Eyeline, no. 91, 2020.

John Stezaker has one foot in conceptualism and the other in surrealism, but his work is also a reaction to both. His deceptively simple collages generate complex sensations, thoughts, and feelings. Instantly appealing, they occasion lengthy unpicking—formally, psychologically. There always seems to be more to say.

The London-based artist says collage is about ‘stuff that has lost its immediate relationship with the world’ and involves ‘a yearning for a lost world’. He works from an archive of out-of-date images—mostly old film stills, old actor head shots, and antique postcards. These images come in standard sizes and are highly conventionalised—variations on themes.

Collage involves taking existing images, decontextualising them, reorienting them, cutting them, pasting them. But Stezaker may perform just one or two of these operations. Sometimes he cuts and pastes, sometimes just cuts, sometimes just pastes. Isolating these moves, highlighting the contributions they make, he foregrounds collage’s grammar and logic.

Stezaker’s exhibition Lost World has just been touring through Australasia. He talks to the curator, Robert Leonard.

Robert Leonard: Your work is an inquiry into the language and typologies of collage.

.

John Stezaker: That’s maybe part of what I do. I make three kinds of collage: image fragments, image subtractions, and image combinations. The fragments are the rarest, the combinations the most numerous.

My Underworld works are image fragments. I crop off the top thirds of film stills. They remain rectangular photos, but you can tell they’re fragments, because heads have been cut off.

Beheading was one of my earliest strategies, but, like most things in my work, it first occurred by accident and came as a revelation to me. When I cut the heads off an image of a kissing couple, I was after the heads, but I ended up with the bodies. I always think my best work is when I’m not so involved, when things happen by accident. My contribution is recognising that moment where things have escaped my intentions.

In film stills, the key information tends to be in the top third. Cropping them makes them illegible in narrative terms, and refocuses attention on minor characters and extras, settings, props, and so on. My Underworld works often feature children, who operate beneath the adult world, literally and symbolically. They occupy the pre-linguistic, preconceptual world of the image.

.

My favourite fragment is Camera (2015). In the still, the central figure is about to be guillotined. He’s also the tallest—the star. When you crop the still, you prematurely behead him. And the shape of the guillotine suggests a camera.

.

Camera was inspired by Daniel Arrasse’s book The Guillotine and the Terror. The guillotine and the camera are technologies that steal life. This analogy comes up over and over: the mechanical shutter and the mechanical blade. The arrested photographic moment has always been associated with death, while the guillotine has been called a ‘portrait machine’..

.

With the image subtractions—where you again remove part of the image—have a very different logic.

.

I wanted to find a way to create a deeper sense of incompletion or ruin, so I cut holes in film stills, subtracting the central object of attention. The image fragments are implicitly subtractive, yet remain whole rectangular images, but the image subtractions make the subtraction explicit, as an excised circle, a triangle, or a foreshortened rectangle. Georges Didi-Huberman writes about extras in films, who, in French, are called figurants. He says a figurant is not a figure, an appearance, but is there only to disappear behind the star. However, when I cut out the star, the figurants ‘appear’.

.

You subtract from images in different but specific ways.

.

With the Tabula Rasa series, the cuts are foreshortened rectangles. I started out thinking of them as blank canvases replacing subtracted figures, but a critic pointed out that they are like cinema screens, and I realised that there is some truth in this observation. I started to think of them as being like those overexposed cinema screens in Hiroshi Sugimoto’s photos. In my Circle series, the holes are like spotlights. In other works, the cuts are triangular, and emanate from eyes in the picture, like cones of vision or projector beams.

With the subtractions, the failure rate is huge, but that doesn’t worry me. In a given session, I might cut circles in half a dozen stills, and reject most of them. But, the failures can be reused, becoming apertures onto other images in my image-combination works. I invest in failure; failure guides me. But I need to have an idea first, in order for it to be subverted, to find another solution, another way. My work involves sacrificing images, but also redeeming them, resurrecting them.

.

You also use silhouettes as apertures, as frames.

.

This is something I’ve been doing since the late 1970s with my Dark Star series, and continued in my Shadow series. Later, in my Double Shadow works, I cut figures out of stills and placed them over other inverted stills. With film stills, the tops tend to be well-lit and the bottoms dark. So, by inverting the one underneath, I can emphasise the silhouette.

