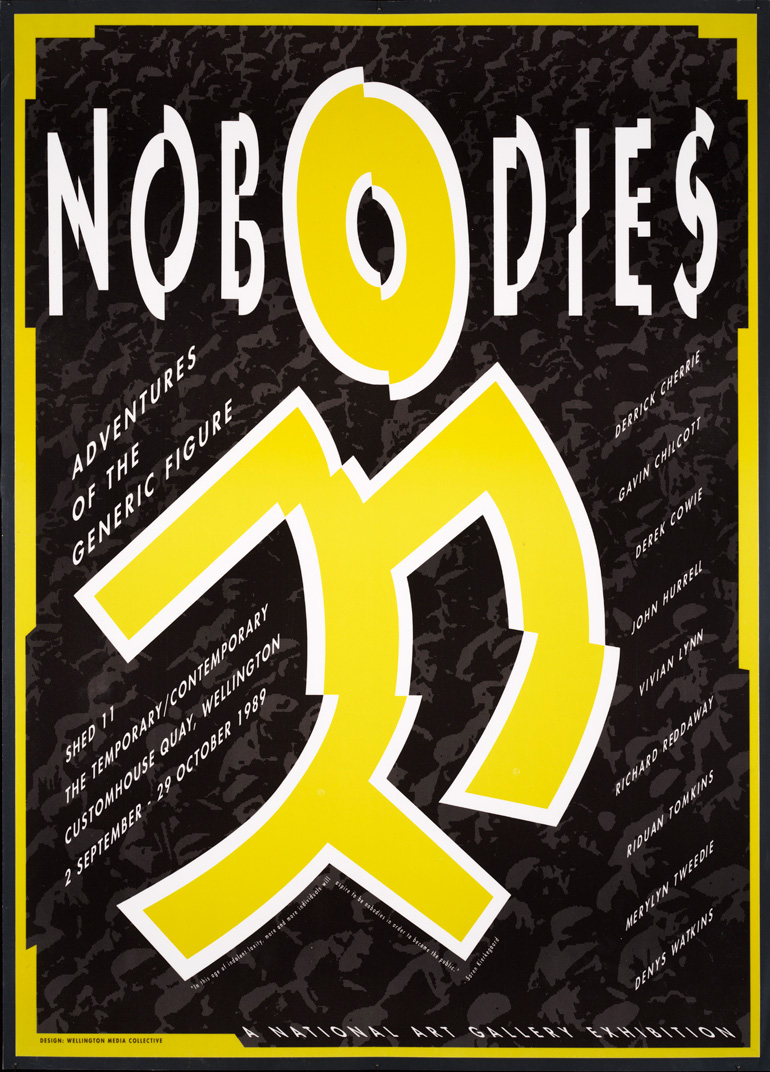

ex. cat. (Wellington: National Art Gallery, 1989).

Nobody is my name, I bear everybody’s blame.

—Joerg Schan, a barber of Strassburg, ca. 1507.

.

In this age of indolent laxity, more and more individuals will aspire to be nobodies in order to become the public.

—Soren Kierkegaard, Two Ages: The Age of Revolution and the Present Age: A Literary Review, 1846.

.

‘I see nobody on the road’, said Alice. ‘I only wish had such eyes’, the King remarked in a fretful tone. ‘To be able to see Nobody! And at that distance too! Why, it’s as much as I can do to see real people, by this light!’

—Lewis Carroll, Alice in Wonderland, 1865.

.

Homo-Generic

The subject of this exhibition is the generic figure—the human figure stripped of individuality, a figure peculiar for its lack of peculiarities. This non-entity crops up whenever a schematic, abbreviated rendering of the body is attempted, whether for the sake of speed, ease of replication, or with a desire for generality of reference. We meet such figures on road signs and toilet doors, everywhere and anywhere. The generic figure is nobody—nobody in particular.

