15.08.22 Works of Art (Auckland: Webb’s, 2022).

–

Julian Dashper is a key figure in New Zealand art. His work frames our art history as much as it frames him. He emerged in the 1980s, at a time when our idea of the artist was changing, with the discussion turning away from tormented expressionism (Philip Clairmont) towards detached professionalism and postmodern irony (Billy Apple). More than any other New Zealand artist, Dashper exemplifies this transition. He may have been the first to get a business card.

Dashper completed his studies at Elam art school at the end of 1981. Back then, struggling creatives often sought convenient shift work while pursuing their dreams. Dashper became a taxi driver. There were two ways to do it: own your own cab and licence or work for someone who did. Owners took it easy and worked during the day, engaging others to do the less-desirable night shifts. From 1982 to 1991, Dashper drove at night, and painted by day. Taxi driving had its own lore and lexicon. In Auckland, you had to learn the local version of ‘the knowledge’ to pass the exam. In the 1980s, the titles of Dashper’s neo-expressionist paintings often referred to taxi-driver geography, particularly the locations of taxi stands and hotels.

As a nocturnal taxi driver, Dashper haunted all-night cafes and observed the city’s seedy side. The job suited him. Required to talk to randoms, he perfected his taxi-driver patter. Partly, he modelled his persona on Travis Bickle, the psychotic New York cabbie played by Robert De Niro in Martin Scorsese’s 1976 film Taxi Driver. For Dashper, the sedentary junk-food-laced lifestyle took its toll. He inevitably put on weight, as De Niro did more deliberately in order to play Jake LaMotta, the boxer who ‘could have been a contender’ in Scorsese’s 1980 film Raging Bull. And Dashper loved reciting LaMotta’s famous dressing-room speech, where De Niro was himself channelling Marlon Brando from On the Waterfront (1954).

In 1987, Dashper went to Europe and America on a four-month art odyssey that, he said, ‘forever changed my way of making and thinking about art’. He returned to Auckland svelte and jettisoned his painterly ways, in favour of the cool and conceptual. For a few more years, he continued to drive cabs and his work occasionally referred to this. For the 1989 exhibition Occupied Zone at Auckland’s Artspace, he made a wall painting of one word writ large: ‘Drive’. But was it a reference to taxi driving, to his artistic ambitions, or to McCahon’s legendary Rinso packet? (Drive was an alternative brand of washing powder.) He also created a laminated taxi-driver photo ID, identifying himself as ‘Travis 1’.

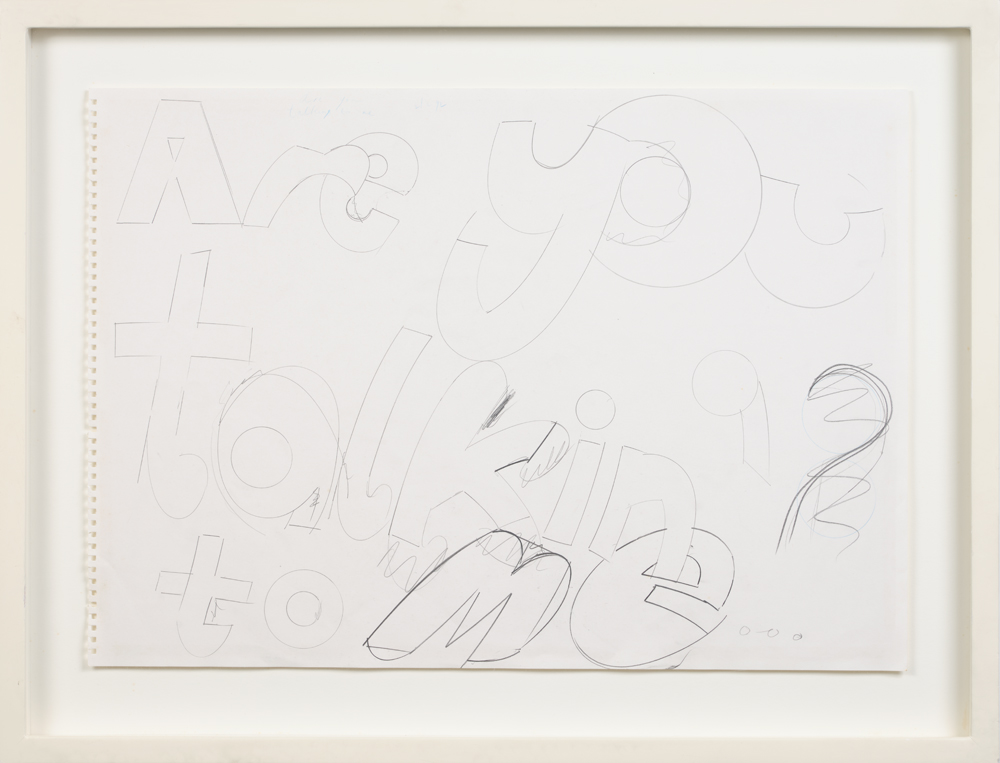

Around 1992, Dashper was commissioned to make a body of works quoting Bickle’s line, ‘You talkin’ to me?’ In Taxi Driver, Bickle is home alone, eyeing himself in the mirror, practicing menacing lines and drawing his handgun, rehearsing a confrontation with his own reflection: ‘You talkin’ to me? Then who the hell else are you talkin’ to? You talkin’ to me? Well I’m the only one here. Who the fuck do think you’re talking to?’ This monologue wasn’t in the script. De Niro came up with it on the spot in a moment of method-acting genius.

For the commission, Dashper made a series of pencil drawings and printed a typeset bumper sticker. The drawings rendered Bickle’s words in an absurd, cartoony hand-lettering style, using drafting tools, including French curves and rulers. Dashper just did the outlines, as if he might return later to colour them in. These jazzy improvised variants re-present Bickle’s words this way and that, shifting the visual emphasis, like Bickle himself repeating his line with different emphases. However, dislocated from the noir context of the film, the line is drained of menace. It’s benign. It’s Bickle as comedy, Bickle as bumper sticker.

It’s an art joke too. The line seems to refer to the drawings themselves, as if they were accusing us of talking to them, while also courting our attention. In this, they recall American painter Ad Reinhardt’s famous 1940s art cartoon, where a cubist painting talks back. ‘Ha ha, what does this represent?’, asks the viewer, pointing at the painting; only for it to come alive and reply angrily, ‘What do you represent?’, knocking the viewer for six.

Of course, Dashper was no Bickle—no toxic male. Even as a neoexpressionist, he was a campy, self-conscious one. There’s a great shot of him on the cover of Art New Zealand in 1987, taken before his transformative big trip. He’s thick set with a buzz cut, legs astride, attended by dogs. He’s standing in front of a corrugated-iron building with a gestural abstract painting beside him to match his paint-smeared slacks. The scenario is a nod to Hans Namuth’s photos of Jackson Pollock at his barn. In retrospect, the shot seems drenched in irony—a set up, a pose. But, at the time, Listener critic Lindsey Bridget Shaw took it at face value. Drawing attention to Dashper’s girth, she snipped: ‘Art New Zealand 43 showed us that Julian Dashper, not content with ripping off the ideas of Julian Schnabel … is actually beginning to look like him.’ I like to imagine Dashper turning his head to respond. ‘You talkin’ to me?’