(with Caroline Vercoe) Art Asia Pacific, no. 14, 1997.

Auckland is the biggest Polynesian city in the world. Here, young New Zealand–born Pacific Islanders grow up with a mix of cultural messages: alongside the traditions of their parents and grandparents—incorporating dancing and feasting, Christian morality and family values—are the influences of hip-hop and the op shop, streetwear and the Paris collections, Andy Warhol superstars, drag queens, and gay bars. In this space, a new kind of feral art practice is found in the clubs and galleries, on the catwalk and in the media. Marked by the collaboration of designers, models, artists, musicians, and photographers, this ‘Pasifika’ blends Pacific Island and western forms.

One of the epicentres of the phenomenon is the Pacific Sisters, a loose collective whose members come from different Pacific Island and Maori backgrounds. Almost all are New Zealand born. They have been around for about five years, although the line-up has changed.1 These sisters (and some brothers) work together, organising shows, productions, and performances, supporting each other, and creating a platform for Pacific Island talent. The Sisters write scripts, cast models and performers, and collaborate with musicians. The productions can be huge. The show at Auckland Town Hall for Pasifika ’94 reputedly featured five bands, twenty-five designers, and a cast of 175.

The Sisters come together for group projects but they also work as individuals in the art, education, and fashion arenas. Among them are Lisa Reihana, a filmmaker and multimedia artist who also teaches at Manukau Polytechnic; artist Ani O’Neill, whose work was seen in the recent Asia-Pacific Triennial; and Rosanna Raymond, who has a long history in the fashion and casting industries. Rosanna is a spokesperson for the Sisters …

.

Pacific Sisters is ever evolving, it’s never static, it’s multi-disciplinary. We’re like a Polynesian version of Andy Warhol’s Factory: artists, designers, fashion, street, people.2

.

Rosanna produced the first Pasifika fashion show in 1992, and many of those involved form the current core group of Pacific Sisters. Accompanied by hip-hop music from DJ DLT, models and performers stormed onto the catwalk, introducing a New Zealand take on Pacific Island design. Designs ranged from mu’u mu’u (conservative ‘Mother Hubbard’ dresses) and tapa skirts to see-through chiffon and black stockings with suspenders. Audience opinion was polarised, especially by the more revealing and risque garments. Pacific Island culture is heavily influenced by Christianity and, consequently, for young women exposure of the body is discouraged in favour of graceful modesty. The mixture of traditional elements with strident sexiness proved controversial.

.

We’ve spent a long time on the edge. We confuse a lot of people because we are all mixed. We’re not a Maori group or a Samoan group, we’re multicultural. Some have a huge problem with that. It’s a generation thing too, a clash of eyes: old eyes, young eyes.

.

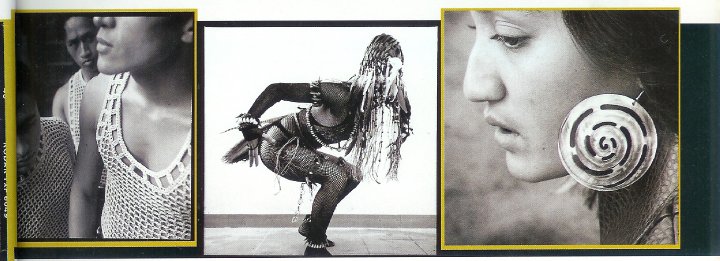

The Sisters assert both their Pacific Island and Pakeha identities. While western ideas and references have long been absorbed into costuming in the Islands, the Sisters’ work is something else again. In Pacific Island body adornment, western influence is seen in the incorporation of non-traditional materials, such as brightly coloured plastics and sequins, into traditional garments. The Sisters, on the other hand, enlist traditional materials—feathers, tapa, shells—to create costumes which, while tipping their hat to tradition, go beyond tradition.

The Sisters also reinflect western-style garments. This kind of displacement can be seen in the fashion spread, ‘Pacific Rap’, published in Planet magazine in 1993.3 In one of the photographs, styled by Rosanna and photographed by honorary Sister, Greg Semu, Maori model Bonny Proctor wears an Alan Preston papa shell-and-frangipani necklace as a head adornment, a Pacific Sisters coconut choker, a crochet shawl ‘made to order by Viv’, a crochet skirt, a stretch top from St Vincent de Paul, Fila shoes from Paris Texas, and carries a kete, a shoulder bag or basket. The image recalls nineteenth-century black-and-white ethnographic photographs: the crochet shawl resembles a tufted cloak, with the skirt worn in the manner of a lava lava (sarong). Apparently without irony, the text accompanying the spread reads: ‘In tribute to all the indigenous people of the world and their dedication to the preservation of their tribal culture.’

If the Sisters offer their work as a celebration of an Islands design, they also camp it up and make it their own. Their clash-of-the-codes styling echoes high fashion, where different brands of costume are grafted and misused, recontextualised and recoded, for effect. But while Western fashion designers such as Jean-Paul Gaultier present ethnic gear as fantasy, fancy dress, and exotica, the Sisters offer their work as a taste of their identity. But, if their work represents something authentic, perhaps it is less truth to tradition than truth to the Sister’s present situation, as Pacific Islanders living not in the Islands but in the biggest city in New Zealand.

