Jacky Redgate: Mirrors, ex. cat. (Sydney: Power Publications, 2016).

Like many others, I first encountered Jacky Redgate’s work in Origins, Originality + Beyond, the 1986 Biennale of Sydney. Her work—Photographer Unknown: A Portrait Chronicle of Photographs, England 1953–62 (1980–3)—reproduced fifteen old snapshots as scaled-up art-museum-style photographs.1 The black-and-white images were a set. They shared a format and aesthetic and showed working-class people (mostly women, children, and babies). The title presumed they had a photographer in common, albeit unknown. Redgate subtitled the individual images, specifying locations and dates, but did not identify the sitters, although common locations suggested they could be related. We all assumed the pictures were not only by an unknown photographer but also of subjects unknown to Redgate.

Made in the wake of Roland Barthes’s 1980 bestseller Camera Lucida, Photographer Unknown appeared to celebrate vernacular photography, exposing the social ritual and iconography of the snapshot. (In the Biennale, it was positioned near Richard Prince’s work, which also appropriated non-art photographs.) Photographer Unknown made us into anthropologists. The images were evidence. They seemed to ask what we might learn from them, about their subjects and perhaps about photography itself. But apropos of what? Was class the issue here? Gender? Redgate’s scant entry in the Biennale catalogue offered little help and no backstory, just the obligatory quote by Marxist mystic Walter Benjamin—‘Every image of the past that is not recognised by the present as one of its own concerns threatens to disappear irretrievably.’2 In including the quote, was Redgate highlighting class concern or pointing to a more general sense of historical amnesia and loss?

In fact, it was all misdirection—smoke and mirrors. Redgate was not pro-remembering, but pro-forgetting. Years later, we would learn that Photographer Unknown’s sitters were actually Redgate’s relatives. The images had been taken over a time, from a few years before she was born to some years after, and all prior to her immigration to Australia in 1967. The images were found, yes, but had never been neglected. They weren’t discovered in some flea market or dumpster, but were family heirlooms passed on to the artist when she visited family in the old country in 1980. Photographer Unknown was, then, an autobiographical work in denial—but, perhaps, also one waiting for us to uncover that denial. In it, as Redgate would later explain, she considered herself an ‘absent presence’, a blindspot. It was as if she did not recognise herself in these images, herself addressed by these images.

Photographer Unknown was the work that first brought Redgate to public attention. It was a transitional one for her—the beginning of one approach, the end of another. Her earlier Adelaide art-school works had been freighted with personal history and metaphor, and leavened with psycho-sexual hijinks (at one point, the artist photographed herself naked frolicking with a chicken).3 They operated in a familiar feminist-surrealist vein and were presented in those women’s art shows that were de rigueur. One of the works even featured images later used in Photographer Unknown. That work, then, carried forward this personal subject matter, but depersonalised it, making strangers of family.

After Photographer Unknown, Redgate seemed to jettison anything explicitly autobiographical.4 The photographs and sculptures she would go on to make would be grounded in conceptualism and minimalism. They played on themes of appropriation and drew on arcane details from the histories of art, photography, science, mathematics, and window display. They were erudite—all about systems and logics. They often highlighted paradoxes that emerged in translating images and ideas from one medium, idiom, or dimension into another. These works seemed to make complete sense without any reference to Redgate’s biography or psychology. Gender was hardly an issue.

However, in the last ten years, Redgate has been revisiting her juvenilia, the personal work made prior to Photographer Unknown, drip feeding it into her shows, back into her oeuvre, while continuing to make new work. Why?

.

In 1959, in London, when Redgate was three-years old, she had a traumatic experience. While hospitalised for ten days with double pneumonia, she began to experience hallucinations. There were animals in her bed, and in the corridors and on the stairs of the ward. Little Jacky linked the visitors to aches and pains, often in her legs. After her release from hospital, the visions continued. The doctor asked Redgate’s mother to keep a diary, writing down everything her delirious daughter said, which she did, for months. Redgate’s suggestive comments—including ‘Pigs can’t get up sleeves can they mum?’, ‘Pigs can’t run as fast as nurses can they mum!’, and ‘He jumped up and put his black nose on my blue cardigan.’—were duly noted.

