Art and Australia, vol. 44, no. 2, 2006.

The Asia Pacific Triennial always offers a particular slice of New Zealand art, prioritising Maori and Pacific Island work and work engaged with matters of cultural identity. So, when I hear New Zealand pioneer abstract painter Gordon Walters (1919–95) is being showcased in the new APT, it gives me pause. It makes no sense and it makes perfect sense. Walters has had the luck—good or bad—to find his work caught up in a series of paradigm shifts in New Zealand’s art and cultural history. This, as much as the indisputable excellence of his work, has made him New Zealand’s highest-rated modern artist after McCahon. As the purest formalism, Walters’s work was never addressed to cultural politics and really has little to contribute to them, and yet the work has become so embroiled in cultural debates that now it’s hard to see it in any other way. It comes to us freighted with all it is not. How did this happen?

When Walters starts out, there isn’t much of an art scene in New Zealand and little engagement with modernism. Walters’s long-distance relationship with modernism is nurtured by his friendship with émigré Indonesian-born Dutch artist Theo Schoon, who he meets in 1941. Schoon, who did his art school in Rotterdam, fosters Walters’s growing appreciation of modernist painting. He also shares Walters’s interest in Maori art and encourages him to introduce indigenous elements into his work. Unlike most New Zealand artists of his generation, Walters travels. In 1946, he visits Sydney and Melbourne, making contact with Charles Blackman, Grace Crowley, and Ralph Balson. In 1950, he spends a year in Europe, checking out modern art in the flesh. At the Denise René Gallery, in Paris, he sees the geometric abstraction of Auguste Herbin and Victor Vasarely, and, in the Netherlands, he enjoys Mondrian and Co. Returning to Melbourne in 1951, Walters produces his first non-figurative works, before heading home in 1953. Over the next decade, Walters’s work riffs on modernist abstraction, Maori and Pacific arts, and a folio of intriguing drawings by Rolfe Hattaway, a diagnosed schizophrenic at the Auckland asylum where Schoon worked as an orderly in 1949. Walters’s designy hard-edged abstractions declare his abiding interest in figure-ground ambiguities.

