.

These days, I receive few invitations to weddings, but many to funerals. Too many. I was sad to hear of the recent death of Robert MacPherson, a giant of the Brisbane art scene. True, he had a good innings—he was eighty-four! MacPherson was a complex, eccentric artist, who jumped many art-category fences, scrambling formalism, conceptualism, and folksy Aussie vernacularism. He was at once an internationalist and a localist. He did a poignant show for me at the Institute of Modern Art, back in 2007. Popov and the Lost Constructivists filled the big gallery with his constructivist-inspired junk assemblages. These were accompanied by death notices from the local newspaper glued to drops of receipt-printer paper. (He had started by cutting out obits for Russian immigrants, but expanded to include others with nicknames.) The work implied that countless Russian émigré constructivists may have been working incognito in Brisbane backyard sheds. Of course, MacPherson himself did not toil in obscurity. Today, he pretty much permeates Australian art history. He was a big wheel.

.

[IMAGE: Robert MacPherson: Popov and the Lost Constructivists, Institute of Modern Art, Brisbane, 2007.]

•

Pharmakon

.

There’s a lot of clamour around ‘art history’ right now. On the one hand, universities are cutting art-history departments—it’s part of the neoliberal purge of the humanities, we’re told. On the other hand, art history is under attack from the left—as a bastion of crusty white privilege. Of course, when people talk about ‘art history’, they are often talking about very different things. For many people, ‘art history’ conjures up notions of the canon, and the image of Lord Kenneth Clark in his tweed jacket fronting the 1969 BBC TV show Civilisation, laying out the Western high-art tradition. (I was six.) However, we tend to forget that, just three years later, in 1972, BBC2 screened John Berger’s Ways of Seeing—a Marxist-feminist critique of Civilisation. (I was nine.) When I started studying art history at the University of Auckland in the early 1980s (still a teenager), it was still all about the Western tradition (white males), and, to proceed to post-grad, you had to study a European language (French, German, Italian, or Spanish). However, all that was rapidly coming unstuck. A Women in Art paper was introduced (which I did), followed (after I left) by papers on New Zealand art, contemporary art, and Maori and Pacific art. Today’s art-history courses bear little resemblance to the one I did. Similarly, in my later life in art museums, art history would be always under scrutiny while being furiously transformed. For as long as I have been involved in it, art history has been in a state of perpetual and profound revision, philosophical and political expansion. Indeed, for me, art history is that business of rewriting. Art history may be, at once, the field and the game that’s played upon it; poison and cure, scapegoat and straw man. Pharmakon.

.

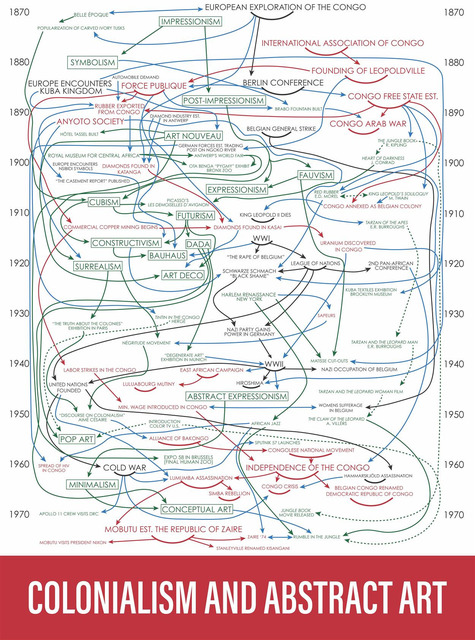

[IMAGE: Hank Willis Thomas Colonialism and Abstract Art 2019]

•

Today Is the First Day of the Rest of My Life

.

I’m no longer at City Gallery Wellington, however I hope you get to see my four current shows, which opened there yesterday: Brett Graham: Tai Moana Tai Tangata, Judy Millar: Action Movie, Tia Ranginui: Gonville Gothic, and Pierre Huyghe: Human Mask (until 31 October). People have been asking me about my plans. For now, I’m focusing on writing and publishing. I’ve joined Art News New Zealand as Editor and I’ll be revving up my work on Bouncy Castle. Our second title—Giovanni Intra: Clinic of Phantasms—is almost off to the printers. It’s being co-published with Semiotext(e). Two more books are in the pipeline. I’m also looking for opportunities to curate and consult; advise and assist; write and edit. I can be contacted on my new email BouncyCastleLeonard@gmail.com. Don’t be shy.

.

[IMAGE: Salad days. I enjoy a light lunch at Villa Blanca, Beverly Hills, Los Angeles, alongside its owner Lisa Vanderpump, 2016. Photo: Michael Zavros.]

•

Who Am I?

I am a contemporary art curator and writer, and Director of the Institute of Modern Art, Brisbane. I have held curatorial posts at Wellington’s National Art Gallery, New Plymouth’s Govett-Brewster Art Gallery, Dunedin Public Art Gallery, Auckland Art Gallery, and, most recently, City Gallery Wellington, and directed Auckland’s Artspace. My shows include Headlands: Thinking through New Zealand Art for Sydney’s Museum of Contemporary Art (1992); Action Replay: Post-Object Art for Artspace, Govett-Brewster Art Gallery, and Auckland Art Gallery (1998); and Mixed-Up Childhood for Auckland Art Gallery (2005). My City Gallery shows include Yvonne Todd: Creamy Psychology (2014), Julian Dashper & Friends (2015), Francis Upritchard: Jealous Saboteurs (2016), Colin McCahon: On Going Out with the Tide (2017), John Stezaker: Lost World (2017), This Is New Zealand (2018), Iconography of Revolt (2018), Semiconductor: The Technological Sublime (2019), Oracles (2020), Zac Langdon-Pole: Containing Multitudes (2020), and Judy Millar: Action Movie (2021). I curated New Zealand representation for Brisbane’s Asia-Pacific Triennial in 1999, the Sao Paulo Biennale in 2002, and the Venice Biennale in 2003 and 2015.

Contact

BouncyCastleLeonard@gmail.com

+61 452252414

This Website

I made this website to offer easy access to my writings. Texts have been edited and tweaked. Where I’ve found mistakes, I’ve corrected them.

.