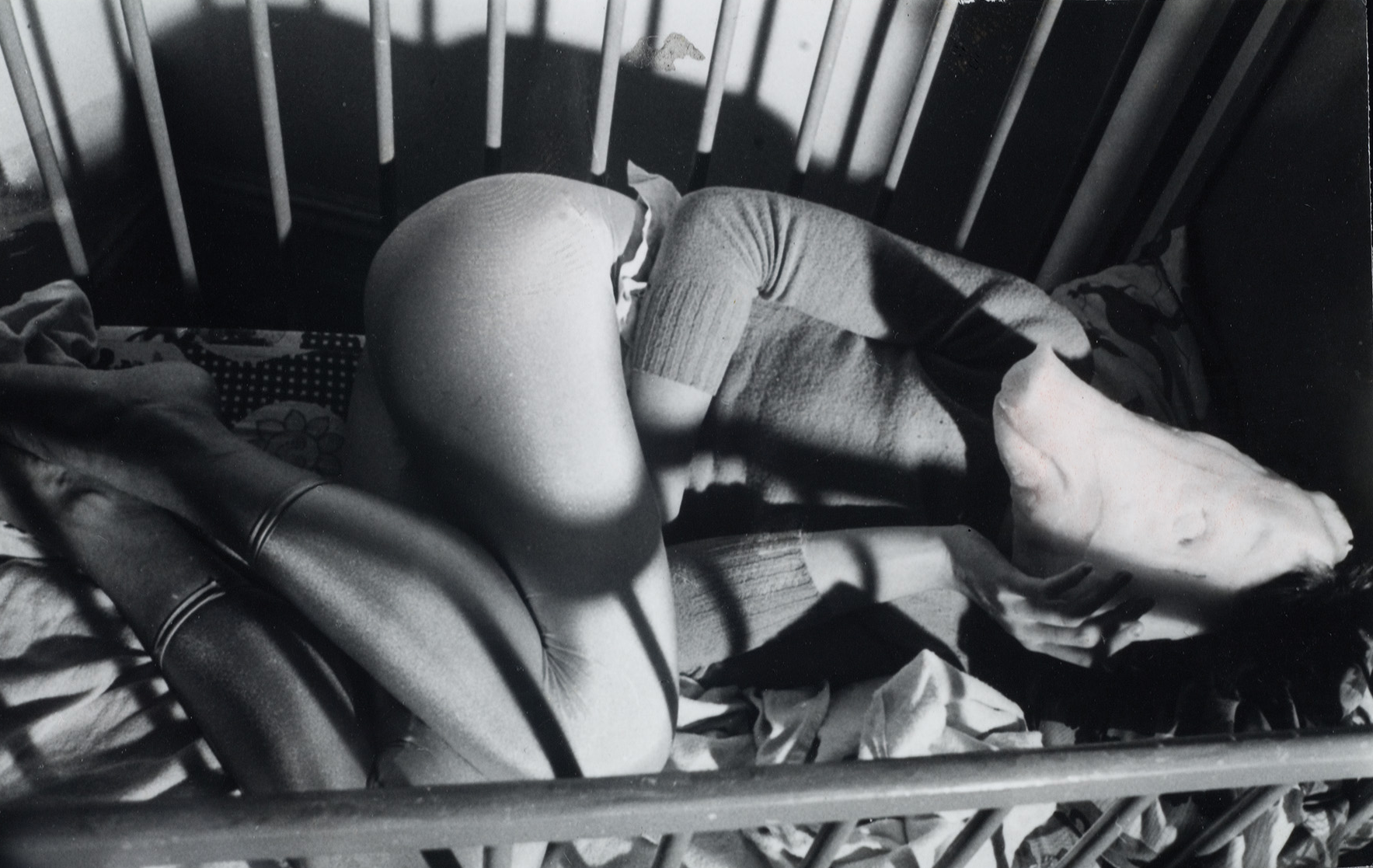

Twenty years later, in 1979, when Redgate was an art student, her mother gave her the diary. In the interim, Redgate had forgotten about the episode. The gift—which Redgate now calls, pointedly, the Mother Document (not the Daughter Document)5—prompted her to address this forgotten experience, not directly through memories (she had none), but indirectly, through her mother’s writing. That year, she made several works about it. Her hand-coloured photographic series, Untitled (Rosebud), featured her baby doll, Rosebud, in a cot, menaced by a wax pig’s head.6 Another photographic series, Untitled (Pig and Cot), included an image of Redgate in a foetal position in a cot, wearing shiny leggings and a wax pig’s-head mask (was she acting out her childhood issues in some regressive paedo-beasty psychodrama?). Untitled (Pig Tableaux) consisted of six surreal sculptures, each based on one of her inane infant remarks. One, inscribed ‘Pigs can’t get up sleeves can they mum?’, featured a pair of empty baby-blue wool sleeves anxiously gripped by two little wax hands. She also produced a ‘storyboard’ version of the Mother Document, with rubber-stamp illustrations. Then, in 1980, Redgate made a Super-8 film, Mother England, featuring some of those family snapshots that would soon resurface in Photographer Unknown.

All these works have now returned to haunt her—and us. Her 2005 survey exhibition, Life of the System 1980–2004, at the Museum of Contemporary Art, Sydney, included a photographic version of Untitled (Pig Tableaux). A satellite show, 1967: Selected Works from the MCA Collection, featured conceptual, concrete, minimal, kinetic, light, and other systems-oriented works made or acquired the year Redgate came to Australia as a ten-pound Pom. These works, which paralleled Redgate’s own later works exploring systems, perception, and space, were juxtaposed with a display of her immigration documents and childhood ephemera. Then, in 2008, in her survey show Visions from Her Bed, at Brisbane’s Institute of Modern Art, Redgate showed the kinky-piggy self-portrait, the rubber-stamp storyboard, and the Mother England film. The show’s title directed everyone towards these small unassuming works, as if, somehow, they were the crux of the matter—the source or vanishing point for all the ideas about vision that dominated her later work. In 2011, for her doctoral exhibition at the University of Wollongong, again titled Visions from Her Bed, Redgate exhibited a trove of childhood documents—including the Mother Document.

