.

There’s a memorable scene in John Ford’s 1956 western The Searchers. Ethan (John Wayne) is on a mission. He’s trying to rescue his niece (Natalie Wood) from the Comanche, who abducted her. While on their trail, he discovers the corpse of one of them and shoots out his eyes. The Reverend Clayton scolds him for being needlessly violent, but doesn’t know the half of it. The sadistic Ethan explains that he wanted to guarantee that the dead man could not pass into the afterlife, saying, ‘But what that Comanche believes, ain’t got no eyes, he can’t enter the spirit land. Has to wander forever between the winds. You get it, Reverend?’ It is a reminder that while understanding one another can enable greater sensitivity it can also enable greater insensitivity—or is it a more culturally sensitive insensitivity?

•

Time to Kill? Lockdown Puzzle!

Deaths of the Artists

Bas Jan Ader, Jean-Michel Basquiat, Aubrey Beardsley, Chris Burden, Keith Haring, Eva Hesse, Yves Klein, Édouard Manet, Ana Mendieta, Amedeo Modigliani, Pierre Molinier, Jackson Pollock, Egon Schiele, Georges Seurat, Robert Smithson, Vincent van Gogh, Andy Warhol, and Francesca Woodman. Match the names to their epitaphs.

.

22, suicide by defenestration. Said, ‘You cannot see me from where I look at myself.’

.

25, tuberculosis. Dandy. Said, ‘I have one aim, the grotesque. If I am not grotesque I am nothing.’

.

27, heroin overdose. His tag was a crown.

.

28, Spanish flu. Said, ‘He who denies sex is a filthy person who smears in the lowest way his own parents who have begotten him.’

.

31, meningitis. Said, ‘Some say they see poetry in my paintings; I see only science.’

.

32, AIDS. ‘Crack is wack.’

.

33, presumed lost at sea. Emo.

.

34, from his third heart attack in two months. Said, ‘Blue has no dimensions.’

.

34, brain tumours. Said, ‘Don’t ask what the work is. Rather, see what the work does.’

.

35, plane crash. Said, ‘Abstraction is everybody’s zero but nobody’s nought.’

.

35, tubercular meningitis. His widow—eight months pregnant with the couple’s second child—committed suicide by defenestration the following day.

.

36, fell from her thirty-fourth-floor apartment. Her artist husband of eight months was acquitted—twice. In one of her performances, she had held a freshly decapitated chicken by its feet as its blood spattered her naked body.

.

37, probable suicide, by gunshot. Said, ‘The sight of the stars makes me dream.’

.

44, car crash. Said, ‘I am nature.’

.

51, eleven days after his gangrenous left foot was amputated due to complications with syphilis and rheumatism. Painted a dead toreador.

.

58, arrhythmia, following a routine gall-bladder operation. Said, ‘Death is the most convenient time to tax rich people.’

.

69, melanoma, after near misses with gun and electrocution, and being crucified on a car. Said, ‘Nail me to my car and I’ll tell you who you are.’

.

75, suicide by hanging. The note said, ‘I’m taking my life. The key is with the concierge.’

.

Answers here.

.

[IMAGE: Vincent Van Gogh Skull of a Skeleton with Burning Cigarette c.1885–6]