To call someone a ‘nobody’ is to say there is nothing distinctive about him, that he is a man without qualities. And yet, to be so undistinguished is rare, distinctive even. In Don Siegel’s 1956 film Invasion of the Body Snatchers, such a figure is found. Apparently dead, this body is fully grown, but uncanny in its lack of detail. There is no character in the face, no prints on the fingers. In short: no identity. This figure is distinctive for its lack of distinguishing marks. Who is he? Where did he come from? Nobody knows. And he’s not telling.

Some bodies are born nobodies, some work hard for the distinction, others have it foisted upon them. Why would anybody become a nobody? Many reasons. Some do it to hide their identity: the secret agent, the burglar with a stocking pulled over his face, Jason, Michael Myers. Others, such as Leonard Zelig, do it in the hope of losing their individual identity, merging with the crowd, or the regiment, becoming one with the social body, sacrificing their personal identity in order to adopt a collective one. Such has been the dream of utopias and the nightmare.

In our male-centric society, the male presumes to stand in for the whole species. We speak of ‘man’ and ‘mankind’. The human subject is generally referred to by the male pronoun. To use the female pronoun is to make a point. The woman is marked off as different. Man is the standard. There are female generic figures and male generic figures. You may have seen the generic couple on convenience doors, often accompanied by their sexless cohort, the generic cripple. The female’s difference is marked by an addition—a skirt. The female figure is simply the male figure with something added; it is the generic figure more detailed, less generic. The male generic figure is the generic generic figure.1

.

Square Pegs for Square Holes

In his propriety, the generic figure is often a conformist. In Derek Cowie’s Day Care (1979), for instance, we find a number of faceless figures evenly dotted across a field, isolated, seemingly mindful of one another’s impersonal space. Each is posed and dressed identically, except for their choice of colours, attesting to a range of fashion options within the uniform. This is a colourful image of efficiency, a portrait of isolation—a representation of individualism as the ideology of conformity.

In 1979, Cowie also produced lots of little drawings by stamping a schematic body over and over onto scraps of brown paper, forming patterns and arrangements. He called these his Populations drawings. The patterns, the spaces around the figures and the manner of their linkage, suggest different kinds of psychological and political relationships at work in the population. These works show human subjects as equal and identical units, the population reduced to a pattern; individuals, not individual, but identical, literally stamped out, like the old cliché of the subject being stamped out by ‘the system’. They are minions, nothinks, ciphers, statistics, neighbours, friends, relations.

.

Churning Them Out

The ‘system’ has been the subject of much of Vivian Lynn’s work. Her Playground series (1975), for instance, allegorises the idea of capitalism as a scenario in which people are systematically desexualised, dehumanised, exploited, and discarded.

In Playground I, III, and V, sickly, naked, hairless, undistinguishable adults ride see-saws, swings, and roundabouts. But, they don’t seem to be having much fun. In Playground II, similar figures are conveyed passively over an abyss to an invisible fate, or perhaps just more of the same.

In Playground VI, the wretches are put to work as cogs in a huge machine. This machine could be a torture chamber; its parts resemble treadmills, wheels, devices of the Inquisition. This machine is ‘the system’, relentlessly, inevitably exacting its price; a factory less for producing commodities than for producing and consuming human beings. The allegorical nature of the image is even clearer in the preliminary drawing, which shows four male supervisors (identified by annotations as ‘state’, ‘big business’, ’church’, and ’military’), supervising the proceedings. (This detail has been excluded from the final print.) In Playground VI, the figures are all male, but they lack genitals—have been desexed, gelded.

The Playground series is a remarkable work, but as a portrait of capitalist exploitation it is banal, less analytic than homiletic. This limitation may stem from the very desire to read society in terms of generics, with the system imposing its will on the people, as if they were two distinct things, as if the system were not the people.

.

Discipline and Punish

In Merylyn Tweedie’s series Fresh Ideas for Man the Masterpiece (1988), anonymous wee chaps are again grafted onto bits of machinery. The series was based on an antique health manual, Dr J.H. Kellogg’s Man the Masterpiece, or Plain Truths Told Plainly about Boyhood, Youth, and Manhood.2 Kellogg promoted clean and healthy living. A eugenicist and an entrepreneur in the field of dry cereals, he was a staunch critic of masturbation. In addition to useful tips on how to assist your son in efficient resistance to the craving, the manual, particularly its chapter ‘How to be strong’, contained numerous line drawings of little men, each revelling in a dose of P.T. or otherwise being put to the test.

