Australian and New Zealand Journal of Art, 9, no. 1/2, 2009. Review of Hamish Keith, The Big Picture: A History of New Zealand Art from 1642 (TV series and DVD, Auckland: Filmwork, 2007; book, Auckland: Random House, 2007).

The Big Picture is billed as ‘a history of New Zealand art from 1642’, the year Abel Tasman discovered the place. Written and fronted by Hamish Keith, the six-episode TV series and its accompanying six-chapter book cover a lot of ground. They go from the art of first contact (and probably earlier, starting with prehistoric Maori rock drawings, ‘New Zealand’s oldest art galleries’) to current market stars, painters Bill Hammond (a Pakeha) and Shane Cotton (a Maori). Keith says The Big Picture is ‘a personal view, which is not to say that it is a subjective view’.

It is, indeed, a personal view. To understand what Keith’s doing you need to know where he’s coming from. He has been around a long time. He is probably best known as co-author, with Gordon Brown, of An Introduction to New Zealand Painting 1827–1967. Published in 1969, this landmark book popularised the idea of New Zealand painting as a search for national identity, embodying a view of New Zealand art that took shape under Auckland City Art Gallery Director Peter Tomory, for whom Keith worked as a curator. The book recognised landscape painters Colin McCahon, Toss Woollaston, and Rita Angus as the heart of modern painting in New Zealand, linking them to precursors in colonial-period landscape painting.

After publishing the Introduction, Keith went on to wear many hats. He wanted to move into politics, standing for Labour in Remuera in 1969. He left the Gallery the following year and worked at various times as an art consultant, newspaper art critic, broadcaster, and bureaucrat. He was national president of Actors Equity, founding president of the Writers Guild, Chair of the QE II Arts Council, and a board member (and later Chair) of the National Art Gallery. He became a celebrity, a staple of gossip columns, and was satirised on TV as ‘Beemish Teeth’. A dashing figure, Keith has been described as a raconteur, a boulevardier, a bon vivant.

In 1982, the Introduction was republished with an update chapter to fill in for the intervening years. It was not a wise move: the book needed an overhaul. Too much had happened since 1969 that questioned its central assumptions about the past. Within the painting mainstream, the modernist abstractionists had demanded a more international context for New Zealand art and sought to elevate the reputations of neglected pioneer abstract painters Milan Mrkusich and Gordon Walters. Also, distinct scenes had emerged for new kinds of art—post-object art, the women’s art movement, contemporary Maori art, and photography. Each of these ‘domains’ had issues with the limitations and blind spots of the New Zealand art mainstream, as represented by the Introduction, but, in the 1980s and early 1990s, all would be absorbed into it, fundamentally altering the DNA of New Zealand art. In the early 1980s, critic Francis Pound led the charge against the Introduction.1 When Pound published Frames on the Land: Early Landscape Painting in New Zealand in 1983, correcting the Introduction’s account of nineteenth-century New Zealand landscape painting (and, implicitly, the basis of the Introduction’s view of New Zealand’s modern art), Keith retrenched in defence of his earlier work, famously dismissing Frames as a ‘slim, pink book’, ‘facile and flimsy’.2 After that, Keith would not be hugely visible as a writer in shaping the discourse around contemporary New Zealand art.

Keith did, however, remain busy in art politics. He became Chair of the National Art Gallery, sat on the board that transformed it and the Dominion Museum into the Museum of New Zealand (ultimately to become Te Papa), and in 1999 convened Heart of the Nation, a government review into New Zealand’s cultural infrastructure. As a writer, however, he mostly penned social history and self-help books, and, on the occasions when he did surface as an art commentator, he exemplified the ‘curmudgeon’, tut-tutting curators and bagging the winners of the Walters Prize and New Zealand’s picks for Venice.3 In recent years, however, he has ‘returned’, interviewing photographer Christine Webster and painter Judy Millar for television documentaries, and now fronting The Big Picture. Native Wit, his autobiography, has just been published.4

The Big Picture offers a Te Papa-style account of New Zealand art: it is bicultural, essentially casting New Zealand art as a confrontation or conversation between Maori and Pakeha cultures5; it tracks changes in art against broader developments in New Zealand’s cultural history (aka ‘the big picture’); and it is insistently nationalistic, presuming art is best understood as national art. Keith takes a more-or-less chronological tack through six episodes, but flashes back and forth in time to make points, continually weaving in favoured artists like McCahon, Hammond, and Cotton.

