Nostalgia for Intimacy (Wellington: Adam Art Gallery, 2012).

It is often said that New Zealand art has been shaped by distance, isolation, and smallness. Twenty years ago, when I was curating the exhibition Headlands: Thinking through New Zealand Art1 with the Australian curator Bernice Murphy, she would link these ideas by speaking of the ‘intimacy’ of New Zealand art. In choosing this word, she implied that we had an intense, inwardly focussed scene in which the proximity of competing claims was especially keenly felt. However, when she first said it, I didn’t get it. Back then, I didn’t see New Zealand art as particularly or unusually intimate. Now, I realise that this was because I operated within the intimacy and took it for granted, whereas she came to it from outside, from a less intimate scene. Murphy’s idea grew on me. I think it explains a lot. At least, it explains a lot about New Zealand art’s past, rather than its present or future. It seems to me that New Zealand art has evolved from being a very intimate (enclosed, inward-looking) discourse to being a not-so-intimate (porous, outward-looking) one, and that we can’t really understand it without taking this transformation into account.

Intimacy is a double-edged sword. It can be nice and cosy: you know everyone and have the measure of them, they are family. But it can also be frustrating and oppressive: others press up against you, they cramp your style, they compete with you for resources and airtime, everything gets personal. Intimacy can encourage close reading and passionate debate, but also blindness, fiefdoms, and feuding. It can open eyes and it can close them. You might ask: why is it even necessary to talk about intimacy, which is a vague idea, when distance, isolation, and smallness are simpler, clearer, more concrete ones? I’m drawn to the intimacy idea because it is about the way these external factors have been internalised—psychologised.

•

I

In the early days, the New Zealand art scene was relatively small, provincial, and enclosed. New Zealand art was largely made in New Zealand, by New Zealand artists, for New Zealand audiences. It was shown in New Zealand galleries, bought by New Zealand collectors and museums, and written up in New Zealand journals by New Zealand critics. It was called ‘New Zealand art’ and sometimes it was about New Zealand. Influences came from outside—New Zealand art was repeatedly seeded from elsewhere—but those influences took root and developed here in often eccentric ways. Further, the art made here largely stayed put, failing to escape our shores to seed discussions elsewhere. In his essay ‘Infectious Rhythms’, Nigel Clark calls this condition a ‘logic of islands’.2

In the 1970s and 1980s, New Zealand’s art discourse was organised around an antagonism between nationalism and internationalism. At their extreme, nationalists may have had an idea of art fetishistically grounded in New-Zealand-ness, but, more generally, they simply assumed, or preferred, an inwardly focussed, self-determining scene. By contrast, the internationalists wanted New Zealand art to be part of a wider ‘international’ discourse, engaged with what was happening in ‘the centres’ (London, New York, etcetera). That said, internationalism could mean very different things. Emerging in the 1970s, the internationalist critic Wystan Curnow supported abstraction and post-object art.

However, another internationalist critic, Francis Pound, who emerged in the early 1980s, ignored the post-object, concentrating on the painting mainstream.3 As outward looking as it sought to be, ‘internationalism’ was part of the local discourse: internationalists lobbied for particular practices within New Zealand art. The nationalism/internationalism debate was artistic, but it was also art-political. It was about who would control the discourse, on what basis, and to what end. It was about degrees, forms, and shapes of intimacy. It was about managing intimacy.

In 1973, in his essay ‘High Culture in a Small Province’, Wystan Curnow argued that the thinness of New Zealand’s high culture was the cause and effect of a ‘lack of psychic insulation’ (a.k.a. excessive intimacy).4 He characterised the art scene as a pyramid. At the top, where the air is thin, are a few artists posing and answering the big questions. Below them are mediators, cultural middle men, such as curators, critics, and university lecturers. They broker the artists’ work to the biggest group, the broad base of the pyramid, the public for art. Curnow argued that the work of those at the top will simply never be understood by the great unwashed. He said, in a functioning high culture, the middle men see it as their job to insulate the artists from the public by generating cultural clout, a climate of legitimacy for art, so that art is valued even if it isn’t understood. By doing this, they seek to increase the distance between the artists and the public, allowing artists to be ambitious, audacious, and extreme; allowing them to get on with the business of problem identification and solving. However, in a small culture like New Zealand’s, the middle men see it as their job to reduce the distance between art and its audience, to bring art down. They leave the artist exposed, making the job harder. Bad intimacy!

As much as Curnow saw ‘lack of psychic insulation’ as an impediment, it was a key to Colin McCahon’s success. The quintessential big fish in a small pond, McCahon had a complex relationship to intimacy. On the one hand, he was insulated—the ultimate insider. He was always championed and protected by friends in high places. In the early days, it was the poets, the Landfall people; later, it would be the new specialist art professionals: art-museum directors, curators, and critics. From 1954 to 1964—a crucial time in the invention of New Zealand art—McCahon worked for Auckland City Art Gallery, under Eric Westbrook then Peter Tomory, starting as a cleaner, ending up as a curator. That experience would inform his art practice, and his practice would inform the emerging idea of New Zealand art that the Gallery was forming and promoting. On the other hand, McCahon was also exposed. He felt the culture pressing upon him. It’s often said that he had a fraught relation to his audience, stewing over public response, even changing direction when he felt he had built a bridge too far and had left the audience behind. And yet this anxiety was underpinned by what, to me, seems an extraordinary assumption: that the public was his public and should understand him; that he might, indeed, be making ‘signs and symbols for people to live by’.5 While McCahon was poked and picked at, he was also hailed, not just as an artist, but as some kind of spiritual leader. James Mack described him as: ‘a great oracle and visionary … our personal communicant’.6

