Art Collector, no. 66, November–December 2013.

Caltech-based theoretical physicist Dr Sheldon Cooper is the lead character in the hit US sitcom The Big Bang Theory. He is a stereotypical geek (or, more correctly, a laughably extreme one). Cooper has a brain the size of a planet—he knows he is smarter than everyone else. Whenever he thinks he has trumped lesser beings—exposing their gullibility or inferiority—he lets them know by declaring, ‘Bazinga!’. Despite this, Cooper is bewildered by everyday social interaction. He had to devise a friendship algorithm to connect with others and wrote an epic roommate agreement to manage his relationship with his presumably less brilliant flatmate Dr Leonard Hofstadter.

The rise of technology is necessarily accompanied by the rise of the technocrat. Today, while Dr Cooper’s geekiness may be amusing, it is nothing to be ashamed of. Indeed, as social dysfunctionality is now recognised as mark of supreme intelligence, geeks can come out of the closet waving their Asperger’s test scores. You see their ascendency in TV detective shows. PC Plod has been replaced by lovable lateral thinkers with astronomical IQs—specialists, consultants, and backroom boys and girls. There is the neurotic-compulsive Monk, the hot-goth science-girl Abby in NCIS, the lab guys in CSI, the mathematician in Numbers, the arch-manipulator in The Mentalist, the genius inventor in Person of Interest, the blood guy Dexter, etcetera. Interestingly, the smug proto-geek Sherlock Holmes has been simultaneously reincarnated in England (Sherlock) and America (Elementary). Geeks abound.

In art, we are also seeing the emergence of a geek-and-proud sensibility. Anyone who gets about galleries cannot fail to notice an abundance of arcane works referring to science and science fiction; to mathematics and statistics; and to technology, computers, computer games, and the Internet. Endless bookish, laptop-bearing artists happily pursue the arcane, engage in inane pranks, and make their social bewilderment our problem. They are happy. Their time has come.

.

Botborg Equal parts techno-boffin and experimental videoand- music maker, Botborg’s performances use analogue video and sonic feedback to conjure an awesome variety of synesthetic audio-visual effects in real time, coaxing patterns out of scrambled collapsed signals. The Brisbane-based artist claims to follow the occult science of photosonicneuroeasthography, supposedly pioneered by Dr. Arkady Botborger sometime last century. A quick Google search, however, suggests that this is an elaborate fiction—a work of pataphysics.

.

Antoinette J. Citizen Melbourne artist Antoinette J. Citizen (not her real name) decorates galleries with computer graphics, so she can imagine herself trapped in a vintage video game. In her special-effects video, Artist in Studio, she imagines having awesome sci-fi powers: she brandishes a light sabre, is beamed up by a Transporter, and fires radiation beams from her eyes like Cyclops in X-Men. Citizen likes pranks. She forges signatures on prank letters to other geek artists, and, with artist Courtney Coombs, harassed the poor curators at Paris’ Palais de Tokyo for months with more pointless proposals than they could possibly deal with. Currently, Citizen is developing a Human Needs Meter (2011–), which adapts the look and function of the health bars in the 2009 computer game Sims 3 to the real world. In the game, these bars indicate the well-being of characters, in terms of ‘health’, ‘social’, ‘hygiene’, ‘energy’, ‘fun’, and ‘comfort’. But Citizen’s thought—that real people might log information into her wrist computer to help them determine that they are, say, dirty, hungry, or lonely—is absurd. Surely we know such things instinctively, without recourse to a computer.

.

Gabrielle de Vietri Back in 2004, Melbourne artist Gabrielle de Vietri sought to clarify and codify matters romantic. She had a lawyer draft a set of standard Relationship Contracts for different kinds of connections, including ‘Casual Fuck’, ‘Workplace Romance’, and ‘Meaningful’. Making these contracts freely available, she may have seen herself as offering a useful social service. But, although her contracts reveal detailed relationship analysis, they fail to understand our motivations for getting into them. Like Sheldon Cooper’s roommate agreement, they are contracts no one would want to sign, because something unspoken (bad faith, perhaps) is necessary to keep any romance alive. Recently, De Vietri has been writing stories using CAPTCHAs, those meaningless Internet passwords we are required to type in to prove to computers that we are human. Her tales are told in her video CAPTCHA (2010–2), where we see the original CAPTCHAs while hearing the stories. They include a steamy, suggestive romance in which ‘Desmodowe’ hankers for his beloved ‘Siseelly’. If you didn’t know that CAPTCHAs were used, you could imagine that the stories were written using jargon, an archaic or foreign language, or Klingon.

.

Daniel McKewen Brisbane artist Daniel McKewen has a Rainman-like penchant for statistics. For his video installation Top Ten Box Office Blockbusters of All Time, in Dollars, he screens the current ten top-earning films on ten monitors. Each film is overlaid with two sets of animated numbers: one tallies up the film’s budget, the other its earnings. It is hard to know what to pay attention to: the popular mythologies of these much-loved films or Hollywood’s compelling performance reports. The work is a labour of love for the artist, because, every time he shows it, he has to update it, as earnings increase and as new titles enter the top ten. McKewen’s fan-boy love of factoids also extends into the content of entertainment. In Conditions of Compromise and Failure (2011–2), McKewen plays armchair detective (or conspiracy theorist), using coloured threads on a pinboard to node map the labyrinthine interrelationships between characters in the US TV series The Wire. However, he completes this epic task in such obsessive detail that nothing is clarified. There are so many links, so many clues, that they cancel one another out. Information overload.

