A talk given at Sumer, Tauranga, in the exhibition Julian Dashper: Autumn 1989, 3 July 2021.

I often return to the opening lines in the essay Francis Pound wrote for Julian Dashper’s Water Color catalogue back in 1991. In ‘Deathdate’, Pound explained: ‘The museum wants the artist timeless. It is waiting for the death. Only with the closure of death does the oeuvre completely and happily begin.’ How prophetic. Of course, today, Dashper is dead (he died in 2009); so is Pound (died 2017). Both are now history, reborn as oeuvres. Rest in peace.

Born in 1960, Dashper was three years older than me. I’ve had a long relationship with him and his work. Over the years, I’ve curated and written on it repeatedly. I like to say that I ‘co-evolved’ with it, as my thinking developed alongside his. Dashper’s work was all about negotiating his relationship with art, with the art world, and with art history. It shaped the way I think about them too, the way I work.

Back in the day, Dashper could be amusing but also annoying. He was something of an enfant terrible, a prankster. He took liberties. He was a riposte to art history, while also screaming ‘let me in, let me in’. And he was. He’s been absorbed into art history. His works, which once rippled with provocation and attitude, are now pedigreed, blue chip. They are not simply art-about-art or art-about-art-history, they are art-history-art. They uphold art history. You can buy a piece of it; there are a few works left.

I like this show: Julian Dashper: Autumn 1989. It samples a key moment in Dashper’s work. Thirty-plus years ago, back in the twentieth century, he produced these charming, easy-on-the-eye, gentle-on-my-mind graphics, as he transitioned from being a Julian Schnabel neo-expressionist type to being a cooler, more geometric, and ultimately more conceptual artist.

Dashper’s work here typifies the larger postmodern turn of the 1980s, when our relation to abstraction changed fundamentally. Previously, abstraction was routinely touted as advanced, superior, the future, art’s objective and endgame. It was entangled, variously, with notions of formal and philosophical self-criticality (‘thoughts’) and notions of deep spirituality (‘feelings’). It was veiled in complex, monolithic, churchy theories—high seriousness. Abstractionists turned up their noses and kicked sand in the faces of lesser artists.

But, in the 1980s, this rhetoric wore thin. With the pendulum swing of postmodernism, abstraction was no longer understood as form, but as sign. If we no longer took modernism so seriously, it wasn’t so long ago that we had—which gave these works of Dashper’s their illicit frisson. When they came out, no-one quite knew whether they were homage or pisstake—or what was the proportion of homage to pisstake there was. Allan Smith expressed this perfectly writing: ‘Much of the work’s motive-force comes from its ability to play on the memories and expectations of high-modern abstraction while subjecting these expectations to witty deferrals and reorientations.’1

Modernist abstraction involved formal enquiry, but there’s no real formal enquiry here. Dashper wasn’t trying to forge a new language, but to mimic an existing one—something different was at stake. He wasn’t a modernist, but a mock modernist. His modernism had a dashed-off, faux, amateurish quality, like he was creating mock-ups, stand-ins, or imposters, rather than the genuine article. The work was saturated with quotation and parody. Plus bathos. If Dashper seemed to make grand claims, it was only ever to fall short. The work looked like modernism to emphasise its distance from it. It was modernism in scare quotes.

With the works massed here, one can see Dashper was knocking them out according to a formula, willy nilly, as so many arbitrary variations on a theme, foregrounding the repeated use of templates and ‘colouring in’. Perversely, as if to highlight their interchangeablity, he gave his works titles that seemed to distinguish them. I remember we included three 1988 Dashper gouaches in the 1992 Headlands exhibition: Design for a Dust Jacket on Dancing, Mural for a Disco Hall, and Logo Design. It prompted everyone to ask the obvious: ‘Why is that one about dancing? They all look the same to me.’ That said, I remember, Design for a Dentist’s Waiting Room sent one critic off on an interpretive tangent, asking if Bertie the Germ had gotten into modernism.

