John Stezaker: Lost World, ex. cat. (London: Ridinghouse, 2017).

John Stezaker is known for his distinctive, deceptively simple collages. He’s been making them for decades. His practice is based in collecting. He works with a massive personal image archive of film stills, head shots of actors and actresses, postcards, and other stuff. With the film stills, he is particularly drawn to examples from forgotten, run-of-the-mill B-films from the 1940s and 1950s. With the head shots, which are of a similar vintage, he prefers those of anonymous hopefuls who barely enjoyed fifteen minutes of fame. Meanwhile, his usually somewhat older postcards document picturesque destinations through the otherworldly haze of now-obsolete printing technologies, which sometimes seem to scramble the aesthetics of painting and photography. All these image types come in standard sizes and are formulaic. They are variations on themes.

Dated material attracts Stezaker. He likes ‘stuff that has lost its immediate relationship with the world’1—its currency. His source images advertise things no longer available: films we can’t see, thespians no longer at large, and places we can’t visit (at least, not as they were depicted). They are quaint reminders of other times, the way we were. Redundant, cast adrift from their referents and reasons for being, they are ripe for repurposing. Stezaker’s approach to collage is also time warped. He eschews the digital. He doesn’t use Photoshop to rescale and composite images, to smooth transitions between them. He uses his found images as is, actual size, enjoying and exploiting the way they line up or don’t. There’s always a degree of match and mismatch, of images accepting and rejecting one another.

Stezaker says collage ‘reflects a universal sense of loss’ and involves ‘a yearning for a lost world’.2 But that is not necessarily true; there are other approaches. Stezaker belongs to a particular school of collage, the reclusive-surrealist-nostalgic-romantic school, the Joseph Cornell school. Indeed, the American surrealist’s posthumous 1981 Whitechapel Gallery show proved to be a big influence on him. Famously, Cornell was something of a shut in, a closet fantasist. His work was a parallel world, peppered with depictions of a France he never visited and of haunting remote beauties, like Lauren Bacall. Stezaker says, ‘Cornell’s life and art … represented for me a kind of ideal, a living exile from life.’3 But what is an ‘exile from life’, if not death? Or is there somewhere else, which isn’t life or death?

.

Stezaker’s collages are about collage. Collage involves taking existing images or materials, reorienting them, cutting them, pasting them. But Stezaker often does just some of these. Sometimes he cuts and pastes, sometimes he just cuts (without pasting) or pastes (without cutting), sometimes he simply reorients. Indeed, sometimes he just selects, presenting a found image more or less as is. (He calls his uncollaged collages ‘readymades’, as a nod to Marcel Duchamp.) Through isolating different collage moves—revealing the world of difference between a horizontal crop and a circular excision—Stezaker exposes collage’s language and logic.