The first episode, ‘The World Intrudes’, focuses on the art of first contact, starring the artists of Tasman’s and Cook’s voyages.6 ‘Engaging with Difference’ considers early Pakeha artists coming to terms with a different place and a different people. Starting with Victorian architecture, ‘Civilising’ centres on art’s role in creating a Pakeha New Zealand, but intercuts a parallel Maori story juxtaposing culturally radical Ringatu meeting houses of the late-nineteenth century with the cultural conservativism of the Ngata Revival of the early twentieth. ‘Reinventing Distance’ is mostly about an emerging Pakeha sense of national identity in art, involving rethinking our relation to Britain and Australia—an initial, crude, illustrative ‘New Zealandism’ being superseded by the big three: Angus, Woollaston, and McCahon. ‘In Search of the New’ starts with expatriates, including Len Lye and Frances Hodgkins, but ends up preferring the homespun modernism of McCahon and Co., bringing in the Tovey generation of Maori modernists along the way. ‘The Braided River’ attempts to open up the space of modern-to-contemporary art.

The Big Picture is entertaining, good-looking television. Keith is a charismatic front man. His distinguished persona is part Kenneth Clark, part Robert Hughes, part Sister Wendy. The publisher’s blurb for the accompanying book spruiks him as ‘our foremost art commentator’ and ‘our most eminent cultural statesman’—‘He’s seen it all.’ Keith hangs a lot on personal experiences, like horsing around with Pat Hanly at art school. He offers personal epiphanies—such as his decisive childhood encounter with Colin McCahon’s The Marys at the Tomb at the Canterbury Society of Arts—as justifications for his views. His anecdotes, haiku sound-bites, and throwaway judgements suggest we’re getting it all from the horse’s mouth. The problem is that The Big Picture is simply not that big a picture, especially when it comes to art since 1969.

The Big Picture may take a wider view than the Introduction historically and culturally, but much of it preserves the Introduction’s structure and emphasis, and Keith’s old biases are resolutely in place. Keith’s portrayal of New Zealand art’s early days may be rich and lively, but serves to bolster a conservative approach to recent art. His treatment of explorer-period and colonial-period art resolutely locks ‘art’ within ‘culture’ (social history and cultural politics). Keith still sets up artists as good and bad, winners and losers. The honest observation of colonial landscape painters like Augustus Earle and John Kinder is again celebrated, while foreign influence is anathema: William Mathew Hodgkins’s commitment to Turner was ‘wrong’. Art is still linked to a quest for national identity, albeit no longer just a Pakeha one, although McCahon remains the hero and crux of the story. Hanly is given a lot of airtime (which made more sense at the time of the Introduction, in which he got a whole chapter, not to mention the cover of the 1982 updated edition). Keith’s current-moment picks, Cotton and Hammond, who crop up repeatedly, draw on the McCahon idiom and are effectively positioned as McCahon’s heirs, implying that we are still essentially locked into a McCahon moment (or is it a Keith moment?). Keith seems unrepentant about his earlier neglect of New Zealand modernists, such as Milan Mrkusich, who is characterised as wearing ‘ill-fitting foreign clothes’. And while positive about the achievement of expatriates who left the country to seek modernism, he effectively reduces their significance to their expatriation, arguing their irrelevance to the New Zealand art story.7 It’s a shame Frances Hodgkins’s British works came back to New Zealand rather than remaining in the context in which they were made, depriving her of a place on the world stage, he argues. The real pity is that Keith didn’t take the opportunity offered by expatriates to construct a more complex post-nationalist art history. It would have served some of his key themes—the plurality of New Zealand art and New Zealand as a land of migrants.

