HOTA Collects (Gold Coast: HOTA, 2021).

Photorealist painter Michael Zavros celebrates the good life, picturing it in his art and embodying it in his glossy-magazine lifestyle. His children are part of the equation. Since 2010, he’s been painting daughter Phoebe. In 2017, shifting to a younger model, he began painting son Leo too. Chips off the old block, they love to pose, and Zavros revels in their beauty as a reflection of himself; he describes his Phoebe paintings as ‘self portraits’. But it isn’t all fun. Zavros represents his offspring in a time of anxiety over the sexualised depiction of children. Perhaps this anxiety is his true subject.

Consider two entangled works.

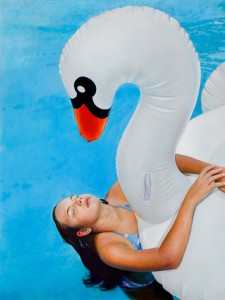

The small painting Phoebe Is 11/Swan (2017) finds Phoebe in the family pool, eyes closed, head back, arms clasped around the neck of an inflatable swan, its red phallic beak looming over her. Those grounded in art history will recall the Greek myth, where Zeus becomes a swan to ‘seduce’ Leda. There are racy depictions of this by Michelangelo, Correggio, Rubens, Boucher, and others. Zavros’s painting could be viewed as part of this pervy tradition, or not. As there’s no clear reference to the myth in the work, we can’t definitively pin such associations on the artist.

But a larger painting Zavros produced the following year complicated this. It looks like a production still for the earlier one (although Phoebe’s swimsuit is different). Downplaying the intensity of the Phoebe/swan connection, it introduces a third party, a putto, Leo, bare bottom up, riding the swan, now obviously a harmless pool toy without monstrous romantic agency. By contrast, this wider view shows how the sexual suggestiveness of the earlier picture emerged from Zavros’s choice of viewpoint and cropping (from artistic decisions, not intrinsic to his subject). And yet, while the later image downplays the sexual dimension, its title—Zeus/Zavros—emphasises it. And the meaning of the earlier work is transformed by the title given to the later one.

Is Zavros messing with us? At face value, both images ostensibly document what his innocent children innocently do in private. But, translated into art, the images become suggestive. Instinctively, we sense a problem. ‘But where is the problem?’, Zavros seems to be saying. How does the snake find its way into this garden: through what the children do, what the artist brings, what we as viewers bring, or in some interplay of these? To what extent does it intrude via the framing force of titles?

Zavros plays a shell game. He’s so meta.

.

[IMAGE ABOVE: Michael Zavros Zeus/Zavros 2018

BELOW: Michael Zavros Phoebe Is 11/Swan 2017]