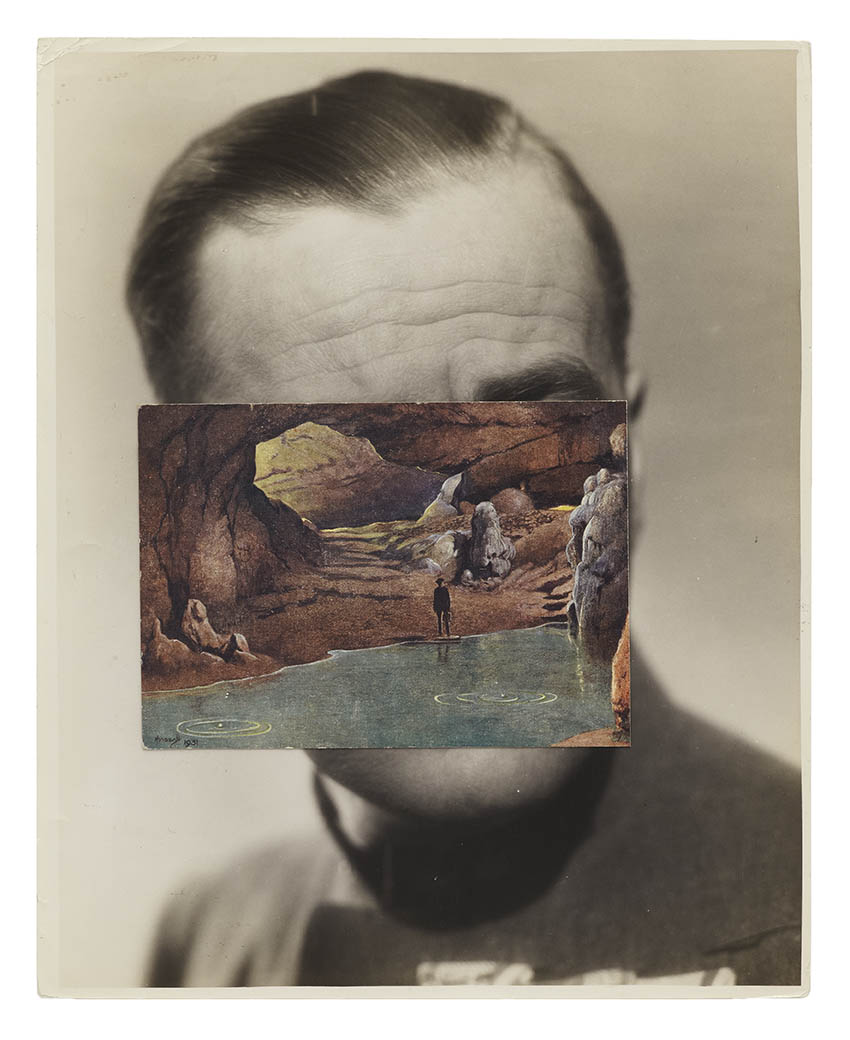

Stezaker plays out the possibilities and permutations in ongoing, open-ended series. One of the largest is his Masks. For these works, he places postcards on top of head shots, covering the sitters’ eyes. The cards add an element of disguise, intrigue, and seduction, as one might expect from guests at a masked ball. Who are these people? Forms in the scenes line up with those in the faces or coincide with where we assume facial features would be—sometimes more, sometimes less. Arched bridges, caves, and windows, for instance, suggest eye sockets; other aspects stand in for noses, mouths, hair. It’s as if the faces were caught, mid-transformation or mid-erasure. Stezaker exploits our predisposition to see faces in anything and everything (pareidolia) and to mentally intuit wholes from collections of fragments (gestaltism). However, once the initial illusion dissolves, we take stock of the contradictions: the face may be convex and shallow but the scene concave and deep; the postcard covers the face yet we register it as a window; scales and registers are wildly out; and so on.

The Masks suggest a cinematic logic, recalling the way filmmakers cut from close-ups to location shots to make a point: to show where the actor is, what they see, or what they’re thinking. On the other hand, they could suggest what we, as viewers, think, when we look into faces. Getting lost in the face of the other can be like ambling through the countryside or spelunking. Stezaker conjures a wealth of implications—expressive and metaphoric—from the simple gesture of superimposing a place on a face. Some Masks are dreamy, some grotesque, some amusing—but all are somehow deadly. Masks are inherently morbid, being dead part-faces that conceal alive ones. Stezaker’s Masks play this up, suggesting a zombie army: skull heads, rotting heads, petrified heads. It’s as if his troupe of bygone actors—now six feet under, food for worms—were still popping up for their auditions, ready for their close-ups.

Mask CCVII (2016) conflates death and the maiden. The postcard shows a rough-hewn railway tunnel opening onto a magnificent vista, combining a lake (probably) and a snow-topped mountain. It’s placed over a glamorous woman’s face; her head tilted, wistful. The railway lines push forward, into her head, as if providing an explicit track for our gaze, as if its course were inevitable. Together, the images suggest something vile (her brains blown out, Terminator 2–style) yet dreamy (landscape beauty and female pulchritude cross-referenced). Does this escapist landscape represent what’s in our thoughts in looking at her, or what’s in her pretty head? But, really, could she think anything anyway, being debrained; her now mindless head made into a picture frame? And, is that our fault? Have we drilled her brains out, effacing her with our hungry gaze—decades of looking, longing, loving? Paradoxically, all this violence is achieved by simply aligning two brands of beauty, each in itself innocent, orthodox, and reassuring. Is the artist celebrating the penetrating gaze or calling it out?

.

Actors’ and actresses’ faces are, of course, already masks—tools of their tricky trade. Stezaker often grafts their head shots, cutting one person’s in half, laying it over another’s. The first impression is of a single face; then, we see the seams. Some facial features match up almost perfectly; others don’t. Eyes and noses might align, leaving mouths and hairlines awry. Which face is real and which the mask? And, is this duplicity or duality? Stezaker’s mix-and-match identikits suggest hybrid, schizoid personalities—cracked actors. Although there’s an element of caricature at play, the effect is mostly subtle; any picturesque, cubist asymmetry being generated in an attempt to create a plausible match. For these works, Stezaker says he uses the blander, less remarkable faces from his archive, and that the combination is always an affective improvement, more engaging, more characterful. Value added.