If the culture pressed on McCahon, he also pressed upon it. Curnow famously wrote of McCahon, ‘Having invented painting in New Zealand, he could now work in a tradition of his own making.’7 Of course, other artists had to work in that tradition too. During the 1970s—when he was at the height of his powers—McCahon represented an impasse for a generation of New Zealand artists. Everywhere they went, he seemed to have been there already. He could seem to occupy almost any position, depending on which aspect of his complex oeuvre you cared to emphasise. He was a nationalist and an internationalist; he was a primitive, a modernist, and, ultimately, a postmodernist; he was a landscape painter, an abstractionist, a conceptual artist, an installation artist. If he started as a white man laying claim to a silent land, he went on to embrace things Maori. He was believer and disbeliever, death-of-god theologian and passionate agnostic, prophet and heretic, optimist and pessimist. He could mirror anyone’s interests and anxieties. In McCahon, it seemed, you could find a precedent for almost anything that had or could happen in New Zealand art. Any image of a hill, a headland, or a black singlet, or any work about darkness-andlight or with text in it—they all seemed to nod to McCahon. His koru held hands with Walters and Schoon and his painted corners with Mrkusich. Hotere seemed especially endebted. McCahon’s use of raw unstretched canvases seemed to inform artists as diverse as Don Driver, Don Peebles, Allen Maddox, Philippa Blair, Tony Fomison, and Philip Clairmont, while his use of enamel house paints reached out to popists like Dick Frizzell and Paul Hartigan, etcetera. McCahon’s presence was unavoidable: godlike, immanent. For years, we assumed that he was our calling card, New Zealand art’s best chance of getting a gig offshore. Younger artists must have felt they were queuing behind him.

When McCahon started, there was no scene. By the time he died, in 1987, there was, and he was a household name. McCahon had always been influential on other artists, helping define whole idioms of New Zealand art, but, after his death, there was an epidemic of McCahon quoting. It took a range of forms, drawing on diverse aspects of McCahon’s oeuvre. The quoters would include the likes of Julian Dashper, John Reynolds, Michael Parekowhai, et al., Ronnie van Hout, Ian Scott, Stephen Bambury, Peter Robinson, and Shane Cotton, not to forget Imants Tillers and other Australians. Looking back on all this work, it seems that some quoters wanted to borrow McCahon’s gravitas, some wanted to mock it and its claim to Capital-T truth, but many were undecided, even conflicted. This confusion was neatly expressed in the vacillations and ambivalence of Tina Barton’s prescient 1989 exhibition After McCahon at Auckland City Art Gallery.

In the 1970s, when artists quoted canonical figures, it was largely understood as influence or homage. But, by the post-modern late-1980s, quotation was ‘appropriation’. You repeated things, not to identify with them, but to express your ‘differance’. And, as much as this new work quoted McCahon, it did not share in his project. It was a fundamentally different kind of art. And that was the point. The overabundance of McCahon signifiers in art of the late 1980s and 1990s actually pointed to the impossibility of being a McCahon now. Those citations were a response to an intimacy vacuum caused by McCahon’s demise, his ultimate passage into history—the fact that now you definitely weren’t going to bump into him at an opening. Times had changed.

•

II

A new self-consciousness about intimacy came with Billy Apple’s second New Zealand tour in 1979–80.

In 1959, as a young man, Apple had escaped our shores to study at London’s Royal College of Art, where he would be part of a cohort that would define a new phase in British pop art. Later, he decamped to New York, and made conceptual art. In 1974, he enjoyed a retrospective at London’s Serpentine Gallery. When he came home to New Zealand to visit his parents in 1975, he was well ahead of the game here. During his visit, Apple made a series of conceptual art exhibitions in museums and galleries throughout the country. These projects addressed gallery spaces, typically ‘subtracting’ things from them—for instance, wax from a square of floor tiles. New Zealand wasn’t ready for Apple’s esoteric avant-gardism. The media had a field day. There was a bad-press barrage.

In 1979, Apple returned again, better prepared and better resourced. Again, he made shows on the hoof, responding to spaces across the length of the country. This time critic Wystan Curnow rode shotgun, offering himself as a middle man to manage the media, to provide psychic insulation. Titled The Given as an Art-Political Statement, the works Apple produced showed what was already there. He put the exhibition spaces themselves on display, highlighting their quirks and inadequacies as symptoms of deeper philosophical and political issues, and suggesting improvements. Coming in like an architectural editor, with a big red pen, he prompted gallerists to get their acts together and told them precisely how to do so. He made back-of-house matters, not normally part of the public art discussion, stand out like sore thumbs. His provocations raised questions of how much the spaces actually worked for artists and their audiences.

Not only did Apple address galleries and gallerists specifically (naming names), he implicated numerous artists and artworkers in executing and documenting the shows. For instance, at Barry Lett Galleries, Auckland, he was assisted by artists John Bailey, Ian Bergquist, Robert Ellis, and Peter Hannken; at Brooke-Gifford Gallery, Christchurch, by artists John Hurrell, Paul Johns, and Glenn Jowitt; and at Bosshard Galleries, Dunedin, by artists Jeffrey Harris, Ralph Hotere, Clive Humphreys, and Russell Moses. It was like a who’s-who of the scene. When Wystan Curnow filed his ‘Report’ on The Given in Art New Zealand, they started his text on the cover, as if it was front-page news. They even let Apple design the cover. Apple was like a virus. He was everywhere. The Given mapped the New Zealand art world, and made its human cogs consider their relationships with one another. It exposed their intimacies. Elsewhere, Apple made works in The Given series, but they would not achieve the purchase and saturation that they did in New Zealand. Apple couldn’t get his foot in enough doors in New York to do something similar there.

