Introduction to Giovanni Intra: Clinic of Phantasms: Writings 1994–2002 (Auckland and Los Angeles: Bouncy Castle and Semiotext(e), 2022).

–

Giovanni Intra will always be remembered for going out on a high in New York on 17 December 2002, following a friend’s opening at Metro Pictures. An overdose cut short the life and work of this charismatic artist, writer, and gallerist from whom so much more was expected. He was just thirty-four. In the space of a few years, Intra’s art-world odyssey had taken him from Auckland to Los Angeles, from the provinces of the art world to one of its new centres.

Back home, writing his obituary for the New Zealand Listener, Tessa Laird observed: ‘Giovanni Paolo Intra was fond of telling people that he was born in May 1968, the year and month of the famous Paris uprising, when art and anarchy ruled the streets. What Giovanni usually omitted from this romantic tale was that he was raised in Tūrangi.’1

Today, the North Island town has a population of 3,650 (fewer than Twin Peaks).

•

I first met Intra in 1990, while I was working as a curator at the National Art Gallery, in Wellington. He was completing his BFA in sculpture at Auckland’s Elam art school. He was five years younger than me, but it felt like a generation. Back then, Intra was scrambling punk references with the aesthetic of the wayside shrines he had observed on a trip to India the year before.

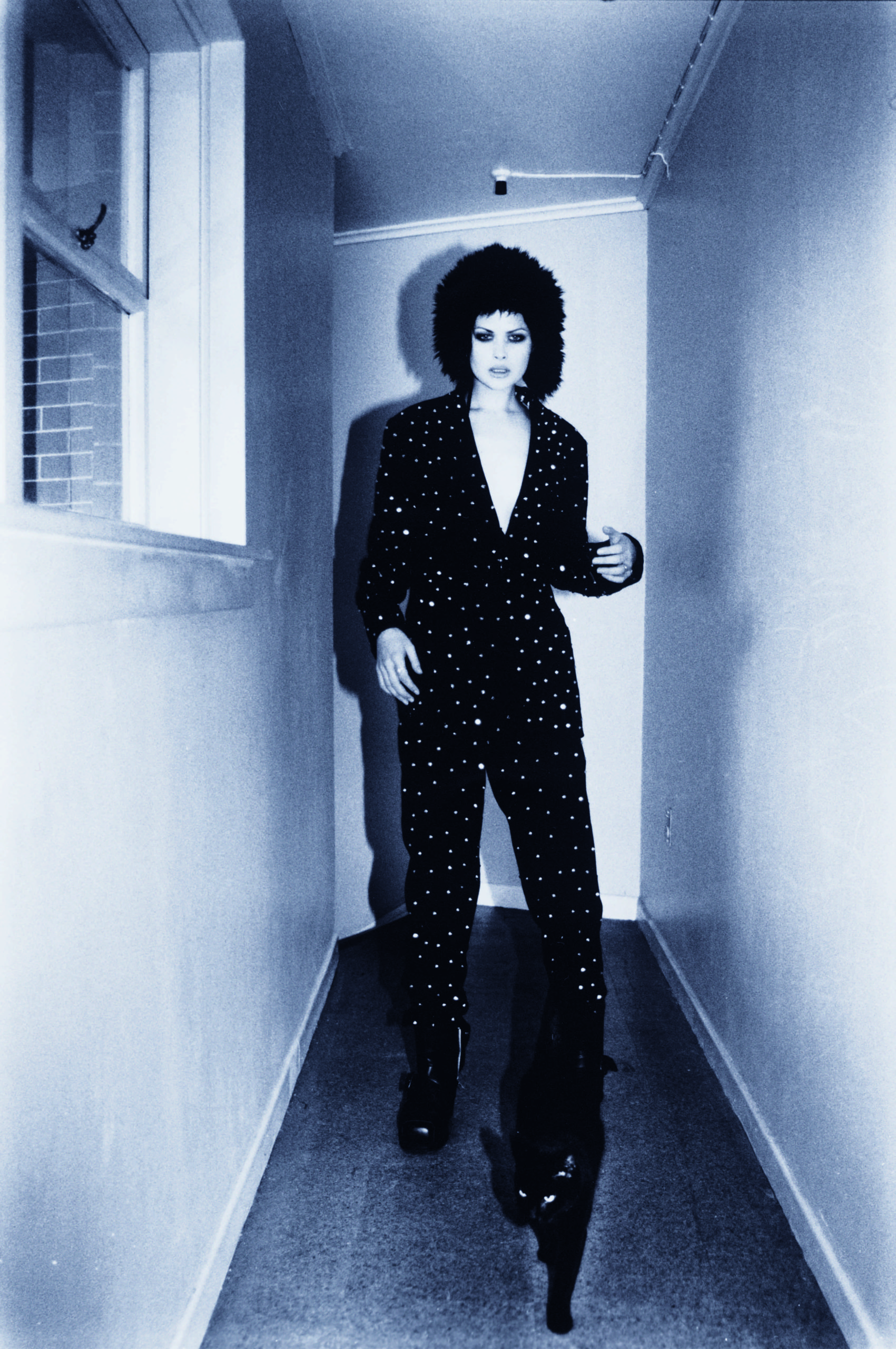

Intra’s best-known work from then is the studded suit he made to wear to the Elam ball. ‘The outfit was a huge success—even if the fastenings did leave the bare-chested Intra lacerated and bleeding by the end of the evening.’2 Intra exhibited his suit on a hanger, as Joseph Beuys had shown his dour felt suits. Where Beuys’s uniform exemplified an idea of artist as healer, Intra’s was transgressive—part punk, part S’n’M, part Liberace. The suit crossed over into fashion, featuring in an iconic fashion spread in Planet magazine, worn by a model accompanied by a bewitching black cat. After Intra died, the suit was jointly acquired by the Chartwell Collection and Auckland Art Gallery.

