(with Wystan Curnow) Art New Zealand, no. 95, 2000.

Legend would have it that Jim Allen was the prime mover in the development of post-object art in New Zealand in the 1970s, yet his story is absent from the history books and few examples of his post-object work are preserved in museum collections. One of the foremost New Zealand art educators of his generation, Allen visited Europe, the US, and Mexico for his 1968 sabbatical, returning with first-hand knowledge of new developments in art and news of student unrest. Under Allen’s leadership Elam’s Sculpture Department became a scene, a hothouse for experimental art. A tireless facilitator, Allen organised exhibitions and symposia, as well as making his own work. He also initiated international dialogue, bringing in visiting artists to teach at Elam and organising New Zealand participation in Mildura Sculpture Triennials and at the Experimental Art Foundation, Adelaide. In 1975, Allen crossed the Tasman and became the first director of Sydney College of the Arts, the renowned art school. Now retired, he returned to Auckland to live in 1998. That year, he installed a new version of his 1975 work Arumpa Road at Artspace, in Action Replay: Post-Object Art. Two of the exhibition’s curators, Wystan Curnow and Robert Leonard, talked to him.

.

Wystan Curnow and Robert Leonard: You did not begin teaching art at the tertiary level, but in the school system. How did teaching in primary and secondary schools inform your approach at Elam?

.

Jim Allen: When I came back from the Royal College in 1952, I was looking for work. Dick Seelye suggested I talk to Gordon Tovey, the National Supervisor of Art and Craft. Gordon was looking for ways to involve Maori in education and he’d already put energy into Gisborne and Porirua. Now, he wanted to extend an experimental approach to isolated communities. As I was not a trained teacher, I was appointed as a field officer and it was decided that I should work in the far north. With Bob McEwen, we selected three schools: Te Hapua, a school in a predominantly Maori community run by an expat Brit, George Ball-Gymer; Paparore, with a Maori head teacher and students of Maori and Dalmatian ancestry; and a sole charge school, Oruaiti, near Mangonui, taught by Elwyn Richardson, a brilliant teacher. Each school was quite distinct in terms of its community and the teaching set up. Almost all the children at Oruaiti came from the local Plymouth Brethren farming community. The Department’s Northland art advisors at the time—including Ralph Hotere, Katarina Mataira, Muru Walters, and Fred Graham—were pretty high-powered.

I spent the best part of six months at Oruaiti. Elwyn was a friend of Len Castle’s and Barry Brickell’s. He had already done considerable clay work with the kids, building impromptu kilns and firing things in biscuit tins, so they already had a background in clay. But I was able to show them different techniques and really push them. We built primitive keyhole kilns with twenty-four–gallon drums, lining them with bricks and laying them down in cuttings in banks. I remembered the Mexicans had built large terracotta figures by mixing bullrush seeds into the clay, which gave it high-tensile strength. We built enormous clay structures like that and had competitions about how high we could go without their collapsing. It was all a game.

One day, Elwyn and I were watching kids in the playground and thought it would be fantastic if we could bring the imaginative play and creative energy happening spontaneously there into the classroom. From then on, we more or less deliberately set out to re-examine each teaching situation in these terms. In essence, we connected activities, using one to reinforce another. Art making was linked to the three Rs and vice versa, with amazing results. It was an exploding chain reaction. Elwyn had the kids writing poems and producing magazines. I included examples in my reports to Tovey and they later found their way to Beeby, then Director-General of Education, where they were acknowledged with enthusiasm. Essentially Elwyn made it all happen. I was just a bit player.

I also did some secondary teaching at Northland College and Kaitaia College, where I was particularly challenged by a hard bunch of Maori kids, some fresh from borstal. There was no way of disciplining that mob, so it became a matter of channelling all their free energy. I got a lot of sandstone and pumice and we were chopping out figures and heads and animals with tomahawks. We made some incredible painted mobiles out of twenty-to-thirty-foot flitches from logs from the Totara North sawmill. The kids were great and we had a ball. In 1954 or 1955, I brought a truckload of our work down and filled the Auckland City Art Gallery. This was when Eric Westbrook was Director. He was very supportive and the exhibition seemed to make a big impression.