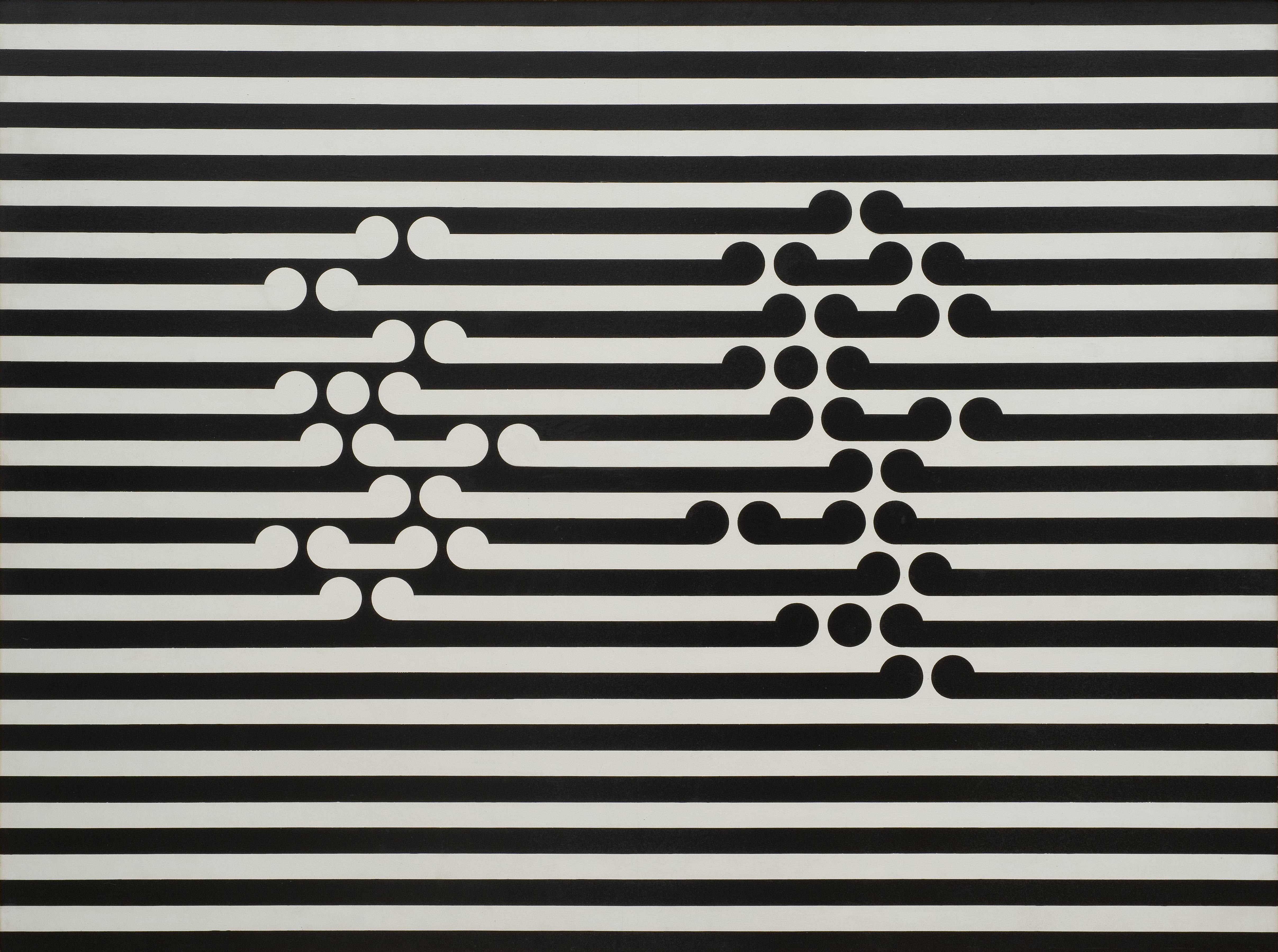

In 1956, Walters starts exploring the koru, the curving bulb form from Maori moko (facial tattooing) and kowhaiwhai (meeting-house rafter paintings). Through a series of studies, he Mondrianises the koru, straightening and regimenting its scroll-like forms; taking it from organic to strictly geometric. His version of the motif consists of lines and circles: alternating horizontal stripes of equal width with circular terminations, the circles two stripes wide, extending upwards.1 Walters’s koru recalls the Chinese yin-yang symbol, in which dark and light mutually invaginate, each equally figure and ground. Paintings follow. The first is Te Whiti (1964). Walters makes Koru Paintings regularly through into the early 1980s, when he largely exhausts his interest in the possibilities of the form. All the time—before, after, and during—he produces other non-koru works, but the Koru Paintings will become his trademark.

Walters’s oft-quoted rationale is: ‘My work is an investigation of positive/negative relationships within a deliberately limited range of forms. The forms I use have no descriptive value in themselves and are used solely to demonstrate relations.’2 Despite their restricted language, there’s huge and subtle variety in the Koru Paintings. Some are sedate, others jaunty; some are assertively flat, others push out into three dimensions. Walters discovers and explores all manner of effects through varying, for instance, the proportion of the stripes, the density and orientation of the circles, the size and shape of the support, and the colour scheme. (While the Koru Paintings are typically remembered as black and white, Walters actually engages a variety of contrasts of tones and hues.) With their uninflected surfaces and precise geometries, the Koru Paintings might seem cool and mechanistic. In fact they are highly intuitive, with Walters adjusting paper collage mock-ups to determine his compositions seeking an ineffable rightness.

The Koru Paintings have much in common with the contemporaneous op art of Victor Vaserely and Bridget Riley. They are phenomenological. They play on the way we see; they test our ability to map them. The compositions are organisations of tracks and gates for channeling vision. They have an implicit grid: the lines providing the horizontal element, the circles the vertical. Our eyes scan the lines, coming to rest on the circles; then, travel up and down and through alignments of circles. Circuit diagrams are thought to have influenced Walters, and the idea of switching is key. Curious figure/ground shifts occur as our brain tries to resolve whether to prioritise the lines or the circles. When we attend to the lines, our mind privileges the distinction between the contrasting colours, reading one or the other as figure, or oscillating between these alternatives. But we privilege the circles, we see them—positive and negative—collectively, as disruptions from the regularity of the striped field, which falls into the background. In some paintings we even link positive and negative circles jointly as a shape. The Koru Paintings’ great achievement is to hold these different formal possibilities in equilibrium, so they flicker under our scrutiny. This is not something Walters takes from Maori art, but is tied up in his particular stylisation of the koru.

