Unpublished.

Patrick Pound has turned a collecting pastime into an art career. The Melbourne artist gathers examples of this and that, framing his resulting collections as authored art works. Among other things, he’s made a Gallery of Air and a Museum of Holes. By bringing things together, he alerts us to similarities and differences. Once accumulated, his examples march to a new beat—theme and variations. Pound’s collecting focuses on vernacular photos. One project gathers photos of people on phones. The ensemble includes film stills and celebrity head shots, snapshots, product shots, and a wire-service image. Most are film stills, perhaps asking us to wonder why these should figure so prominently.

The collection was shown in Pound’s 2018 solo show, On Reflection, at City Gallery Wellington. Pound constructed the show as a palindrome, with different collections mirroring one another across the space. The phone pictures were divided by gender. On one side of the space, on one wall, Pound clustered photos of women on the phone. On the corresponding wall, on the other side, it was men. The same (phones), but different (gender). This prompted visitors to think of the wings of the show as being ‘in conversation’ with one another.

Looking at the photos together, we first identify the common thread—‘spot the phone’. Then, there’s the pleasure of recognising familiar faces (movie stars and other celebrities) and familiar films. A different kind of enjoyment comes from the images that are obscure, bewildering, inexplicable, surreal. We scan and map the collection, playing compare-and-contrast, finding commonalities and deviations, themes and vectors. Images conspire. There are men, women, couples; people talking, people listening; facts and fictions; different eras and film genres (sit-com, rom-com, thriller, noir). Some images are serious, some laughable. Here’s a clean phone; there’s a dirty one. In many of the film stills, the phones are incidental; in others—for When a Stranger Calls, Pillow Talk, Dial M for Murder, Butterfield 8, Play Misty for Me, and Sleepless in Seattle—they are central to the films’ plots and brands (these films are about phones). There are also jokes. A still of Nancy Allen in Dressed to Kill identifies her as a ‘call girl’.

Pinned up in clusters on painted-black walls in the show, Pound’s phone pictures recalled Aby Warburg’s Mnemosyne Atlas. Long before Pinterest, the quirky German art-historian-cum-detective clustered photos of art works and other things drawn from across cultures and times on black pinboards, as if on the verge of explaining culture’s unsolved mysteries. Pound’s project isn’t so serious—it’s Warburg lite, Warburg for dummies. But, like the Atlas, his collected phone pictures make us wonder how much significance lies in the images themselves and how much in what we bring to them, our propensity to join dots, to put one and one together.

The photos are all dated—retro, obsolete. Whether made to spruik films, to document loved ones, or whatever, they’ve outlived their original purpose. Cut loose, they’re become refugees, which is why they’re now available to Pound. The phones in the photos are similarly dated—all landlines. Several may be cordless, but there are no cellphones. The photos come from a time when phones were necessarily grounded—when you ‘placed’ a call, less to someone else than to somewhere else. The still of Carol Kane in When a Stranger Calls plays on this, in being exceptional. That film’s terrific twist is discovering that the killer is calling not from another place but, inconceivably, from the self same place, feigning distance.

In On Reflection, Pound split the collection to emphasise gender difference. In those old film stills, men are manly, women womanly; men acting like men, women like women. Men on the phone mostly suggest agency, while women are more likely to suggest emotion—even pathos. Among the stills, there’s a distressed Anne Bancroft on a bed, a phone headset dangling by her—a still from The Slender Thread. It reminds me of iconic tragic woman-on-phone art photos: Cindy Sherman’s ‘centrefold’ Untitled #90 (1981)—a woman lying on a couch, staring at a phone, waiting for it to ring; and Darren Sylvester’s Just Death Is True (2006)—another recumbent woman, in a blue face pack, on the phone, staring vacantly, affectless. Fill in your own sexist scenario.

Film stills are odd. They’re representations that refer to other representations, still images that imply moving ones. They tease, making us curious about the films they refer to. In films, when two characters talk on the phone, we typically cut between them in their locales—shot, reverse shot. Phone-call scenes often turn on the fact that the callers can only hear one another, while we can see them too—we’re party to visual information they lack. But, in a film still, we hear nothing and only see half the exchange—we’re in the dark. We can’t see if the receiver is wearing ‘something more comfortable’ or a shoulder holster. We are left to wonder, based on what we can see.

Of course, with film stills, it’s safe to assume that the phones were only ever props, never connected, and that the conversations were contrived on an editing desk. Just as a filmmaker splices shots to create the illusion of a conversation, with Pound’s phone photos we do this in our heads. The big conceit here is that people-on-the-phone photos are intrinsically incomplete, half a story. They imply other people we can’t see (or hear) beyond the frame, on the other end of the call.

