Marcel Duchamp and Kazimir Malevich have been reference points for him. Nixon has also produced experimental music through his project Anti-Music (1979–83) and has been a key figure in the development of Australian artist-run spaces.

Dashper met Nixon in New Zealand in the 1980s, and their friendship grew after Dashper visited Sydney in 1992 for the Headlands exhibition. Their interests dovetailed and Dashper entered Nixon’s circle. His first overseas solo show was with Nixon associates, Melbourne’s Store 5, in 1993. Nixon and Dashper would show regularly with the same dealers: Sarah Cottier Gallery in Sydney, Sue Crockford Gallery in Auckland, and Hamish McKay Gallery in Wellington. They made collaborative works, juxtaposing signature elements from their respective oeuvres (for instance, Dashper target drumheads with Nixon orange monochromes). They also released records on their label, Circle Records. Dashper would be highly influenced by Nixon’s physically and conceptually streamlined approach to exhibition making. Like Nixon, he would increasingly exhibit far and wide, making portable shows he could carry in a suitcase or create in situ.

In 2005, Auckland’s Gus Fisher Gallery presented Julian Dashper / John Nixon: The World Is Your Studio, a show addressing Nixon’s and Dashper’s artistic conversation. As a centrepiece, curator Ben Curnow juxtaposed Nixon’s installation Blue Rider (1994) and Dashper’s Untitled (The Warriors) (1998). This pairing is repeated in our show.

In Nixon’s installation, four red monochrome panels rest on a grand piano. The piano epitomises the bourgeois classical-music tradition, but also suggests fluxus artists, like Joseph Beuys, who used it to attack that tradition. Via Malevich, the red monochromes recall the Russian Revolution. The work’s title refers to a band of German expressionists, operating from 1911 to 1914, who gathered around Wassily Kandinsky, another Russian pioneer of abstraction. Blue Rider, then, is a mix of contradictory references—to iconolation and iconoclasm, to tradition and revolution (artistic and political)—held in tension.

The Warriors also holds ideas in check. In this work, Dashper fitted his signature target drumheads to a downscaled child’s drum kit. His title also refers to a collective, to the only New Zealand team playing in the Australian National Rugby League.10 The Warriors has been read as symbolising New Zealand’s little-brother relationship to Australia. But, like the Warriors, if New Zealand artists are in competition with Australian artists, at least they are now in the same league. The juxtaposition of Blue Rider and The Warriors declares the artists’ differences as much as their allegiances. Nixon’s work is serious, portentous, and melancholic; Dashper’s comic and pop—a Happy Meal.

.

INANE ANECDOTES

.

Dashper revelled in art-world legends. He was forever spinning yarns himself, as artist statements and in talks. For this, Andy Warhol and Julian Schnabel were among his models. Warhol’s autobiography, a, A Novel (1968), was a rambling unedited transcript of taped conversations, while Schnabel’s autobiography, C.V.J: Nicknames of the Maitre D’s and Other Excerpts from Life (1987), included such valuable insights as ‘In New York, my plan was to eat pizza and paint pictures.’

Dashper’s tales expressed a similar faux naivety. One Dashper exhibition statement included an account of John Nixon purchasing ill-fitting secondhand Levi’s in New York. Nixon tried to offload them onto fellow Sydney artist A.D.S. Donaldson, but they didn’t fit him either. Eventually, Dashper took them, but they got irreparably stained in the rear when Dashper sat on a rusty bollard outside Matthew Marks Gallery in New York.11 Relevance? Is there some unconscious subtext to this suggestive tale of artists in one another’s pants, rusty bollards, and stains? Is it a would-be Cinderella story, in which the New York glass slipper is a pair of jeans—an allegory about antipodean artists’ fantasy relationship to the Big Apple? Or, is simply it a digression into real-life randomness? Dashper left the question hanging.

Marie Shannon joined in on the fun. Several of her photos reproduced texts purporting to recount Dashper’s dreams. In one, Dick Frizzell’s Retrospective (1994), Frizzell scores a retrospective in Fiji and pronounces his name ‘Frizzle’. In Julian’s Dream, Julian’s Nightmare (1995), a gallery goer, joining the crowd avoiding Dashper’s bizarre contribution, accidentally spills their Dutch Fristi drink onto an esteemed terracotta-and-blue Mrkuisch painting in a neighbouring space (the dream), and Shannon similarly spills mustard on Dashper’s Christian Dior shirt, which she happens to be wearing (the nightmare).