•

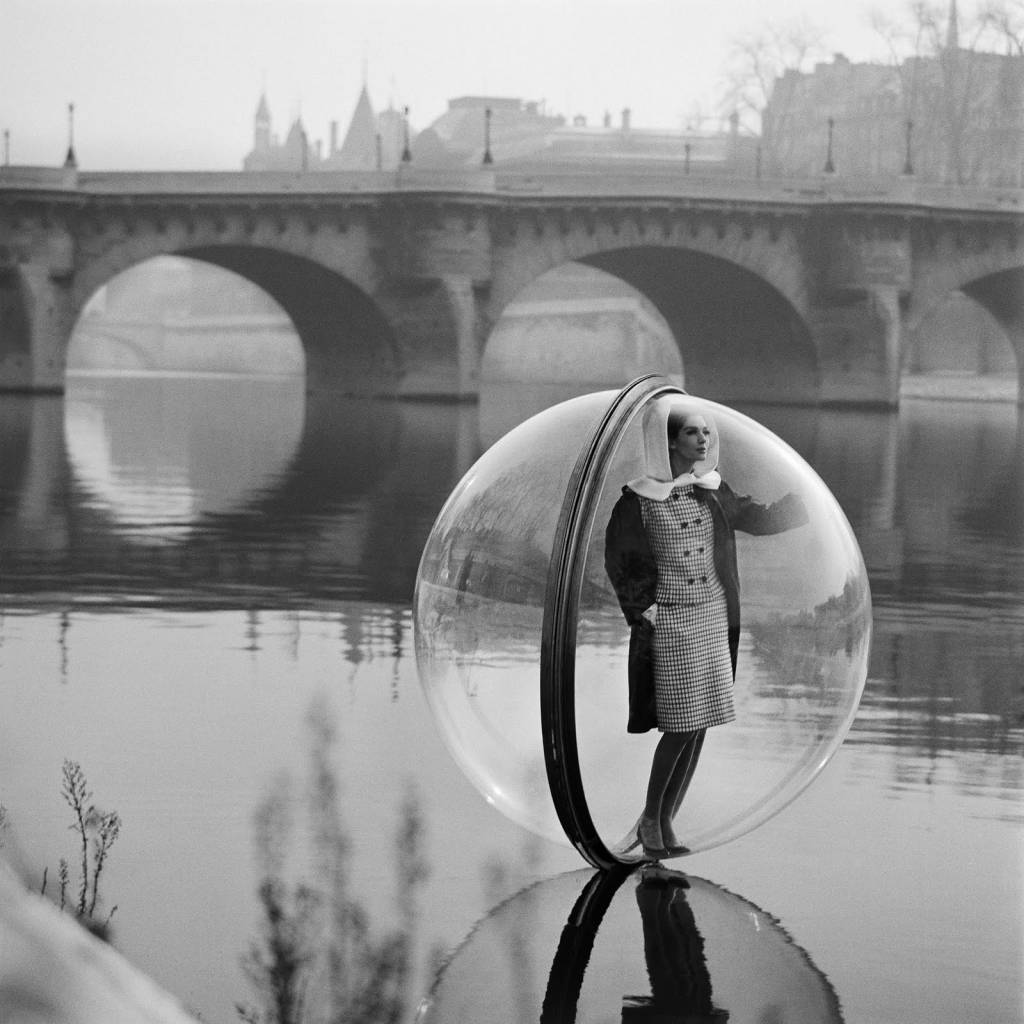

Bubble

.

I’ve always loved Melvin Sokolsky’s fashion-photo series The Bubble, published in Harper’s Bazaar in 1963. It seems especially resonant right now, with us all in our bubbles. Model Simone d’Aillencourt floats through Paris, encased in a Plexiglass ball. She appears to be at once inside and outside the scene, an object of the gaze yet also the embodiment of the gaze within the image—like us, a tourist.

•

Who Am I?

I am a contemporary art curator and writer, and Director of the Institute of Modern Art, Brisbane. I have held curatorial posts at Wellington’s National Art Gallery, New Plymouth’s Govett-Brewster Art Gallery, Dunedin Public Art Gallery, Auckland Art Gallery, and, most recently, City Gallery Wellington, and directed Auckland’s Artspace. My shows include Headlands: Thinking through New Zealand Art for Sydney’s Museum of Contemporary Art (1992); Action Replay: Post-Object Art for Artspace, Govett-Brewster Art Gallery, and Auckland Art Gallery (1998); and Mixed-Up Childhood for Auckland Art Gallery (2005). My City Gallery shows include Yvonne Todd: Creamy Psychology (2014), Julian Dashper & Friends (2015), Francis Upritchard: Jealous Saboteurs (2016), Colin McCahon: On Going Out with the Tide (2017), John Stezaker: Lost World (2017), This Is New Zealand (2018), Iconography of Revolt (2018), Semiconductor: The Technological Sublime (2019), Oracles (2020), Zac Langdon-Pole: Containing Multitudes (2020), and Judy Millar: Action Movie (2021). I curated New Zealand representation for Brisbane’s Asia-Pacific Triennial in 1999, the Sao Paulo Biennale in 2002, and the Venice Biennale in 2003 and 2015.

Contact

BouncyCastleLeonard@gmail.com

+61 452252414

This Website

I made this website to offer easy access to my writings. Texts have been edited and tweaked. Where I’ve found mistakes, I’ve corrected them.

.