•

Intra was blessed with entrepreneurial can-do—a kiwi DIY attitude. In 1992, with a circle of artist friends, he founded Teststrip in Vulcan Lane. It may not have been the country’s first artist-run space, but it was new and dangerous. It proved the perfect platform for Intra’s subcultural inquiries and alternative activities. For the disorienting 1993 installation Waiting Room, Intra and Vicki Kerr surgically altered the space, curving walls, ceiling, and floor into one another, dousing them with antiseptic and cranking up the lights. Space evaporated in a hygienic white out, leaving nowhere for germs or shadows to hide. Visitors were asked to wear covers over their shoes.

Relocating to sleazy K Road the following year, tiny Teststrip would become the most talked-about gallery in the country—a treehut for the wannabe avantgarde. On the other side of the world, Artforum would publish an enthusiastic notice about the startup from supporter, collaborator, and publicist Stuart McKenzie: ‘Teststrip shows often tread a fine line between reporting and celebrating social dysfunction. There is a Nietzschean amorality here, and also a strenuous Romanticism in the style of Keats’ promise that til we are sick we understand not.’3

Linking punk, situationism, and surrealism, Intra’s art took diverse forms: a still-life arrangement of punk attire—Doc Martens, a studded cuff, and a cut-throat razor—in a vitrine; a Blood Mobile of red glass drips—a nod to Hans Bellmer; drawings with arcane citations and gimmicky hand lettering; product photos of medical paraphernalia indexed to the stations of the cross; a rotating CT scan of a pelvis accessed through a peephole viewer; a lab rat scratching away behind a wall of pink fibreglass insulation; X-rays and installations of smashed cameras. There were always lots of medical references, reminding us that the surrealists André Breton and Jacques-André Boiffard had been a doctor and a medical photographer respectively. And there were endless drug references, which now seem sadly prophetic.