Most of Stezaker’s composite portraits lean to the attractive, fewer to the grotesque, demented, or pathetic. While some are same-sex concoctions (the Hes and Shes), most are gender-and-genre-blending hybrids who can’t tell if they are Arthur or Martha, or what movie they should be cast in. (Are they confused or versatile?) Stezaker calls these ones Marriages and Betrayals, suggesting both how we coexist with our better halves and how male-to-female transexuals are betrayed by their big hands. Marriage and betrayal are metaphors for collage itself. Together, they suggest the temporary détente achieved between lovers, between transplanted organs and their host bodies, and between puzzle pieces that don’t quite fit.

Everything is forever coming together, falling apart. It’s the way of the world. Exploring it has long been collage’s mission. Stezaker explains: ‘Living in a culture of images is also to live in a culture that is essentially divided and fragmented. “Marriage” is a word that I use a lot because I’m trying to heal those divisions in some ways, use collage as a kind of healing process, to bring back together. Sometimes the bringing together can be preposterous and seem comic … It’s not always to do with a happy marriage. It can be a very unhappy marriage. It can be a feeling that things can never be reconciled.’4

.

We are curious. We want what we can’t have. We are fascinated by what’s hidden, what’s invisible. In his Circles, Stezaker cuts circular holes in film stills. These holes suggest where the centre of interest in the photo would have been for us, perhaps also for those depicted in the photo. Certainly, the holes now become the centre of interest for us, as image becomes frame and offscreen space moves centre stage. What remains of the image now points to the hole, offering clues to what may have disappeared behind the event horizon. We are transfixed by the nothing in the midst of the something. The hole suggests an optical blindspot, but also a psychological one, even though we can’t tear our eyes away. The hole is a question. What does it mean for the figures in the photo and what does it mean to us? The same thing or something different? Does the hole exist in the depicted world of the actors, in the real world of the viewer, or hover on the border between?

It gets more complicated. Circle VIII (2014) suggests an allegory about photography and gender. Stezaker started with a film still, a photo of someone taking a photo. Two 1940s men—generic, suited, hatted—stand on a porch. Perhaps they are gentlemen of the press. One just looks, the other aims a camera with a circular flash unit. Stezaker has removed what draws their attention, leaving a circle-hole. Poking out below it, we see a hint of a woman (a flash of dress). The blank shape of the hole rhymes with that of the camera’s flash unit, suggesting that the circle is the light of the flash, bleaching out what it was supposed to illuminate, overexposing it. But that doesn’t make sense. It’s broad daylight, so it’s unlikely the flash would be used, and, even if it was, it would not produce a hard-edged circle of light. The film’s title, printed on the still, Shadow of a Woman, prompts us to associate the camera’s flash with this ‘shadow’, even if it’s the opposite (light not shadow); or to imagine the shadow of the woman that would be cast by the flash. But where is Stezaker going with this? It’s a non sequitur.

Stezaker does something similar in his Tabula Rasas. Here, he cuts foreshortened rectangles out of film stills, suggesting blank movie screens or monochrome canvases hovering in the depicted space. It’s as though these otherworldly abstractions have invaded grey-scale world of the film stills, haunting it, like the enigmatic black monolith in 2001: A Space Odyssey (1968) or the ominous, anamorphic vanitas skull in Hans Holbein’s The Ambassadors (1533). The blanks are usually positioned to suggest the field of vision of one or more characters in the still (though our visual fields aren’t rectangular), while obscuring or excising what they would actually see. Their attitude to what was removed—be it stoic indifference, bemusement, or surprise—becomes their attitude to its removal, its absence. The Tabula Rasas cross-reference our looking at the work with people in the work looking at something, at nothing. We stare idiotically into the collage in the same way that the figures in it appear to gaze pointlessly into the void. It’s a mise en abyme.