The reception of Walters’s work is a complex matter. In the late 1950s and 1960s, the New Zealand art discussion is dominated by a search for national identity. ‘The big three’—Colin McCahon, Toss Woollaston, and Rita Angus—are local-landscape painters, and the big arguments are about New Zealandness. Abstract work is shown, but there is barely a discourse around it. It’s a blindspot. There is little understanding of modernist painting and the scene just doesn’t get formalism, preferring to see abstracts as symbols and emblems. While abstract painters like Milan Mrkusich are included in the New Zealand painting canon, their interests are not engaged by it. So, perhaps it is not surprising that, apart from his 1947 show at Wellington’s French Maid Coffee House, Walters does not exhibit in public until 1966, by which time the Koru Paintings are fully developed.

In 1969, Hamish Keith and Gordon Brown release their gospel, An Introduction to New Zealand Painting 1839–1967. Abstraction is mentioned, Mrkusich and Walters are mentioned, but the thrust of the book is elsewhere, promoting and entrenching the idea of a national school built around a representational landscape tradition. For a decade or so, the Introduction is hugely influential on the New Zealand art scene. But there’s resistance. The more-or-less-Greenbergian critic Petar Vuletic counters the parochialism of the national school idea, championing Walters and Mrkusich as the maligned real heroes of New Zealand art, and fosters a new generation of artists emerging in their wake. In 1972, he opens Petar/James Gallery in Auckland, to provide a more sympathetic environment for abstract painters to show in. With this move, formal abstraction seems to pull out of the mainstream of New Zealand art somewhat, to go its own way.

In the early 1980s, the tide turns and formal abstraction is belatedly recognised. In 1982, abstract painters claim the future in the presumptively titled show Seven Painters / The Eighties. In 1983, Walters gets a retrospective at the Auckland Art Gallery, then features centrally in its show The Grid. However, despite the fact abstraction is lauded as ‘internationalism’, the international discussion is moving in another way entirely. Figurative neo-expressionism and various post-modernisms are current. The idea of an inevitably abstract future is gone and Greenberg is now a dirty word. That’s a bit of a problem for the internationalist argument, or it should have been.

In the 1980s, Francis Pound becomes New Zealand’s most influential art critic. When Brown and Keith’s Introduction is re-released in 1982, with a new chapter but with its old biases intact, Pound savages it. Pound resents its nationalism and wants to praise whatever stands in opposition to it. So he asserts the international, both the modernist formalism of Walters and Co. (what was international then) and anti-modernist post-formalist post-modernism (what’s international now), skipping over the obvious philosophical clash. New Zealand is a time-lagged provincial art-culture playing catch-up, and a modernism (which understands abstraction as form) and a post-modernism (that wants to read it as sign) seem to arrive in the same breath and share the same foe. Walters gets caught in the conflation.3

Walters’s advocates assert his nobility in the face of the culture’s neglect: his work becomes synonymous with abstraction as a cause. His work is increasing centralised in the story and becomes increasingly collectible. If the New Zealand art market had once turned its back on abstraction, now it makes up for it: abstraction is seen as advanced taste. But no sooner has Walters attained his place in the sun than his work is challenged from a new quarter. As Maori issues hold increasing sway and as contemporary Maori art claims increasing attention, Walters (who has now largely stopped making Koru Paintings) is tried as an appropriator, for stealing the thunder from Maori art and for misrepresenting things Maori. The tone of the times is typified by Maori writer and academic Ngahuia Te Awekotuku, interviewed in Antic in 1986, who slates Walters for ‘plundering’.4

Heavily informed by Thomas McEvilley’s critique of the Museum of Modern Art’s 1984 Primitivism show, the New Zealand appropriation debate comes to a head with the exhibition Headlands: Thinking through New Zealand Art at Sydney’s Museum of Contemporary Art in 1992 (I was one of the curators).5 The show willfully presents Walters’s work alongside trailblazer Maori modernists like Para Matchitt (who was clearly influenced by Walters) and Sandy Adsett, in an attempt to reimagine his work as part of a wider national cultural discourse. However, it is less the show than Rangi Panoho’s catalogue essay that generates the furor. Panoho criticises Walters’s ‘programme of abstraction … which progressively simplified the [koru] form, divesting it of meaning and imperfection and distancing it from its cultural origins’.6 Panoho counterposes Walters as the bad appropriator with Schoon the good. For Panoho, Schoon treats Maori art respectfully, seeking understanding, while Walters takes without giving back. But it’s an arbitrary distinction. Sure, Walters drew on formal aspects of Maori art and he did not claim access to Maori cultural knowledge. But this could also be seen as respectful compared to Schoon, who presumed to regenerate what he saw as a dead tradition.