I’m fascinated with shadows and silhouettes. Pliny tells the story of Dibutades, who traced the shadow of her departing lover on the wall. She’s praying for his return—wanting his body to reconnect with its shadow—or lamenting his loss. The silhouette tradition has always been about remembering the dead. Silhouettes are visual prayers for their return, even if only in the imagination. In my collage Touch (2014), a cut-out silhouette—an absence—touches its shadow. I like the idea of absence connecting with absence in something tangible.

.

Where did your interest in film stills come from?

.

As a child, the cinema, particularly X-rated movies, was illicit—forbidden territory. I pored over the stills displayed outside cinemas. In the 1950s, there would be the latest colour feature, then a B movie afterwards. Those were the ones that really interested me. The B movies seemed to embody a shadowy underworld that I was desperate to engage with. Of course, it was terribly disappointing when I actually saw the films. I realised that the enchantment I felt was attached to the promise of the film still itself. Interestingly, you never got to see the stills in the film, as they were taken separately, by a stills photographer.

In the mid-1970s, the ritual of Saturday-night cinema was dying, because of TV and other things. Britain’s big Gaumont and Odeon cinemas were closing. Their informal archives of film stills, accumulated over decades, started to find their way into junk shops, which is where I found them. By then I already had a postcard collection and was making postcard collages.

When I began collaging postcards on film stills, it felt like an epiphany. In Negotiable Space 1 (1978), the film still shows a psychiatrist’s office—you can see the picture of Freud on the wall, the patient on the couch, and the psychiatrist leaning back, probably listening intensely to the patient’s dreams or whatever, and then there’s a postcard superimposed, with a train rushing out of a tunnel into the room, as if from the patient’s head—a Magritte reference.

That opened up a problem, because, in the late 1970s, at the height of conceptualism, surrealism was about as taboo as it could be. There was something clandestine about those early works with film stills—a private pleasure. I was keeping surrealism at arm’s length. I felt I hadn’t fully committed myself to it, but I was probing that area. I didn’t imagine for a moment that that work would still be going forty years later.

.

Uncanny temporal disjunctions occur when you collage much older postcards onto film stills and actor head shots.

.

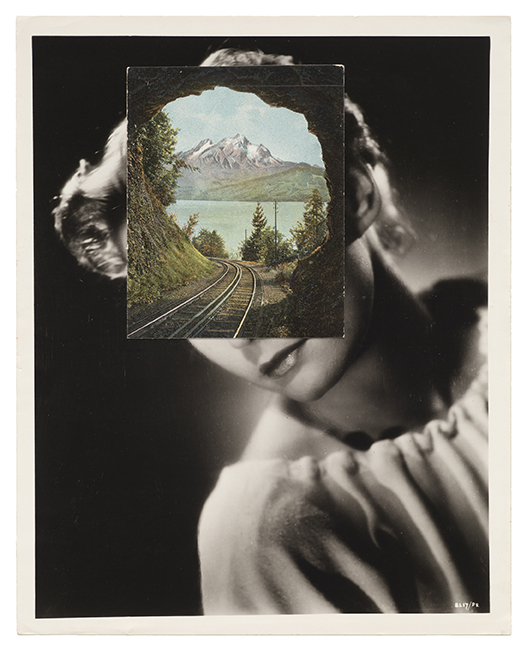

The average date of the film stills I use is somewhere in the late 1940s. I was born in 1949, so I think of them as parental images—images from just before my time. But, with postcards, I prefer colourised hand-tinted black-and-white photos from the pre-war period—grandparental images. Even though they are literally on top, I don’t think of the postcards as being in front. I feel they are excavating a space behind. Not only behind spatially, but behind temporally. Placing the postcards onto the film stills suggests a drift backwards in both space and time. It creates images of subjective interiority or that balance that Gaston Bachelard refers to as ‘a dialectics of inside and outside’—an ambiguity that can inspire what he calls ‘reverie’. A lot of the scenic postcards I use in themselves exemplify this reverie, featuring partial enclosures, ruins, forests, creeks, caves, and so on.

.

In your Masks, where you superimpose postcards on portraits, places on faces, the postcards add a dreamy element.

.