Dreams have an ambiguous status. On the one hand, we don’t feel responsible for them (it’s our unconscious); on the other, we do (it’s our unconscious). Tinged by both schadenfreude and resentment, Shannon’s tales could have been dreamed by Dashper and recounted by Shannon, but, equally, they could also have been made up by her and attributed to him (and his unconscious). We can’t tell whose unconscious (or consciousness) is at work here.

.

CIRCLES AND LINKS

.

The circle is a modernist trope, one particularly associated with the constructivist tradition of abstraction. The constructivist-art bible of 1937 was called Circle. In the late 1980s, Dashper drew circles in his paintings to acknowledge this international tradition, and, closer to home, its local exponents Mrkusich and Walters. But, Dashper was never exactly an abstract artist. Even his most rarefied abstractions point beyond themselves, into the everyday world. Take Phili Shave Red (1989). Its title prompts us to think of its circles as the heads of an electric shaver.

Dashper endlessly played on formal and conceptual relationships between circles, targets, Os, and frames; between frames and chain links; between records and drumheads. A series of untitled paintings from 1990–2, nicknamed ‘the bagels’, reproduce, in different colours, the Futura Extra Black letter O from the Ilford trademark. This O is almost a circle. Dashper also made works based on the condensed O from the Artforum masthead. Exploring semantics, he reproduced that O as a screenprint on a canvasboard and as a photograph. The screenprint was unframed, the photo framed and glazed (the frame reiterating the shape of the O).

Dashper also made records—which are, of course, circular—on his label Circle Records. Some were of experimental-music jams, others were field recordings (for instance, some made in front of Jackson Pollock’s Blue Poles at Canberra’s National Gallery of Australia). He displayed the records, silently, as art objects; in their sleeves, or out of them. The idea was typically more important than how it sounded.

Like records, drumheads can make sounds, but not when treated as paintings and hung on a wall. When Dashper painted targets on drumheads, he superimposed one circle idea on another.

Dashper also played on the relation between frames and chain links. In Chain Frame (1992), he linked two empty gold frames, like a magician’s linking rings. Did this suggest the intersection of their contents (like a Venn diagram) or their inability to contain anything? He also made works using lengths of store-bought plastic chain, whose links, incidentally, recalled the Artforum O. Sometimes he hung works from them, sometimes left them dangling.

Circles, Os, and frames don’t have to be physically linked to form chains of association …

.

Dashper’s interest in frames and chains links him with Australian artist Peter Tyndall. Tyndall’s works have evolved out of his symbol for the art work: a rectangle (suggesting a frame) with two lines extending from it (suggesting the strings from which it hangs). This symbol deftly conveys the insight that an artwork is, at once, a thing apart from the world (framed off from it) and connected to it (strings attached). The work—any thing or ‘detail’, in fact—is at once independent and interdependent. In elaborating on this deceptively simple idea, Tyndall has engineered a complex body of work. In it, his frame signs are frequently organised in algebraic equations or collude as chains and networks. Sometimes, these signs escape the diagram and enter into the real world to interact with it. Tyndall’s work is a parody of analysis. His madness-in-his-method mantra: ‘LOGOS/HA HA’.

.

Peter Robinson recalled Dashper’s O-and-chain imagery with his 2001 Venice Biennale project Divine Comedy. It addressed themes of nihilism and nothingness via bookish references to Dante, existentialism, Stephen Hawking, and stealth technology. In this project, the O was not a letter but a number—zero. Divine Comedy included Null and Void (2001), a sleek minimalist sculpture consisting of a hefty stack of identical, large, red-lacquered MDF ovals. Their shape was the negative space inside the Gill Sans zero. Robinson materialised the absence in the heart of nothing. In our show is another work from Divine Comedy, Zero Red Shift (2000), a chain whose plastic links are zeroes cut in every typeface available on Robinson’s computer—different faces of nothing.12

.

READYMADE ABSTRACTION

.

Dashper did not see abstraction as something apart, but as a part of the world. He said that he approached abstraction as a ‘readymade’, sourcing it both in the everyday world and in the world of art. By the time Dashper became an artist, abstraction was not revolutionary, but a well-mapped tradition, one he could work within and freely quote from. His work was less about formal invention (boldly going where no man has gone before), more about working an already busy room. It was convivial.

