Victoria’s Art: A University Collection (Wellington: Victoria University of Wellington, 2005).

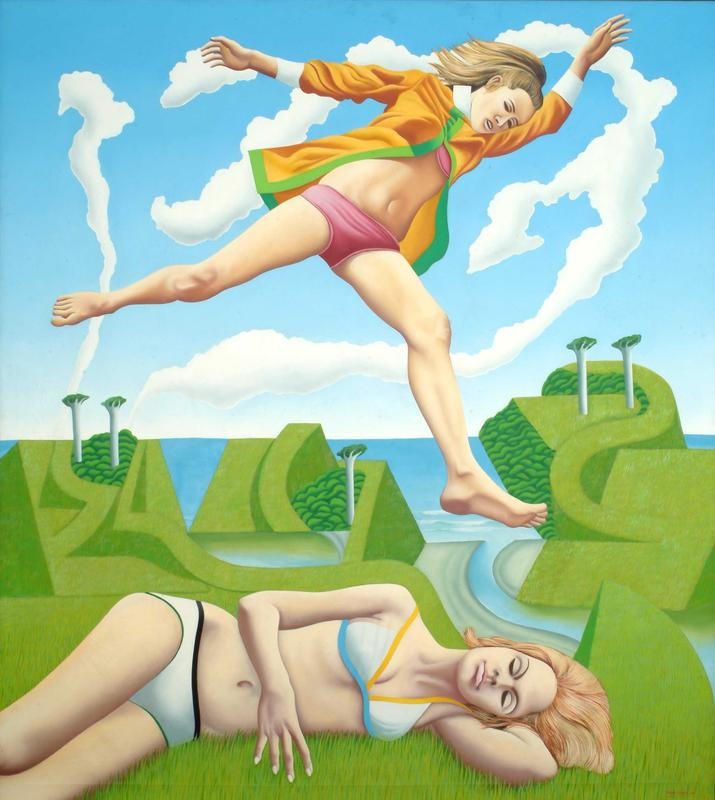

In the artworld, ideas come and go. Colin McCahon had a romantic-nationalist idea. He dreamt that he and his disciples might uncover the rhythms of their very selves within the landscape. It was a compelling idea, but also a difficult one. In the early 1960s, Don Binney filtered McCahon’s idea through a populist poster-art sensibility. His iconic images of birds frozen mid-flight over semi-abstracted New Zealand landscapes were feel-good McCahon, McCahon drained of existential struggle. Easy on the eye, they struck a chord with Auckland’s emergent art market, the bohemian bourgeoisie who lived in the suburbs but still wanted to identify with nature and had no time for McCahon’s heaviness. Then, along came Ian Scott. He was the next generation. He’d trained at Elam after Binney and under McCahon. Replacing Binney’s birds with dollybirds lifted from advertising, fashion mags, and men’s mags, Scott created iceblock-coloured pop-art Binneys, Playboy Binneys. Leaping through the air, flaunting their midriffs, or dozing in their knickers, Scott’s chicks could have been liberated modern women or pre-feminist sex objects. Their backdrop was clearly the wild West Coast—the mythic landscape celebrated by Binney. But it had become a stage-set, an abstracted landscaped landscape riddled with formal conceits and in-jokes—its geometry recalled the cubist letter-forms of 1950s McCahon. Collapsing the nature-culture dichotomy, Scott’s fantastic but inauthentic setting—inhabited by dwarf-phallic clip-art kauris and jism clouds—reeked sublimation. Scott exaggerated Binney’s cleaned-up view of nature, showing it up. While Binney images were intended as a celebration plain and simple, Scott’s Girlie Paintings were dark and complex. His nationalist-environmentalist-consumerist-swinger utopia—with its promises of emancipation—was haunted by a deep sense of control and repression. As New Zealand entered the 1970s, Scott attacked Binney’s paradise as an ideological blindspot. It was a turning point. It was pop.

.

[IMAGE: Ian Scott Jump Over Girl 1969]