Not being a trained teacher, working with kids became a matter of sitting down with them, responding to them, treating them as real people, and showing them how to make the things they dreamed up. Nurturing, stimulating, and resourcing students—intellectually, emotionally, and experientially—that then became the basis of my teaching approach at Elam. My own training at art school in Christchurch had been craft-based—we weren’t encouraged to experiment or to take note of what was happening in the outside world. It was only after my time at the Royal College, London, and visiting major art galleries and museums in Europe, that I came to realise that ‘teaching’ could lead to gross inhibition and distort natural aptitudes. So, I quite consciously went the other way.

Subsequently, people have said I didn’t seem to teach anything, and this always pleases me. My effort went into creating a supportive environment, encouraging experiment and exploration, insisting that people find their own answer rather than providing them with one. I guess it was backdoor teaching, not leading from the front. I was always reluctant to tell students what to do.

.

At Elam, you pioneered the use of group crit sessions as a teaching tool. They were serious, with a tape recorder running.

.

The crit was a working forum, a closed group. It was just between us. It was based on trust, and, if anybody had broken that trust, it would have collapsed. It took time for a confidence to emerge, where we could really exchange. Students were forced to explain what they normally wouldn’t explain. And when you’re making art that’s important to you, you’re vulnerable. Some of it was pretty close to the bone. People like Bruce Barber could be hard on me or anybody else. It was tough. But, if you draw people together in a context of mutual respect, it can be like a battery; their proximity generating energy, shape, and motion. Nikos Papastergiadis uses the word ‘cluster’ to characterise this approach; ‘cluster’ indicating both the shape of people gathering and the process of their assembly.

.

What was Elam like when you were there, back in 1960?

.

The art school was in the process of formalising its relationship with the university. Paul Beadle had just been appointed head of school and a new building was on the way. Students had spent a lot of time drawing from plaster casts, but, during the move, the casts mysteriously ended up in Grafton gully. Afterwards, I thought that a bit precipitous, but it certainly helped to make a break. Also, as the prevailing attitude had been that students shouldn’t read books and that ideas were bad for them, there was practically no library. A librarian was appointed and a start was made in building up a collection. Serials were a priority, and, in a couple of years, the library was the place to go to for up-to-date information. By the 1970s, everyone was pretty familiar with what was happening internationally.

.

If you’d just been taught technique but not ways of thinking, going from the Canterbury’s art school to London’s Royal College in 1950 must have been difficult.

.

Traumatic. It was like I’d stepped out of the nineteenth century. I had some glimmerings of impressionism, but, beyond that, nothing. So, when I got to London, I was starting from scratch as far as contemporary art was concerned, and it was a struggle. Fellow students viewed my efforts with disbelief. It took eighteenth months and a total change of attitude to get to grips with my situation. There was a sense of excitement about the new directions sculpture was taking. Reg Butler and Lynn Chadwick were ahead of what was happening at the College. Eduardo Paolozzi had his first show while I was a student. When the time came to return to New Zealand, I was pretty well up with it.

.

In 1968, you went back on your sabbatical, the main purpose being to visit art schools in the UK and US. When you got to London, you contacted several expatriate New Zealanders—graduates from Elam and Canterbury—who had gone on to do post-graduate work at the Royal College: John Panting, Stephen Furlonger, Graham Percy, and Bill Culbert.

.

Yes. In fact, we stayed with the Pantings and others until we found a place of our own. By then, most of them were teaching in art schools, which was a great advantage for me. Furlonger was typical, teaching in three: the Central School in London; Nottingham, where Culbert had spent time; and Brighton. I was able to travel with them, sit in on crit sessions, and meet many of the staff and students. I spent about six months traveling around, visiting art schools. This also included sitting in on interviews for selecting new entrants. The rigour of the process impressed me; seven or eight staff quizzing each candidate for up to an hour, about their reading, then onto what art they liked and why, galleries they visited. It wasn’t kid-gloves stuff. They’d take issue, provoke arguments.

