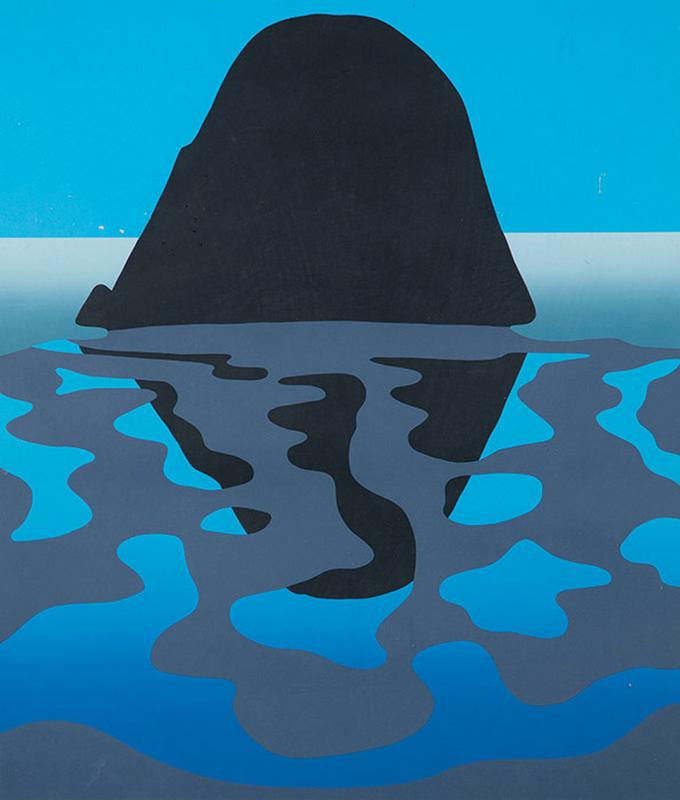

Midwest, no. 2, 1993.

Michael Smither is famous for his images of the Taranaki landscape. Indeed, it is a landscape he helped invent. For many, it is hard to pass through the region without seeing Smithers everywhere. One is left wondering if this is because of the artist’s faithful aesthetic or because his work now directs our seeing. Smither’s images have become second nature. Smither’s colonisation of the region is due less to the prominence of his paintings in museum collections than to his tireless dissemination of inexpensive screenprints. Not only has screenprinting permitted him great visibility and accessibility, the process is also ideally suited to his aesthetic and philosophy. Unfortunately, the ubiquity and popularity of these works has also made them strangely invisible. Although they are central to Smither’s project as an artist, little has been written on them and they are seldom seen in museum shows. They are an important but neglected part of his oeuvre. Late last year, I put together a small retrospective of Smither’s screenprinted landscapes. The exhibition featured works from the 1960s through to the 1990s. Smither dedicated the show to his father, the late R.E. Smither, a commercial screenprinter who collaborated with the artist on his prints for many years. A week before the show opened, I talked to Michael Smither.

.

Robert Leonard: How did you come to start screenprinting?

.

Michael Smither: My father was a screenprinter, from when I can first remember. I grew up with the process, crawling around on the floor, watching out the corner of my eye, fascinated by what my father did. I didn’t do screenprints myself until 1963. I don’t know what made me want to do them. The desire to produce images that were available to people at a reasonable cost came into it somewhere, but it wasn’t the initial reason. I loved the clarity you could get with some of the screenprinting techniques my father used; just cut stencils, very simple. There was something about using the knife. I can remember being interested in the knives my father used to cut his stencils long before being interested in the printing itself. They were scalpels like they used in the hospital. I was fascinated by the process of cutting. I still get a thrill out of seeing a sharp edge in an image, and you can’t get a sharper edge than with silkscreen printing.

.

What kind of screenprinting did your father do?

.

My father was very clever. He screenprinted posters and hoardings and signs. He was doing lots of shop displays, Easter decorations, Christmas decorations, sale decorations, that sort of thing. He would put samples in his car and drive off around the country and sell them to shops and people. He made paper sculptures too. I remember gigantic fans that opened up three or four foot high, as decorations for drapers’ shops. He made Easter bunnies and birds that balanced on the tops of bottles. He had machines that die-cut paper. He made cardboard boxes.

.

Did you see him as an artist?

.