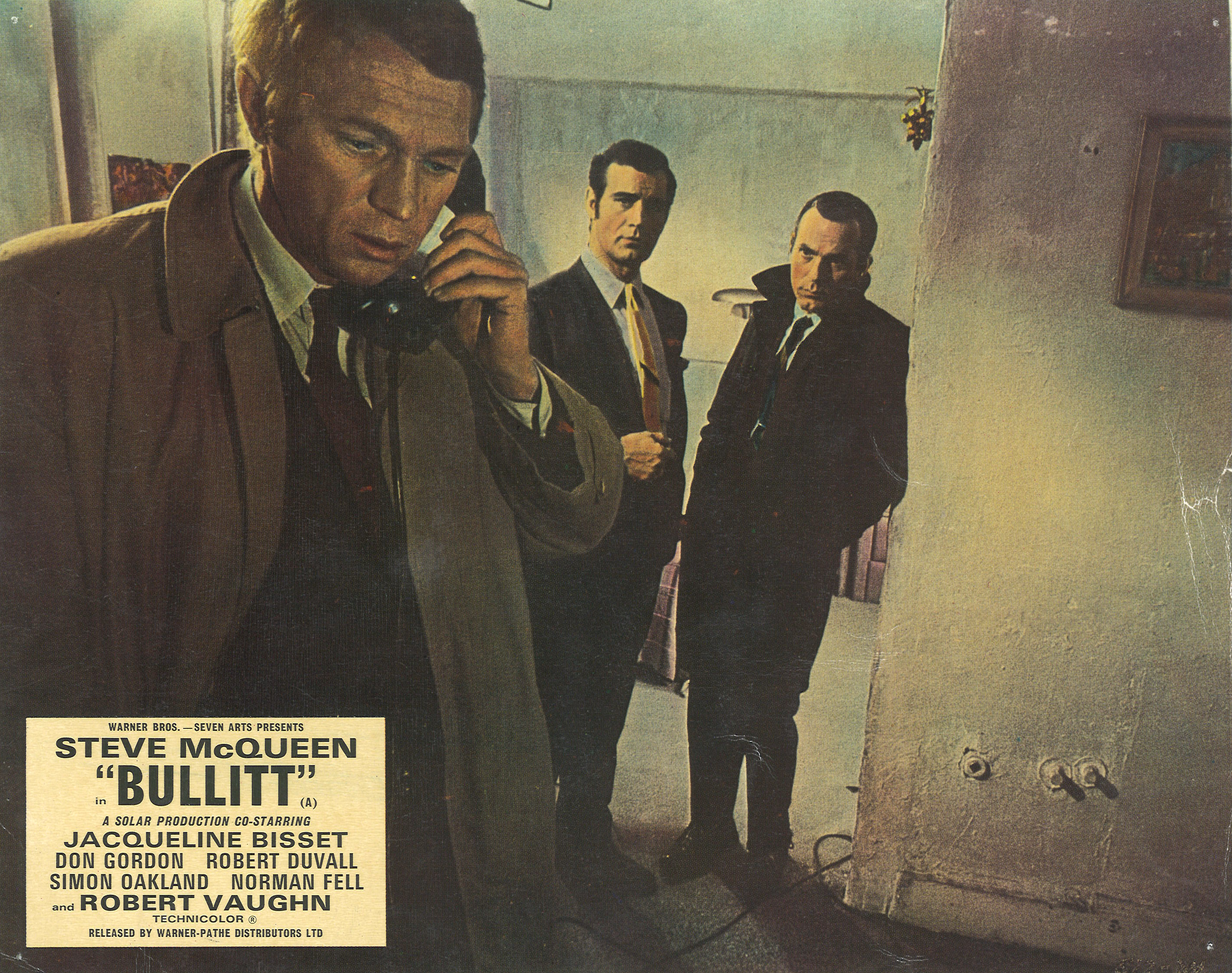

So, with Pound’s collection, we instinctively pair up images as possible conversations as if in a game of exquisite corpse, making the collection one big telephone exchange. The collection suggests endless absurd plot mashups; with someone placing a call, and someone else in another time and perhaps another film genre picking up. Is Hunter S. Thompson (in real life) appealing to Leslie Caron (in the The Man Who Understood Women)? Has Eva Marie Saint (exiting the phone booth in North by Northwest) left Catherine Deneuve (in Repulsion) hanging. Perhaps Steve McQueen (in Bullitt) is calling Betty Rubble (on her shellphone). Perhaps a maudlin Woody Allen in a phone booth in the rain (in 1986’s Hannah and her Sisters) is checking in with a fraught younger Mia Farrow (in 1968’s Rosemary’s Baby). Famous fictional somebodies from films could be calling blurry-snapshot real-world non-entities.

Endless faulty connections, wrong numbers, and phone pranks are suggested. However, two images clearly do dovetail. Pound includes separate shots of Sidney Poitier and of Bancroft from The Slender Thread, who would conceivably be on the phone to one another. That film’s title refers to the phone as lifeline. The funniest inclusion is Henry Kissinger on the phone. How could he be implicated in these scenarios? Perhaps he’s tormenting Carol Kane in When a Stranger Calls. Imagine his gravelly voice asking: ‘Have you checked ze children?’

The telephone exchange is a metaphor for Pound’s wider project. When you gather things in a collection, they seem to talk to one another.