As a young artist, Intra was provocative but successful—a rising star. Despite the punk posturing, he had supportive dealers, including surprisingly classy ones, such as Wellington’s Brooker Gallery and Auckland’s Claybrook Gallery. His work was acquired by prominent collections (public and private) and included in important exhibitions (featuring on the cover of the catalogue for the Museum of New Zealand’s 1994 survey show Art Now). While Chris Kraus emphasises the Teststrippers’ fuck-you attitude in her intro later in this book, Intra could really work a room. He was a charmer.

•

Writing became important early on. Intra’s art needed words. Texts featured in his hand- lettered, collaged, and photocopied drawings, posters, handouts, and fanzines. And, in 1989, he started contributing to the bFM student-radio magazine Stamp, cutting his teeth reporting on art, bands, comics, even a comedian. Between 1989 and 1992, he wrote for most issues: twenty-seven pieces in all. In addition to reviews, there were creative-writing experiments, including an invented interview with Picasso and an account of an imaginary historical woman artist who had slept with Picasso. A real artist took umbrage at being the subject of an invented interview, worried that fiction may pass for fact, requiring a disclaimer.

Stamp enabled Intra’s experimentalism and tolerated his in jokes. His writings there demonstrate his flair for parody. His piece ‘When You Sell Me’ was particularly scatterbrained: ’At the opening I wore my tweed coat, my polka-dot tie, my green trousers, my armour plated knickers, and I painted my nose red. / The artist rejects symbolism and borrowing from indigenous cultures, rather he attempts through a process of reduction and distillation to penetrate a common level of collective consciousness. / We know our positions too well. There is enough measured contempt and praise to keep our frustrations and pleasures balanced for a lifetime. / I’ll do the mail-out, you do the mail-out, she got sent a mail-out, he’s on the mail-out list, let’s hope the mail gets lost in the mail. / I fuck you and spit at you, you ruin me, you sell me, and this is the best art there ever is. / Everything would be totally diffgerent if the opportunity to sell out actually existed.’4

By 1993, Intra had quit writing for Stamp and was head down, completing his MFA dissertation Subculture: Bataille, Big Toe, Dead Doll, becoming more disciplined as a writer and reader. His text mapped the web of concerns he was exploring in his art—subculture and the iconography of revolt—via the now-available writings of Georges Bataille and the new commentaries on surrealism by Rosalind Krauss and Co. that appeared in their wake.5

In writing Subculture, Intra hit his stride as writer. In 1994, he began contributing to Midwest, a magazine I co-edited. For us, he wrote on painter John Hurrell, on surrealism and skin disease, and on Ava Seymour’s rubberist collages. He was always precocious and opinionated. He wrote about art that intersected with and extended his interests as an artist, but, if subjects didn’t fit, he could make them fit. In his Hurrell piece, he rejected the older artist’s concerns—postmodernism and provincialism—preferring to discuss the work in terms of situationism. Midwest also profiled Intra’s own work. We took him on as an artist-writer package. In 1994, Intra also met LA-based Semiotext(e) publisher Sylvère Lotringer. He was visiting his partner, the writer and filmmaker Chris Kraus, who was in Auckland making a film. Lotringer suggested Intra embark on a master’s degree in the fledgling Critical Theory programme at ArtCenter College of Design, Pasadena, where he was teaching. Escape became Intra’s plan.

In 1995, Intra began writing for the Sydney-based magazine Art and Text, becoming their New Zealand reviewer and review wrangler. It would become an important relationship. After doing just one review, Intra got to write a profile on fellow Teststripper Denise Kum. Art and Text had outgrown Australia and aspired to become a key international art journal. Looking for a bigger context, it too was plotting a move to LA. In 1996, it announced its arrival with its ‘Los Angeles’ issue. After frantic fundraising and securing a Fulbright Scholarship, Intra also landed there that year.

