Grey Water, ex. cat. (Brisbane: Institute of Modern Art, 2007).

Beatrice Page interviews curator Robert Leonard.

.

Beatrice Page: Grey Water is a topical title. The drought has been so pronounced here in Queensland. All the nurseries and gardening-supplies shops have closed down because no one can water their plants anymore, and everyone is talking about how they can reuse their ‘grey water’. I’m reminded of General Ripper in Stanley Kubrick’s film Dr Strangelove. He ranted on about maintaining the purity of his precious bodily fluids.

.

Robert Leonard: Yes, Ripper triggered doomsday because he thought fluoridisation was a communist plot. It’s certainly been interesting researching the show and finding out what a key role water has played in war. It’s fascinating how many wars have been waged over water and how access to water has been crucial in determining the outcome of conflicts. In the developed world, we’re water-rich. We use more water than people in developing nations. The average American consumes something like 2,000 cubic metres of water per year! With population growth, though, the amount of drinking water available per capita is decreasing. Much of the conflict in the Middle East is over water, with Israel, for instance, controlling 80 percent of the Palestinian water supply. Today, 40 percent of the world’s people have inadequate water and millions still die every year from the effects of contaminated water and drought. Some say clean water will be the next oil, but perhaps it already is.

.

There’s definitely an economic dimension to the show: contrasting the haves and the have-nots.

.

That is really apparent in the way Zhang Huan’s video and Roland Fischer’s photographs echo one another. Fischer’s two photos are big-budget fine-grained portraits of well-heeled women in LA, exquisitely made up, posing in water, staring at the camera. The women look glamorous, as if they are in cosmetics ads. Huan’s performance-for-video To Raise the Water Level of a Fishpond, on the other hand, features a bunch of men, disenfranchised migrant workers in China, people from the bottom of society. On an overcast day, they walk into a fish-breeding pond, and stand there motionless, facing the camera. Huan joins them, carrying a young boy on his shoulders. The participants are dispersed, disconnected, suggesting alienation, resignation, futility—as if they could really ever significantly raise the level of the pond just by climbing in. But, like the women in the Fischers, they seem to be at peace. There are local references in the works of both artists: the Fischers were shot in LA, the city of swimming pools, while Huan draws on Chinese tradition, where water represents the source of life and fish represent sex. Fischer hones in on women, Huan on men; Fischer on individuals, Huan on a whole class. But the similarities are uncanny. Both works seem so idyllic, meditative, and ‘universal’.

.

Well, water is a universal thing, but, like most universals, what’s interesting is the myriad of different ways its universality is played out—politically, economically, and culturally.

.

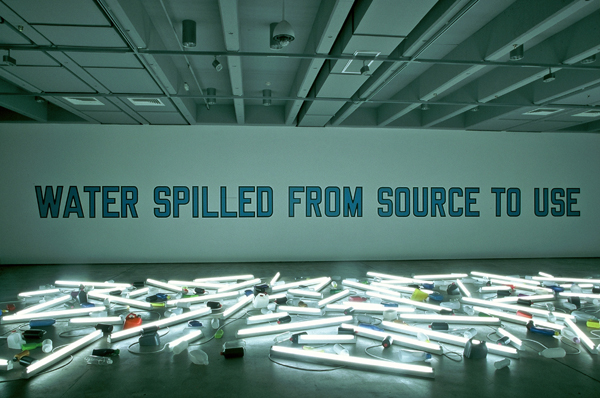

People’s different relationships to water point to other differences between them. This interplay between the generic and the specific is a subtext throughout Lawrence Weiner’s work. He exploits the generic quality of language, the space between words and what they describe, the fact that one phrase can have a number of quite different references. On the wall, he writes the words ‘WATER SPILLED FROM SOURCE TO USE’ in an authoritative, no-nonsense typeface, on the scale of signage or advertising. It could refer to me taking a shower this morning or to the massive redirection of rivers for irrigation or power generation. It could refer to Third World women required to carry water from rivers and wells to their homes or General Ripper diluting his grain alcohol with rainwater. In imagining what the text refers to, Weiner makes us confront a generic-universal dimension and a specific one.

