.

Above: Wellington’s proposed film museum and conference centre. Below: The Broad, LA, designed by Diller Scofidio + Renfro.

•

Mrkusich Cornered

..

When the abstract painter Milan Mrkusich died last month, at the ripe old age of ninety-three, it felt like the end of an era. The ‘big three’ of the New Zealand national-art canon—Rita Angus, Colin McCahon, and Toss Woollaston—were long gone, passing in 1970, 1987, and 1998 respectively; and Gordon Walters, Mrkusich’s fellow traveller in modernist abstraction, departed in 1995. So Mrkusich outlived them all—by almost twenty years.

In New Zealand, Mrkusich has always been the textbook exemplar of modernist abstraction—modernist abstraction and nothing but. He started working in an abstract idiom in the mid-1940s. From the outset, his work was rooted in design principles—the Bauhaus. He did modernist interior and furniture design as a day job. Then, in 1952, he built himself an award-winning modernist home, where he would live and work for the remainder of his days in splendid isolation. (Marti Friedlander’s photos of him there—in his clean, orderly studio—implied that his art and life were of a piece.)

In the 1950s and 1960s, Mrkusich worked his way through a range of art idioms and ideas. In different works, we hear echoes of Piet Mondrian, John Tunnard, Ben Nicholson, Mark Rothko, etcetera. At this time, McCahon was also considering his options, trying stuff out. While Mrkusich and McCahon would later seem to be poles apart, their works in these years sometimes seem to be caught in a dialogue, a dance. At Auckland Art Gallery, I always loved seeing Mrkusich’s cubisty City Lights (1955) hanging alongside McCahon’s cubisty Flounder Fishing, Night, French Bay (1957) in a game of visual Snap.

In the 1960s, Mrkusich’s paintings sometimes emphasised designy graphic and geometric elements, sometimes expressive painterly ones, and sometimes combined them, as if seeking some resolution between thought and feeling, calculation and intuition. My favourite example: Painting 62–19 (Little Radiance) (1962). His Emblems (1963) and Elements (1965) fused formal inquiry with metaphysical symbolism, lifted from Rudolf Koch’s The Book of Signs.

Mrkusich’s breakthrough came in 1968, when he began his radically simple Corner paintings. They were more-or-less monochrome fields—some flat as, some inflected and ‘atmospheric’. They had contrastingly hued and toned triangular ‘corners’. Resembling photo corners or blotter corners, they seemed to hold the colour fields in place and more-and-less impeded our gazes from escaping the field. In some examples, the corners were the same hue and tone; in others, the corners optically advanced and receded to different extents, torquing the fields. The best are about sixty-eight inches square—neither big nor small, dominant nor submissive. The Corner paintings were the ultimate resolution of material literalness and immaterial beyondness, the architectural and the atmospheric, without resorting to symbolism or allegory.

With the Corner paintings, Mrkusich nailed it. It was hard to see how or where the idea could be taken further. And, in a larger scene, perhaps he could have gone on making them forever. In subsequent decades, Mrkusich continued to make important, handsome works, but nothing to top the brilliance and consequence of the Corner paintings—or build on them.

It’s often said that in New Zealand abstraction was neglected—marginalised. There’s truth to this. But Mrkusich was also hugely successful. He had his Auckland City Art Gallery retrospective at in 1972, the same year as McCahon. In the 1970s, Mrkusich first, then Walters, were the big-name abstract painters. They were cornerstones in the argument of Auckland’s legendary separatist Petar/James Gallery, which championed formal abstraction and also represented young-turk painters, including Stephen Bambury, Richard Killeen, and Ian Scott.

Nothing holds. In the late 1980s, the battle lines would shift again, with postmodernism. Abstraction would be read in a new way, a ‘post-formalist’ way—less as form, more as sign. As if in response, Mrkusich softened his formalist hard line, allowing allusions to landscape and metaphysics to return in his Journeys (1986–9), Chinese Elements (1989), and Alchemical Spectrum (1990). Later, he would duet with younger post-formalist abstract artists, like John Nixon (at Sue Crockford Gallery, Auckland, in 2007) and Julian Dashper (at Hamish McKay Gallery, Wellington, in 2008)—despite their being fully cheese to his chalk.

In the 1990s, Mrkusich would find himself eclipsed by Walters, whose standing was paradoxically enhanced by the cultural-appropriation debate, even though he claimed his works were purely formal—as champions ran to Walters’s defence. He remains a live issue in the culture—there’s a Walters industry. Dunedin Public Art Gallery and Auckland Art Gallery have just done a major Walters show, and it’s touring to Te Papa. By contrast, Mrkusich’s last public outing was rather glorious, but four years ago and in Masterton!

Mrkusich was a resourceful, intelligent painter. His works were brainy and good looking. But, while he’s a key figure in our national art history, he aspired to an entirely different context—a different conversation, which never came. The dilemma remains: what to do with an internationalist whose work is only known on these islands; what to do with him in this postmodernist, post-formalist, post-medium, post-national moment; what to make of him, now?

•

Not Available at a Bookseller near You

.

A few months back, sojourning in New York, I was reading rave reviews of The Rhonda Lieberman Reader. I scoured the bookshops for a copy—to no avail. Amazon didn’t list it either. Frustrated, on my return to Wellington I contacted its boutique publisher, Pep Talks, directly. My copy has just arrived. Joy.