Paradoxically, rather than undermining Walters’s status, the debate proves crucial in keeping his work in the public eye, allowing its defense to be vigorously maintained. Walters’s supporters circle their wagons. In 1994, Pound publishes The Space Between, a book-length response. He marshals fascinating facts, but is anxious to consider them only in ways that advance a case against Panoho. If the appropriation debate was simplistic, now it becomes scholastic and arcane, turning on the relative weight and interpretative slant that can be given to details. Pound makes a lot of Walters’s and Schoon’s involvement as illustrators for the Maori Affairs Department magazine Te Ao Hou in the 1960s, countering Panoho’s suggestion that Walters gave nothing back. He skips the old argument—of Walters as an abstract painter unconcerned with the koru’s cultural values—to recast him a harbinger of biculturalism, a broker of a different brand of national identity. Pound’s case-for-the-defence involves such deftly spun arguments that the book ends up pointing to what it wants to deny—that there’s a problem here. But in a way, it doesn’t matter. The appropriation debate is a moral debate not an art-historical one. It doesn’t say anything about the qualities of Walters’s art and Walters’s art really has nothing to add to it: Walters’s work is not about ‘cultural issues’.

The debate swarming around Walters’s koru participates in its transformation from form into sign. Walters’s modernised koru is hugely influential on graphic designers: its reconciliation of opposing forms—black and white, circle and line—inform new emblems of cultural reconciliation.7 While the artworld argues about its cultural safety, the wider culture adapts the Walters koru as a badge of biculturalism.8 Designer Michael Smythe even proposes a new New Zealand flag based on it, arguing it offers ‘an astute metaphor for the bicultural basis of our nation. The black is distinguished by the presence of the white. The white is distinguished by the presence of the black … one colour comes to the foreground and flourishes. But it becomes infinitely enriched when that dominant colour backs off and allows space for the other to flourish alongside. It eloquently articulates the emergence of our nation.’ ‘This is not what Gordon Walters had in mind’, he adds.9

Walters’s work also becomes a sign in art. Starting in the late-late 1980s Julian Dashper quotes Walters’s aesthetic to express a nostalgia for a heroic modernism marginalised in New Zealand, literally so in a series of works in which he writes the date ‘1960’ using french curves. Others follow suit. And, in the wake of Headlands, artists—including young Maori artists like Peter Robinson and Michael Parekowhai—quote Walters’s koru as shorthand for the debates that now flow around it. (Walters’s 1968 canvas Kahukura and Parekowhai’s giant kitset version of it, Kiss The Baby Goodbye, 1994, both feature in the new APT.) Even those who hurry to Walters’s defense participate in his post-formalist undoing. In the wake of Headlands, jeweler Warwick Freeman designs his Walters-styled Koru Whistle (1993), ironically pitched to cultural whistle-blowers. ‘Rape whistles were in vogue’, Freeman recalls.10

After Walters’s death, Richard Killeen eulogises him in his 1996 Sue Crockford Gallery show, The Dreaming of Gordon Walters. Killeen’s paintings combine Walters-style abstracts with figurative images that rhyme with them. Killeen goes on to use Walters’s koru to represent all manner of things: corpses, canoes, war-plane insignia, and body armour. Killeen’s response to Walters is complex, even conflicted. Killeen has survived a major paradigm shift, evolving from a formal-abstractionist showing with Vuletic (with Walters as his mentor) in the 1970s into New Zealand’s pre-eminent postmodernist sign painter in the 1980s. His 2001 painting Local Face exemplifies but also critiques the transformation of Walters’s koru into a sign. Four blank white-male Identikit faces are given Walters korus for features. The korus are arranged into alternative countenances, happy and sad. The image carries suggestions of identity, criminality, blindness, and gagging.11 The alternative arrangements of the koru features recall the logic of Killeen’s classic post-formalist cut-out paintings, whose component images can be arranged in any order and are offered up for viewers’ free association, supposedly unencumbered by a sovereign authorial logic. Local Face deftly expresses Killeen’s ethical conflict, between his cut-outs’ ‘democratic’ ideals—that empower readers (the so-called ‘death of the author’)—and concern at what Walters has suffered at the hands of his readers.