It seemed that Redgate was dredging up and reworking her early personal works and related documents to derange the coherence of her later impersonal work. ‘The return of the repressed’, they used to say. However, it was, of course, the mature (not the young) Redgate who was doing this, simultaneously making new-new work and new-old work. (Some of her revenant pieces were even given two dates: one for when they were originally made, another for when Redgate chose to reintroduce them, to entirely different ends.)7 Was Redgate genuinely conflicted or was this a gambit? And who were these sleeve-invading pigs, really?

.

Now, in Jacky Redgate: Mirrors at the University Art Gallery, University of Sydney, a show focusing on her apparently dispassionate mirror works, Redgate reintroduces another blast from the past. Miss Pears’ Contest Photographs March 1959 (2015) reproduces a pair of found photographs, portraits, taken in 1959, in the thick of her trauma period.8 Perhaps they were shot by her mother, perhaps not. Redgate can’t remember—again, photographer unknown. One shows the three-year-old Redgate; the other her reflection, her fraternal twin, Lesley. Both are naked. Each holds a Bakelite vanity hand mirror, presumably the same one. Neither sister looks into it. Lesley appears to be holding the mirror with her left hand, but, as they are both right-handed, Redgate suspects the image was flipped ‘for aesthetic reasons’. Pensive and demure, Lesley gazes out of her photograph’s frame, but not at us. Meanwhile, the precocious Redgate eyeballs us (or, at least, the photographer) coquettishly, with a touch of the Shirley Temples. Redgate’s proud mother quickly dispatched the images to a Pears’ Soap beauty contest, eager to win a prize.9

Times change. Although they doubtless appeared innocent in the day, these images of cute, big-haired, topless tots seem inappropriate now, especially in an art gallery. The Australian artworld is still reeling from ‘the Henson case’ of 2008, when Hetty Johnston’s allergic response to a risqué Bill Henson invite image almost brought the house down and caused the Australia Council to introduce strict guidelines for representing children in art. However, Redgate happily exploits her own image, made a half century earlier. She is surely alert to its problematic appeal. And, even if the image appears innocent, we know it to be attended by allegations of porcine molestation.