Apple’s art polarised people. It must have seemed presumptuous—his flying in from New York to tell us what was wrong with our galleries, exposing us to ourselves. Locals were bound to have mixed feelings towards him. But the anxiety around Apple was also tied to deeper art-scene issues. Thus far, New Zealand art had been dominated by the heart, but art of the heart was coming under pressure from abstraction, post-object art, and a nascent postmodernism—arts of the head. In New Zealand, Apple become symbolic of this change of guard, a shift in the idea of the artist. Indeed, he was a shibboleth: liking or disliking Apple was a mark of which side you were on.

One day, the heart/head conflict erupted in a most intimate manner in a private house: 29 Albany Road, Herne Bay, Auckland. It was the rented residence of hip art couple, new critic on the block, Francis Pound, who would soon publish his book Frames on the Land, and partner Sue Crockford, who would later open her agenda-setting internationalist dealer gallery. Apple, who had been staying at their place while they were away, suggested they develop their spare room as a gallery and offered to do the first show, proposing corrections to the room to bring it up to spec. Apple painted a manhole cover in the ceiling red, slating it for removal, and drew red lines on the wall, indicating where the window and architrave should be moved to. On 23 March 1982, Pound and Crockford invited friends and colleagues over to see the work, titled Private View: Declaration/Critique of the Given. The guests included artists, art dealers, and lecturers from the University of Auckland Art History Department. Among them was painter Pat Hanly.

Hanly was of the same generation as Apple. He had also left New Zealand for London in the late 1950s. However, his work had taken a different path, through expressionist painting. In 1962, he returned to New Zealand, en route to Australia, but, liking what he saw in Auckland, decided to stay. In 1964, his hard-edged Figures in Light series earned him a key place in the nationalist canon, and, in 1969, Gordon H. Brown and Hamish Keith granted him a whole chapter in their An Introduction to New Zealand Painting (it was the last monographic chapter in the book). In 1974, he had a retrospective. Hanly was celebrated as a joyful expressionist whose paintings captured the feel of the Pacific. New Zealand Who’s Who would later list his recreations as ‘kite-flying, sailing, Greenpeace’.8 On that evening, however, he became an art terrorist.

Taking umbrage at Apple’s brainy, tidy work, Hanly decided to protest on behalf of the heart. Part way through the soirée, Hanly went outside and found some paving paint and a brush. He returned and painted, freehand, two huge eye-in-heart tags—a signature motif, a personal expressionist manifesto—on two facing walls in the ‘gallery’, wrecking Apple’s show. A bit of necessary correction, Hanly’s own ‘critique of the given’, the return of Apple’s repressed, it caused a kerfuffle, and was too much intimacy for Apple, who left the building, preferring not to deal with Hanly, even as RKS Art’s Joan Livingstone entreated Apple to return and enter into a dialogue with him.9 Nowadays, it is hard to imagine a time when Billy Apple was considered such a threat to the future of art that a fellow artist would go to such lengths to attack his work in a private home; it is hard to imagine anyone caring that much.

The incident has an ambiguous status. One could regard it as trivial, a case of an artist behaving badly, something outside the discourse proper, or one could see it as evidence of a seismic shift in the New Zealand art scene. But, should it be seen as private or public? Should it be kept private or made public? Later that year, Pound wrote a piece on Apple for Auckland’s Metro magazine.10 He was initially going to discuss the incident, but thought better of it, and cut the passage from his article. In the early 1990s, Apple pitched Attack on the White Cube, a pagework about the incident, to Midwest magazine, where I was co-editor. It contained the passage Pound had excised from his Metro article. His eye-witness account—his affidavit—oscillated between descriptive neutrality (we learn the brush was two-inches thick and the paint was ferric red oxide) and barely concealed pique (he described Hanly’s tags as ‘banal symbols’). The proposed pagework also included polaroids of Hanly’s graffitos (submitted as evidence). We turned it down. It seemed mean-spirited. Indeed, at the time, it didn’t seem to be much of an artwork. Years later, however, I changed my mind, as I came to appreciate the significance of the incident, which, for me, had morphed from being a side issue to a central one. Not only does Attack offer a rare view of the scene as a site of bitter competition, a real typically papered over by press-releases and gallery wall texts, it also offers evidence of a decisive heart-to-head shift. In 2005, when I was contemporary art curator at Auckland Art Gallery, we acquired it for the collection.

•

III

In many ways, Julian Dashper is Billy Apple’s heir. He also exposed beside-the-point matters. He explored art’s overlooked supports, making art’s supplements, technicalities, and legends the crux of his practice, fetishising the businesses of promoting, presenting, and documenting art. Although much of his work looked abstract, Dashper rejected any suggestion that the artwork was autonomous. For him, the work was never a thing in itself; it was always part of a system.