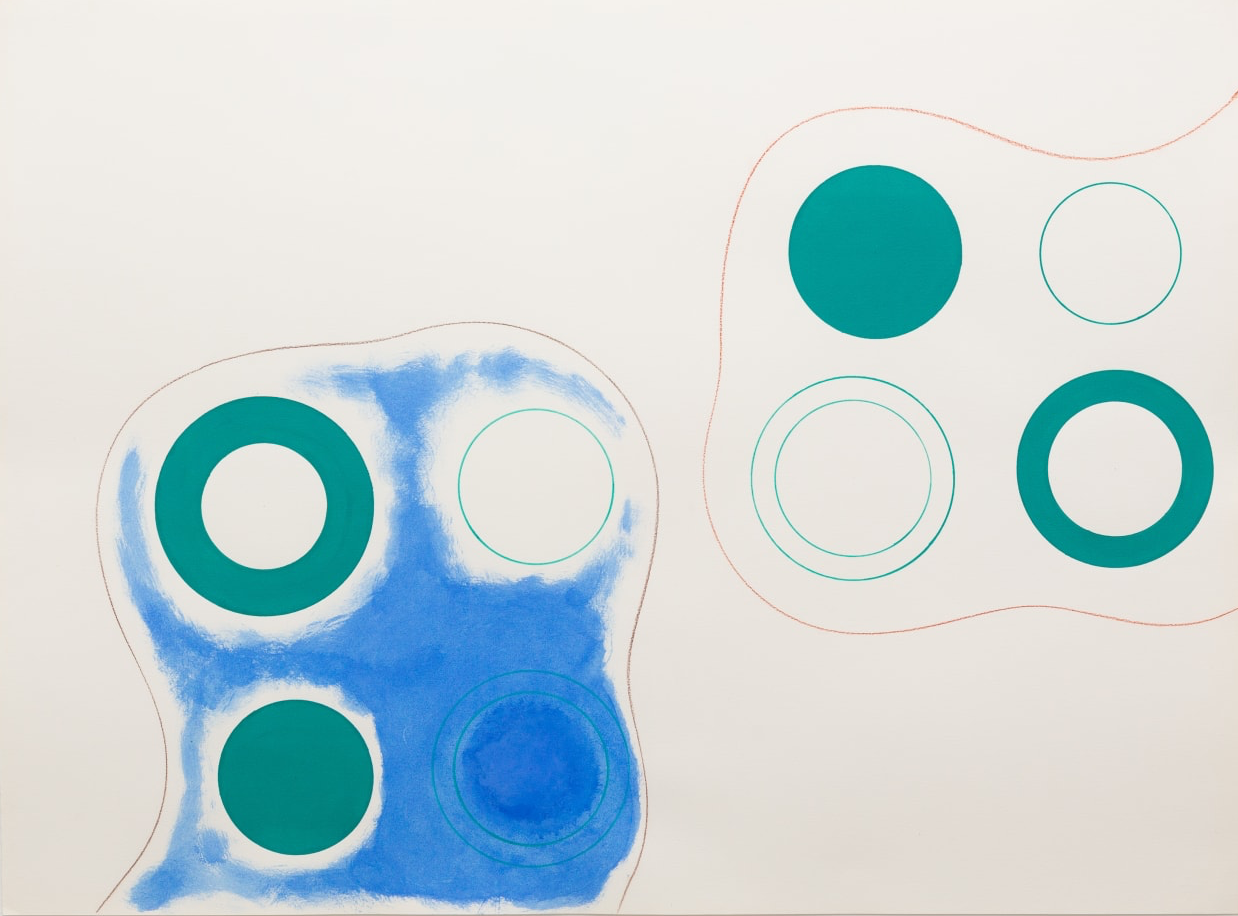

Dashper pulled the rug by linking his work to the banal specifics of everyday life. In this show, Philip Shave Green (1990) is one of a number of apparently abstract works that recall the face of the Philishave electric razor, with its three circular heads—a modern design classic. However, you wouldn’t think of that razor if it weren’t for the title, and the work really has nothing to say about the razor. The title ties this inoffensive abstract—which could be about something else or nothing—too close to a real-world referent. (Interestingly, doing my extensive Wikipedia research, I discovered that the Philisave triple-head razor was test-marketed in New Zealand and Australia in 1956, and wasn’t introduced globally for ten years. For once, New Zealand was ahead of the game. And yet, I don’t think Dashper knew that, because, if he did, he surely would have mentioned it.)

