www.abc.net.au, 2013.

Hannah Mathews interviews Robert Leonard.

•

In 2005, Robert Leonard moved from New Zealand to Australia to take up the directorship of the Institute of Modern Art, Brisbane. Leonard is one of New Zealand’s most experienced contemporary art curators. He has worked in a range of capacities in art museums and contemporary art spaces, including a stint as Director of Artspace, Auckland (1997–2001). In 1992, Leonard collaborated with Bernice Murphy on the landmark exhibition Headlands: Thinking through New Zealand Art. Reviewing the show, John Daly-Peoples wrote: ‘Headlands will be reviled, revisited, reinterpreted and reassessed, but ultimately it will be the significant exhibition of the nineties having marked out the points of reference for the next decade.’ Leonard got the art bug at nine years of age after his father took him to see Surrealism, the Museum of Modern Art touring show, at Auckland City Art Gallery in 1972. According to Leonard, ‘That show left me with the idea that art’s job is to offer an alternative account of the world and I guess that is still essentially how I see it.’

Hannah Mathews: How did you get into curating?

Robert Leonard: I did a curatorial internship at the National Art Gallery (NAG) in Wellington in 1985. It was good timing. The Director, Luit Bieringa, had transformed the NAG from a dusty old place into something quite contemporary. He was building an international photography collection and bringing in sharp shows via Australia. That year, I helped install The British Show, from the Art Gallery of New South Wales. With my internship, there was no formal curatorial training. I spent time in various departments (registration, conservation, education, the print room, etc), and learnt by osmosis. The NAG’s curators were mostly old-school art historians. They weren’t interested in new developments in exhibition making, so there wasn’t much philosophical discussion. The most useful discussions I had were with people outside the institution, particularly Jim and Mary Barr, the Wellington collectors and freelance curators. Their house seemed to be the centre of the Wellington art world. After my internship, I was cut loose and did couple of freelance projects. I did Pakeha Mythology (1986) at New Plymouth’s Govett-Brewster Art Gallery. It was like an artist’s project. I made-over a gallery as a corporate boardroom, complete with wood panelling and a big table. Above the table, I hung three icons of New Zealand painting, Christopher Perkins’s Frozen Flame, Rita Angus’s Cass, and Colin McCahon’s Crucifixion with Lamp; nearby, a TV screened a compilation of ads featuring nationalist imagery. When they caught wind of it, the museum that lent the McCahon asked for it to be returned immediately, but were talked down. Pakeha Mythology was terribly self conscious. I fancied myself to be an enfant terrible. A little later, I got a job at the NAG, and soon I was working there as a curator.

What’s your approach to working with artists?

It’s hard to generalise. Artists are different and I work with them in different ways. In some projects, I am more in the driver’s seat; in others, more in the passenger seat. It depends on the artist and the project. It can be a pleasure to work with artists, but it can also be a pleasure not to. Artists can be very controlling, limiting the ways their work can be shown. When I started curating, people were excited by ‘the death of the author’ and wary of ‘the intentional fallacy’. The idea that artworks might operate outside the artist’s intentions gave curators a license to be willful, to provocatively juxtapose works in ways that the artists might not necessarily like. The curator was not expected to affirm the artist’s view, but could put it under pressure. You could test and challenge artists, holding up their works against the claims they made for them and presenting them in alternative contexts. Of course, that’s easier when you are working in a museum and you own the works, harder in a contemporary-art space where you are more dependent on artists for access to work. These days many curators talk as if their job is primarily to please artists—to represent and protect their interests. Keeping artists happy is important, but it’s not the only important thing. As a curator, there are times when you work for artists, times when you work alongside them, and times when you work against them. For a curator, it’s important to find opportunities to operate in all these registers. Curators need to be more than just artists’ enablers.

You’ve worked as a curator, but also as director of Auckland’s Artspace (1997—2001) and Brisbane’s Institute of Modern Art (since 2005). Do you see yourself more as a curator or a director?

I see myself as a curator-director rather than as a director-director. I became a director in order to have the freedom to curate. When I started working in museums in the mid-1980s, curators were in the directorate. But, in the early 1990s, with the advent of managerialism, they lost that privileged position. Now it’s their manager that gets invited to the meeting. It’s a shame that museum curators have become so marginalised.

So, are you happiest running contemporary art spaces or working in museums?

I move back and forth. The advantage of running a contemporary art space is that you can have an idea in the morning and make it happen in the afternoon, and you can shape everything holistically. The disadvantage is being undercapitalised, having a limited ‘indie’ audience, and being on a treadmill. I enjoy the creative freedom that comes from running my own show but I miss access to larger audiences.

You curated the New Zealand representation in the Asia Pacific Triennial (1999), Sao Paulo Bienial (2002), and Venice Biennale (2003). What have you found most rewarding about this?

It’s great to have the opportunity to work offshore in these contexts, to be part of these huge shows, but, usually, one is simply assisting artists on stand-alone projects. I’d love to do offshore projects which are more my own, where I am actively shaping them. I would relish the opportunity to make another Headlands-scale show, especially if I could have final cut.

The Asia Pacific Triennial (APT) is the biggest art show in Queensland. You have watched it evolve. How has it changed?