In the late 1980s and early 1990s, Dashper seemed to be insinuating his way into New Zealand art history by creating works that referred to canonical figures, such as McCahon, Rita Angus, and Gordon Walters. However, Dashper seldom made reference to their works directly, preferring to deal instead with legends that surrounded them, often things only insiders, intimates, or trainspotters might know. Dashper’s homages were perverse, because, while apparently celebrating other artists, they always managed to sidestep the actual point of the artists’ works, their achievements. Dashper’s works drew on the intimacy of the New Zealand art scene. In this country, he could show in the same dealer galleries and museums as the canonical figures he referred to; indeed, some of those still living might even come to the opening. He could also assume his local audience was aware of and/or cared about trivial details in the back stories of the artists he referred to. While Dashper also made works that referred to international figures, like Edvard Munch, Barnett Newman, and Daniel Buren, these references would never resonate socially as much, in New Zealand or anywhere else.

It says something of the intimacy of the New Zealand scene that our art museums—those guardians of the flame—would let Dashper hang his works alongside works by prominent New Zealand artists in the most perverse ways. For instance, in 1990, Hamilton’s Centre for Contemporary Art let Dashper contrive a bizarre conversation between himself and expressionist hero Philip Clairmont, who had died by his own hand in 1984. Alongside Clairmont’s Staircase Night Triptych (1978) and Mark Adams’s photo-sequence of him painting it,11 Dashper hung an affectless, generic abstract he had made for the occasion with an Adams photo-sequence of Dashper painting it. Adams’s photos of Clairmont belong to a tradition of photographers catching expressionist heroes in moments of genuine creativity, but Dashper’s cool ironic art was just the opposite. Rather than suggest an affinity between the two artists, the juxtaposition emphasised a gulf. (In the catalogue, Dashper listed banal things he supposedly remembered Clairmont saying, things we wouldn’t expect from an expressionist hero who sucked the marrow from the bones of life. Things like: ‘Do you like my new sports jacket?’) Clairmont would have turned in his grave.

In 1992, when he presented Julian Dashper’s Greatest Hits at New Plymouth’s Govett-Brewster Art Gallery, Dashper explored intimacy in a new way, upping the ante by incorporating the physical person of another artist into his work. Greatest Hits included Dashper’s installation The Drivers, which referred to a major local artist, Don Driver. Driver was strongly identified with the Gallery and the city. His work had always been a staple of the Govett-Brewster’s exhibition programme and was well represented in the collection. Driver had also worked at the Gallery continuously since 1969 in various capacities, including a stint as Acting Director. However, by 1992, he was working as a gallery attendant. Dashper installed The Drivers in the two rooms on the ground floor. In one room, he placed a drum kit bearing the title ‘The Drivers’; in the other, he installed a window in a wall, providing a view into the collection-storage area.

This view—which featured two iconic Drivers, Flyaway (1966–9), from the Govett-Brewster collection, and Red Lady (circa 1968)—was artfully arranged, as if set up for a photo shoot. Indeed, it recalled Marti Friedlander’s iconic photos of Driver in the Govett-Brewster basement (in which Flyaway and Red Lady had also appeared) from Jim and Mary Barr’s 1980 coffee-table book Contemporary New Zealand Painters A–M. For those unfamiliar with the book, Dashper left two copies opened at relevant pages in a display case.12

Poised between homage and sendup, The Drivers was site specific: the Gallery itself and Driver-on-duty-in-it were crucial components (aspects of what Apple had called ‘the given’). Experiencing the work was informed by knowing that its subject was right there, patrolling the gallery. This drew attention to the space between the celebrated Driver, name artist, collected by the Gallery, and represented as a younger man in Friedlander’s photos, and the older, frailer Driver, there on the gallery floor, a customer-services officer. (Perhaps these two different Drivers were what was suggested by Dashper’s plural title.) With Driver there, your reading of the work was complicated by having to think about it through his eyes; considering how he related to it, how he felt about the liberties Dashper had taken with him and his work. One also had to think about the ethics of the Gallery (his employer) in allowing his works in its collection and him personally (as an employee) to be co-opted and put on show by Dashper in this manner. Dashper’s work played on the Gallery’s complex relationship with Driver, as simultaneously a lofty artist and a lowly employee. Indeed, while Dashper’s show was on, Driver lost his job at the Gallery, having worked there for over twenty years. In 1999, the Gallery toured With Spirit, a retrospective of Driver’s work.

•

IV

In the same year that Dashper made The Drivers, 1992, Driver and Dashper both featured in Headlands.13 The show was all about intimacy.

For my co-curator, Bernice Murphy, Headlands was a reply to—and critique of—the 1988 exhibition NZ XI, at Sydney’s Art Gallery of New South Wales. Curated by Francis Pound, the Art Gallery of New South Wales’s William Wright, and Auckland City Art Gallery’s Alexa Johnston, NZ XI promoted an idea of export-quality, export-type New Zealand art. It showcased eleven artists that the curators thought could stand on their own offshore, whose art was not excessively dependent on local contexts and backstories.14 However, what was seen as international in 1988 seems surprising in retrospect. Denis O’Connor was an oddly crafty pick, and Christine Hellyar a rustic one. Back then, Jeffrey Harris seemed less expressionist, more David-Salle-esque, while Maria Olsen was being compared with Anselm Kiefer and Philip Guston. Crucially, the show included expatriate artists Bill Culbert and Boyd Webb, both of whom had been living outside New Zealand for more or less their entire careers. Above all, NZ XI enshrined Richard Killeen, who Pound had been championing as post-modernist and wielding as a stick to beat the nationalists. More than half the artists were represented by Crockford. The exhibition title suggested that this was a national representative team, the country’s top players, although perhaps not those of the nationally preferred game, in which case it would surely have been ‘NZ XV’. The show was national, not nationalist.