.

Rosemary Laing certainly relishes the dystopian angle in her Remembering Babylon photos. These lovely scenic photographs recall a terrible past or envisage a horrid future.

.

Bald, disembodied heads lie in and around a salt bore somewhere in the middle of Australia, suggesting the hubris of early explorers of the Australian interior who died of thirst. Right now, it’s hard not to look at these pictures and think of a dehydrated future Australia, where we are fated to die in the last pool of our own dirty water. I like the way the Laing works speak to Abie Jangala’s Water Dreaming painting. Jangala was a senior Warlpiri rainman. The central motif in his painting is a soakage surrounded by water courses, and on either side there are representations of thunder and lightning.

.

The show tackles water as metaphor and material, and the traffic between them. A couple of works are particularly focused on the physical qualities of water.

.

Yes, like Lawrence English and Toshiya Tsunoda’s ambient sound work Bathe, playing in the foyer, consisting of hydrophonic field recordings. They sampled the sounds of water in various states of motion from locations in South-East Queensland. (I find the piece rather corporeal. The first time I heard it, I thought I was listening to my own internal gut-gurgles.) Like air, water is an inherently silent medium. It needs to be agitated by external forces to make any sound. English and Tsunoda are interested in the way water gets ‘coloured’ by this process.

.

That links with Marian Drew’s photograms of agitated water. We think of water as ideally transparent, but she records its shadows.

.

I love the way her images capture the swells, ripples, and eddies of water. Her process is interesting. Drew placed massive lengths of film in a bath, under water. She agitated the water and exposed the film. She contact-printed the negatives, creating actual-scale images. Unlike a photogram of solid objects, a photogram of water looks similar to a photograph of water, and I guess that’s the point. For me, the process seems to refer back to the pre-digital processes of ‘wet’ photography, where sheets of light sensitive paper are processed in baths of diluted liquid chemicals under constant agitation.

.

There’s a lot of death in the show. Teresa Margolles’s work is so heavy.

.

Margolles’s art has its origins in her work as a forensic technician in a morgue in Mexico City, where she witnessed the social and economic circumstances of her country reflected in the state of corpses. She saw victims of drug addiction and violence, and large numbers of anonymous dead bodies. She says she’s interested in ‘the life of the corpses’, the fate of the bodies after death. She’s used the water used to wash down corpses a lot. For instance, she has used it to hydrate rooms, creating a mist you walk through and breathe in, that gets in your clothes and into your lungs. In the Air, the piece we are showing, was the first Margolles work I ever saw. It was in her big show Muerte Sin Fin at the MMK in Frankfurt in 2004. The atrium was empty except for a couple of soap-bubble blowing machines up high. Bubbles were pouring out and slowly descending to the floor. People were walking through them, playing in them. It seemed frivolous and delightful—a bit disco-like. Then I went up to read the label and it said the bubbles were made from morgue water. It became chilling. The piece plays on the familiar image of soap bubbles in old vanitas still-life paintings. In that era of high infant mortality, soap bubbles stood for the frailty of human life.

.

The Peter Greenaway work is also about morgues and water.

.

Greenaway has always been obsessed with water. It is a kind of leitmotif throughout his films. We’re showing his 1988 made-for-TV short film Death in the Seine. It was inspired by Hippolyte Bayard’s famous early photograph, a self-portrait where he pretends to be a drowned man. Greenaway’s film draws on records made by a pair of Paris mortuary clerks at the end of the eighteenth century, the years following the Revolution and the Terror. They recorded, in a pedantic yet haphazard way, details regarding hundreds of cadavers fished out of the river Seine. In most cases, the cause of death—accident, misadventure, suicide or murder—was either not known or not recorded. A portentous voice reads from and comments on twenty-three of these accounts, as we watch bodies being retrieved, washed, labelled, and arranged for view. At the end, we see the bodies twitching, and it’s obvious these are actors playing dead, just like Bayard.

.

But what’s he saying about water?

.

Well, that’s the thing. All the action circulates around water and watery imagery, and water is shown to touch these people’s lives and deaths in all manner of ways, but its ultimate significance is left hanging—it’s an open question.