.

1968 proved to be a wild year, with riots, student protests, strikes, insurrection—if not revolution—threatening everywhere. How did these events impact upon your travels?

.

Well, I had renewed contact with Heinz Hengis, one of my teachers from my Royal College days, now teaching at Winchester. Back in 1951, he had taken a group of us through the still little-known Lascaux caves. He owned a small farm in that part of France, the Dordogne, between Les Eyzies and Montignac. When we caught up with him again, he offered us the use of it. We were there for a few months, did a lot of caving, and visited archaeological sites. The area had been lived in continuously for 30,000 to 40,000 years. Every creek contained ancient antler and reindeer bone and worked flints. Amazing. Next to our farm was a property owned by Harvard University, a permanent base for archaeology students. While we were there, Bobby Kennedy was shot. The staff and students were devastated. At the same time, we became aware that riots were taking place in Paris, and we began to think about getting out. Stuck in the countryside, it was hard to know exactly what was going on. The riot began with the students, but expanded into a nationwide critique of the repressiveness of Gaullism. The trade unions joined the students, the banks closed, there were food shortages, you couldn’t get petrol—all of France was affected. Parallel uprisings occurred in other countries. We had just enough petrol to get to a port, and, somehow, we got ourselves back to London.

As the authorities in Germany and France brought the uprisings under control, trade-union and student leaders, like Rudi Dutschke, refugees mainly from France and Germany, began to turn up in London. They set up camp in the old Crystal Palace grounds, drawing thousands of supporters to round-the-clock speeches around bonfires that were never allowed to go out. The Brits had their own problems. There was a nationwide revolt in the art schools over the Summerson Council’s hard-nosed approach to implementing the recommendations of the Coldstream Report, creating a new system of art education. There were funding cuts and art schools were finding it impossible to get accreditation. The action was not exclusively or even predominantly led by students. Much of the dynamism that sustained the movement came from the persistent grievances of staff, particularly part timers. There was great solidarity between staff and students. A good example was the last stages of the Guildford sit-in, where students were prepared to face imprisonment until they were assured staff would not be victimised. The ferment spread to the universities where there were sit-ins and twenty-four–hour open forums where all sorts of grievances were aired. The BBC was covering it all, moving from one hot spot to the next. These events were enormously instructive to me as they brought out into the open both philosophical and practical issues not normally accessible to an outsider.

.

What about exhibitions?

.

There was a major Henry Moore retrospective at the Tate. Royal College students tended to dismiss Moore, whose influence had been all-pervasive in Britain. It was an impressive show which included a lot of work that hadn’t been seen before, and it led to some well-informed discussions on his achievements. I was acquainted with two of his assistants, Oliffe Richmond and Alan Ingham, a New Zealand sculptor, and I was able to visit his studio. I met Moore later at the Tate, the first time since RCA days. There was a Takis show at the Arnolfini in Bristol. I also met Guy Brett, whose book on kinetic art I’d read in New Zealand. He invited Pam and me to his flat, where he still had most of the material he had gathered for his book, and we went through it together. This was my first acquaintance with South American work and the visit certainly stimulated my interest in Lygia Clark with her articulated metal sculptures, Mira Schendel with her knotted droguinhas, and Helio Oiticica, whose use of capes would have a direct influence on my Parangole Capes performance at Auckland City Art Gallery in 1974. His capes had deep pockets filled with tempera powder and the performers finished up with blue and orange arms and hands!

.

You were particularly interested in kinetic art.