In Fresh Ideas, Tweedie collaged xeroxes of these little guys into seas of discontinuous text, as is her typical procedure. Some of the figures are all cut up, dismembered. Some have been grafted onto or into tools, labour-saving utensils, ending up as hybrid machine-men, monstrous little masterpieces, parodies of the original figures’ anonymous perfection and propriety. If that wasn’t bad enough, several have had their faces twinked out or their heads knocked off, to further put the boot in.

The motive: to turn the tables, get vengeance, or at least catharsis. To perform a sadistic act on the image of man’s body. To do to those guys in representation the same violence that has been done to women, both in representation and in the flesh. For women have been cut up, stuck on machines, and had their faces eliminated. Not surprisingly many of the utensils that penetrate these boys-wonder hail from the kitchen.

Much of the text evokes the tone of the Orwellian physical-education instructor, issuing numbered commands, subjecting the body to total administration, discipline. Man’s voice has been turned back on him, taunting: ‘29. Arms horizontal, palms inward; swing right’; ‘7. toe rising and breathing, ten times. 8. Dumb-bells upward raising from shoulders, fifty’, ‘Bracket arms fixed to the wall’, ‘down the side and return four times. 6. Repeat with the left arm, keeping the right’, ‘19. Alternate each’. Other text nominates domestic devices, suggesting them as means of torture: ‘Electric or gas iron’, ‘A washing machine, if possible’, ‘vi. Mangle. vii. Combined washer and ringer. viii. Electric iron’, and, pointedly, ‘Scrubbers’. These words themselves pass over and through the figures, further obliterating them.

These works are oddly reminiscent of the fantastic machine in Franz Kafka’s story In the Penal Colony. The machine exacts punishment by exactly inscribing the sentence onto the body of the condemned man, tattooing the text deeper and deeper into the wayward flesh until it is corrected finally in death. During this excruciation the convict learns to read the justice of his sentence, learns to appreciate its coherency, its suitability, its aesthetic. The operation is lovingly supervised by a warden, whose affair with the machine has been long and intimate, but not so intimate as to have experienced the goodly cutting words of the keys and knives on his own person. Eventually, he does turn it on himself. His execution, however, is cruel and incoherent. Snippets, scraps, and garbled stutterings are stabbed into his back. Erased rather than inscribed, his death enacts the unconscious of the legal machinery and sentence he enforced on others. Analogously, Tweedie deranges the sentence men have passed on women—domesticity—and so discovers the mad violence inherent in this grammar.3

.

Body-Building

In Romanesque and Gothic churches, one finds figures carved across architectural supports, such as tympana, at regular intervals. Some of these places are so dense with figures they seem to be entirely constructed of them. Such buildings could be read as metaphors for society, signs of a social order.

Such a reading seems to have dawned on Richard Reddaway.4 Drawing on the architectural sculpture of those times, Reddaway has produced a series of sculptures and photomontages in which identically posed figures are stacked or otherwise conformed in regular arrangements. The architectural derivation of the works is spelt out in titles like Rib, Hammer Beam, Capital, Ogee, Lintel, and Jamb.5 Reddaway sees his works as utopian. He speaks of society like a body, as being healthy or unhealthy: ‘I am interested in what is social. I am seeking to portray the mutual relationships between individuals, the working system that makes up our society. The individual does not live alone, but in relation to others … Just as a healthy society, in order to be healthy, needs to recognise the potential of its every member, the individual needs to recognise their part in society.’6

Reddaway says he is ’seeking to portray the mutual relationships between individuals, the working system that makes up our society’, but obviously he is not portraying social relations in all their complexity, individuality, and actuality. All the relationships are portrayed as equal and identical—certainly not the case in our society. Rather his works offer exercises in a metaphorical social engineering. They are symbols, projected societies, model communities.