The fate of Walters’s koru is at once fascinating and tragic. We are all familiar with the intentional fallacy: a work’s meaning is not what its author intended, but a function of the way it is received by and employed within the culture. But it is equally true that the Koru Paintings have become so totally subsumed by cultural issues that this has blinded New Zealand audiences to the way they operate as paintings, their formal-phenomenological concerns. While it has been argued that Walters appropriated and silenced things Maori by reading them in terms of his own interests, one can see that the culture appropriated and silenced Walters similarly. So, in showcasing a group of Koru Paintings, will the APT continue this process? Or, by presenting the Koru Paintings outside New Zealand and its thorny local politics, perhaps there is finally a chance that they might be enjoyed for what they are—works that remain to be seen.

.

[IMAGE: Gordon Walters Painting No. 1 1965]

- A few works feature vertically oriented korus. The 1972 painting Black Centre is rare in featuring upward and downward circular terminations on horizontal korus.

- Statement from the invitation to Walters’s 1966 New Vision show.

- Pound’s revision of New Zealand art history is more conservative than it appears. In focusing on Brown and Keith’s book, Pound suggests the debate in the early 1980s is still where it was back in 1969. In the process he obscures and downplays other domains of art inquiry that largely emerged in the 1970s: post-object art, contemporary Maori art, the women’s art movement, and photography. Compared with them, formal abstraction is only relatively marginalised.

- Shown a slide of Walters’s 1968 painting Mahuika, she famously complains: ‘I can only respond, at this point anyway as an individual and as a Maori, as a Maori woman. I think it’s damn cheeky! The insolence of the man is extraordinary! The gall! The sheer gall! Mahuika is … a lady of fire, of strength … and there she is, all black and blue! Frost in the night. Weird.’ ‘Ngahuia Te Awekotuku in conversation with Elizabeth Eastmond and Priscilla Pitts’, Antic, no. 1, 1986: 50. The matter of Walters’s titles is a gnarly one. According to legend, he frequently sourced his Maori titles from street names. His images were never intended to illustrate their Maori titles.

- ‘Doctor, Lawyer, Indian Chief: “Primitivism in Twentieth Century Art” at the Museum of Modern Art in 1984’, Artforum, November 1984: 56–60.

- ‘Maori: At the Centre, on the Margins’, Headlands: Thinking Through New Zealand Art (Sydney: Museum of Contemporary Art, 1992): 130.

- Walters himself designed a koru logo for the New Zealand Film Commission back in 1979.

- From 1984, New Zealand is defined by a perverse conflation of ideologies—New Right economic rationalism and biculturalism—and state agencies especially are rebranded with feel-good bicultural liveries. For Walters’s place in this, see Anna Miles ‘Peter Robinson, Gordon Walters, and the Corporate Koru’, Art Asia Pacific, no. 23, 1999: 77–81.

- ‘The Return of the Flutter Bug’, Listener, 21 February 2004: 29–30.

- Email to the author, 2006.

- See also Anna Miles, ‘Koru Koru Koru: The Freewheelin’ Richard Killeen’, Art Asia Pacific, no. 36, 2002: 40–5.

.

[I’ve made changes to this essay since it was published in Art and Australia, including correcting one major, glaring, rather embarrassing error. I originally referred to Ngahuia Te Awekotuku praising Chris Booth’s and Colin McCahon’s use of Maori imagery before she criticised Walters’s in her 1986 Antic interview. In fact, Te Awekotuku expressed concerns over McCahon’s work The Canoe Tainui, then went on to praise the beauty of Chris Booth’s work (saying its sense of land and space ‘makes it indigenous’) and McCahon’s Waterfalls (which do not use Maori imagery), before criticising Walters. Sloppy, sloppy, sloppy. My apologies to Ngahuia Te Awekotuku.]