.

Roni Horn is equally informative yet evasive in her work Still Water (The River Thames, For Example), a set of photographs of the dark, dirty, turbid water of the river Thames.

.

It’s another archive-style piece. Horn’s images of chaotic waters are speckled with tiny numbers, like footnote references. And beneath the images, like legends on maps, are the numbered notes. These unsourced texts are a medley of Horn’s own writings and excerpts from other sources, including newspaper reports and forensic archives. It’s like the Thames is polluted literally but also metaphorically: it’s freighting too much history, too much symbolism. And yet somehow the river always remains ‘other’, even to this content. Horn said: ‘In these images you see how unfamiliar water really is. Perhaps because it’s so complex, one of the qualities of water is to sustain this unfamiliarity.’ She asks that the individual works from the series be installed in different spaces so you can’t ever see them together, frustrating your ability to compare, stretching your memory.

.

More hubris. It’s as if Horn were trying—and pointedly failing—to map the unmappable, the relation between human consciousness and water.

.

Water as a mirror—as an inscrutable screen for the projection of human psychology—is a consistent theme. I like the Andrei Tarkovsky sci-fi film Solaris. Men in an orbiting space station are studying Solaris, a planet covered with a mysterious, conscious ocean. As they probe it, the ocean responds by confronting them with their most painful and repressed thoughts and memories manifest in material form, laying bare their personalities while revealing nothing of its own. It is hard to know if Solaris is benevolent, or diabolical, or neither.

.

Jun Nguyen-Hatsushiba is a Japanese-Vietnamese artist known for filming underwater performances as poetic ‘memorials’. The density and darkness of the water, and its effective lack of gravity, give his performances an otherworldly quality.

.

His work in Grey Water addresses a famous eco-disaster. Nguyen-Hatsushiba shot his film in Minamata. In the 1950s and 1960s the Chisso Corporation released mercury-contaminated waste water into the sea at Minamata. More than 1000 local residents died horrible deaths, while tens of thousands suffered chronic blurred vision, slurred speech and fetal deformity. The film intercuts images of one of his underwater performances with images of children playing in front of a factory, a quiet harbour with fishing boats, abstract orange swirls in water (perhaps an oblique reference to America’s use of the herbicide Agent Orange during the Vietnam War), someone resting on a bed (perhaps convalescing) and kids at a dance party. The performance itself takes place in a coral reef populated by barefoot scuba divers in swimming trunks. They link hands within a geometric Plexiglas enclosure. The work implies social interdependence, community, remembrance, healing. It’s a rather whimsical treatment of a heavy topic.

.

The centrepiece of the show seems to be Bill Culbert’s massive floor piece Flotsam. It embodies contradictory feelings about water.

.

It’s aestheticised pollution. There’s a sea of lit fluorescent tubes interspersed with empty plastic bottles; some coloured, some not; some transparent, some opaque; some marked ‘poison’. Though the labels appear to have washed off, most of the bottles seem to be of the types used for cleaning fluids. Culbert calls them ‘janitorial’ materials. You can read the fluoros as the water that the bottles float in it, or see them as part of the litter floating on the water.

.

To me, Flotsam is a sublime landscape, glowing like Caspar David Friedrich’s famous painting of the sea of ice, only it is a sea of pollution, detritus from consumer culture—so I guess it’s more a technological sublime. Formally, it goes beautifully next to the Jangala, with its shimmering luminosity and imagery of lightning strikes.

.

The decorous overall effect comes from the play between the brilliant linearity of the tubes (three different lengths), the arabesques of the power cables, and the accents of the bottles; all evenly dispersed. It recalls the rhythmic fractured space of analytic cubism or the decorative all-over fields of Pollock. Culbert’s Flotsam is a fabulous mixed metaphor. The work plays on the paradox that cleaning products are toxic, that cleanliness is polluting, not only the empty bottles but what was inside them—all those chemicals washed down the sink and sent out to sea. Flotsam may suggest the polluted and toxic, but it is so clean and luminous, so pleasing and harmonious.

.

It’s like the old adage: nothing is more artificial than purity.