In 1992, Dutch artist Jan van der Ploeg visited New Zealand to present his work as part of a project marking Abel Tasman Year, the 350th anniversary of Abel Tasman discovering New Zealand.13 He and Dashper became pals. In 1993, they had a two-person show at Leiden’s Stelling Gallery, and, in 1994, Dashper organised a residency in Auckland for Van der Ploeg. Over the years, they often showed together. Van der Ploeg was a co-founder and director of PS Projectspace, an Amsterdam exhibition space that showcases new abstract and conceptual art. Dashper became part of the stable, having solo shows there in 1999, 2002, 2005, 2007, and 2008. And, in 2013, Van der Ploeg curated a show there, pairing Dashper with American minimalist star Donald Judd.

Van der Ploeg is known for his architecturally scaled murals. With their simple hard-edged geometries and bold colours, they echo the art languages of minimalism and pop (Sol LeWitt and Ellsworth Kelly) and design aesthetics (supergraphics). He also produces smaller works on canvas featuring the same geometric elements. Van der Ploeg often bases his abstractions on real-world things. Since 1997, he has been exploring his ‘grip’ motif—a long, horizontal rectangle with rounded corners, based on the hand holes in cardboard removals boxes. For our show, he’s produced a new wall painting in this series.

.

PERIPHERAL VISION

.

Barrie Bates escaped New Zealand in 1959. He left to study at London’s Royal College of Art, where he became part of a new generation of British pop artists. In 1962, he reinvented himself as Billy Apple and used his work to promote this new art brand. In 1964, he moved to New York, and, in 1969, he established Apple, one of the city’s first alternative spaces. There, he would produce increasingly conceptual and process-based works. His work became a unique blend of pop and conceptualism.

Apple returned to New Zealand twice in the 1970s, invited by the QEII Arts Council, who were keen that the local scene play catch-up with international developments. On these visits, Apple came to represent everything mainstream New Zealand art was not. Both times, he presented a series of shows in spaces throughout the country. On the second visit, in 1979–80, his shows, subtitled The Given as an Art-Political Statement, addressed the physical properties of galleries as symptoms of art- world politics, exposing the relationships between galleries, artists, and audiences. In the installations, Apple identified problems with gallery spaces and proposed or made improvements. His shows surprised audiences, because they addressed elements of art that seemed to be outside the scope of art and the art discussion.

In our show, Apple is represented by two works produced following his Exposé show at Wellington’s National Art Gallery in 1979. For Exposé, Apple decided to retire two large paintings by British painter Sir Frank Brangwyn that had been permanently installed in the foyer. In the process, he discovered that they had been screwed to the walls through the canvases and their stretchers. Only one screw came out whole; the others had their heads drilled out, leaving the shanks stuck in the wall when the paintings were demounted. A poster explained what Apple had done. Exposé began with the thought of questioning the dominant positioning of the Brangwyns, but became a critique of their mistreatment by the national institution.

In one of the Exposé-related works in our show, Apple framed two of his posters and attached a shard of the wooden batten that concealed the screws and the single screw he managed to extract. The work was a kind of reliquary, with the screw and shard suggesting a nail and splinter from The Cross.

If Exposé dealt with the institution’s mistreatment of the murals, the second work documented Apple’s own mistreatment at their hands. Although the original concept was his, Apple hated the Exposé poster. He wanted it to conform to the look of the other posters he produced for the 1979–80 tour, with his signature typography. However, the National Art Gallery’s designer had his own ideas, changing Apple’s layout, typeface, palette, and paper stock—everything, really. In the work, Apple juxtaposed his original design rough and the end result, marked up with corrections, pointing out every error and deviation. Bad Gallery!

Dashper was influenced by Apple’s treating the artist as a brand and by Apple’s fascination with overlooked art-world supplements (everything that was not the art that the art depended on). Apple placed such supplements centre stage—for instance, the gallery became the art, or the poster became the art. Similarly, Dashper produced quirky ads, letterhead, and business cards. He framed promotional materials as art and addressed gallery spaces. He made catalogues for many shows, at a time when this was unusual, co-opting the critics. Apple’s The Given as an Art-Political Statement was a model for Dashper’s project, The Big Bang Theory, which also took the form of a national tour. Our show includes the official photo documenting the installation of Dashper’s The Colin McCahons in the Auckland Art Gallery auditorium in 1992.