Reddaway has been concerned to find his métier, his social role as an artist. He found it by looking back to the more traditional, anti-individualistic, holistic societies of Romanesque and Gothic times. In those days, the church provided the focus for society, and artists made signs and symbols for people to live by, not just things to hang on the walls in exhibitions. There is a nostalgia for such times in Reddaway’s work, a wish for a society in which ‘the individual does not live alone, but in relation to others’. A wish to have it all back.

In the photomontages, it is the artist’s own body that features—his photographically cloned body arranged and regimented according to geometric principle. This is not narcissism in the sense of a portrait of the artist as a young delectable body, although it may be politically narcissistic as far as presenting the ideal society as a constant affirmation and duplication of oneself. Reddaway envisions himself as a nobody, as everybody.

Today, such aspirations are easily read as dubious politics. Fascism in Germany and Italy, Stalinism in Russia, and the Cultural Revolution in China, all sought to submerge individual identities and wills into a single mass identity, a general will. This was either premised on a utopian desire for the general good, or with a more insidious need on the part of the state to mobilise the population for its own ends, rendering it obedient, mobile, efficient. Against this backdrop, Reddaway’s mummified acrobats—bound, blind, identical, intertwined—are more likely to be taken as alienated, depersonalised and oppressed than as happy, liberated, cooperative workers; more likely to be seen as dystopian than utopian. A chain-gang of figures, they know their place, play their part and put their best face forward—no face at all. Certainly Reddaway’s statement—that ‘just as a healthy society, in order to be healthy, needs to recognise the potential of its every member, (so) the individual needs to recognise their part in society’—seems a little sinister. A possible implication is that it is positively unhealthy, a crime, to be an individual, to deny one’s role as a mere ‘part’ of society. Nevertheless, there is perhaps an acknowledgement in Reddaway’s work that the dreamed of integration of art and life, of social bodies into social body, cannot happen. His sculptures are not whole buildings but fragments, isolated supports that no longer support anything. The body-building has fallen or been torn apart. It is a ruin, useless. We have only tattered relics to hang on walls.

In Derrick Cherrie’s work also, the body is related to architecture. Cherrie continually references the notion of the body-as-institution to the building-as-institution. He collages generic figurative and generic architectural elements to construct hybrid body-buildings.

In the installation Untitled (Blue) (1986), a blue figure is laid out on a single bed. The figure is not round and fleshy like the human animal, but rectilinear and blocky like a building. A door opens between its legs onto a room containing a double bed. By a certain logic, the figure is thus female—this is her womb. Two seated (presumably male) figures contemplate her from raised platforms. They are smaller than her, but, notably, not small enough to get into the bed.

Behind these sculptural elements are four huge drawings. One of them shows a figure, sitting, like the blokes on the platforms, on a double bed, like the one in the giant woman. The room the figure occupies is like a cell. One tiny window on high lets in a little light. This man may have penetrated the sanctum, but he sits on the bed alone, in pretty much the same position as the others. An adjacent drawing shows the exterior of a building. By a cinematic logic, this building would be the building containing the cell. Certainly, it looks like a very nasty institutional building; a prison, an asylum, or school. This giant woman therefore can be read not only as a kind of institution, but as incarceration.

The bodies in Cherrie’s works are architecturalised, generalised into blocks. The figure takes on the severe lines of its institutional environment. Ironically, the figure, in having been stripped of particularity in order to signify simply ‘the human’, loses those qualities we value as human. The generic figure is inhuman. Such inhumanity is further evoked through the style, material, and finish of Cherrie’s work. There’s an impersonal feel to the impeccable plywood objects; their flat, matt, unmodulated surfaces deprived of gesture, spontaneity and traces of making. And there’s the de-personalised nature of the huge drawings. Having been reproduced by hand from tiny sketches, they retain the ‘brooding chiaroscuro’ of the originals. But, they look like what they are, small drawings that have been enlarged. The effect is one of dislocation. The autographic authentic mark here appears mediated and inauthentic.

.