Bernice Murphy was critical of shows like NZ XI for sidestepping the local discourses in which artists’ practices were embedded. She saw their ‘internationalism’ as slavishly provincial and homogenising. Instead, she wanted Headlands to offer a thicker, more locally-specific account of New Zealand art. While including nationalists and internationalists, we set out to demonstrate that both were implicated in an intimate local discussion. We presented works as commenting on and picking fights with one another. We wanted to show ‘New Zealand art’ as contested ground. Partly Headlands was archaeological (about disclosing real positions in the history of the discourse), partly a wilful new build (perversely opposing works to prompt new readings).

Headlands juxtaposed artists in ways that some people considered inappropriate, even shocking. For instance, we put a sublime Milan Mrkusich corner painting next to a trash sculpture by Don Driver that mocked the idea of transcendence, and a Sandy Adsett kowhaiwhai next to a Gordon Walters koru painting.15 We put top-shelf ‘export’ artists alongside neglected figures like Michael Illingworth and Dennis Knight Turner, and integrated Maori and Pakeha artists (something new at the time). This argumentative approach was carried over into the catalogue, where we commissioned critics and historians to write opinionated pieces on themes in New Zealand art. One essayist, the young Maori curator Rangi Panoho, slated Walters for his appropriation of Maori motifs (his argument, it must be said, already had precedent in recent local debates).16

Headlands was well received and favourably reviewed by the Australians. However, at home, it was criticised for its flippant approach in general and for Panoho’s—and by extension the curators’—lack of deference to Walters in particular. Underpinning this, I think, was a concern, in certain quarters, that the project had not centralised Killeen and endorsed NZ XI’s ‘export-quality’ canon and internationalist ethos. Letters of complaint and responses to them rolled out over fax machines, and were copied to all and sundry (we didn’t have the Internet then). The charge was lead by Laurence Simmons (a critic and key Killeen supporter), Killeen (who was in both NZ XI and Headlands), and Pound (a NZ XI curator, a Headlands essayist, Killeen’s critical champion and collaborator, and partner of his dealer). This interest group argued that the show was an insult to the culture in general. Killeen wrote: ‘The great works in this exhibition should be presented as icons from our culture that we are proud of … What went wrong?’17 Simmons wrote: ‘It must be a curious feature of the “cultural cringe” in New Zealand that we send work by major cultural practitioners to represent us overseas only then to rip them to shreds “out of context” rather than present some form of united front.’18 (That seemed an odd argument from someone who was themselves ripping the show to shreds, rather than supporting it as part of a ‘united front’.)

Pound and Killeen also wrote to my boss, Govett-Brewster Art Gallery Director John McCormack (also on the Headlands curatorium), rescinding an offer to let us stage a Killeen exhibition. They wrote: ‘We cannot work with and nor can we seem to give support to Robert Leonard. He completely lacks any sense of the proprieties of public exhibitions.’19 But what did they mean by ‘the proprieties of public exhibitions’? Basically, they saw Headlands as exhibiting New Zealand art’s dirty laundry, revealing local issues to outsiders, exposing our intimacy.20 In some ways, that seemed an odd position for them as internationalists to adopt. It was certainly a mark of how isolated New Zealand art still was, even in 1992. The embarrassment that resulted when our art didn’t present an appropriately scrubbed face (a ‘united front’) offshore highlighted the perception of a divide between local (private) and international (public).

Admittedly, there was nothing saintly about Headlands. There was a naughty factor in the selection and juxtaposition of artists. And, while we intended to annoy people, I’m still surprised quite how much we angered them and how much institutions would subsequently close ranks to silence the show. Not only should our dirty laundry never have been shown in public, it seemed that, having been shown in public, it should now not be shown in private (back home). Headlands involved substantial national investment, and, even if it only travelled around the corner to Sydney, it was, and remains, the largest ever export show of contemporary New Zealand art. However, it became the show New Zealand institutions didn’t want you to see. Two of the three New Zealand main-centre venues pulled out, scuttling a tour. Auckland Art Gallery had issues: they rightly saw Headlands as critical of their NZ XI, plus they were lobbied. They put on a Magnum photography show instead.21 Dunedin cancelled, even though its Director, Cheryll Sotheran, had been on the curatorium. In Wellington, Headlands had an eight-week run at the Museum of New Zealand (the co-organising gallery), with no opening (instead ‘a forum’) and scant promotion. There, it was a casualty of in-house politics, being identified with the National Art Gallery’s former Luit Bieringa administration, and thus not part of the brave new world that would be Te Papa. Although, actually, Te Papa and Headlands had much in common.

John Daly-Peoples would write: ‘Headlands will be reviled, revisited, reinterpreted and reassessed but ultimately it will be the significant exhibition of the ’nineties having marked out points of reference for the next decade.’22 However, at home, the show’s influence mostly came via professional insiders who went to Sydney to see it, and through the catalogue. I bring up Headlands not to wax lyrical about an aspect of my own history or to stir up stuff that has, mercifully, long since settled. It’s twenty years ago now—water under the bridge. Rather, I bring it up because Headlands and the response to it say a lot about the intimacy of New Zealand art and about unstated expectations about how that intimacy would be navigated and managed at that particular transitional moment. Certainly, it is hard to imagine an exhibition of New Zealand art being put together in this way again, or one causing that much wrath and pontificating. It says a lot that the next export show of New Zealand art—one more in the vein of NZ XI—would be titled Cultural Safety (1995).