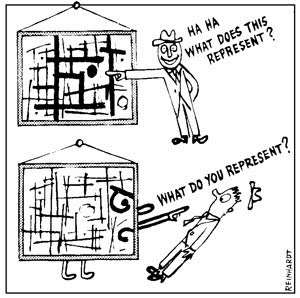

The Big Picture veers from a historical chronicle format to an argumentative essayistic one. Keith brings in all manner of stuff to make his points, but, behind this apparent richness, he sidesteps much of the art story. The Big Picture is ultimately richer in social history than art history. For all his celebration of art’s ‘braided river’—a self-consciously bicultural metaphor—Keith turns his back on the emerging complexity of New Zealand art after 1969, with the exception of Maori art, which is writ large. He mentions post-object art, but trivialises it, and does little to show its relevance in the current moment. Indeed, he satirises conceptual art generally by portentously deflating a balloon in an empty gallery. A couple of photographers are mentioned in passing, but the role of photography in shifting our art is passed over. And feminism never happened. Keith also has no time for the subsequent set of artistic sea changes that, for want of a better word, we call postmodernism. Apart from those in Maori art, he barely deals with developments in New Zealand art since 1980.

It could be argued that The Big Picture does not address recent art well because it is essentially historical in scope. However, I think it is really the other way around: The Big Picture is historical in order to neglect recent art, while nevertheless trying to shape tastes (and prejudices) about it. The Introduction used colonial landscape painting to provide legitimising precedents for the new, for McCahon and Co. Forty years later, however, The Big Picture asserts ‘history’ as ‘the big picture’ to neglect what is contemporary in contemporary art, nostalgically clinging to McCahon-era thinking. Interestingly, it seems the TV series commissioner may have initially been looking for a more contemporary approach. According to Keith, ‘There was surprise expressed that it was not going to begin somewhere vaguely in the 1950s’.8 Drawing a longer historical bow allowed Keith to heavily frame more recent art within a nationalist narrative and to shorten the amount of attention given to it. If he had started with the 1950s, Keith couldn’t have sustained his nationalistic argument over six episodes—the gaps would have been too obvious. (It’s worth considering that more art has probably been produced in New Zealand since 1969 than in all the time before.)

It’s easy to see The Big Picture as Keith’s attempting to redeem his discredited Introduction by reframing its late-1960s nationalistic painting-centric view of New Zealand art within 1990s-style biculturalism, keeping his canon intact by placing it within a wider and more relevant bicultural discussion about identity. Although ‘contemporary Maori art’ / ‘postcolonialism’ / ‘ biculturalism’—call it what you will—was once seen as delivering a fatal blow to the nationalist assumptions underpinning the Introduction, here it reveals itself as ally, a reason to retain rather than reject a nationalistic bias. While rightly questioning Pakeha assumptions about nation, biculturalism can’t see beyond nation, which is convenient for Keith. His rhetorical assertion of ‘the one simple fact that runs through all of this story’—that ‘the art made here or influenced by this place is the only art that speaks to us directly about our experience’—seems hopelessly retrograde. The idea of ‘New Zealand art’—an art made by New Zealand artists in New Zealand, shown in New Zealand galleries, purchased by New Zealand collectors and institutions, discussed by New Zealand critics in New Zealand journals, and about ‘us’—doesn’t have the traction it did in the 1960s. Our relation to the world has changed, as has the world’s relation to us. New Zealand artists no longer operate in a national situation. At all levels, they increasingly operate internationally, finding the stakes for their work in other places, other discourses.