,

Well, I was interested in everything. Guy Brett introduced me to the Signals Gallery in Wigmore Street, which featured such artists as Takis with his telemagnetic sculptures, Liliane Lijn, Jesus Rafael Soto, and the Philippine artist David Medalla. Auckland Art Gallery owns a typical Soto and one of Medalla’s bubble sculptures, both from this period. Signals Gallery was a focal point for Continental and Latin American kinetic art in the same way that Lisson Gallery gained a reputation for new and breakaway British sculpture. There were important shows at the ICA. Cybernetic Serendipity addressed the cross-pollination of art and science. Of course, back then, cybernetics was informing discussion around psychological and social processes, and it was very influential on my work. Another ICA show responded to the political upheaval in the British art schools, displaying documents and statements and providing a venue for debate. And I saw a lot of painting, of course. Marlborough Galleries were showing Graham Sutherland and Richard Hamilton. The Art & Language people were making their presence felt, and people like Panting and Furlonger were attracting attention with their brightly coloured fibreglass sculpture.

.

And they were very much in the forefront of developments in sculpture in the UK.

.

Yes, though it hadn’t been easy for them. Their work was known and respected within the fraternity, but acceptance by the London galleries was another ball game. The break came when their work was accepted by galleries in Holland, France, and Italy. They were exhibiting in places like Coventry, Brighton, and Nottingham, but, it was only after they had shown on the Continent, that the London galleries—Redfern, Lisson, and the others—picked them up. Bill Culbert showed at Lisson. He had just begun to deal with light. He was lighting perforated metal cans from within, projecting patterns of light and dark over the walls. The British had been much slower to respond to kinetic art than, say, the South Americans. Soto was attracting attention and Bill’s new work was part of a growing interest.

.

After London, you went to North America.

.

I flew to Boston around November. From there I went to Harvard, and on to Yale to meet Adrian Hall, at Graham Percy’s suggestion. They had attended the Royal College at the same time. I was very impressed by both Adrian and his work. At Harvard, I met art historians. It was quite hard poking my nose into these places, but I wanted to see what was going on. Then I went to New York, where I stayed for about three weeks. Peter Tomory was teaching at Columbia. Well, he was taking his classes in the park under the trees. The blood was still being washed from the steps of the University following the suppression of the recent student strike. Most of the University staff remained locked in their rooms, but Peter had elected to continue outdoors. Peter helped me to find my way around. He pointed me in Len Lye’s direction. I think Graham Percy may have done so also.

I had heard of Lye’s films when I was in England. So I went to Greenwich Village and found Len most welcoming. He gave me a lot of time. I don’t think he had seen too many New Zealanders in New York and my impression was that his connection with the country was very tenuous. He said something like I was the first person from the New Zealand art world that had ever shown any interest in him. He had been in New York a long time and was well-known and valued there. He had a studio loft at the top of his building. On a lower floor, his son had a workshop making furniture. While I was there, Len hooked up some wires and set a number of pieces in motion—I remember a great thunderous rolling piece, Storm King. I found out he had a brother in Auckland, in Birkenhead, not far from where we lived. When I got back, I looked him up, and, when Len visited in the following year, we had a bit of a reunion at his place.

Some of the art that sticks in my mind: Rauschenberg’s Revolver, large rotating screenprinted plexiglass discs, and Eva Hesse’s exhibition at Fischbach, with a number of small pieces incorporating latex on cotton that put me in mind of the South American artists—it was very different from anything else currently on show. From New York, I went to visit you, Wystan, at Rochester, and, if I remember correctly, on that day there was a student demonstration on campus! Right across America, I seemed to land in the aftermath of student demonstrations, but I never really came to grips with the issues as I had in the UK. That was mainly a matter of time, as I was constantly on the move. I was aware that some of the issues revolved around military research at the universities. From Rochester, I went to Buffalo, to the Albright-Knox, and then on to Chicago. There they were cleaning up after the bloody demonstrations and riots surrounding the Democratic Convention. Police bashings had prompted a protest exhibition.

