.

In recent years, Wellington’s Adam Art Gallery has distinguished itself by presenting related shows in counterpoint, in compelling constellations. This has proved a brilliant solution to the constraints of their tiny budget and idiosyncratic spaces. The current mix of shows is smart. Director Tina Barton must be pleased.

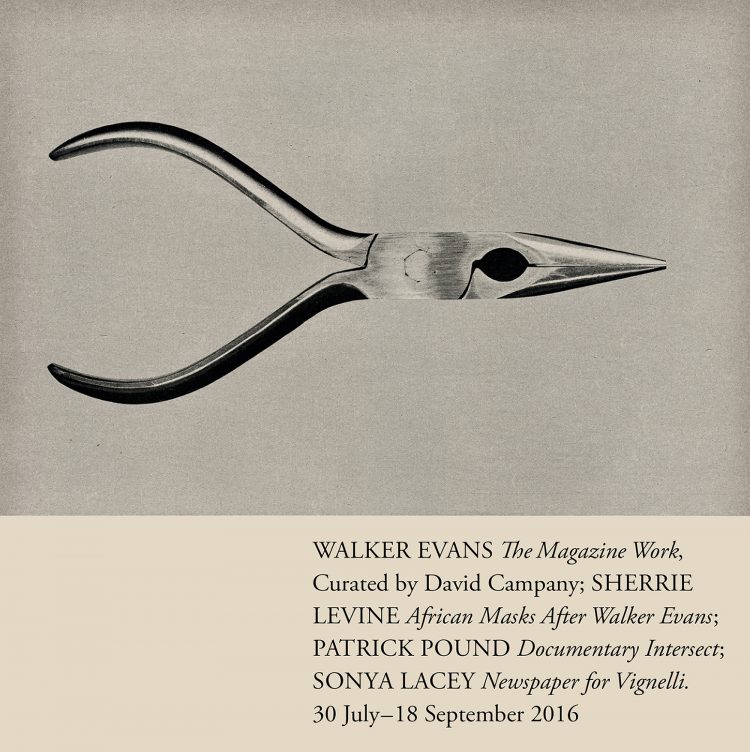

The anchor show, Walker Evans: The Magazine Work, has been touring for several years and was clearly a labour of love for British photography curator David Campany. Evans is a canonical figure in American photography, whose career ran from the 1920s to the 1970s. His key images have become icons of art photography and American social history. However, here Campany has approached Evans obliquely, showcasing not these iconic images but the less-known photo-essays he produced for magazines, which often offered a quirky commentary on American life. In assembling his show, Campany rejected the idea of including original prints, preferring to display the actual magazines, which he personally acquired—thanks eBay. Alongside them, he stuck blow-ups of the magazine pages to the gallery walls. Campany’s presentation links and contrasts the logics of the magazine and the exhibition, while cross-referencing his collecting, sorting, and arranging (as curator) with Evans’s (as photographer and artist).

Alongside this main dish, the Adam added three tasting plates: American artist Sherrie Levine’s recent series, African Masks after Walker Evans; New Zealand-born, Melbourne-based Patrick Pound’s project, Documentary Intersect; and local artist Sonya Lacey’s film, Newspaper for Vignelli. Their proximity to the Evans show opens it up in numerous ways.

Levine is synonymous with the idea of appropriation. In 1979, she famously re-produced classic Evans photos of the American South made during the Depression, as if asking: What does it mean for me—as a woman, now—to reiterate these iconic masterpieces? With such gestures, Levine became the art-theory pizza with everything: ‘a feminist hijacking of patriarchal authority, a critique of the commodification of art, and an elegy on the death of modernism’. In 2014, she returned to Evans, reproducing twenty-four photos of African masks from the hundreds he had made in 1935 to document the Museum of Modern Art show African Negro Art. Unlike those images of the South (made around the same time), the Masks are not popularly associated with Evans and seem out of place in his oeuvre. Evans did not make them as (his) art, but as a pay job—of course, one might claim this of his magazine works too. In 2000, his Masks were unearthed in Perfect Documents: Walker Evans and African Art 1935 at the Metropolitan Museum, New York. In 2012, they reappeared in Intense Proximity, the Paris Triennale, curated by Okwui Enwezor, where they kept company with other ethnographic-documents-turned-art, including Claude Lévi-Strauss drawings and a Jean Rouch film. With its Primitivism show in 1984, MOMA was roundly condemned for its bad habit of appropriating primitive art to provide a legitimising context for modernism. By including Evans’s photos in his show, Enwezor located the unwitting photographer within that dodgy history, granting him an authorial role he may well have shrugged. In appropriating the same images in 2014, Levine added a twist, putting all that history into conversation with her earlier appropriations of ‘signature’ Evans images.