It’s amazing how little you need to make a viewer see a face within a landscape, or within any kind of amorphous figuration. It only needs to be a white dot to represent the eye or whatever. We are hardwired to see faces. There’s been psychological and neurological research into this, which suggests it is to do with how we’ve survived and evolved as hunter and hunted. Ernst Gombrich, the art historian, spoke about ‘the beholder’s share’, the way the viewer fills in amorphous shapes. A lot of my work exploits this.

There’s an uncanniness about masks. The face is a space of fluidity, flux. But, the fixity of the mask suggests death. The face is in perpetual movement, never still—until we get very old, when we become our own masks. When you wear a mask, your body is animated but your face is fixed, so masks are often to do with bringing back the dead, the animation of the inert.

.

A lot of your Masks use postcards featuring rocks or water.

.

In recent years, I’ve become interested in images of erosion: the relationship between flowing water and rocks. It’s invaded a lot of my works, particularly the Masks. There’s this ambiguity between stillness and movement, blockage and flow. Some Masks use postcards of waterfalls, which become veil-like. I like the idea of geological time invading the momentary image of cinema.

.

The Masks recall medical photos of faces eaten away—the opposite of the glamorous head shot. Was medical imagery important for you?

.

Medical images may have been the original inspiration for the Mask series. Many years earlier, as a first-year painting student, I had a small collection of obsolete medical manuals. I was traumatised by an image of a once-beautiful lady from the turn of the century whose face on one side had been consumed by cancer. It seemed incredible that she was still alive and capable of striking a dignified pose. That seemed to be the source of the uncanniness in the photo. I kept going back to it. As a painting student, I was wise enough to realise that there was nothing I could do with or to the image. I also found that Henry Tonks’s dignified portraits of facially disfigured soldiers, which mitigated their injuries, create more profound feeling of the uncanny than Francis Bacon’s more frontal expressions of horror.

.

In the Masks, postcards mask single faces, but, in the Pairs, they mask couples on the verge of a kiss. They mask relationships, concealing them and revealing them. They combine euphemism and exaggeration. The space between the lovers might be replaced with a country track, a torrent, a ravine, or a massive rock.

.

Since the 1970s, I’ve been working with ‘the kiss’. I don’t fully understand why I’m drawn to this image over and over, but it seems to have to do with its relationship with cinema. I like collecting images which are plentiful. You can always find kissing stills; there are lots of them. The kiss is even more ubiquitous in film stills than in films. It seems to be an image of cinema itself—the way cinema presents itself in still terms. The kiss is both a narrative consummation and a pause within the cinematic flow. It’s a euphemism for sex, but, equally, it is part of sex. Georges Bataille talks about the way that the sexes intermingle in the most intense way through the mediation of masks. The kiss seems to be an image of that intensity.

.

You play with gender a lot. In your Marriage works, male and female portraits are collaged to create new hybrid characters.

.

I like the idea of creating new personae out of the remains of existing ones. For me, my Marriage series is one of my most pleasurable. I can leave it for years and come back to it, and it feels like I’ve come back to exactly where I left off. It’s as if the whole series is preordained. Each time I start working on it again, it’s like dipping into a river. I have this sense of pure flow. I’m not saying it’s easy, but it’s instantaneous—you cut a face in half, you put it on another face, and a transformation occurs.

They work when they effectively suggest a real persona. There’s a slightly Frankenstein aspect to them. I often find portraits that match up seamlessly, but these don’t have the power to elicit empathy. The power is to do with disjunction and with where you align them. Some I align through the mouth, others through the eyes. Sometimes I produce a lot of Marriages at once. Some settle but most don’t—most don’t survive the night.

On one occasion, I completely ran out of head-and-shoulders portraits and found myself having to use three-quarter-length ones, that included hands, and something else happened, a different feeling, something more parodic, slightly comic. Crossdressers are often said to be betrayed by their hands, so I called them Betrayals. After all, betrayal is what comes after marriage.

.

Your works can be tender. They can also be violent.

.

In our culture, the incessancy of images is a violence we live with. There’s certainly violence in cinema: the movie camera developed out of the machine gun and celluloid comes from the munitions industry. I see my work as a tiny touch of violence to mediate a bigger violence—a homeopathic dose of poison.