In LA, Intra stopped making art to focus on writing. At ArtCenter, he embarked on a thesis on Daniel Paul Schreber, the paranoid schizophrenic German judge who penned Memoirs of My Nervous Illness (1903).6 Intra quickly assimilated into the LA scene, but he kept exercising his New Zealand connections, and they him. He continued to write on New Zealand artists and for New Zealand publications, while taking on reviewing gigs for Artforum, Art.net, and Flash Art. For a while, his head was in both places. Oddly, it wouldn’t be until 2000 that he became a regular contributor for Art and Text, writing for them like clockwork.

•

In 1998, during a rave in the desert, Intra and ArtCenter friend Steve Hanson cooked up a plan to start a gallery. With some friends, they found a space in Chinatown, taking their name from the sign left by the previous tenant. Opening in January 1999, China Art Objects Galleries was instantly influential, elevating a new cohort of LA artists, including Jon Pylypchuk and David Korty, and leading the transformation of Chung King Road into a gallery district. Early shows included Laura Owens and Scott Reeder, Jorge Pardo and Bob Weber, Sharon Lockhart and George Porcari. There was a Stephen Prina record release, a Mike Kelley poetry reading, and a Mia Doi Todd concert. Intra was a midwife to a moment. Like Teststrip, China Art Objects was a platform. But, even after the place became successful, Intra’s existence remained precarious, his clothes op shop, his apartment grubby, his car impounded. Intra was no trustifarian, but he was energised by the game, continuing to hustle, banging out essay after essay on his old laptop.

•

Intra remained New Zealand art’s go-to person—our base camp in LA. He was forever hosting New Zealanders, and sponging off them—quid pro quo. His ethos was ‘transactional’. Intra parlayed Slave Pianos and Teststrip co-conspirator Daniel Malone into the China Art Objects programme and wrote on them. He also accessed LA artists for New Zealand galleries. He curated Span, with Diana Thater and Jessica Bronson, for me when I ran Artspace, Auckland. He helped place Eric Wesley into the Govett-Brewster Art Gallery’s 2000 show Drive, and David Korty and Paul Seitsema into Allan Smith’s 2001 Auckland Triennial Bright Paradise. He also wrote essays for all three shows.

Intra wore many hats, sometimes simultaneously. His texts were often advocacy and promo, written to support artist friends, artists he represented, artists he loved. His 1996 preview of Ann Shelton’s photobook Redeye describes it as ‘a charismatic exposé of the hideous truths and self-conscious mythologies of unemployed psychopaths who frequent Verona cafe and actually believe in drag’.7 He neglected to mention that he and Ann had been an item, that he was the subject of many of her images, that he was no stranger to Verona, and that he had been photographed in drag. But, as Intra became established and earned the opportunity to write on heavy hitters, the stakes got higher, and he couldn’t take as many liberties. His last pieces included insightful but respectful essays on Julia Scher and Isa Genzken.

•

Intra’s writing was informed by his appetite for theory, but it was never dense or abstruse. His writing had wit and verve; his insights felt intuitive and immediate. He also enjoyed mimicry. He had an ear for the edgy, disruptive prose of dadaists, surrealists, situationists, and punks, but also for their pompous, conservative critics. He enjoyed the battlefield rhetoric of manifestos and takedowns, toggling between formality and informality, snottiness and spit. The piece that opens this collection, ‘Journalism’, sets the scene. Made for a photocopied ‘micrograph’ to accompany a Tony de Lautour show at Teststrip, it has little to say about its subject, offering instead an absurd, adolescent mash of art criticism and pulp fiction. The text incorporates a patronising rejection letter from the editor of Harper’s Bazaar, Louis Leroy: ‘Sure, De Lautour has shrewdly reclaimed the moral high ground—head and shoulders above the usual chic critiques. But, as much as he in ates his own fame with his grin-and-bear-it portraits of disease, his basic thickness repudiates what he has done so much to justify in painterly terms. It is largely for intellectual reasons that we would not consider publishing commentaries on this kind of work.’8 In reality, Louis Leroy was the nineteenth-century art critic who christened an art movement by satirising its practitioners as ‘impressionists’.