.

Dashper taught Dane Mitchell. Like Dashper and Apple, Mitchell went behind the scenes, exploring the operations of galleries, public and private. He framed his works as museum-studies research. He loved catching gallery directors doing their jobs with undue zeal. He cut records of his phone calls with Auckland Art Gallery’s Chris Saines (where Saines defended his staff) and me at Artspace (where I screeched, demanding the return of my sandwich board). He later invited in the public to mix the recordings at a DJ booth.14 In 2000, he exhibited the tell-tale contents of Auckland dealer gallery Gow Langsford’s rubbish bin, offering insights into the Gallery’s operations and culture. When the Gallery’s lawyers petitioned him to cease-and-desist, he exhibited their letter with his legal reply. From 2003 on, Mitchell sampled dust and bacteria from various galleries, grew it in Petri dishes, and sent it to the lab for analysis, as if seeking to diagnose art-world ills.

In our show, Mitchell is represented by Collateral, the work that won him the 2009 Trust Waikato National Contemporary Art Award, at Hamilton’s Waikato Museum. His work was a pile of rubbish. Mitchell asked that discarded wrapping materials from other entries be gathered and presented as his own work. Judge Charlotte Huddleston, Te Papa’s Curator of Contemporary Art, annoyed other entrants by giving Mitchell the prize, belittling their craft (and craft in general) by implying that their works were somehow less than the wrapping they came in.15 (In a sense, Huddleston co-authored the work by picking it, because Mitchell’s gesture would have meant little if it hadn’t won.) It was another case of ‘the given as an art-political statement’.

.

Fiona Connor first became known for making works that replicated peripheral elements of gallery architecture: Artspace’s staircase, Michael Lett’s facade, and the New Gallery’s ceiling bracing. Like Apple with his ‘givens’, she went for features that normally go unseen and unmentioned. While Apple drew attention to givens by removing or highlighting them, Connor did so by mimicking them, fastidiously. Where Apple was politically motivated, addressing politically loaded features, Connor was less pointed, less judgemental. Indeed, it wasn’t clear why she picked the things she did. She created Working Title (2006), a replica of Artspace’s glass door, for Artspace’s 2006 new-artists show, Headway. It became an uncanny double. In placing it near the actual door, Connor made people look twice, drawing attention both to the door’s properties and to her powers of mimesis. ‘I like the idea of making works about difference where there is not that much difference’, she said.16 Connor went on to explore other kinds of peripheral phenomena, beyond art galleries.

.

Like Apple, Dashper often addressed the not-art part of art. Our show includes Julian Dashper at No. 5 (1992), the absurdly grand, even triumphal, promotional banner he created for his solo show at the humble No. 5 Gallery in remote Dunedin. It was the kind of point-of-sale device one would expect to see outside a major metropolitan museum doing a blockbuster show of a star artist. But Dashper was still a young buck and had only just given up his taxi-driving day job. A routine show became an alibi to indulge in extreme marketing, implying he had the product to match. It was all about the bling.

.

EMPTY CHAIRS

.

In 1993, Dashper presented his installation What I Am Reading at the Moment at Wellington’s National Library Gallery. A stack of Artforum magazines was accompanied by an old armchair that had seen better days. The chair had form. Before Dashper acquired it for his studio, it appeared in the iconic Art New Zealand cover photograph of the cast of the 1982 exhibition Seven Painters/The Eighties.16 That show turned out to be a belated New Zealand attempt to promote abstraction as the great leap forward, neo-expressionism being almost upon us. In Ian Macdonald’s photo, the only expat, the one actually living in New York, Max Gimblett, sits in the chair, with the locals grouped around him. (In fact, during the shoot, others had a go in the seat, but the magazine preferred a Gimblett-centric view.) Dashper’s work, then, represents his provincial situation, sitting on a discarded, dilapidated throne, inherited from an older generation of antipodean internationalists, still working his way through back issues of Artforum. Or, is he inviting us to sit there?

.

The title of Marie Shannon’s video What I Am Looking At (2011) pointedly recalls that of Dashper’s installation. It is also about empty chairs. She made it after Dashper died, while wondering what to do with the contents of his studio. We hear her describe the studio’s contents, listing objects—precious, mundane, and baffling—as she considers the work required to make sense of all this, in the artist’s absence, without his advice on what counts. She makes decisions, she changes her mind. While her account is matter-of-fact, this only emphasises how emotional the experience must have been for Shannon. As we listen to her, her words scroll up the black screen. The work of the dead has become the work of the living.

