Pleasures and Dangers: Artists of the 90s (Auckland: Longman Paul, with Moet et Chandon (NZ) Art Foundation, 1991).

These works should be in an institution!

Why, what’s wrong with them?

.

In the early days, the father of American conceptual art, Joseph Kosuth, demanded an art practice aligned with analytic philosophy. In the essay ‘Art After Philosophy’, he distinguished the new ’conceptual’ approach to art from the traditional one. In short, the old approach admits things as art because they resemble and reiterate previous works of art. It’s a deeply conservative attitude, affirming an academic, static notion of art’s nature. By contrast, the conceptual approach is dynamic, recognising artworks by how they function. And what the conceptual artist values in artworks is how they function to question, analyse, and enlarge the concept ‘art’. The conceptual artist questions received wisdom and makes new propositions as to art’s nature.

Writing in 1969, Kosuth was concerned by how conceptual art was being written up. Instead of being defined by its desire to question existing categories, conceptual art was identified with particular ideas, media, and stylistic persuasions, making it simply another category. Confined and confirmed as just another ‘ism’, conceptual art could be recuperated by the attitude it had tried to displace.

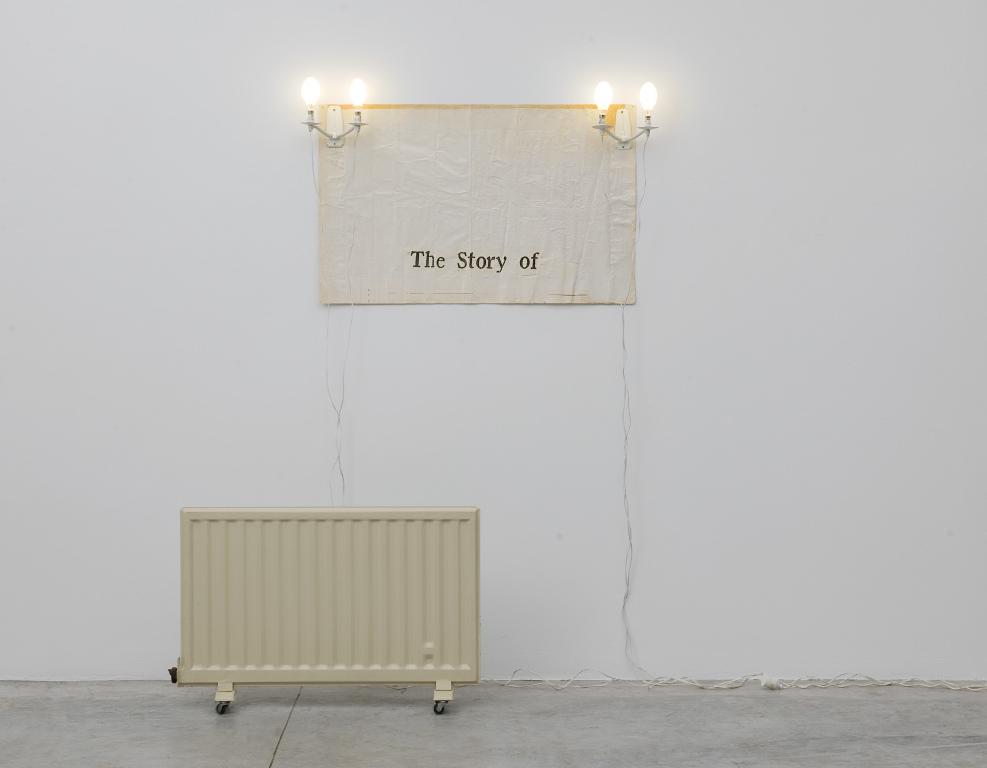

In her recent installations, Merylyn Tweedie satirises the seriousness and radical pretensions of conceptual art (as outlined by Kosuth). In these works, objects and texts are placed in precise arrangements which fetishise ‘the conceptual-art aesthetic’. Her works cue us to read them as conceptual art; cryptic and cool, demanding ponderous consideration. But, on closer inspection, the rigorous intelligence we expect of conceptual works is lacking. The arrangements are gratuitous, arbitrary, senseless: the various contents do not converge to make a philosophical point, but resist reduction (or enlargement) to any such explanation. Tweedie has staged the appearance of meaning, not its substance. In the face of the prevalent concern that there’s nothing to avant-garde art, that it’s all an elaborate fraud, Tweedie presents her own art as something of a con.