Fictocriticism returned in 1997’s ‘For Paranoid Critics’, which casts the art world as a theatre of cruelty and payback for the critic: ‘One by one, each of your victims takes their revenge: Walter de Maria pelts your earlobes with one-thousand brass rods! Daniel Buren peels stripe-width strips of skin from your naked body! The Nutty Professor, played by Eddie Murphy, lowers the full weight of his body onto your right arm! Colin McCahon tattoos unspeakable passages from Revelation on your forehead! Linda Benglis throws you into a vat of boiling foam rubber! And Donald Judd drops you into a steel cube and then welds it up personally!’9

Intra was always drawn to the idea of the world as a paranoid projection. In 1995’s ‘Discourse on the Paucity of Clinical Reality’, he had recalled Breton’s formative experience as a doctor in a World War I field hospital: ‘Cases of mental distress, even acute delirium. These psychic casualties of war were the kind of cases that passed through the centre. One in particular struck Breton’s attention. A well-educated man, straight from the front, who had an astounding confession: the war, he said, was a complete sham. This testimony, which he elaborated in the most literary terms, did nothing but utterly convince Breton of the paucity of our own reality. This unnamed patient insisted that the gruesome hack jobs of the battlefield were nothing but skilful applications of prosthetic makeup, the shells flying overhead were only make believe, and the battlefield itself was the false counterpane of a set dresser. Upon hearing this, the soon-to-be leader of surrealism jumped back in his seat. The movement followed soon after.’10

Schreber also suffered from hallucinations. The paranoid Judge believed God was turning him into a woman in order to impregnate him and repopulate the planet. Schreber constructed a vast, novel cosmology to support his fears. His Memoirs is disorienting, detailing his experiences and accusations with surprising lucidly, scrambling insight with insanity. Intra called it ‘a cross between Napoleonic battle strategy and the Starr Report’.11 This mad, impossible book would become the basis of a case study by Freud that would prove foundational for psychoanalysis. After Freud had his way with Schreber, other theorists—including Jacques Lacan, Gilles Deleuze and Félix Guattari, and Elias Canetti—took turns making an example of him. As much as he wanted to rescue Schreber from their clutches, Intra would also make use of him, writing Schreber into essays on Slave Pianos and Julia Scher, as well as devoting two essays to him.

Schreber haunts other Intra pieces where he isn’t named: in Intra’s discussion of Salvador Dalí’s paranoid-critical method (where insights emerge in conflating inner and outer worlds), in his account of John McCracken’s minimalism (inspired by alien contact), and in his description of Mike Kelley and Paul McCarthy’s Sod and Sadie Sock (with its Salo-esque debauches).12 Intra’s interest in Schreber was keyed to paranoia as the engine of the art world, underpinning the way artists build their own worlds in their work as well as the wider scene’s sado-masochistic machinations.

In his obituary for Intra in Frieze, Will Bradley describes Intra’s Schreber thesis as an attempt ‘to suggest ways that art writing might be reinvented’.13 Intra certainly saw art writing as an invention, a game. A ne example is the reviews and CV of Pat Scull, a ctional artist. Intra ghost wrote them for a 1997 Danius Kesminas solo show, which posed as a two-person show with Scull. Casually presented in the gallery as a set of xeroxed documents, they supported the art-nerdy hoax. Aping the bogus fluff of reviews, they say everything but nothing: ‘Content to deliver quietly powerful work which is highly ambiguous in content, Scull provides a new form of artistic thinking for those of us who remain in the gallery, and retain our belief in the gallery.’