.

NEVER CYNICAL

.

In 1992, my essay for the Headlands catalogue described Dashper as a ‘postmodern cynic’.18 It was early days and I meant no offence. Indeed, at the time, I thought being a postmodern cynic was a good thing. But, Dashper considered it a slight—he took it to heart. While he was part of the postmodern turn, it was important for Dashper to be seen as a believer.

Dashper was romantic about the art world and the art business. If he preyed on the legends and reputations of famous artists, it was because he would have liked to join them in the canon. When he cast his spotlight on the art world’s supplementary devices and supports, it was not to engage in institutional critique but in fetishistic delight. He didn’t want to stop the machine but to polish it and to enjoy his reflection in it. Dashper’s love of art and the art world was a provincial thing. His desire to be included was honed by a sense of being excluded, as a New Zealand artist.

Dashper’s project was about the adventure of being an artist, whether it was working away in his studio or being on the road, making shows. In the discursive space of art, his works were in dialogue with those of other artists, and, in the real world, he was in face-to-face conversations with the actual artists whose paths he crossed and shared. Dashper was, at once, one of our most influenced artists and one of our most influential artists. Friendship wasn’t incidental to his project, it was his medium.

The conversation continues.

.

[IMAGE: Julian Dashper The Colin McCahons 1992]

- Francis Pound, ‘Deathdate’, Water Color (Auckland: Julian Dashper, 1991), np.

- Motorway Schools, 100m2, Auckland, 1980.

- Colin McCahon: A Survey Exhibition (Auckland: Auckland City Art Gallery, 1972), 28.

- www.aucklandartgallery.com/the-collection/browse-artwork/13863/ ad-1968.

- Francis Pound, ‘In the Wake of McCahon: A Commentary on After McCahon’, Art New Zealand, no. 52, Spring 1989: 82.

- Francis Pound, ‘Walters and the Canon’, in Gordon Walters: Order and Intuition (Auckland: Walters Publication, 1989), 61.

- Buren was no stranger to New Zealand. In 1990, he filled Wellington’s Shed 11 with his installation Kei te Anganui/At the Opposite. He returned in 1992, for his Crockford show. He also produced an outdoor installation, Green and White Fence (1999– 2001), for Alan Gibbs’s farm in the Kaipara.

- Wystan Curnow, Imants Tillers and the ‘Book of Power’ (Sydney: Craftsman House, 1998), 90.

- No. 61, Summer 1991–2.

- Dashper was a huge Warriors fan. Warriors hard man Ruben Wiki visited him during his final illness.

- Dashper was offering the backstory to his work Untitled (After Nixon, Donaldson, and Pistoletto) (1995–), included in his 1998 solo exhibition at Hamish McKay Gallery, Wellington. ‘Artist’s Statement’, This Is not Writing (Auckland: Clouds and Michael Lett, 2010), 79.

- Later, Robinson returned to the chain idea, creating installations using white polystyrene chains with links of different scales, from tiddly to massive—different scales of nothingness. For instance, Snow Ball Blind Time, at New Plymouth’s Govett-Brewster Art Gallery in 2008.

- The visit was a speaking tour; there was no gallery exhibition. Van der Ploeg spoke about his work in public galleries and art schools in Auckland, Wellington, New Plymouth, Christchurch, and Whanganui.

- For the group show, Only the Lonely, Artspace, Auckland, 1999.

- ‘Other local artists Collette Fergus and Bruce McLachlan said nthe winning entry was “the worst yet”. “A pile of rubbish that wasn’t even created by this guy is worth $15,000?”, Fergus asked. She said it was a “sad mockery of us all and an embarrassment to the arts community”.’ ‘Losers Complain about Winning “Rubbish” Artwork’, www.3news.co.nz/entertainment/losers-complain-about-winning-rubbish-artwork-2009090814#axzz3qwKKpiAR.

- www.thearts.co.nz/artists/fiona-connor.

- No. 28, Spring 1983.

- ‘Mod Cons’, Headlands: Thinking through New Zealand Art (Sydney: Museum of Contemporary Art, 1992), 167.