Subtle, minimal interventions can have complex, diverse ramifications. In Tabula Rasa XLV and Tabula Rasa LII (both 2012), Stezaker makes nearly identical excisions in two film stills, to very different effect. In Tabula Rasa XLV, a generic male, in a plain black suit, seems to be looking at another man in a pin-striped one (we can see bits of him behind the screen-hole). The still is inscribed with the movie title, This Side of the Law, prompting us to think of the hovering screen as an inscrutable, accusative Kafkaesque void, with the law on one side—but which side? Is our man on the right side or the wrong? And, looking at him from outside his frame, and unseen by him, which side are we on? By contrast, in Tabula Rasa LII, a seated, suited man looks at a standing woman and man, probably (we can see her side and his trousered legs). A love triangle? Here, the movie title is So This Is Love, cuing us to see the man as a suitor blinded by affection. The blank screen hides the woman (the love interest?) but also stands in for her, suggesting she’s a screen for his projected fantasies, perhaps ours. The shape implies a puzzle for the man in the suit to solve and the work implies a puzzle for us to solve. But are they the same puzzle?

The use of the term ‘tabula rasa’—suggesting a new beginning, a clean slate—is laden with irony. As a collage artist, Stezaker never starts from scratch, but is always managing the noise of existing imagery. His tabula rasa motif is only ever visible as a rupture or rift in representation.

In the Circles and Tabula Rasas, we look through holes at nothing, but in other collages we look through a hole in one still at the contents of another beneath it, now framed by it. In his Double Shadows, Stezaker cuts the figures out of film stills, leaving human-shaped voids, silhouettes. He lays these on top of other stills, which have been inverted. The result is a confusion between figures taken out (reduced to outlines, but right-way up) and figures left in (but inverted). In a classic figure-ground switch, the absences are more legible than the presences. The Double Shadows recall those games in which a template is used to reveal a message buried in another text or image, or those head-in-hole fairground attractions that invite us to pop our real heads through holes in painted scenes. Stezaker plays out his Magritte-style displacement games—shell games of presence and absence, visibility and invisibility—endlessly.

.

The film still and the head shot are parasitic, secondary forms. They refer to another realm of representation, the fictional world of cinema. The collages Stezaker makes from them always seem to be implicated in the language and logic of movies, but at a remove or two. There’s something cinematic, but not quite cinematic, about his cuts and splices. Offering differing degrees of continuity and disjunction, they feel analogous to match cuts and jump cuts. Stezaker continually mixes his cinematic metaphors. The foreshortened rectangular apertures in his Tabula Rasas remind us of cinema screens, while circular apertures recall old-fashioned iris shots. And, when he places a postcard (of a meandering river, a torrent, a country path, a ravine, a bridge, or a big rock) over an image of a couple sharing a moment, he recalls those cinematic cutaways (fireworks and trains entering tunnels) that conflate coy euphemism and vulgar exaggeration. Masking and unmasking.

Stezaker is constantly exploring the gap between the languages of cinema and of collage. He has even made collage movies. In his flicker-video Crowd (2013), he presents hundreds of film stills of crowd scenes, each for a single frame, twenty-four per second. He runs together ‘the chorus line, the racecourse, the political rally, the bloodthirsty mob tearing after the villain, and the team of synchronised swimmers’.5 Reanimating film stills, breathing life back into them, is a perverse idea. Crowd operates at the limits of perceptibility; its images coming hard and fast, too fast to read. If occasionally we glean a fragment from the torrent—when an odd genre, gesture, or grimace lingers with us—it may feel as though it’s been wilfully implanted for subliminal effect (picking us), when, really, it is our own eye-brain that singles it out from the melange. Everyone has a different experience of the film.

.

Stezaker’s works are poignant—‘touching’. There’s an intimacy to their scale, their subject matter and its treatment. His preloved source images have passed through other hands, and are full of romantic intimations. His collage techniques emphasise his own hand, as he cuts into images with a blade and repositions them. The stress on touch is implicit in the results; say, in Marriages and Betrayals, where flesh meets flesh, and in the triptych, Touch (2015), where figures are beheaded to highlight where their hands are at, to make a point of body language.

Hands are crucial for Stezaker. He has a collection of found-object sculptures—vintage mannequin hands that rest on or grip small plinths. They offer a melancholy repertoire of rhetorical poses. He calls them Touch when they are palm down, Give when palm up (suggesting begging). These uncanny, disembodied hands—rescued from the past—recall those autonomous horror-genre hands with minds of their own, like Thing in The Addams Family and the vengeful severed hand in the 1981 film The Hand. Plaintive but creepy, they seem poised between life and death.