Stumped

Gavin Chilcott’s paintings and drawings are often populated by wooden block figures, faceless stumps, sometimes with little arms and legs, sometimes without. These lumbering figures are inexpressive—literally and metaphorically wooden. They’re like prematurely-born sculptures, awaiting further chiselling, a bit of character development. The figures are brought out in a variety of situations. Sometimes fictional, at other times they stand in for people Chilcott knows, as he illustrates true stories from personal experience.

The Bee Sting + Dr Batt (1985), for instance, tells the true story of how Stephanie Chilcott was ‘saved’ when Dr Batt gave her an injection following a potentially fatal bee sting. (The work now hangs in the Batt surgery). In this drawing, both figures are wooden. They are virtually the same figure, differentiated by role. Throughout Chilcott’s work all manner of friends, relations, chums, famous people, and the man himself, have been decked out as chips off the old block. By depicting this range of persons as identical and equivalent, Chilcott casts them as nobodies, thus rendering his/their personal history as part of some kind of archetypal history.

Francis Pound suggests that these stump-people could be read in relation to the work of New Zealand’s Dead Tree School.7 In such works as Christopher Perkins’s Frozen Flame (1931) and Eric Lee-Johnson’s Slain Tree (1945), the dead, chopped-up, or burnt-off tree or tree-stump is anthropomorphised. The sorry state of the tree becomes an ideogram for the alienation and spiritual poverty of the human who would burn it or cut it. That alienation is clearly charged with meaning.8 In the face of this local art history, Chilcott’s stumpy figures could be read as parody, making fun of such earnestness, making fun of the thought of recognising our essential selves in dead trees.

Chilcott’s works are generally read as lightweight, flippant, even trite. Pound has noted: ‘If some of his titles might suggest some painful performance … all anguish is deflected by irony.’ And yet the effect of Chilcott’s presentation is more morbid. Irony creates a distance, certainly. But the very need to create distance suggests something is too close at hand, too close for comfort. Flippancy and earnestness are alternative strategies for dealing with anxiety.

Posing as a stylish tubercular, Chilcott describes his artistic occupation as one of ‘coughing blood’.

.

The Body in Bits

Our sense of personal identity is confirmed by our perception of our bodies as discrete and unified entities. Before attaining a unified body image, the child has no independent identity. And, as adults we employ various functions, especially the ego function, to conceal the unconscious knowledge that we are not unified; our body is not whole, but in fact bits and pieces.

Significantly perhaps, teach-yourself-how-to-draw-the-body books usually advise the student to start by conceiving his subject broadly, as a set of basic, discrete geometric forms. One must sketch these in first, checking the basic proportions, then refine the figure with increasing detail. Slowly the basic geometry is humanised, transformed into an individual; a body with a distinct identity. This conception of the body is parodied, reversed, in Derrick Cherrie’s Standard Figure (1988).

Cherrie’s figure is composed of a number of blocks and cylinders of various dimensions, arranged to form a schematic figure. Over these forms the artist has papered pages from medical textbooks illustrating the inner workings of the body. Cherrie corrupts the hierarchy of surface and depth.

The arrangement of basic forms looks precarious, unstable, about to come unstuck. In fact they appear to have been arrested in the very process of toppling. (The diagrams too show the body fragmented.) The possibility of the collapse of the body, and the death of the self, is foreshadowed by the incorporation of a skull into the uppermost head section, turning Standard Figure into an allegorical figure of Death.

Fragmentation of the body is also evident in Denys Watkins’s Partially Dislocated (1985). In this work, we discover bits of body flying about, accompanied by some furniture and a generic Mexican. Seeing the dismembered limbs, our initial response is to imagine that some body has been blown apart; thus we assume that we can find all its bits and piece it back together again mentally. Looking closer we discover that there are not two but three arms, and no body to speak of. We realise we don’t know which if any of the parts should be attributed to the head, which similarly floats dismembered. Our assumption, and our desire, that the figure be a whole is thus foregrounded. Again, we have been caught attempting to project an identity onto a bunch of bits.

.

Social Body

Generic figures emerge in John Hurrell’s black map paintings, but largely by accident.