Tweedie’s use of found objects is not a radical move, but follows in the footsteps of the original charlatan Marcel Duchamp; the originator of the ready-made, the grand-daddy of conceptual art, Duchamp, you will remember, was a procrastinator, taking an unreasonable amount of time to finish his masterwork, The Large Glass. Soon after that he retired to take up chess as an occupation. But at least while he was busying himself with play he was still doing a bit of work, preparing himself mentally for his last great gesture, Etant Donnes, the enlarged pornographic postcard permanently installed in Philadelphia. Tweedie is lazy, but in a different way. It’s not that she doesn’t produce enough works (that criticism has never been levelled at her), it’s that she doesn’t seem to put much thought into them. Neither does she do much work in her works. Except for a bit of xeroxing and a spot of resining, her artistic role appears limited to ‘shopping’ and ‘arranging’.

Odd, Tweedie’s objects exemplify the category of jumble. Old swivel chairs, wrought iron magazine racks, dinky stackable tables, old prints, out of date hard covers, remnants of lino and wallpaper, buttons, and defunct bar heaters have all found a place in her recent work. Selected for their retro qualities, most of these objects come from around the 1950s—the time of Tweedie’s childhood. Many may once have exemplified good, functional, modern taste, but now, if they seem stylish, it is only in a bad way. Originally intended to brighten up the environment of life, to make the house a home, Tweedie found these items discarded on the roadside or in op-shops. Faded, jaded, and out of fashion, the passage of time has made them sickly. Tweedie’s installations enhance the pathos of these objects, emphasising their isolation, their loneliness. The resin coatings on the books suggest ageing and illness, giving them a golden prematurely aged look, a jaundiced pallor. Resined open or shut—either way they become impenetrable, ‘closed books’.

The fragments of text Tweedie uses are similarly obscure, not because they are from difficult sources as would once have been the case, but because they have been cut adrift from their sources—taken out of context. They suggest fragments of a biography or a narrative that might illuminate the objects. But they do not. The text in Guide to Roland Welles for instance offers a guide to nothing: ’All that night, my mind went over and over again the scene of the evening. I hardly slept. In the morning, I wrote Roland Welles the news.’

With these installations Tweedie has dropped the explicit feminist references of earlier work. (The absent Dora has been usurped by the absent Roland Welles.) And yet, Tweedie’s installations can be related to her ongoing interest in hysteria. Hysteria is classic female trouble. Psychologically traumatised, the hysteric loses control of her body in an eruption of speech from the unconscious. Recent feminist theory has validated hysteria, casting it as a protest against male structures. Similarly, feminists have cast the analytic session as an occasion to outwit the im-patient, reinforcing the male order by declaring her insane. Much of Tweedie’s work has mimicked the babble of hysterical speech, its surplus of inanity. Her boring and disordered films have been particularly successful in tormenting viewers, who could derive neither sense nor pleasure from them. In her new installations, Tweedie disrupts order by producing a dysfunctional form of conceptual art, something that at first glance looks analytic, conceptual, discursive, but proves resistant to interpretation. Tweedie’s work continues to reject analytic, philosophical values, asserting instead the resistant power of sensibility. So while Kosuth saw analytic values as radical, permitting a critique of received wisdom, for Tweedie that analytic urge is simply more of the same. Her works are deeply anti-intellectual.

But, even if all this were true, my reading presumes the rigour of an analysis. I have recuperated Tweedie’s work in analytic terms, and, what’s worse, under the alibi of advocacy. I may have appeared to have taken its resistances seriously, but I have (I hope) mastered them all the same. In fact, I have detailed its resistances only in order to master them. I have written it up and written it off. To explain these works is to take something away from them, is to put them in an institution. It’s my job.

.

Robert Leonard, Curator, Contemporary New Zealand Art, National Art Gallery, Wellington.

.

[IMAGE: Merylyn Tweedie The Story Of 1991]