Chicago was a complete surprise. Fantastic architecture—a vibrant place. I was impressed by the studios and student work at the Art Institute. The range of work and diversity of materials were amazing. They put me in mind of something that Tony Caro had said, back in the UK, that going to America had been a total liberation, that he always felt very inhibited in Britain because of art-school tradition, class structures, and critics’ and reviewers’ conceptions of what was acceptable. Such factors made it very difficult to work in an independent fashion there. In America, by comparison, artists just made things. After I returned to New Zealand, I realised that America had had somewhat the same impact on me as it had on Caro. I had never been to America before, and, in some ways, I was very critical when I was there. I had come through France and Italy, where there is an inescapable formality. America was something else! Some of the thinking was quite crazy, but that was part of the liberation.

.

Did you see that same liberation in the work that Adrian Hall was doing at Yale? Do you remember that piece of his with barbed wire and horse shit?

.

Yes, he bowled me over with that work. I saw it in a New York gallery. From memory, it was a metre-long glass box, which had a layer of fresh horse shit with short lengths of barbed wire mixed in. To say it was a powerful would be understatement. It focused my attention back onto the potency of materials as building blocks for ideas. I have Adrian to thank for that.

.

Of course, there is a great difference between Caro’s liberation and Adrian’s. For someone like you, brought up in such a strongly craft-oriented tradition, the liberation conceptualist-derived practices offered must also have been a challenge.

.

Well, I certainly had difficulty warming to Lawrence Weiner, for example, but I never had any problems with Hans Haacke. I guess that points to where my predilections lay. Remember, my craft orientation had been pretty well battered out of me at the Royal College, and, in between then and 1968, I had worked my way through some pretty strong idea-influenced experiences, the most potent being working with school children at Oruaiti and witnessing at first hand the power of the imagination released. The Royal College also taught me the danger of the closed mind.

I had seen performances at Arts Lab in London. I had been profoundly impressed by the work of Helio Oiticica, in particular a box poem. It was a small box. You had to open a door and inside was a plastic bag full of light-blue pigment. You lifted the bag, pulled it towards you, and a length of clear plastic with the poem printed on it unfurled. The poem was in memory of a friend killed by undercover police. Works like these turned my attention towards viewer participation. And, I guess for me, the power of conceptualism was that it provoked interaction between the viewer and the signifier in a way no other art form did.

.

On your return, you created environments—devices for processing the viewer, physically and conceptually. For instance, in your Small Worlds exhibition at Barry Lett’s in 1969.

.

Yes, for that show I created a set of situations. Everything was under UV light. Physically, viewers became part of the piece—their shirts and eyeballs fluoresced. There was a two-metre inflated PVC cube, and, next to it, a beard of thick nylon filaments, 100lbs breaking strain, with a channel down the middle you could walk through. Curtains of fine organza weighted down with fluoro tubes glowed as light was conducted through the fabric. And lead weights were suspended on fine nylon threads just below eye height, suggesting a horizontal plane passing through the space. And then, drawing on that Oiticica idea, there was a Hone Tuwhare poem, ‘Thine Hands Have Fashioned’, printed on strips of paper, which hung down, and you ran the strips through your hands to read it. The show filled the available space, so you moved from one situation into another.

.

O-AR Part 1 (1975) also involved reading texts.

.

We had Part 1 at Barry Lett’s, then Part 2 (also 1975) at Auckland City Art Gallery. The space at Lett’s was small and intimate, and I did my best to crowd it out. On the wall, I pinned typewritten texts that were fragmented—cut up. I’d played around with the texts a lot. The raw material came from a variety of sources, including kids’ writing from Oruaiti, wind-factor specifications for my Commonwealth Games piece, and extracts from books I was reading. On the floor were two sheets. On one was a stack of manuka stakes, on the other an arrangement of various shop-bought purpose-designed grids, plastic and metal meshes used in making concrete foundations, garden enclosures, or whatever. You could read ideas across the arrangement of meshes, between the meshes and the sticks, between the meshes and sticks and the texts, within and between the texts. I was providing information from which viewers could build relationships if and as they desired. I wanted to displace the normal paths of perception, leaving viewers to extract meaning from apparent near nonsense. It was hard on viewers, as there was no obvious answer. I was happy that it was a mess. It was an open situation. The work involved a range of information, appositional information. There was a dynamic between, on the one hand, the physical-spatial-material information, the objects on the sheets, and, on the other, the linguistic-conceptual information, the texts pinned on the walls. It was intended as a challenge to expectations of the gallery goer, not least of which being that this work was clearly not made to be sold.