Death haunts Stezaker’s work. He says: ‘Death has been a central preoccupation of my thinking. There are often connections between fascination, death and the activity of being a collector. The found object can be seen as the death of the commodity and the collection as its mausoleum.’6 Stezaker also cross-references death and photography. For Camera (2015), he took a film still showing a group of men posing by a guillotine, as if having their photo taken. The condemned man just happens to be the tallest. All Stezaker does is to imagine that the photographer had composed the scene differently, by slicing a bit off the top of the still, beheading the condemned man prematurely. This gesture—combined with the title—promotes the looming guillotine as analogous to a giant view camera; its neck hole suggesting a lens. Like the guillotine’s blade, the camera’s shutter (or Stezaker’s scalpel) separates head from body, life from death, before from after. It’s a visual dad joke.

.

Stezaker is not a film historian. He knows little of the films in his stills or of the actors and actresses in his head shots. If he did, it would just get in his way. Not knowing means his source images can prompt his speculative associations and imaginative reveries. Not only are his sources conventional and repetitive, Stezaker takes pleasure in performing the same manoeuvres on them, over and over. On the one hand, this repetition could be owing to something insistent in his source materials, something in them he is uncovering and channelling, as if unable to escape their gravitational pull. On the other hand, it could suggest his own insistent, impressive turn of mind, purposefully projected onto his sources (repetition compulsion). Stezaker’s work sometimes has the quality of a recurrent dream, whose point nevertheless remains concealed or deferred.

This all raises questions about the artist’s agency. Stezaker often speaks as if his work involved putting his own interests and desires on hold, in deference to the inner life of his images, obeying their wills rather than exerting his own. He is, in his own words, ‘fascinated’—in thrall of his sources. He says, ‘images find me rather than the other way round’.7 He describes ideally working late at night, tired, lacking the energy to exert conscious control. And, he knows he’s finished a work when ‘I’m somehow not present. It’s there in front of me. It’s necessary, I see it, and that’s the end of it.’8 But, is this true or a cover story? Perhaps letting go consciously is just a way for your unconscious to get a grip. Believing the world is speaking to you when you are projecting your desires into it is the crux of fantasy—the world is asking for it. Of course, projection (or transference) is already a major theme in the works themselves—a conceit, then.

I can’t help but wonder about the gender politics. Stezaker cut his teeth as an artist in the 1970s, a time dominated by the rise of feminism and other critiques of ‘ways of seeing’. There was no escaping it. However, his source images hail from an earlier era, a pre-feminist time when gender roles were more constrained, when men were men and women women, and particularly so in the movies. His work is full of images of men and women playing their parts. Stezaker adopts an ironic attitude towards gender stereotypes, keeping them at arm’s length but also within arm’s reach, having his cake and eating it too. Affectionately revelling in and queering cliches, his work could be cast as a reaction to or an expression of feminism. Either. Both.

Stezaker makes his loving scalpel attacks on his orphan images, but he also rescues them from oblivion, redeeming them, keeping them in circulation. He gives them a second chance. He isn’t exactly retreating into the space of old movies (already a fictional parallel world, an escape) but forging a new fantasy space from its remnants. However, in our minds (and doubtless his), this new collage world and the old world of his source material remain inextricably entwined. His collages imply a perversity latent within his sources, even if it is a perversity he brings to them. Stezaker may cut and paste normative images from yesteryear, but they are no longer normative. They’ve outlived their authority and point. Through collage, he détournes them, reinvests in them, has his way with them, makes them dance to his own tune. He doesn’t so much discover a lost world as invent one, albeit in the guise of discovering it, disappearing into his image-world, becoming one with it.

It’s a marriage, but is it also a betrayal?

.

[IMAGE John Stezaker Mask CL 2010]

- John Stezaker quoted in David Lillington, ‘A Conversation with John Stezaker’, Collage: Assembling Contemporary Art (London: Black Dog Publishing, 2008), 27.

- Ibid.

- John Stezaker quoted in ‘The Third Meaning: John Stezaker in Conversation with Christophe Gallois and Daniel F. Herrmann’, John Stezaker (London: Riding House and Whitechapel Gallery, 2011), 37.

- ‘John Stezaker: Resonating Nostalgic Lyricism’ (video), Gestalten TV, 2013, https://vimeo.com/82096614.

- Laura Cumming, ‘John Stezaker: Film Works Review: An Overwhelming Onrush of Images’, The Guardian, 26 April 2015, www.theguardian.com/artanddesign/2015/apr/26/john-stezaker-film-works-review-de-la-warr-pavilion.

- John Stezaker quoted in David Lillington, ‘A Conversation with John Stezaker’, 28.

- www.mudam.lu/en/le-musee/la-collection/details/artist/john-stezaker-1/.

- ‘John Stezaker: Resonating Nostalgic Lyricism’.