.

Danielle Freakley/The Quote Generator French semiologist Roland Barthes famously argued that texts are ‘tissues of quotations’. For a time, Perth’s Danielle Freakley/The Quote Generator spoke only in quotes, which she had collected into a book and memorised. In conversation, she would repeat the quote then cite her source, indicating that her words had been recycled from an often radically different context, for instance using Adolf Hitler’s words to express her thankfulness. Communication proved infuriating, for her and for others. The video records of her social experiment show Freakley exasperating one man who had the misfortune to be seated next to her on an airplane and confusing other people whose own reality we now realise is always already scripted, including a Captain Jack Sparrow impersonator.

.

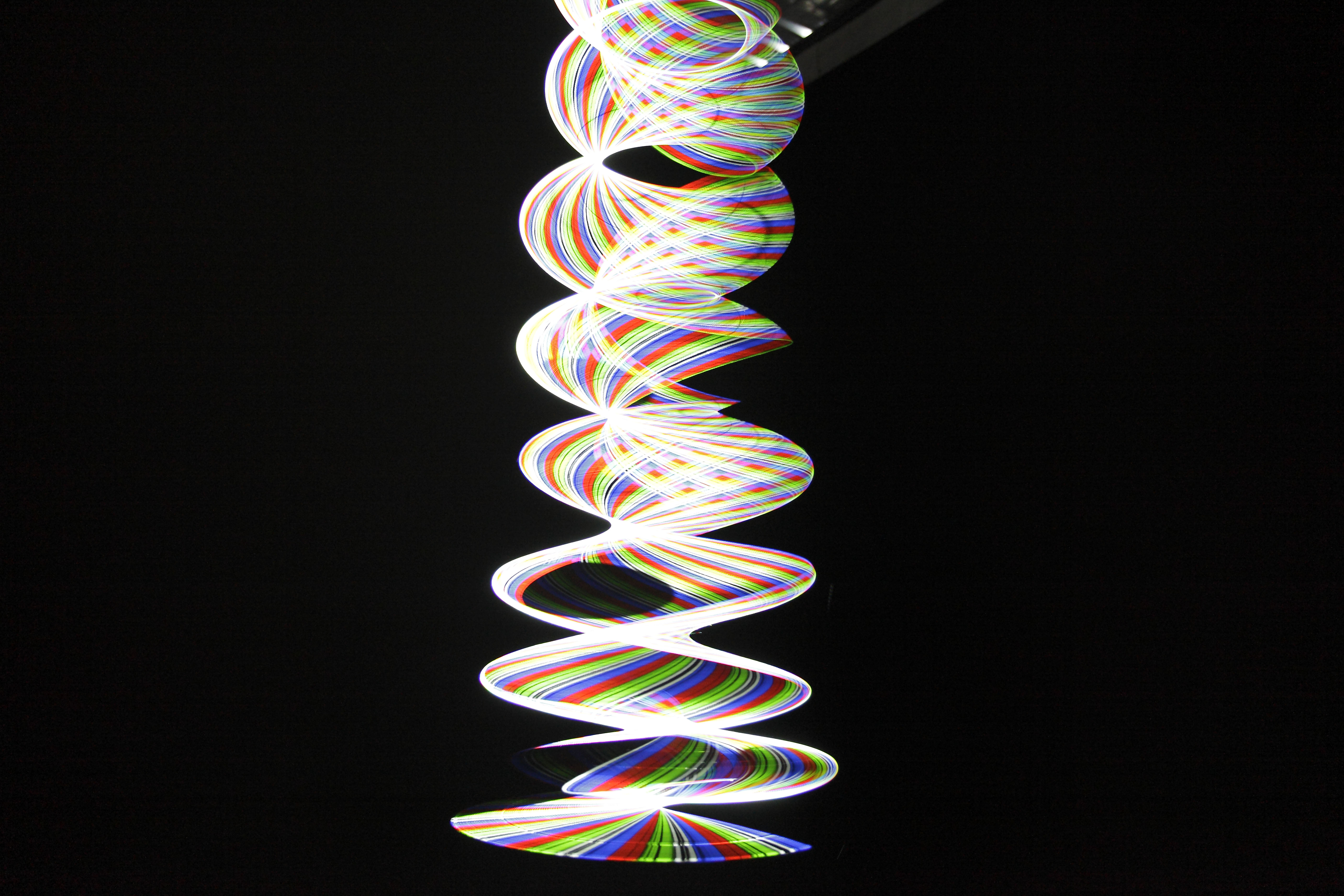

Ross Manning Brisbane artist Ross Manning plies us with eye-catching science displays, experiments in sound and light. Ever attentive to the quirks of technology, Manning noticed that DLP video projectors fire red, green, and blue light in rapid succession, knowing that our brains will mix them together to make white. For Fixational Eye (2011), he positioned a DLP projector to project white light onto a gyrating string. Fractionally separate in time, the red, green, and blue components hit the string at different points in space. Because of the ‘persistence of vision’, we see all the colours at once, separated in space. The work generates a prismatic, psychedelic effect, recalling, perhaps, Isaac Newton’s experiments in light refraction.

.

[IMAGE: Ross Manning Fixational Eye 2011]