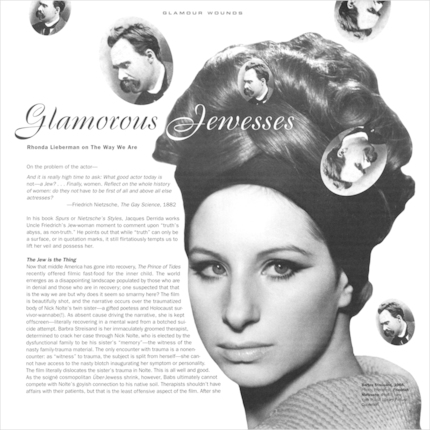

In the 1990s, I had the biggest reader crush on Lieberman. When Artforum arrived each month, her Glamour Wounds column was the first thing I’d read. Perhaps annoyingly, I’d read it aloud to my co-workers—some of whom appreciated my guilty pleasure.

Lieberman wrote sharp art pieces—her essay, ‘The Loser Thing’, brilliantly mapped the emerging abject Zeitgeist in American art. But, her Glamour Wounds columns were mostly about other stuff: Barbie and Barbra Streisand, Sandra Bernhard and Thomas Bernhard, Roseanne Barr and Coco Chanel, being a model for a day and teaching in Sweden, Miami’s Fontainebleu Hotel and grunge. Each revealed a new vector of personal interest, pleasure, and pain, triangulating her. Reading her, I thought I knew her.

Lieberman was Ivy-League educated, bookish but bratty, chatty, catty, and altogether ‘too Jewish’. She missed no opportunity to drop Yiddish slang. Her self-deprecating anecdotes invited sympathy, but her off-the-cuff observations had cruel cut through. She was a breath of fresh air. I wanted to write like that, even if it wasn’t me.

Here’s my favourite bit from ‘The Coldest Profession’: ‘Since I daylight as a pedagogue, getting into heavy textual discussions with any schmendrick who can get into a seminar, my ethical high road has more than a slight odor of the world’s oldest profession. I greet often clumsy advances responsively, indulge freakish trains of thought with the poker face of a hardened pro, shamelessly encourage the boring, and treat half-baked gibberish as if it were a cogent point, saving the client’s face by making him seem sentient and desirable before the group … The distinction between prostitute and professor is finer than we suspect.’

Glamour Wounds felt purposefully out of place in Artforum. But, while the column was unique, it was also timely. Published between 1992 and 1995—years that bracketed the 1993 Whitney Biennale—it resonated against the rise of identity politics. That moment favoured the worthy, personal testimony of marginalised Others. But how could you get a look in if you’re privileged—not invited to the pity party? Lieberman’s solution: join them anyway. Recast your privilege as pain, your subcultural passion as cultural oppression, and your singularity as marginality. ‘Glamour Wounds’ said it all.

Happily, I got to meet Lieberman. On a trip to New York—in late 1994, I think—I looked her up. She suggested a drink at the Algonquin Hotel, so we could sit in the room where Dorothy Parker and the Vicious Circle once held court. There, I felt at home, a million miles from home.

Later, after I returned to wet, dismal Dunedin, the highlight of my year would be the interruption of a Gallery staff meeting: ‘Robert, telephone. It’s Rhonda Lieberman.’ I felt like Cinderella, surrounded by ugly sisters, being handed my glass slipper. The reason for her call? She was concocting an identity-politics-mocking assignment for her Swedish art-school students, prompting them to address a cliched export property perennially used to characterise their country—Ingmar Bergman. ‘Is there a New Zealand equivalent?’, she asked. Is there what.

The Rhonda Lieberman Reader, ed. Sarah Lehrer-Graiwer (Los Angeles: Pep Talk, 2018). Order here.

•

Who Am I?

I am a contemporary-art curator and writer, and Director of the Institute of Modern Art, Brisbane. I have held curatorial posts at Wellington’s National Art Gallery, New Plymouth’s Govett-Brewster Art Gallery, Dunedin Public Art Gallery, Auckland Art Gallery, and, most recently, City Gallery Wellington, and directed Auckland’s Artspace. My shows include Headlands: Thinking through New Zealand Art for Sydney’s Museum of Contemporary Art (1992); Action Replay: Post-Object Art for Artspace, Govett-Brewster Art Gallery, and Auckland Art Gallery (1998); and Mixed-Up Childhood for Auckland Art Gallery (2005). My City Gallery shows include Yvonne Todd: Creamy Psychology (2014), Julian Dashper & Friends (2015), Francis Upritchard: Jealous Saboteurs (2016), Colin McCahon: On Going Out with the Tide (2017), John Stezaker: Lost World (2017), This Is New Zealand (2018), Iconography of Revolt (2018), Semiconductor: The Technological Sublime (2019), Oracles (2020), Zac Langdon-Pole: Containing Multitudes (2020), and Judy Millar: Action Movie (2021). I curated New Zealand representation for Brisbane’s Asia-Pacific Triennial in 1999, the Sao Paulo Biennale in 2002, and the Venice Biennale in 2003 and 2015. I am co-publisher of the imprint Bouncy Castle.

Contact

BouncyCastleLeonard@gmail.com

+61 452252414

This Website

I made this website to offer easy access to my writings. Texts have been edited and tweaked. Where I’ve found mistakes, I’ve corrected them.

.