.

A number of artists were using building materials as art materials, using them both formally and for their cultural resonances, Adrian Hall for instance. The two O-AR shows seem so different from each other.

.

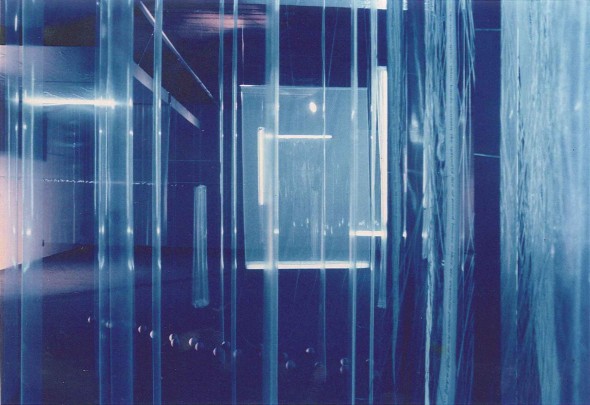

O-AR 2 was as different to O-AR 1 as the floor installation and the wall texts within 1 had been to one another. O-AR 2 was upstairs in two galleries at Auckland City Art Gallery. I really wanted to take charge of those barn-like spaces. Lett’s gallery was intimate, an inside-your-own-head kind of space, but here were bland open public areas, spaces to be walked through, with entrances and exits. They could so easily overwhelm a work.

If O-AR 1 was difficult and about cognitive processes, 0-AR 2 was about immediate physical processes. I was holding up a mirror to the presence of the visitor. Using long lengths of plastic hung ceiling to floor, I channelled people through the spaces. In one gallery, it was opaque, black, agricultural plastic, and, in the other, clear. Walking the lengths of the plastic created airflows that made them ripple, registering human presences. With the clear plastic, you could see the rippling and see the people through it, but with the black plastic only the ripple told you there was someone behind it. The viewer became performer, the performer the viewer. Black and white, yin and yang.

The only physical aspect that linked O-AR 1 and 2 was the grid forms: the meshes in 1 and the tiled gallery floor in 2. I like what you, Wystan, wrote in the Gallery Quarterly, talking about the title implying either/or and an oar—something that dips in, disrupts the surface, and propels you along.

.

The three performances in Contact (1974), another Auckland City Art Gallery project, were explicitly about social space, about restrictions, rules, parameters, scores. The performers and the audience were distinct. There was a social dynamic between the performers, but also one between the performers and the audience, sometimes kind, sometimes cruel.

.

The three pieces were very different. Computer Dance was noisy. There was the strobe light and couples, men and women, trying to ‘make contact’ using these infra-red emitters and receivers. It was difficult to come to terms with for audience and performers alike. Parangole Capes was slower, more humane. Four tightly bound performers rolling across the floor towards the centre, coming together, and, finally, helping set one another free. Then with Body Articulation, it really flowers. We covered the walls with plastic. The performers were instructed to start off by exploring their own body articulation by rubbing on paint and flexing, and then to extend their bodies in different directions. Most of them did that by lying on the floor and circumscribing movements with their arms and legs with paint. They spent a bit of time doing that as individuals, and then formed pairs to explore the physical relationships between two people, extending all their movements. People were picked up by the ankles and dragged around in big circles in paint. As Body Articulation progressed, the audience became far too enthusiastic and I was worried they were going to get their clothes off and get in amongst it. Seriously. And I thought if they did that, the Gallery would close it down. There would be a riot and that would be the end of it. It almost got out of control.

.

