.

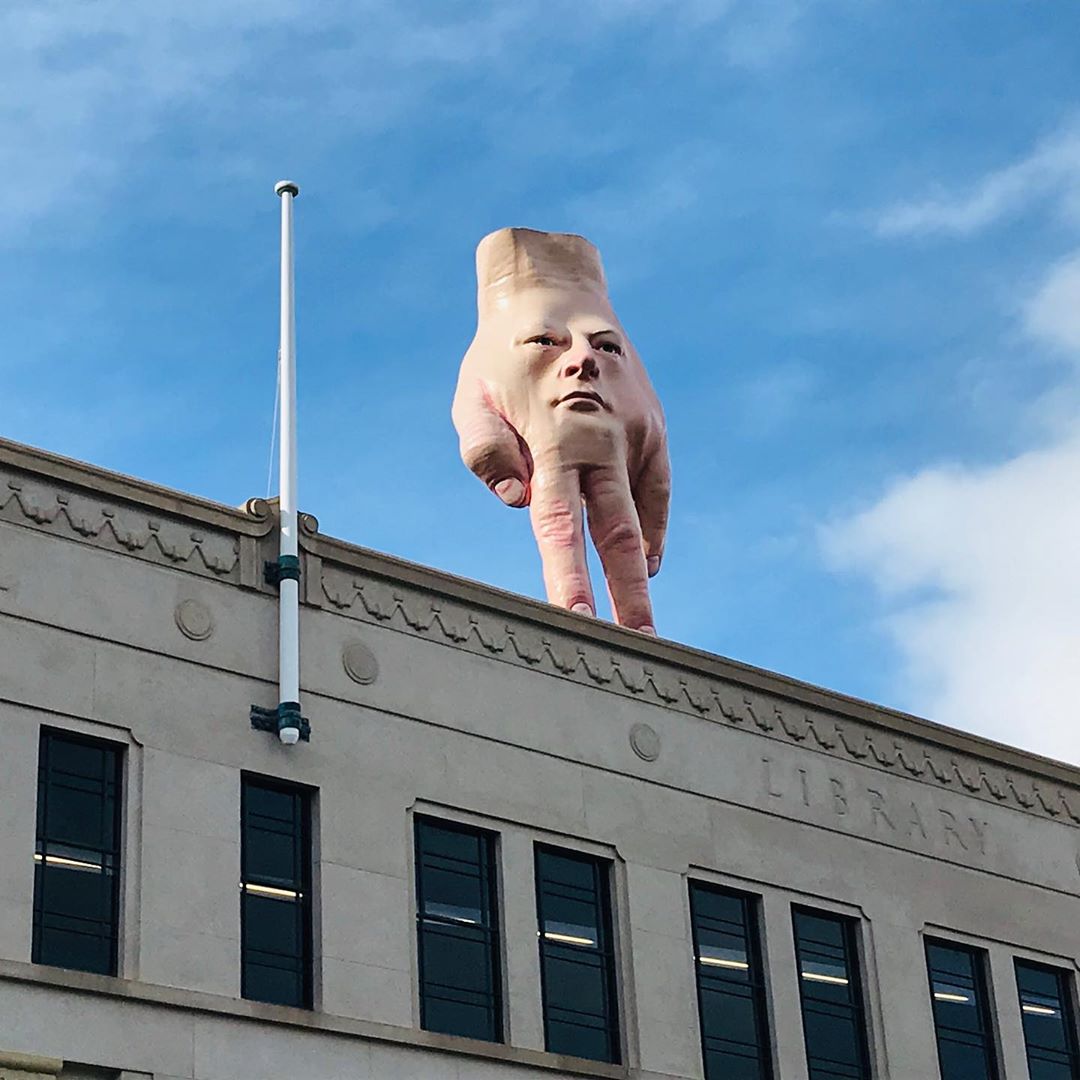

I’ve just been in Sydney, where I kept bumping into Australian painter Imants Tillers and his work. Tillers is famous for colliding imagery appropriated from other artists on arrays of canvasboards. He’s been making these works for almost forty years now. In Sydney Contemporary, his work was in the Arc One booth. He also had a solo show at Roslyn Oxley’s Paddington gallery—work produced in the wake of his recent survey show in Riga. (I attended an event at Oxley’s, where Tillers spoke with Power Institute Professor Mark Ledbury—Power published the book for the Riga show.) Tillers also has an installation at Art Gallery of New South Wales, in connection with their show Making Art Public: Fifty Years of Kaldor Public Art Projects. That work addresses the first Kaldor project, Christo’s Wrapped Coast at Sydney’s Little Bay, in 1969. Tillers, then an architecture student, was a helper on the project, and the experience inspired him to become an artist. In Making Art Public, Tillers is also name checked as one of the three artists showcased in Kaldor’s eighth project, 1984’s An Australian Accent show at PS1, New York, and the Corcoran, Washington DC. In Sydney in September, there was no getting away from Tillers.

Tillers is an enduring figure in Australian art. His project has surfed and survived art-world fashion waves and paradigm shifts and it’s still standing. Discussion around it continues, although not as furiously as in the 1980s. Indeed, from the outset, Tillers’s work was engineered to be hardy—to escape irrelevance. It bridged antithetical tendencies—conceptualism and neoexpressionism. It deconstructed Australianness while epitomising an Australian condition. Peppered with references to Tillers’s Latvian-refugee heritage, it was ‘death of the author’ appropriation with an identity-politics twist. Etcetera. Tillers always had it both ways—with wiggle room. That’s why he complicated so many arguments, and why he continues to be relevant as arguments turn.

Tillers frames art history as much as being framed by it. His work makes me think about how we all read art in our own way. There’s the canon, the more-or-less shared story of art—the map we all refer to. However, each of us makes our own personal journey through art, based on what is to hand, coming to this or that artist or work in our own time in our own way, in a peculiar order, making our links for ourselves, tracing our own personal art history. Tillers’s work reifies his personal journey through art, as driven by his curiosity and idiosyncratic sensibility. He collages and entwines canonical art that everyone knows (Georg Baselitz or Giorgio de Chirico, perhaps) with the local (Aboriginal desert painting, say) and with art particular to his own background (Latvian art). Tillers’s art is akin to psychogeography; his sensibility is revealed even as he drifts, gets lost and distracted. His work is made entirely of other artists’ imagery, but the distinctive web of connections is uniquely him—a fingerprint.

One of Tillers’s new paintings at Oxley—Nature Speaks: GQ (2019)—features a quote from Buddha: ‘You cannot travel on the path before you have become the path itself.’ You could say Tillers has traversed art history by becoming art history.

•