Above all, my father was a technician, rather than a creative person. So, later, when I produced a painting he liked, he would want to make a print of it, to reproduce its look through screenprinting technique. In his mind, the triumph of the printer was taking what the artist had put down and making a faithful reproduction of it. My print St Kilda Beach, South Island (1976) is taken from one of my paintings. It’s complicated, containing twenty-one separate views of a beach. My father did it completely on his own. It needed about thirty-seven different screens. I just came in at the final stages and said that needs heightening, that needs pushing back, and let’s do something with that. But it was just tidying up details, really.

.

So, you weren’t involved much in that particular print.

.

I was always against the idea of reproductions of paintings. So a lot of tension developed between my father and I, because I loved screenprinting for its simplicity, but he loved it for all it could be made to do, for instance reproducing the look of painting or lithography or photography. He would want to do it one way and I would say, ‘No, I don’t want to do that. I want this to be a print.’ At times, I had to go along with him because I had to satisfy his needs as well. And so, as we worked, I relaxed into the process and often invented techniques myself, such as working directly onto the screen with crayon and wax. So I was able to go along with him to some point but I always wanted to get back to the simple flat shapes and cut edges. It was funny, because I was trying to honour his craft, and yet he was trying to honour mine, so we were at cross purposes at times, but out of that tension arrived some amazing prints.

.

Your landscape prints seem secular. There’s nothing specifically religious about them. But knowing you, I would assume them to be very religious in intention.

.

The first images I saw were religious. I went to church every Sunday, from when I can first remember. I sat in the church and looked at the altar with the crucifix behind it, and, all around, images of this person being slaughtered in the Stations of the Cross. Powerful images to a child. As a child in a Catholic school, I saw lots of images of three crosses on a hill. The hill became a central image. And it wasn’t just that one hill. Every hill you looked at had the possibility of having three crosses on the top of it, and everything that goes along with that.

.

Pretty scary when you live in a hilly country.

.

Right. Just look what it did to McCahon. It drove McCahon bananas. He went around seeing doom and gloom in every bloody hill there was. And I tried to react against that by painting the hills in a sensuous way, but now I see they came out much the same because I was driven by that agenda underneath.

.

You say sensuous. Are there sexual undercurrents in your hills?

.

Yes. Very, very definitely, but not deliberately. I didn’t set out to say here is a tit and here is a bum. It just turned out that way because that’s what was on my mind.

.

I suppose it’s a drag, whenever you see a breast or a buttock, thinking of the crucifixion.

.

It does have that overtone. Sensuality and sexuality were something that men of my generation, and especially Catholic men, paid for dearly. We had to confess our sins every Saturday, and our sins were mostly sexual sins, I’m afraid. Our attitude to sex had to go underground and mine went underground and came up underneath the hills of Taranaki and the hills of Central Otago. Whatever hills were around turned into sexual experiences. And then finally I crucified those sexual experiences in the Rita Angus crosses.

.

Many of your prints of the landscape feature very centralised iconic compositions.

.

Yes, like Untitled (1977)—with the seagulls flying in and the shadow of the wave breaking—where there’s the desire to draw people’s attention to the fact that such perfect moments exist. That sort of central image is clearly related to the crucifix, having your cross sights on a thing.

.

Strange to compare such a peaceful image with the horror of the crucifixion.

.

But the crucifixion works in the same way. I was born at the beginning of World War II. When you see the whole world thrown into that sort of confusion, when you’ve got bodies putrefying on the bone, Matthias Grunewald looks kind of tame and the crucifixion becomes almost comforting. The crucifixion seems to make some sense while the carnage of the war made no sense at all. Christianity attempts to give sense to the whole business of suffering. Now, I think that’s a way of looking at the world that we have to break with. Now, I’m more into the taoist approach: shit happens, just let it go, get on with your life.

.

Some of the landscapes are iconic, singular, but others are just the reverse. They’re serial, like the stations of the cross. The iconic thing is fragmented in a sequence of views.

.

It’s seeing things change. So, you walk along the beach, and there are four islands, and, say, a promontory, like Paritutu, as the central axis to those islands. As you walk, your relationship to the islands and the promontory, and their visual relation to one another, becomes really interesting. You realise you are walking along a sort of harmonic. So, you walk for a hundred yards and then suddenly something goes bing, and it’s the right moment. Then you walk for another fifty yards and bing. It does it again. And then you walk for twenty-five yards, and so on. They are points of arrival like notes spread out in a chord of music. Some of those works also relate to my time as fisherman, where I’d use the position, the alignment, of rocks to find my way back to the perfect place to fish. So when this rock was here and that one was there, you knew you were on top of the reef, and you put your line down and you caught a fish.