•

V

In my notebook, I’m always making lists of works for potential exhibitions. I have one for a show on intimacy in New Zealand art called Love Thy Neighbour. In addition to Apple’s Attack, it includes all sorts of things …

In the late 1980s, Gavin Chilcott received a ‘dear John’ letter from his Wellington dealer Peter McLeavey, informing him that he had been excised from the stable. Chilcott made a series of drawings obsessively reproducing the kiss-off letter, as if needing to process his feelings about it. Dashper did something similar when he made his artist book Reviews in 2002, anthologising all the snippy notices he’d received at the hands of Herald critic T.J. McNamara. Its dedication: ‘He loves me not.’

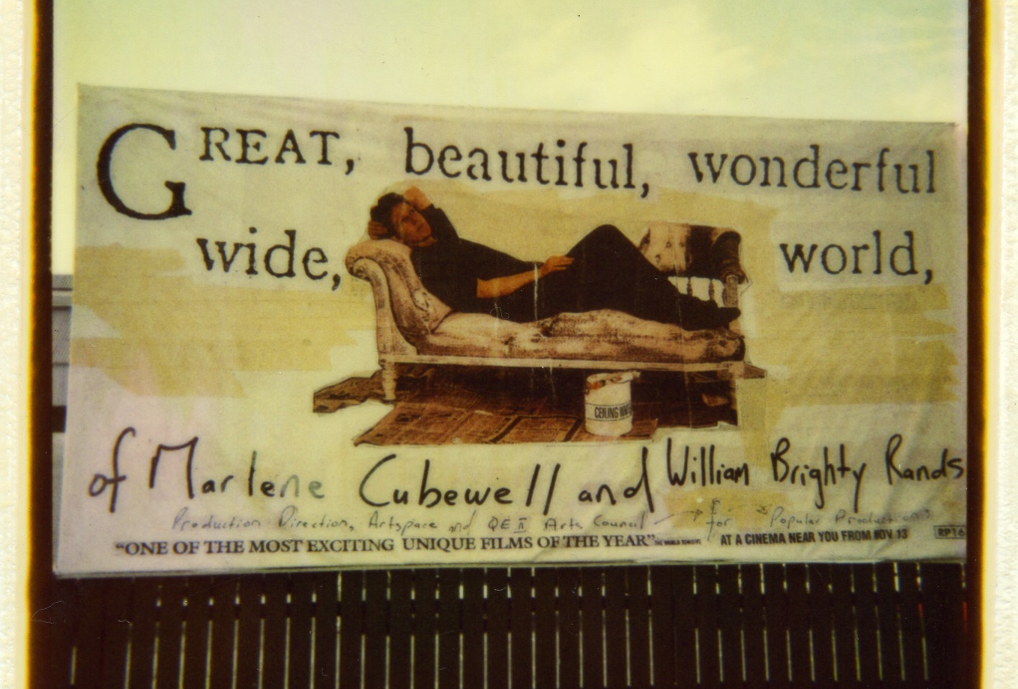

In 1992, et al. was installing a show at McLeavey’s. Unsupervised, she went too far, ‘blonding’ his beloved signature chaise longue with her own signature white paint. The show closed before it opened, the artist’s stuff was trucked back to Auckland, and the chaise sent off for repair. As if proud of what she had done, in 1993, as part of the Changing Signs project, et al. installed a huge public billboard of herself reclining on the blonded chaise behind a pail of ‘ceiling white’. It included the text ‘One of the most exciting unique films of the year’, as if to say, ‘take that Peter McLeavey’. At some point, the paradoxically publicity-averse artist blacked-out her image—to protect her own privacy! Not that the hundreds-of-thousands that drove past each day would get any of it, or care. It was the most outrageously private kind of public art. Thank you QE2.

Intimacy can be a matter of rancour, but it can also be the realm of sloppy kisses you don’t want and didn’t ask for. In 1991, Julian Dashper and John Reynolds hand-wrote a cloying two-page love letter to Sir Toss Woollaston, and published it as a pagework in the Listener.23 (How they managed to convince the mass-circulation TV guide to publish this in-joke, I’ll never know.) In 1997, Daniel Malone also got too close. Learning that the brand-obsessed Billy Apple had never officially changed his name, Malone changed his own name to Billy Apple by deed poll, creating a situation where there could be two ‘Billy Apples’ in the same room.

In 1994–5, Julian Dashper’s partner, Marie Shannon, made photographs of texts supposedly recounting his dreams. In one, a gallery-goer ‘accidentally’ spills a pink yogurt drink onto a terracotta-and-blue Mrkusich Journey painting. In another, Dick Frizzell gets a retrospective, but it’s in Fiji. In 2006, Tessa Laird expanded on this idea, producing Nights of Our Lives, a soap-opera anthology of artists’ dreams, most of which involve friends and foes from the New Zealand art world.24 In one contributor’s dream, I marry a Tibetan shaman and we set up a gallery in Mount Albert to sell our own work. If dreams express disavowed desires, the opposite would have to be P.S. I Love You (2001). Pervert Terry Urbahn made a stalker video of City Gallery Director Paula Savage, and presented it in her gallery in a group exhibition appropriately titled Prospect. He filmed Savage from behind bushes. From a slow-moving car, he recorded her sashaying down Oriental Parade. Was she flattered or creeped out? I was certainly creeped out when Terrence Handscomb published his art-world sexual wish lists and black lists in Log Illustrated in 2000.25 I was on the lists of those he wouldn’t sleep with for aesthetic reasons but, curiously, also of those he would have liked to sleep with if he were a lesbian. In this piece, Handscomb also outed a potential conflict-of-interest couple that no one was supposed to know about, although we all did.