.

We follow the ancient way of working from the environment. We get our inspiration from our immediate urban/media environment. We don’t stare at coconut trees—we stare at motorways.

.

In 1994, the touring exhibition Bottled Ocean brought a new generation of New Zealand-born Pacific Island artists to public attention. The show included Ani O’Neill and Greg Semu, and the Sisters were commissioned to perform at the opening at Auckland City Art Gallery. Wearing costumes that referred to characters from Pacific Island legends, they mingled with the crowd, telling stories and highlighting the importance of oral history and performance in Pacific art. This project developed into a larger production for Auckland’s 1995 Interdigitate video-wall event, a presentation of the Mangaian Island version of the legend of Ina and Tuna.

There are several versions of this story in the Pacific. In the Mangaian version, a beautiful woman, Ina, regularly bathes in a pool full of eels. Tuna, the king of eels, desires her. He enters her vagina with his tail and is transformed into a handsome man. Later, Tuna sees his own death in a dream of a storm. He explains the prophesy to Ina and says that she must chop off his head and plant it. She does this and it grows to feed her people. This is the origin of the coconut.

The Sisters performed this legend against a thirty-six monitor video wall programmed by Lisa Reihana, and a soundtrack of music and water. Ani played Ina, in a floral polyester and woollen dress with a hand-printed tapa overskirt. Rosanna played Tuna, with a coconut shell puppet attached to her arm, painted body tattoos and a hula skirt made out of videotape, which gave the impression of water.

.

Old legends: I’m a legend freak—tapa, flax, feathers! When the missionaries took away our rituals they took away the need for costumes. We’ve created rituals. A lot of our costumes tell stories. We made costumes for Ina and Tuna because we’re doing a story. If you just look at them as frocks, it wouldn’t make sense.

.

Mika, the notorious Maori drag star, has featured in many of the Sisters’s extravaganzas. For the 1996 Interdigitate event, he performed his song ‘Lava Lover’ wearing a Sisters creation: a videotape underskirt, a bright red hula-tutu, raffia armbands, and a pointy coconut lava-engraved bra with ‘volcanic’ red raffia spurting from the nipples. The Sisters also collaborated on his cabaret. The Sisters often work with drag queens and fa’afafine (Samoan men who live as women). Just as they play with notions of sexual identity, and gender, the Sisters also play with notions of cultural identity, sometimes verging on a kind of cultural drag. With its playful, subversive mismatches, their work could be described as carnivalesque.

.

I have this term: ‘art blah blah’. They all come in and take a slice, over-intellectualise blah blah blah. This has no relation to the way we work. The process of intellectualising kills the moment. The moment and the experience is what’s important, not the intellectual part.

.

Last year, after extensive fundraising, the Sisters were able to realise a dream. They took a huge crew, including family, friends, roadies, designers, artists and performers to Western Samoa for the Seventh Pacific Festival of Arts. The Sisters planned to present their pageant (featuring New Zealand hip-hop music, a video show and a wardrobe of frocks), singer Henry Ah-Foo Taripo, and the whole Ina and Tuna production.

They were hosted for three weeks by Sister Fiona Wall’s family village in Malie. Fiona was invited to be the taupou (a young female representative of the village) at the kava ceremony as a representative of her family. She dressed in true Pacific Sisters fashion. Instead of the usual purple velvet worn by the taupou of Malie, she wore a banana leaf headdress adorned with pheasant feathers, Pacific Sisters jewellery made from flax, tapa, paua shells and feathers, a handprinted lava lava dress by Jean Clarkson, a shell and pu‘a seed–beaded waistcoat, and a raffia and scallop shell hula skirt. This was a big moment for the Pacific Sisters, as their style was accepted by the village within this traditional ceremony.

Unfortunately, bad weather caused the cancellation of the Ina and Tuna performance, but the Sisters’ multimedia fashion extravaganza was staged over two nights at the Hotel Tusitala. The Sisters recruited local Samoan models and designers. The show featured seventeen designers, a video component and DJs; there were painted-on moko, leis transformed into boas, a guy with a massive afro in a superman suit breakdancing and aiming a banana at the crowd, girls in stretchy lycra shorts with tatau (tattoo) designs, muscled guys in shades and lava lava, and fa’afafine in cocktail numbers. The pageant concluded with a parody segment in which ‘an artist’ directed colourfully frocked Sisters, who composed themselves demurely, reclining on the fala (floor)—appropriating a stock colonial male fantasy. Meanwhile, Ani O’Neill performed a Rarotongan dance. And finally, Greg Semu, planted in the audience, was coaxed on stage to take their picture.

.

Gauguin, dusky maiden, Miss Polynesia pageant, long-haired Polynesian girls, shells, floral frocks—everything you’d see on a postcard. It was taking the piss, a bit of a pose, a giggle. We love to pose.

- All italicised quotations are from an interview with Rosanna Raymond, by the authors, November 1996.

- Key members include Rosanna Raymond, Fiona Wall, Selina Forsyth, and Greg Semu (Samoans); Ani O’Neill and Karlos Quartez (Cook Islanders); and Suzanne Tamaki, Niwhai Tupaea, Toni Symons, and Lisa Reihana (Maori).

- Planet, no. 11, Winter 1993: 27.