.

Much of your work seems to be about purity. You present images of a clean and unpolluted landscape and you present them in a clean and unpolluted style. Is there some ethic behind this?

.

The other day, I was talking to someone about some glasses I had just painted. He said, ‘There’s no distortion. If you have glasses on a table like that, when you look through them, what’s on the other side would be distorted.’ And one of things I have done in my art is to eliminate distortion. So, when you look into one of my rock pools, you see the rocks as they ought to be seen, not as the way they really are seen, and a lot of these prints are about that. The images are simplified down to the way it ought to be, not the way it is. Making an icon is actually saying, this is the way it should be. That’s my Catholic upbringing: the idea of purity, the idea of cleanness.

.

I suppose the screenprinting process encourages that kind of thinking.

.

I’ve never done etching and that’s why. Screenprinting really suited me for getting that clean look.

.

The colour in the prints seems really unnatural. To what extent is it derived from observation?

.

Sometimes it looks very abstract, but it is based on reality. I’d go for a walk along the beach and think, oh yes, powderpuff pink sky, black rocks, grey sand. Then I’d go to the studio, and look at what inks were available. Screenprinting inks come in tremendous colours, with beautiful colour-sample swatches. I’d flick through them and think, yes, I want that colour. I also experimented. In screenprinting, you end up with a certain amount of colour left over, because you always mix more than you need, so you don’t run out in the middle of a printing. I used to randomly combine the leftovers to make new colours. So, in the prints, there are a lot of these experimental colours. The pure colours stayed pure, but the intermediate colours and greys I got almost by accident. Wonderful strange colours.

.

When did your approach to colour become theoretical?

.

When I first started, I loved bright colours, but I had no idea how to bring them together. So, I took the approach of the early renaissance painters, that you could put any colour alongside any other colour as long as the form held the colour. That was the technique I used until I was thirty-five or forty. Then, I started thinking, hey, there’s a whole lot of theory about colour. At that point, I started adopting a more academic approach to colour. I started relating colour to sound, relating the spectrum to the octave and playing with the ‘harmonics’ of colour. I would have air, sea, and earth in an image. That would offer a range of harmonic possibilities relating to one hue, say red. So, the red could be the sky. That’s fine for the sky. So, blue green, which is the harmonic that goes with red, would be the sea. And then I would have to find a colour that went with the land, and that could be orange in the harmonic scale. But, you can’t have an orange piece of land. That doesn’t make sense. It’s the wrong colour. Unless you make it an island out at sea with the light on it. So, that’s the way the colours were decided. I always tried to relate my colour to the element’s true colour.

.

So, how did you arrive at your harmonic theory?

.

During the Polyphonic Chords exhibition (1980–1), I did an experiment. I had twelve bits of card painted in the twelve colours of the spectrum. I asked people to shut their eyes. Then, I played the same note over and over, asked them to feel the pieces of card, and tell me when they got a reaction through their fingers. And I kept notes of what happened. People got reactions, like a little electric tingling, but these responses did not fit with my expectations. I thought if I played A, red would be the colour people would feel. But they felt blue-green, they felt orange, and they felt violet, and that really confused me. What happened was that different people were reacting on different harmonic levels. They weren’t picking up on the note, but on its harmonics. That’s what lead me to produce the harmonic chart. When I brought the results of the experiment together with what I already had, I found it all added up. Colours are vibration of light. And, it affects people in different ways, simple as that. You may not be responsive to a particular colour, but the harmonic intervals will still work.

.

You say your last print Rocks in Sand Pools (1991) is the last you’ll ever do. It had no color in it at all. It’s just black rocks on a white ground.

.

All colours actually exist within black and white. McCahon did his experiments with colour too, but he came to the conclusion that compositional structure was more important. That’s why his later works are all black and white. That’s the conclusion I’ve come to too. I still use colour though, but I relate it much more strongly to structure. I’ve now come full circle. I started off with strong ideas about structure, then colour became dominant, now I’m back to structure again. The imagery of that print has me going full circle too. Some of my early prints were of the Holy Family. They were images of people. That lead me into my adventure in printmaking, where I would deal mainly with iconic landscape. This last print is again based on the Holy Family idea, but instead of using figures I use three rocks to represent Mary, Joseph, and Jesus.