Hurrell made these works by taking images by other artists and transferring their outlines onto arrays of New Zealand city street-maps. Where the lines crossed roads, those roads were retained in full; the rest of the area being obliterated in black. These works were first intended as critiques of nationalism in New Zealand art discourse and practice.10 But when read with no knowledge of the source, or no inside information as to how that source was processed, they are open to quite different interpretations.

Many of these works, including 43° 32’ 7’ S. ‘Schwebender Rot’ 172° 38’ 15’ E. and 43° 31’ 40’ S. ‘Sotto Vento’ 172° 38’ 13’ E. (both 1986), feature single figures. Simplified to outlines, these figures take on a generic, thus allegorical, appearance. City and body are superimposed, so the city can read as a body, and the body as a city, with streets and roads as arteries or nerves. The city being a home for many smaller figures, this body-polis could be read as a social body, the smaller figures in their daily travels obliviously, or deliberately, tracing the form of a (cultural) body. One could compare these works of Hurrell’s to those ancient earthworks where human figures are traced on such a scale that only God (or today’s aeroplane passenger) could read them.

.

Proper and Grotesque Bodies

The body is regularly employed as a metaphor for society, ‘the state’. The sovereign power is ‘the head’, directing its ‘organs’ and ‘limbs’, with the populace as its ‘body’. Society then, like the body, can be healthy or unhealthy, efficient or inefficient, proper or grotesque. The generic body as one form of the proper body, perhaps the extreme example of bodily propriety, again appears politically conservative.

Incomplete, unlimited; protruding, bulging, sprouting; cancerous, mutant; the grotesque body is absolutely at odds with the generic figure. While the latter is marked by an absence of peculiarity, the former is distinguished by an excess of it. In contrast with the proper body, the grotesque body resonates as an image of unreason. Such unreason can similarly be read in social terms, the grotesque body offending not just the logic of bodily function, but also, by extension, the logic of social function. The grotesque body suggests a perverse kind of social body, simultaneously refuting the inevitability of the existing social order.

In Derek Cowie’s The Right Arm’s Pouring (For Children) (1989), a generic figure appears alongside a grotesque body.’11 The latter is both a singular creature and a population in its own right. It is a body, but one whose parts have been replaced with a profusion of heads. It has many wills but no limbs for them to drive. This revolting body appears to be expanding, exploding—a state of anarchy, nonetheless ecstatic. Meanwhile, a generic figure, oblivious, walks a tightrope. While the grotesque body expands, the generic figure is discrete. While the grotesque body is informed by a bunch of heads, venturing in different directions, the generic figure concentrates on maintaining balance. These two bodies represent different strategies for living, different value systems.

But, while the generic figure can be a conservative, he can also be a perverse and wilful little man. In Little Purple Girl (1988), a generic figure and a grotesque body are again juxtaposed. The little purple girl has two faces. One, where a face should be, on the front of her head; the other, in her chest, its blind eyes filling in for her nipples. The generic figure leans forward, ministering to one of those eyes with an eyebath—a gesture that might be caring or corrupt, paedophillic, perverse. Is this little guy getting his thrills, feeling up the girl? Perhaps his act references a proprietorial obsession with impropriety—propriety’s need for the very margins which define it. Rather than appearing mutually exclusive, proper and improper are shown as implicated in some kind of relationship.12

.