Intra’s Scull reviews and CV were the last pieces I found for this collection, and I only discovered them as a result of fact checking Intra’s Slave Pianos essay, which I had assumed to be a more-or-less straight piece of art history. In it, Scull is mentioned alongside real, canonical figures. Only by googling Scull did I uncover the con. Intra had playfully smuggled him—and, perhaps, a few other furfies—into the account, echoing the liberties Slave Pianos itself took with art history.14

•

The title spread of Intra’s 1995 Teststrip micrograph Untitled: The Poetics of Modern Reverie features a prophetic Samuel Beckett epigraph: ‘It’s suicide to be abroad. But what it is to be at home? A lingering dissolution.’ It’s juxtaposed with an image of the sealed souvenir glass phial of exotic-erotic Paris air—an atmosphere present but invisible and inaccessible—that Marcel Duchamp gave to the American collector Walter Arensberg.15

Intra’s thinking was informed by distance in space and time: being provincial (coming from New Zealand, away from the action) and belated (too late to be a real surrealist, situationist, or punk). Writing on Daniel Malone, he mapped cultural cringe as both malaise and strategy: ‘In New Zealand and Australia, segments of the population are afflicted by what is referred to as cultural cringe. Although this syndrome appears in many countries, these nations boast their own regionally specific varieties, as with tropical diseases. A complex that has not yet yielded a master list of diagnostic criteria, cringe is nonetheless a burgeoning field of study, and indeed practice … Paul Hogan of Crocodile Dundee fame is the patron saint of cringe, not for downplaying himself—as his identity is already paradoxical—but for the opposite reason: a hyperbolic intensity of character performed to sickeningly theatrical proportions. Cringe is to identity what wealth is to debt: the hallucination of prosperity, sophistication, and authenticity ascertained through an ironic hall of mirrors. Not so much the opposite of national pride, it is a perversion of pride.’16

Intra may have left New Zealand in search of a bigger context, but the transition wasn’t quite what he was expecting. It was more of the same. As much as he aspired to escape his small-town origins, in LA he simply found a larger village. In his catalogue essay for a New Zealand art show presented in out-of-the-way Missoula and Maui, he confesses: ‘My first wish for Los Angeles was that it wasn’t anything like New Zealand with its small, insular art world. Of course, my hopes were dashed as I rapidly discovered that all art scenes are horrifically regional in their imperatives: Los Angeles, just like New Zealand, is most signi cantly intrigued by the development of its own artistic mythology and, again like New Zealand, in the export of its mists to foreign shores. The doctrine of exoticism applies equally in both places.’17

Back home, Intra would himself become exotic (a figure of dinner-party rumour and speculation) and an exemplar (proof that escape was possible). Megan Dunn—director of Fiat Lux, an Auckland ARI that opened in the wake of Teststrip—remembers a note pinned to the wall of a Williamson Avenue share house in the late 1990s. It read: ‘Who the hell is Giovanni Intra?’

A new generation of New Zealand artists would follow in Intra’s footsteps, many enjoying success offshore. Intra’s posthumous profile in Metro magazine would be titled ‘Golden Boy’. It was riddled with errors—as befits a legend.18

•

After Intra died, friends in New Zealand and the US began talking about publishing a collection of his writings. The idea was repeatedly picked up, but stalled. It has now happened, twenty years on. More time has now elapsed since Intra died than he was writing for, making this book a time capsule—a guide to artists and ideas that animated the New Zealand and LA scenes of the 1990s—the way we were. In the intervening years, Intra’s writings have become even harder to find, being dispersed through defunct journals and obsolete catalogues, shipwrecked in library stack rooms and mouldering in vertical files. Clinic of Phantasms not only puts them back into circulation (giving them a second wind), it gathers them for the first time (exposing Intra’s trains of thought like never before).

In selecting the pieces for this collection, I bypassed Intra’s juvenilia and started in 1994, after his Subculture dissertation. I was keen to stress his voice over his subject matter, so I left out pieces where he simply served his subjects, preferring those where he could stretch out, saying something of his own in his own way. Towards the end, I included almost everything. It’s a variety show. There are informative pieces on key New Zealand and LA artists. There are think pieces, front-line reports, and a few blistering take-down reviews. There are also observations upon airplane terrorism and Mexican food.