The image of Jacky junior holding a mirror seems prophetic, as if anticipating her mirror work to come. In this, it’s either uncanny or too good to be true. Redgate has made so many works with mirrors: Straightcut (2001–6), Edgeways (2006–8), Stonehenge (2008), and Light Throw (Mirrors) (2009–15). Mirrors have been an obsession. It’s the clearest throughline in her work. By introducing these baby photos into her oeuvre as a work, Redgate provides a wormhole: now mirror imagery links her least personal works to her most personal, prompting us to reread her mirror works through her earlier explorations of childhood trauma. Redgate asks us to rethink her mirror works not in optical terms but in psychological ones.

.

Straightcut encompasses around thirty images. Made over six years, it was a prolonged, obsessive enquiry—Michael Desmond called it a ‘campaign’.10 All Redgate’s subsequent mirror works elaborate on it. In it, she used a 4×5 view camera to photograph 1960s-ish modular plastic picnic-hamper-type items arranged in front of mirrors in a clinical white studio space. The resulting still lifes demonstrate optical illusions and perceptual dislocations achieved through hours of trial and error. Here, Redgate eliminates some key perspective cues and exploits others. She employs flat lighting and maximum depth of field, killing telltale shadows and making it hard to distinguish objects from their reflections. She aligns objects with their reflections; she shoots scenes at cunning angles, so reflections appear to be objects; she places objects against mirrors to confuse them with reflections and to block actual reflections; she shoots reflections and reflections of reflections. It isn’t instantly clear where things sit.

Back in the renaissance, Filippo Brunelleschi used mirrors in his perspective demonstrations, as he asserted the sovereign human subject as centre of the universe. Later, the camera obscura—a precursor to the photographic camera—would render the world according to this principle. But, the view camera Redgate uses doesn’t operate like this. Instead, it offers photographers the opportunity to confound perspective by bending the bellows, skewing the relation between the subject plane, the lens plane, and the film plane. This is normally done to correct for parallax, but, in Straightcut—as in her 1998–2000 photographic series Life of the System—Redgate uses it to derange perspective. So, despite Straightcut’s science-lab set-up, the sovereign observer is subtly displaced, leaving a psychological hole or blot where they should be.

Perspective is a two-way street. Centuries after Brunelleschi invented perspective, psycho-analyst Jacques Lacan saw a sardine tin bobbling in the sea and imagined it seeing him, witnessing him, and it embarrassed him.11 The sovereign viewer may fix the world, but, in turn, finds himself fixed within it. But, this isn’t really Redgate’s problem in Straightcut. Hers is not the horror of being seen by the sardine tin (or picnic hamper), but the horror of being invisible to it. Straightcut deranges the reciprocity between seer (photographer/viewer) and seen. Despite all those mirrors, neither photographer nor camera are visible. Standing in Redgate’s place, we might feel that the image isn’t returning our gaze, but that it looks past us, looks awry. She/we aren’t the projected centre of its world.

When we start reading Straightcut in psychological and biographical terms, everything changes. Those modular plastic picnic-hamper items once seemed to be innocuous and arbitrary subjects for Redgate’s perspective experiments. Now, they seem tied to the time of her childhood—like that Bakelite mirror—and to family activities. And, in her recent photographic series, Light Throw (Mirrors)—with lights bouncing off mirrors playing across a wall (Redgate’s bedroom wall, apparently)—Straightcut‘s precise optical games have been replaced by phantasmagorias and poltergeists. One imagines little Jacky, over-imaginative, over-tired, tormented by spectres.

.