Handscomb’s list was published after he had decamped to Berlin, where he didn’t have to deal with the intimacy fallout. The following year, also in Berlin, Michael Stevenson unveiled Call Me Immendorff. The project addressed the way the Auckland village had responded to the visit of the priapic world art star Jorg Immendorff back in 1987–8—bling, babes, death threats, and all. Stevenson superimposed our intimate cow-town micro-politics onto serious global macro-politics—the stock-market crash and the fall of the Berlin Wall. Finally, following Dashper’s lead, Dane Mitchell became notorious for playing institutional-critique-type pranks upon gallerists. For instance, in 2000, at Auckland’s rm212, he displayed revealing items gleaned from Gow Langsford Gallery’s rubbish. When he received a lengthy cease-and-desist letter from the lawyers, he showed it instead.

None of these works address intimacy directly. But in doing other things—mostly niggling the neighbours, forging generation gaps, and marking territory—they made it their subtext, and in very nuanced ways. Significantly, all these works were produced at a time when intimacy was disappearing, when our art world was expanding and beginning to open up, when we could begin to imagine things differently, when we suddenly had distance on closeness. This brings me back to Julian Dashper.

•

VI

It seems to me that Dashper bridged a transition, as New Zealand art moved from being an enclosed discourse to an open one. His work marks, explores, and participates in this transition. As much as he was obsessed with the details of local art history, Dashper always aspired to be part of the wider, international discussion. While his earlier work was keyed to the New Zealand scene, exploiting its peculiar insularity and intimacy, from the mid-1990s on his focus was outside New Zealand, in seeking to become an international artist (not an internationalist artist within New Zealand, but an artist ‘in play’ overseas). To become an international artist, he changed the shape of his project. He jettisoned New Zealand references and themes, producing works that could travel, physically and philosophically. But I don’t think he ever really got rid of intimacy issues.

In 1997, Dashper made a show where he actually used the word ‘intimacy’. At Auckland’s Teststrip, Dashper exhibited his burgeoning CV as an artwork. This list of his exhibitions and publications, his professional pedigree, could be seen as an index of intimacy, a guide to all the art-world encounters, connections, and relationships that had brought him to this point. And, by 1997, Dashper’s CV certainly tracked his moves to position himself as international. The turn of the screw, however, came with the second part of the show—the invitation card. Invitation cards are important in the artworld, being posted to insiders to shoulder-tap them to attend openings, to lend their cultural capital to the gallery, the artist, and the show. Invitations often carry the line: ‘the artist will be present’. However, on Dashper’s card was written: ‘There will be no formal opening for this exhibition. Instead, the artist has a request. Despite the fact that your presence will not be required … Julian Dashper nevertheless asks that you commit the hour from 6pm to 7pm on Wednesday 19th March, when you would otherwise have been attending the opening, to a specific undertaking. You are requested to spend this time in the pursuit of intimacy. Please choose a close friend or loved one, and, for this hour, dedicate yourself to developing with them a deeper level of communication, vulnerability, openness, and conscious nurturing of the relationship. Thank you.’

Dashper’s show was about mixed messages. On the one hand, his CV exhibit was like one of those affectless shows that successful artists arrogantly phone in, and don’t even bother to turn up for, taking them as little more than an opportunity to parade and extend their CV—they have bigger fish to fry. On the other hand, Dashper’s rejection of intimacy (no party) was also a call to intimacy (to stay at home, haul out the candles and essential oils, and spin some Barry White). Was this rudeness framed as generosity, or generosity framed as rudeness? I imagine many targeted recipients would be disgusted by the thought of ‘developing … a deeper level of communication, vulnerability, openness, and nurturing’. It is not something we necessarily want to do. Indeed, after work, we go to openings to avoid going home. With his confusing instruction, Dashper crashed all manner of artworld intimacy frames, while playing on his newfound status within the local community as an offshore player, a frequent flyer—an intimacy escapee.26

•

VII

When Dashper started shifting offshore, it was a hard row for him to hoe. By contrast, a subsequent generation of New Zealand artists and curators would take international engagement for granted. So, Dashper straddles a paradigm shift. If we stress the first act of his career, we find him engaged with old-school New Zealand art (hanging onto the past), making the intimacy of New Zealand art his subject. But, if we stress his second act, we see him turning his back on it. Consequently, we can understand Dashper as ‘the last New Zealand artist’ or as the first of a new generation of New Zealand artists operating internationally in a post-medium, postnational art world. Today, we are in a phase I like to call ‘the end of New Zealand art’. The scene has grown and diversified—we have five art schools in Auckland alone. The world is smaller and larger: artists travel more and more widely; they have swift access to information; they operate within a larger, more global art world. Following the 1997 New Vision report, we routinely send artists to offshore residencies and to Venice. These days, we expect artists to come and go; indeed, of the eight artists we have chosen for Venice, five were already living in Europe. Our curators find work overseas (Sydney, Toronto, Dublin, Vilnius, and Vienna), and our galleries recruit curators from overseas. In the academy, performance-based research funding stresses overseas outcomes, for quality assurance; local shows barely figure.

Today, our artists and curators are looking outwards rather than inwards, finding the stakes for their work in discussions elsewhere. We now have internationalism at all levels; it is assumed. The idea of ‘New Zealand art’ no longer has much purchase on the way we produce and read the art currently being made by New Zealand artists.