Little Rascals

In Riduan Tomkins’s paintings, diminutive, faceless, schematic figures are placed in abstract colour fields. Without the figures the paintings would be read as reductive modernist abstractions. The figures however cue us to read these ‘abstract’ fields as spaces literally occupied. For instance, a figure surrounded by blue can be read as falling through the sky, like a skydiver, or floating in water, a swimmer. Figures partially painted out, or in, can be read as sub-merged in or emerging from the field. Tomkins’s figures strike a strictly limited number of poses. Several bodies in the same pose often appear in the one painting. Again, there is a sense of the figures having been stamped out. The males usually appear side on, active, arms outstretched. Perhaps pointing. Perhaps reaching out to touch, to grab hold of something, some chunk of the pictorial architecture, or someone. Perhaps offering a handshake, hoping to close a deal. By comparison, the females are generally more sedate, ’passive’, almost always frontally posed, almost always with hands behind backs. Tomkins’s figures can be naked or clothed. They can be involved with one another, but, more typically, float independently, apparently oblivious of one another. Tomkins’s works, with their figures lost in space, seem to reference Romanticism. In romantic works, such as Caspar David Friedrich’s Monk by the Sea (1809), human figures are often rendered anonymous—nobodies—in the face of the sublime enormity of nature. Yet, Tomkins’s figures don’t seem too perturbed. On the contrary, they are irreverent, cheekily disrupting and disordering the abstract turf on which they trespass. Further, impersonal in their application of paint and often brightly coloured, Tomkins’s fields are not ‘deep’ in either sense of the word. Tomkins cheerfully compromises sublimity with banality and cheek.

.

Ecce Homo

We see generic figures every day of the week, in different situations, making a variety of points. These Jacks of all Trades are assigned many tasks.

The generic figure has no particular identity. He can be a conformist, or a little rascal; obedient or perverse; can signify the whole population or its most pathetic example. What nobody means depends on context. In Cowie’s Day Care, he is a snappily dressed bourgeois, operating at a comfortable distance from his collegues. All is decorum. In Vivian Lynn’s Playground, however, nobody is naked, emaciated, painfully twisted, a cog in the system. Like the workers in Metropolis, nobody here represents the horrors of an exploitative system. We are normally concerned with the generic figure’s particular meaning in particular situations. Consequently, we seldom consider what the generic figure means as a generic figure. Doing so, forces us to reflect on that cliche of clichés, the human condition. Being simply human, definitively human, the generic figure’s condition is ‘The Human Condition’, even though perhaps not the condition of humans.

.

- The skirt is not part of the female body, but an attribute, a role, a uniform. Freud argues that men read women’s difference as their lacking the phallus. But Mr Toilet Door also goes without. If he had a penis, it would make him explicitly a man, and then he couldn’t stand in for the species. So, oddly, it may be that the women’s lack is actually signified by an addition, and man’s addition by a lack.

- (Melbourne: Echo Publishing Company, 1902).

- This paragraph was written by Stuart McKenzie.

- Certainly, he interprets the order of such sculpture as implying egalitarian content, whereas, in fact, the reverse is true.

- Sometimes Reddaway’s works are based not on architectural supports but on architectural decorations such as friezes or entablatures.

- Artist’s statement, 1987.

- Francis Pound, ‘The Stumps of Beauty and the Shriek of Progress’, Art New Zealand, no. 44, Spring 1987: 52–5, 145.

- See Michael Dunn, ‘Frozen Flame and Slain Tree: The Dead Tree Theme in New Zealand Art of the Thirties and Forties’, Art New Zealand, no. 13, Spring 1979: 41–5.

- New Image: Aspects of Recent New Zealand Art (Auckland: Auckland City Art Gallery, 1983): 20.

- See John Hurrell’s statement in Louise Beale Gallery Newsletter, no. 81, March–April 1986, np.

- This work is not in the Nobodies exhibition, but it will be on display in the National Art Gallery as part of the touring exhibition Constructed Intimacies. It is also reproduced in the catalogue for that show.

- Stuart McKenzie first voiced this interpretation. He writes: ‘Perhaps … the threat posed to the constrained or social imagination by the grotesque body is not unserviceable. In other words, the perverted order might be seen as an expedient effect, a demand even, of the privileged order; the authority of which is endorsed by having its interdictions clarified, its margins made explicit …’. ‘Disgust Discussed’, Disgust + Neglect: Introducing Derek Cowie (Auckland: Artspace, 1989), np. McKenzie’s interpretations of Cowie’s use of grotesque bodies are the basis of my discussion here. See also Stuart McKenzie and Robert Leonard, ‘The Systematic Derangement of the Body: An Iconographic Study of the Work of Derek Cowie’, Art New Zealand, no. 51, Autumn 1989: 58–61, 104.