.

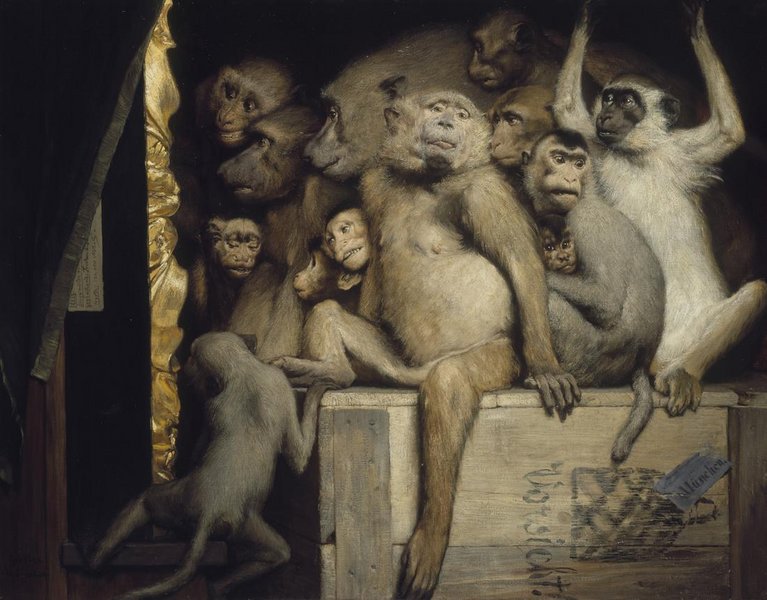

Gabriel von Max was an oddball nineteenth-century Czech-born German painter. He was rated for his religious paintings, but he spent much of his time painting monkeys—considered an inferior pursuit at the time. He even earned the title ‘Affenmaler’—monkey painter. In this 1889 painting, he presents his furry friends as a cohort of art critics. They strike poses: grandiose, quizzical, and imbecilic. They are us, yet not us. Perhaps it was a trap for anyone who dared to judge his own work, with Von Max holding up a mirror to his critics. As a curator—straddling the realms of art production and reception—I don’t know whether to take it personally. Which side of the fence am I on? Am I among the critics (judging the art) or at their mercy (making exhibitions alongside the artists)? No offence to monkeys.

.

[IMAGE: Gabriel von Max Monkeys as Judges of Art 1889]

•

Poetic Justice

.

If I won Lotto, I would endow a writing prize for premature obituaries. I’d invite writers to pen obituaries for living persons of note, assuming they will die five years from now. The writers will have to be true to what has already occurred, but can invent the future as fancifully as they wish, perhaps granting their subjects the last chapters and deaths they deserve—flattering or otherwise. Get creative. We publish the best.

[IMAGE: Henry Wallis The Death of Chatterton 1856]

•

Post Hoc

.

As soon as we went into lockdown (the first time), I began missing the art life. I wondered when galleries would reopen. I wondered when borders would reopen and artists and curators from elsewhere would be visiting, bringing energy and information. I wondered when I might be back on planes, visiting art capitals, grazing biennales, doing business. Now I’m thinking—if and when borders reopen—will there even be biennales, art capitals, and art as we know it? Will the game have changed, fundamentally?

Isolation has always been a problem for New Zealand artists. Last century, they enjoyed local careers—international opportunities were exceptional, the icing. But, in the last twenty years, our art system has become predicated on working internationally, changing the scale and scope of our art—the dynamics of production and reception, the rewards. Consider Mata Aho, whose work was picked up early for Documenta and is now shaped by international exhibitions and the opportunities they bring. Internationalism has enabled our artists to be part of more complex and more specialised conversations.

Since 2001, New Zealand has been sending artists to Venice to help springboard them (and us) into the international discussion, the big league. In 2019, we sent Dane Mitchell. His show Post Hoc—tellingly concerned with things that have become extinct—was immediately followed by the pandemic. Like many of our successful artists, Mitchell faces losing momentum as opportunities to work internationally dry up, making it hard to capitalise on Venice. The timing couldn’t be worse for him. Indeed, the pandemic’s implications may hit hardest our most ambitious artists—who have already outgrown what New Zealand can offer, resource-wise, audience-wise.

What can be done? I was once advised that there are three responses to crises: resist, succumb, and exploit. Should we stay the course with our internationalism (double down)? Should we adjust to having a more intimate, enclosed, domestic scene (as in the 1980s, say)? Or are there also opportunities hidden in our current fraught moment? What role will agencies and individuals play in fronting this discussion and in the work that follows?

•

Who Am I?

I am a contemporary art curator and writer, and Director of the Institute of Modern Art, Brisbane. I have held curatorial posts at Wellington’s National Art Gallery, New Plymouth’s Govett-Brewster Art Gallery, Dunedin Public Art Gallery, Auckland Art Gallery, and, most recently, City Gallery Wellington, and directed Auckland’s Artspace. My shows include Headlands: Thinking through New Zealand Art for Sydney’s Museum of Contemporary Art (1992); Action Replay: Post-Object Art for Artspace, Govett-Brewster Art Gallery, and Auckland Art Gallery (1998); and Mixed-Up Childhood for Auckland Art Gallery (2005). My City Gallery shows include Yvonne Todd: Creamy Psychology (2014), Julian Dashper & Friends (2015), Francis Upritchard: Jealous Saboteurs (2016), Colin McCahon: On Going Out with the Tide (2017), John Stezaker: Lost World (2017), This Is New Zealand (2018), Iconography of Revolt (2018), Semiconductor: The Technological Sublime (2019), Oracles (2020), Zac Langdon-Pole: Containing Multitudes (2020), and Judy Millar: Action Movie (2021). I curated New Zealand representation for Brisbane’s Asia-Pacific Triennial in 1999, the Sao Paulo Biennale in 2002, and the Venice Biennale in 2003 and 2015.

Contact

BouncyCastleLeonard@gmail.com

+61 452252414

This Website

I made this website to offer easy access to my writings. Texts have been edited and tweaked. Where I’ve found mistakes, I’ve corrected them.

.