Keith’s relation to ‘the international’ is messy. He condemns internationalists in their ‘ill-fitting foreign clothes’, but celebrates others who dig deep into ‘the stew’ of international art to make something (supposedly) their own. Milan Mrkusich is ‘still a bit too faithful to the European master Piet Mondrian’; Hanly, however—with his mash-up of the School of Paris, Francis Bacon, and taschisme—is celebrated as distinctly New Zealand. Keith’s argument frequently turns on such line calls. While arguing that the best New Zealand art goes its own way, Keith nevertheless pulls out overseas experts to validate McCahon—including Clement Greenberg, perversely, and a slide-talk audience at the Museum of Modern Art who were stunned by the appearance of speech bubbles in McCahon’s King of the Jews decades before pop!

Keith’s ideas have long been discredited in the New Zealand art world. The Big Picture appeals to a general public—one unversed in the critiques of Keith’s work and unfamiliar with the breadth of recent art—to keep his ideas in play. It is rife with score-settling. Keith is constantly dismissing other, often unidentified and unelaborated on, points of view. He creates straw men—trivialising the cultural-appropriation debate, for instance—so he can wade in like the voice of reason. He takes so many swipes at curating, bureaucracy, and Te Papa that a naïve viewer might assume he had not been involved in them. Keith characterises artists he likes as going their own way, against the dictates of fashionable theories and curatorial bandwagons, yet he has little time for artists who depart from his own values.9 Conflicted, he is happy to act as an authority when it suits, then attack ‘the establishment’ as fashionable and repressive when it doesn’t. When, after providing a textbook-bicultural account of New Zealand art, he attacks the very idea of biculturalism, it all begins to seem like a shell game.

Forty years ago, Keith was a player. He co-authored the Introduction at a time when nationalism was implicated in cutting-edge New Zealand art. Despite its biases and blindspots, that book engaged a broad public in the vitality of new art and ideas, and fostered an emerging scene. The Big Picture, by contrast, is the work of someone out of touch with art and defensive about it. In the closing episode, Keith prompts his viewers to visit galleries to witness contemporary art’s unfolding, but sadly it seems he cannot accept that the excitement he experienced in front of McCahon’s Marys today’s schoolboy might legitimately experience in front of, say, an et al. The pity is that, being such compelling and accessible television, The Big Picture will probably still be being used as a teaching aid in our schools in ten years time.

- Pound’s critique was effectively a mainstream one. He was concerned to elevate internationalisms within New Zealand painting. He had little care for the ‘domains’.

- ‘“Intolerably True to Turner!”’, Art New Zealand, no. 28, Spring 1983: 59. That year Keith published his own book on the topic, Images of Early New Zealand (Auckland: David Bateman).

- In her profile on Keith, ‘I’m Sorry, You’re Wrong’, Listener, 10–16 November 2007, Diana Wichtel called him a ‘proud curmudgeon’. Soon after, Keith began contributing a regular ‘Cultural Curmudgeon’ column to the Listener.

- (Auckland: Random House, 2008). Keith conducted the interviews for the Webster and Millar documentaries. Described as part of the ‘Profiles’ series, they add to the series of six half-hour TV ‘Profiles’ documentaries on prominent New Zealand artists Keith made with director Bruce Morison in 1982.

- Keith lingers on early paintings that depict bicultural meetings—Issac Gilsemans’s A View of the Murderers’ Bay, as You Are at Anchor Here in 15 Fathom, James Barry’s The Reverend Thomas Kendall and the Maori Chiefs Hongi Hika and Waikato, and Augustus Earle’s Meeting of the Artist and Hongi at the Bay of Islands, November 1827—to set up this idea.

- For clarity I have used the book’s chapter titles. The TV episodes are not individually titled.

- Here, however, he also hedges his bets, pointing to a self portrait Barrie Bates—soon to become Billy Apple—made in London, where he sports a moko.

- Email to the author, 5 January 2009.

- While he champions the ‘ferals’—Tony Fomison, Philip Clairmont, and Allen Maddox—for operating outside fashionable theories, Keith neglects to mention how hugely fashionable they were in their day.