Clinic of Phantasms will doubtless have a split audience. New Zealand readers may head first for familiar New Zealand stuff, and Americans for the American stuff, but I hope some readers will be energised by the quirky journey that linked them—Intra’s singular adventure as a writer, his personal wormhole.

- Tessa Laird, ‘34: A Tribute to Giovanni Intra, 1968–2002’, New Zealand Listener, 8 February 2003: 54.

- Kelly Carmichael, ‘Forget It, Jake. It’s Chinatown.’, NZ Edge, www.nzedge.com, June 2002. No longer online.

- Stuart McKenzie, ‘Junk Joint’, Artforum, March 1993: 40.

- ‘When You Sell Me’, Stamp, no. 13, September 1990: 4.

- The publication of Georges Bataille’s selected writings in English—Visions of Excess: Selected Writings, 1927–1939, ed. Allan Stoekl (Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press, 1985)—precipitated an explosion of interest in the work of the dissident French surrealist.

- Intra doesn’t seem to have completed his thesis. His academic transcript doesn’t list it and no one can find it in the ArtCenter library—although he graduated in 1999 anyway, a straight-A student.

- ‘Ann Shelton: Drive-By Shootings’, Pavement, no. 10, 1996: 10.

- ‘Journalism’, Tony de Lautour: Bad White Art (Auckland: Crushed Honey Press, 1994), np.

- ‘For Paranoid Critics’, PreMillennial: Signs of the Soon Coming Storm(Sydney: Darren Knight Gallery, 1997), 16.

- ‘Discourse on the Paucity of Clinical Reality’, Midwest, no. 7, 1995: 40.

- ‘Daniel Paul Schreber: Memoirs of My Nervous Illness’, Bookforum, vol. 7, no. 2, Summer 2000: 15.

- Intra taught a course on ‘Hallucination’ at the University of California, San Diego, in Fall 1999. He published the course outline: Giovanni Intra, ‘Contemporary Critical Issues: “Hallucination”’, Log Illustrated, no. 9, Summer 2000: 20.

- Will Bradley, ‘Giovanni Intra 1968–2002’, Frieze, no. 73, 2003: 54.

- ‘Slave Artists of the Piano Cult: An Introduction’, Slave Pianos: A Reader: Pianology and Other Works 1998–2001 (Frankfurt: Revolver, 2001). I’m reminded of an anecdote: ‘In a certain French convent, today, the novices permit themselves a perverse literary amusement. During the evening meal, as the others eat, one novice is entrusted with reading, out loud and in Latin, the Lives of the Saints. The game is to add additional tortures to the multitude already suffered by the martyrs in such a manner as to escape notice of the spiritual director supervising the reading.’ Allen S. Weiss, Iconology and Perversion (Melbourne: Art and Text Publications, 1988), 9.

- See Marcus Moore, ‘Marcel Duchamp and New Zealand Art, 1965–2007: By Means of Duchamp’s Peripheral Vision: Case Studies in a History of Reception’ (PhD thesis, Victoria University of Wellington, 2012), 209.

- ‘Daniel Malone: Triple Negative’, Art and Text, no. 70, 2000: 42.

- ‘Leaving New Zealand: The Question of New Zealand Art Abroad’, Te Ao Tawhito | Te Ao Hou: Old Worlds | New Worlds: Contemporary Art from Aotearoa | New Zealand (Missoula MT: Missoula Art Museum, 2000), np. This essay also opens with the Beckett epigraph.

- Tim Wilson, ‘Golden Boy’, Metro, May 2003: 66–73. ‘Friends and colleagues’ of Intra’s wrote a letter correcting Wilson’s errors. ‘Record Straight’, Metro, July 2003, 7–8.