The works here play with history. The Seventies! 5 and 6 mess with dates explicitly, in a way destined to confound future cataloguers and fact checkers. They come from a series of drawings and paintings of the year ‘1960’—that of Dashper’s own birth—drawn with french curves and other drafting tools. They read ‘1960’, but they were done in 1988 in a retro 1950s-ish style, and titled The Seventies! And, of course, now, both works are in a show called Autumn 1989 staged in Winter 2021. Go figure.2

I always assumed that Dashper’s ‘1960’ works were a nod to a Rita Angus’s rebus-landscape painting, AD 1968. Angus wrote that year using images of a stick, two seahorses, and a tank. But there was no temporal confusion intended—Angus painted it in 1968. While the Angus feels like an obvious reference point for the Dashper, the upshot isn’t clear. Dashper’s ‘1960’ works aren’t in Angus’s style—although they do have something of her colouring-in quality. They don’t have much to say about her or her work. They are simply parasitic upon it.

I used to call such Dashper works ‘perverse homages’, because they made reference to canonical artists, but not necessarily to what was important about them. They prompted endless nerdy art-historical digressions by people like me. But, such references would only be ‘live’ for those local aficionados and insiders alert to them, members of the inner circle. For us, such contextual trivia override the works’ formal qualities; we are more likely to discuss the Angus connection than the way the works actually look.

With works like these, Dashper reminds us that modernism was always a multiple and messy thing. We have contrasting, contradictory ideas about it. On the one hand, it can be avantgarde, challenging, disruptive—shock the system; on the other hand, it can be domesticated and instrumentalised, making life easy and efficient, with form following function—serve the system. In the late 1980s, Dashper was playing in the space between these apparently opposing aspirations. That chasm became his sandpit.

Dashper’s works were about timing, bad timing, about belatedness, about missing the modernism bus. For him, as a New Zealander born in 1960, this belatedness was not simply temporal, it was spatio-temporal. Being behind the game—having to play catch up—was part and parcel of our provincial condition. Dashper joked that modernism had to travel a long way to get here, and got distorted and damaged on the way, dissipating as it travelled further from its source, getting lost in translation.

Dashper drew an implicit parallel between the general way edgy art gets watered down as generic corporate and domestic decor everywhere, and by the specific way it was watered down by provincial imitators here in New Zealand. Doubly diluted.

Colin McCahon is doubtless a reference point here. In a frequently cited memoir, he wrote: ‘… the Cubists’ discoveries had become a part of our environment. Lampshades, curtains, linoleums, decorations in cast plaster: both the interiors and exteriors of homes and commercial buildings were influenced inevitably by this new magic. But to see it all as it was in the beginning, that was a revelation … We were looking through copies of the Illustrated London News. The Cubists were being exhibited in London, were news, and so were illustrated. I at once became a Cubist, a staunch supporter and sympathiser, one who could read the Cubists in their own language and not only in the watered-down translations provided by architects, designers and advertising agencies … I began to investigate Cubism, too enthusiastically joining the band of translators myself.’3

Here, McCahon doesn’t seem to know if he’s part of the translation solution or part of the translation problem. Anyway, bowdlerisation and provincialism were conflated in Dashper’s mind. Wellington public artist Guy Ngan exemplified both and was the fall guy for some of Dashper’s tongue-in-cheek ‘homages’. When I look at Dashper’s Sketch for Transportation in this show, I think of Ngan’s Ministry of Works modernism.

Ultimately, with these Dashper works, what appeals is their deftness, their campiness, their knowing vacuousness, their lite touch, their preferring all this to the consequence and pomp of the modernism they recalled—their attitude. They are an antidote—a morning-after pill. They footnoted modernism, consigning it to history as a repertoire of quotable quotes. These Dashper works are utterly of their moment, as modernism became a period style, became retro. Modernism rest in peace.

.

[IMAGE: Julian Dashper Philip Shave Green 1990]

- Allan Smith, ‘Six Abstract Artists’, master’s thesis, University of Auckland, 1992: 115.

- Another painting from 1989, not in the show, of the year ‘1982’ is titled Nineteen Eighty-Four.

- ‘Beginnings’, Landfall, no. 80, 1966: 361.