Who knows what Evans would have thought of this (or, indeed, of Campany’s treatment of his magazine works)? Of course, it’s irrelevant. Evans’s images have entered the culture and curators and other artists will make of them what they will, reinventing Evans.

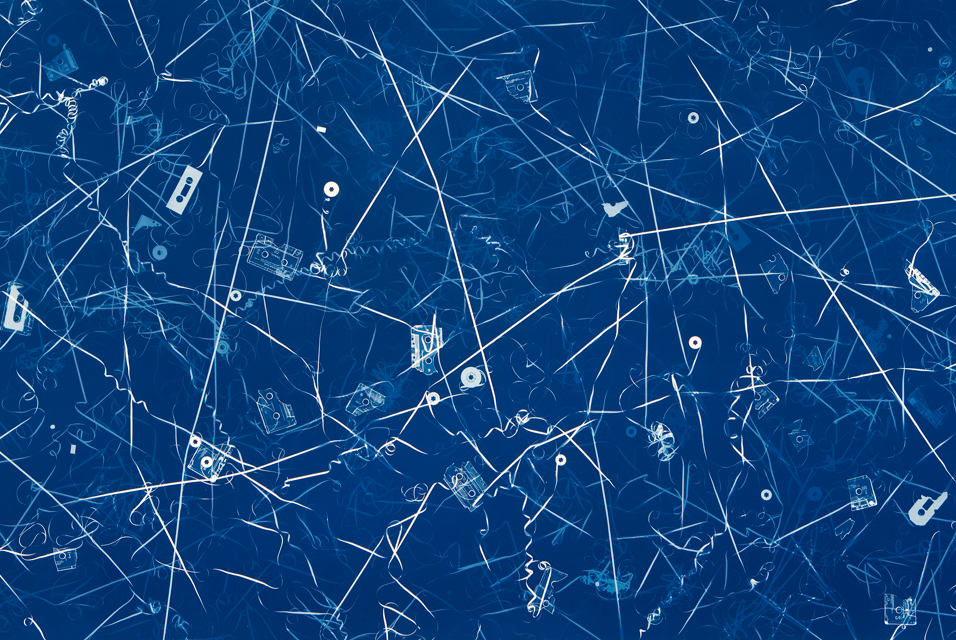

Campany is a curator and an artist. His projects often fudge the distinction. So do Patrick Pound’s. Pound makes exhibitions from collections, particularly his own collections. Documentary Intersect links his personal holdings of photos of ‘tears’, ‘floral clocks’, ‘crime scenes’, ‘sleepers’, and San Francisco’s Cliff House. Blu-tacked to the wall in horizontal and vertical lines by category, intersecting on common images, they are like a pictorial crossword. Pound plays on the way images are framed off from one another, yet in dialogue. His mind map intersects with Evans, one of whose photo-essays reproduced a postcard of Cliff House from his own collection (Pound tracked down and included a copy of the very same card). While Pound speaks to this arcane detail within Campany’s Evans project, it also speaks to Evans’s and Campany’s enterprises in general—to Evans’s postcard collecting and to Campany, following him, tracking down all those magazines, joining dots, putting twos and twos together. Foregrounding the collectors-curators’ mindset (or pathology), Pound suggests that they are akin to photographers, as taking photos is essentially a form of collecting—of curating—the world. Of course, this is also a conceit, drawing attention to the Adam’s own curatorial gambit, in forming this precise cluster of shows. Curating about curating.

In her retro-looking black-and-white 16mm film Newspaper for Vignelli, Sonya Lacey chases newspaper pages as they are blown across the ground by the wind, like mass-media tumbleweeds. (It reminds me of that poignant scene in American Beauty, where, in a courtship ritual, a boy and girl watch a video of a plastic bag magically dancing, buffeted by air currents.) But the film is not as casual as it looks and it is not just any newspaper—it is way more contrived. Lacey created the newspaper in question, basing it on Massimo Vignelli’s proposed but unimplemented modernist design for the European Journal of 1978. I’m prompted to read her melancholy film as a key to the Adam’s current ensemble of shows, in which various originals and reiterations find themselves caught up in winds of change, propelled by history, with the Gallery and we viewers, like Lacey, in hot pursuit. The answer, my friend, is blowing in the wind. (Adam Art Gallery, until 18 September).