I’ve spent a lot of my life teaching theory in art colleges, and I’ve often lectured on the relationship between trauma and the image. When I first saw Un Chien Andalou (1929) as a teenager, I didn’t realise the eye-cutting scene was faked. I thought it was for real. I don’t think I’ve ever been so traumatised by an image. The idea of blinding—a cut through the eye—stuck with me. The glossy surface of a photo is like the surface of an eye. In my Blind series, I ‘blind’ portraits by excising horizontal slivers across the subject’s eyes. I felt I needed to do it to exorcise the trauma. I’m not sure it was totally successful as I still find it difficult to watch this moment in the film.

.

Collage involves a dialectic of hurting and healing, rupture and repair.

.

Collage is about breaking up the world, but also carries the hope that it might be put back together. I relate to the Humpty Dumpty story. I always felt sad that he couldn’t be put back together again. Collage is a symbolic protest against this impossibility.

.

You’ve also been making movies from still photos. What does that add to the equation.

.

I’m exploring a dimension of image consumption in film which my collages and image fragments deliberately overlooked—the purgatorial, violent, and incessant qualities from which I was mostly trying to release the image. The films started out as an attempt to address the irredeemable qualities of the cinematic image but I am not sure that is what I achieved.

My first film was Horse (2012). I became interested in Giorgio de Chirico in the early 1970s. I travelled to Italy and started collecting images of equestrian statutes in profile, tiny little ones, with the idea of creating a de Chirico flip book, where the horses would move. But, it was completely unfeasible. It didn’t work at all. About a decade later, I came across the Stallion Annual, a book of stud horses, for those who want their mare inseminated by a champion race horse. On one page, you get the stallion’s form, all the races it’s won, and, on the other, a photo of it in profile. The book was a soft back, and the photos were identically formatted, so, when you flipped the pages, it was like a reverse Muybridge—instead of one horse being made to move, hundreds of horses were stilled. It took me another ten years to find a second Stallion Annual. Then, with eBay, I got the whole lot, and made Horse, with each image for one twenty-fourth of a second. I also made the film Cathedral (2013), using postcards of church interiors, each for a twenty-fourth of a second. It feels like you’re going in and out of a church.

So, in answer to the question—what do the films add to the equation?—I think it is more what they subtract. I think they are more about the absence of the image than the presence, about being caught between images.

.

You’ve also made films out of film stills, perversely re-animating them.

.

In Horse and Cathedral, there’s a recognisable central anchoring subject. Blind (2013) is different. It’s random film stills, each for a twenty-fourth of a second. I called it Blind because I made it blindly, not really knowing what would happen, and because we are supposedly perceptually blind to an image at one twenty-fourth of a second. But that turned out not to be the case. I expected a blur, but instead got an intense sense of the visuality of the image. When I first made Blind, one of my dealers said, ‘That’s wonderful. But I’m worried about all those swastikas.’ And, I said, ‘Swastikas?’ I got my assistant to go through however many images, and he found four with swastikas and took them out. Then my German dealer saw it and said, ‘Wonderful. Amazing how the nudity stands out.’ And I knew there was no nudity, whatsoever.

I characterise Blind as ‘cinema of discontinuity’—rather than enjoining us as viewers, everyone sees something different. Then, I realised that, every time I see it, I see something different. The brain takes in one or two images per second at most, so each time I see something different. So, not only is everyone seeing something different, everyone sees something different each time. Some people watch for hours to see every image, because eventually you do see every image, I suppose.

.

Crowd (2013) is a variant on this idea, using stills of crowd scenes.

.

With Crowd, I was trying to explore territory between the singular central image, as with Horse, and the chaotic multiplicity of Blind. My aim was to create the surging feeling of a crowd, but that didn’t happen. Something else happened, which was equally fascinating. It felt like a kind of white noise of the image, a bristling quality, like a crowd of crowds on the edge of perception.

It seems like a culture of images should be a culture of seeing, but it’s not. In our culture, images are overwhelming and reflective vision is almost impossible. With cinema, particularly, we never see a totality. We are always one step behind seeing. We chase the image but never catch up. We only have a partial sense of vision. In Crowd, there’s a couple of images I notice each time: a ship’s steering wheel and a hangman’s noose. Once I mention them, everyone sees them. I’m fascinated by the kinds of images that catch transient perception in this way.

.

[IMAGE John Stezaker Mask CCVII 2016]