Contact was a social work. It not only involved a group of performers, it expressed a view about the difficulties (Computer Dance), the benefits (Parangole Capes), and the pleasures (Body Articulation) of relating to one another. So, it seems an opportune point to ask you about Three Situations, a project involving students from Elam and the Architecture School, assisted by industry, and captained by yourself. It must have been a major networking project for you.

.

It was 1971. Fletchers had been running this competition for Elam painting students for a couple of years, and Colin McCahon suggested they might widen their scope and do something with the sculpture students. They came to me with an open-ended invitation, and it was up to me to come up with some ideas. I’d been lamenting the shortage of materials available in the Sculpture Department and entertaining the idea of negotiating an agreement with a large-scale industrial concern, where they would supply materials in exchange for some kind of publicity. My students, David Brown, Bruce Barber, and Maree Horner were the core group. With Fletchers on board, we were able to do something on a scale we simply couldn’t have dreamed of otherwise. We had all sorts of discussions. Bruce Barber objected initially, being concerned that it was just an advertising thing for Fletchers, but he came around. We decided that rather than locate different works on a number of sites, we would work together to create a single major work, which would directly involve the public and respond to the site. We got the idea of creating three different sensory experiences, three linked ‘situations’, each large enough to walk into and through. First would be a two-level cubic wood and wire-netting structure. It would be linked to a quadrilateral pyramid, clad in silver foil, with an opening at the apex—for sunlight. Then, that would be linked to a large inflatable sphere, kept up by fans constantly pumping the air in. (When we came to do it, a tree was in the way, so we incorporated it as a centrepiece.) Much to our astonishment, the Council said okay. Fletchers supplied the materials. Working groups were set up. I handled the administration. The architecture students prepared plans, elevations, and specs, and made sure we could satisfy all the council ordinances. Maree and Adrian Hall, who was visiting lecturer, got busy on site, working with a construction team of students from architecture and sculpture.

.

Three Situations was aesthetically pushy, yet really populist. It dealt with things that people could understand easily. Light, space …

.

It proved incredibly popular. Bledisloe Place was a great site with huge pedestrian traffic, especially at lunchtimes, with thousands of people getting out of the office. Public response ranged from bemused tolerance to engaged participation. It was very successful. But Three Situations wasn’t just a one off. We organised Influx in Bledisloe Place the next year. There was lots of outside activity around that time—it was an outward thinking thing. We also staged events at the Easter Showgrounds. Phil Dadson was doing performances at Maungawhau, Albert Park, and all round the city. And, of course, we were making inroads into the Art Gallery too.

.

Making contacts was also central to your practice as a teacher. In the 1970s, you not only galvanised the students, you forged links with Australia. Soon, it seemed like there was an Australasian scene, with New Zealand participation in Mildura Sculpture Triennials and New Zealanders showing at Adelaide’s Experimental Art Foundation. Arumpa Road, the work you remade for Action Replay, was done first for Mildura in 1973. In fact, this was its first showing in New Zealand.

.

I participated in four Mildura Triennials, and it was gratifying that each time there was a larger New Zealand presence. Our channels for communication and transport to Mildura became so established that it was almost easier for New Zealanders to exhibit in Australia than for Aucklanders to exhibit in Christchurch. Arumpa Road was conceived exclusively for Mildura. Indeed, the title acknowledges the site in Mildura where I sourced the lengths of mallee timber I used—in forty degrees celsius! (The wood was similar to the driftwood used in the Artspace installation.) The work consisted of two wood piles in a vulvar formation. I put a twelve-volt car battery—the power source—in between, with leads running off to either end to metal stands situated clear of the timber. On one was an infra-red emitter and on the other a receiver. These were linked to a timing device connected to speakers buried in the bundles of wood, like ganglia. Anyone engaging with the work broke the beam and triggered a replay of radio news, commercials, topical interviews, etc. (At Artspace, it was the sound of the pedestrian crossing at the corner of Victoria and Queen Streets—people, cars, the buzzer). This racket came across in stark contrast to the organic heartland suggested by the wood.