Redgate’s recycling her toddler photo recalls another Australian artist whose work combines the impersonal and the personal, the system and the anecdote. In his work, Peter Tyndall made use of a photograph of himself as a small child, in which he stares intently at a building block. For him, this image took on a talismanic quality. It’s as if it already contained, in a nutshell, his life’s work, the world to come: ‘detail A Person Looks At A Work Of Art/someone looks at something …’. Tyndall explains: ‘My work seems to progress from one mysterious recognition to the next. Seeing this portrait for the first time in 1981 was one such important moment. Here, in a pose that normally might have been chosen by a portraitist to summarize a subject’s life’s pre-occupation, was just such a condensation at the beginning. Now this, my first formal posing, stretches out in front of me multiplied in apparently endless variation. It is as if the portrait photographer’s flash of light has fixed me forever in that 1952 moment of wonder … I also retain the fading proofs from the rest of that photo session in which I hold ducks and other toys with undisguised disinterest. This photo, the one my mother chose to have printed, was the only one with a block and with that look of wonder.’12 Incidentally, this quote comes from Tyndall’s 1992 catalogue, serendipitously titled Double Crossed Again: Death to all Mirrors!

Redgate’s and Tyndall’s uses of these arresting childhood images suggest prophetic pasts, futures foreshadowed. But, as much as the images are facts, they are facts in the service of fantasies. The artists, with the benefit of hindsight, have wilfully scanned their pasts seeking origins, and found them.13 What about all the other childhood images Redgate didn’t select, where she is not holding mirrors? And what of twin sister Lesley, also holding a mirror, who also became an artist, but not a mirror artist?

.

And, what about us? Is Redgate’s project solipsistic, with the grown-up Jacky staring into a metaphoric mirror, wondering what really happened to Jacky junior all those years ago? Or, is it addressed to us, her audience, as a ruse designed to make us consider our own interpretive process and projections, the conclusions we jump to—a tease? Is it about Redgate’s inability to reconcile things or ours?

Or, perhaps we could understand it as keyed to a wider art-historical trauma, typifying the moment Redgate came into the (art) world as the conflicted daughter of feminism on the one hand and minimalism and conceptualism on the other. Where minimalism and conceptualism resisted expressionism and suppressed psycho-biography, the women’s art movement clung to them. Which way to go? What’s a girl to do?

As Redgate’s work unfolds in successive exhibitions, her old personal work returns like a feral porker nibbling away at the coherence of her better-known, pedigreed minimalist-conceptual project. This begs the question: Is Redgate ultimately an artist of the system, as routinely claimed, or of its hysterical undoing? Stay tuned.

.

[IMAGE: Jacky Redgate Untitled (Pig and Cot) 1979]

- Photographer Unknown was made and first exhibited in 1983, but Redgate dates it 1980–3, from when she received the original negatives.

- ‘Theses on the Philosophy of History’, 1940.

- Chicken and Bride (ca. 1978), polaroid.

- One exception to this is the photographic series Untitled Day (1999–2000), for which Redgate reprinted old snapshots showing her family in backyards in London and Adelaide. It was made for the exhibition Warm Filters: Paintings for Buildings, Elizabeth House, Adelaide, 2000.

- Perhaps it’s because it was written by her mother; perhaps it’s because it was, itself, the motherlode.

- Was Redgate’s childhood doll really named Rosebud? It seems a too-convenient movie reference. In Orson Welles’s Citizen Kane (1941), Kane’s famous last word suggested female genitalia but actually referred to something innocent, a lost childhood sled. Redgate says Rosebud was the brandname of her doll.

- For instance, the photographic version of Untitled (Pig Tableaux) is dated 1979–2005.

- Photocopies of the original photographs were included in a document cabinet in Redgate’s doctoral show at the University of Wollongong, in 2011.

- Of course, in the Victorian era, Pears’ famously popularised John Everett Millias’s jailbait study, Cherry Ripe (1879).

- Michael Desmond, ‘Jacky Redgate’, Straightcut II (Sydney: Sherman Galleries, 2006), np.

- Jacques Lacan, The Four Fundamental Concepts of Psycho-Analysis (Harmondsworth: Penguin, 1979), 95–6.

- Double Crossed Again: Death to all Mirrors! (Berlin: Daadgalerie, 1992): 18.

- A more famous example would be Jeff Koons’s The New Jeff Koons (1980), a light box presenting a professional-looking portrait photograph of the artist as a child, looking cute but earnest, with an open box of crayons and a colouring-in book.