It has changed a lot. In the 1990s, the APT was instrumental in establishing the Asian contemporary art scene. It was where artists and curators from the region met and did business, and Brisbane artists and curators were part of that exchange. But after that, things changed. Asian artists and curators became more visible internationally, and no longer needed the APT as a platform. The Gallery brought the curatorial process in house, and started addressing the show less towards the art world, more towards maximising local general audiences, targeting families with things like Kids APT. These days, the APT draws huge audiences by specialising in entertaining G-rated art, art-as-spectacle, and the theme always seems to be ‘bigger than last time’.

So, you’re not a fan of blockbusters?

They have their place. Actually, I’ve always dreamed of doing a meta-blockbuster, a blockbuster about blockbusters. It’s called Salvador Dali vs. Damien Hirst. It’d be so popular. Dali and Hirst are from different moments, yet have much in common: sex and death, putrefaction, religion, dots—the big themes. Both exploited a popular idea of ‘the artist’, taking a radical model (the transgressive avantgarde provocateur) and transforming it into something conservative and complicit (the tabloid showman, the brand, kitsch). Both artists shamelessly courted the media and did films, jewellery, interior design, magazine covers, and merchandise; both got hooked on high-production values; both were in and out of step with the art world.

Many Queensland art institutions have faced uncertainty in the past nine months as the state government implements budget cuts. It has been argued that, in times of austerity, the agency of art increases. Certainly in the late 1970s and early 1980s, under Joh Bjelke-Petersen, one of Brisbane’s most exciting art scenes emerged.

I’m not from Brisbane, so I don’t share in that nostalgia for the post-punk Joh years. I guess you had to be there. While austerity may kill off some less interesting practices that depend on an overheated market, I have never subscribed to the view that it actually generates incisive art. Quite the reverse. In my view, art needs to be resourced, but intelligently. Anna Bligh’s government was seen as arts friendly. It put a lot of money into art, but much of that went on internally administered, politically-oriented projects that were about branding the government (like the Cairns Indigenous Art Fair, the Premier of Queensland’s National New Media Art Award, and public art), rather than on sharp artists and independent projects. As for the new government, we’re still waiting to see how things will shake down.

Art curatorship is a growing field, nationally and internationally. What are the directions and urgencies of the profession?

I’m concerned that the discussion is currently dominated by biennales. Broadsheet has largely become a journal of biennale commentary and criticism. I love going to biennales. They are excellent opportunities to see new work en masse and the growth and transformation of the biennale form is fascinating. But, in my experience, biennales rarely exemplify thoughtful, considered curating. Their typically grand but vapid themes are expressed in absurd titles, which are either feel-good and universalist (Plateau of Humankind and All Our Relations) or oxymoronic (The Dictatorship of the Viewer, Optimism in the Age of Global War, Spectacle of the Everyday, and Parallel Collisions). I get twitchy when biennale curators promote themselves as experts in everything, social-justice missionaries, and the embodiment of the world spirit, rather than be seen as operators, gatekeepers, and insider traders. Their messianic manifestos cloak art world realpolitik. It’s not that I think curators should limit their scope or ambition (because art can touch on anything and everything), but we need to dial back on ideology and hubris.

.

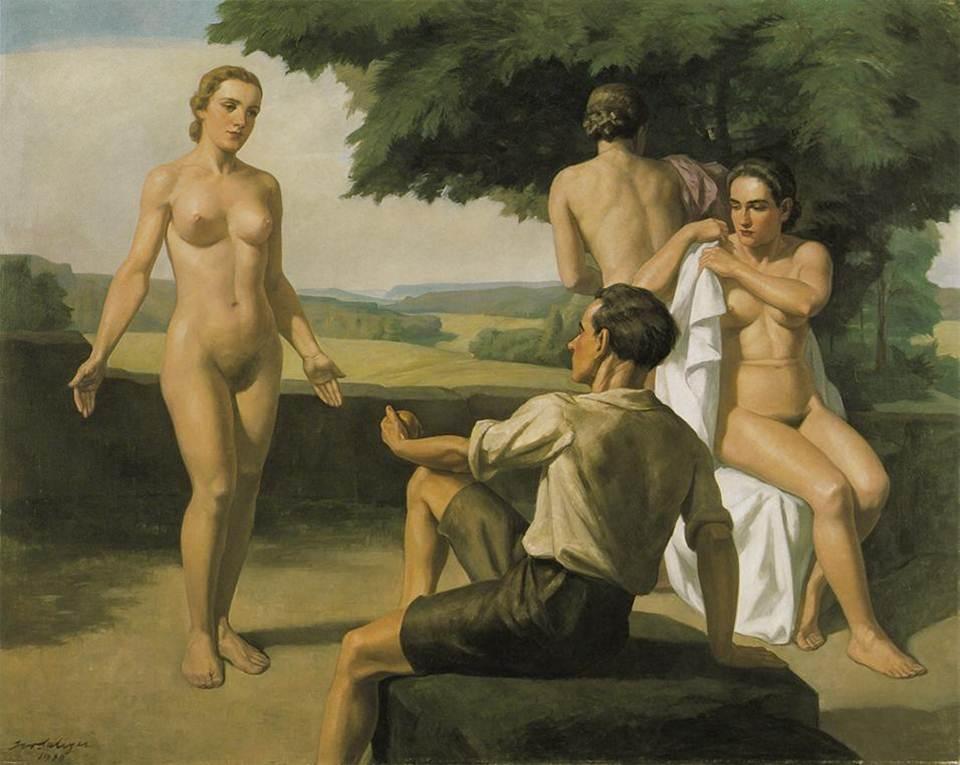

[IMAGE: Ivo Saliger The Judgement of Paris 1939]