It’s true that some aspects of New Zealand art remain stubbornly local, particularly the market. Local-hero artists like Bill Hammond have achieved spectacular prices domestically, while lacking any real market offshore, and some museums persist in presenting new New Zealand art as if it were a thing apart, although mixing it up is increasingly common. Our museums still collect local art comprehensively, and other art barely at all, and are clearly finding it hard to change gear. But, when you look at what’s showing in the dealers and art spaces, and what artists and particularly art students are looking at and doing, it’s clear that there has been a massive shift. Increasingly, the New Zealand art canon seems irrelevant—not worth fighting for, against, or over.

Obviously, on an immediate and individual level, intimacy will never go away. There will always be struggles, antipathies, and resentments—other people will always be hell. However, intimacy is no longer a defining or distinguishing condition of New Zealand art. The internationalists got what they wanted. We are now part of the wider art world. Our problem now is that that world is so huge we are completely swamped by it—our efforts dissipated. Our artists and curators face a new set of problems.

While not all aspects of intimacy are good, these days I catch myself looking back fondly on earlier times, when New Zealand art was a more intensely local discussion, when New Zealand artists positioned themselves in relation to other New Zealand artists, when the proximity of other positions and competing claims seemed more urgent and consequential. I look back to a time of sandpit politics and storms in teacups, when people were at one another’s throats and in one another’s faces, and so much seemed to be at stake.

Bertolt Brecht famously railed against nostalgia, saying we should go for the bad new things rather than the good old ones—the bad new things indicate the directions in which culture is moving. I can’t deny that my nostalgia for intimacy stems from my being part of the Dashper generation, which was informed by the intimacy of New Zealand art while also wanting to escape it. But, I also wonder if that nostalgia might actually be one of the bad new things, because it is something I can only now feel, and, because, by sheer contrast, it illuminates our new cosmopolitan moment and terms of reference.

- Headlands: Thinking through New Zealand Art, Museum of Contemporary Art, Sydney, 1992.

- Nigel Clark, ‘Infectious Rhythms’, in Bright Paradise: The First Auckland Triennial, ed. Allan Smith (Auckland: Auckland Art Gallery, 2001), 25.

- In retrospect, we can see how, in the 1970s and 1980s, other domains—Maori modernism, the women’s art movement, and photography—were also heavily informed by overseas art developments, and were up with the play internationally in their own ways, even if they weren’t part of ‘internationalist’ arguments as they stood.

- Wystan Curnow, ‘High Culture in a Small Province’, in Essays on New Zealand Literature, ed. Wystan Curnow (Auckland, Heinemann, 1973), 155–71.

- Colin McCahon: A Survey Exhibition (Auckland, Auckland City Art Gallery, 1972), 26.

- James Mack, ‘Colin McCahon: A Great Oracle’, New Zealand Listener, 21 March 1987: 30.

- Wystan Curnow, ‘Necessary Protection’, in McCahon’s ‘Necessary Protection’ (New Plymouth: Govett-Brewster Art Gallery, 1977), 4.

- According to Wikipedia, see http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Pat_Hanly.

- According to Apple.

- Francis Pound, ‘Billy Apple in Auckland’, Metro, November 1982: 123–8.

- ‘Philip Clairmont Paints a Triptych’, Art New Zealand, no. 11, Spring 1978: 38–41.

- Jim and Mary Barr, Contemporary New Zealand Painters: A–M (Martinborough: Alister Taylor, 1980).

- We were supported by a curatorium of John McCormack, Cheryll Sotheran, and Cliff Whiting. For me, Jim and Mary Barr were a sounding board throughout the process.

- As Auckland City Art Gallery Director Rodney Wilson said in the catalogue, NZ XI sought to show ‘the vitality, the sophistication, and the internationalism of New Zealand art’ suggesting a necessary link between vitality, sophistication, and internationalism. NZ XI (Auckland and Sydney: Auckland City Art Gallery and Art Gallery of New South Wales, 1988), 5.

- T hey seemed edgy at the time, but, since then, these kinds of discursive juxtapositions have become the norm, a default setting in New Zealand museum-collection hangs. At Te Papa, Walters and Killeen hang alongside Adsett without controversy.

- See, for instance, ‘Ngahuia Te Awekotuku in Conversation with Elizabeth Eastmond and Priscilla Pitts’, Antic, no. 1, June 1986: 44–55.

- Richard Killeen to Bernice Murphy, 22 April 1992.

- Laurence Simmons to Bernice Murphy, 16 April 1992.

- Francis Pound and Richard Killeen to John McCormack, n.d.

- Francis Pound was later quoted as saying: ‘It is hardly appropriate to wash our dirty linen abroad in a publicly funded NZ exhibition … We should not be reducing a major travelling exhibition to an occasion for local vendettas.’ Quoted in Louise Garrett, ‘Reading Headlands’, MA thesis, Victoria University of Wellington, 1997, 16ff.

- According to Tony Green in his ‘Report for the Art History Department on the Forum on Headlands’, unpublished, 1992.

- John Daly-Peoples, ‘Auckland’, Art New Zealand, no. 65, Summer 1992–3: 26.

- John Reynolds and Julian Dashper, ‘Dear Toss’, New Zealand Listener, 23 December 1991–January 1992: 60–1.

- Nights of Our Lives, ed. Tessa Laird (Auckland: rm/press, 2006).

- Terrence Handscomb, Log Illustrated, no. 9, 2000: 13.

- Dashper produced a variation on the invitation as an advertisement for his exhibition Midwestern Unlike You and Me (Sioux City Art Center, Sioux City, Iowa) in Artforum, September 2005.