Guarene Arte 2000 (Turin: Fondazione Sandretto Re Reubadengo Per L’Arte, 2000).

Gavin Hipkins is known for creating works from dozens upon dozens of near identical photographs or photograms. The subjects of the individual shots are apparently trivial, often childish—strips of plasticine, licorice straps, balls, lollies, buttons—and their compositions banal. But massed, marshalled, and regimented, the effect is epic. With their retro-modern styling, Hipkins’s works hark back to a moment when photography’s new ways-of-seeing were optimistically linked to a new vision of the modern world, both utopian (Rodchenko and Moholy-Nagy) and totalitarian (Riefenstahl). As if to underline the reference to heroic modernist engineering projects—architectural and social—Hipkins gives the works suggestive titles: The Tunnel, The Circuit, The Trench, The Track, The Movement …

Hipkins’s use of the definite article is pointed, suggesting these works are not just any example, but the primal, original, essential instance. And so the works stake a claim on necessity, even in the face of their overt contingency, making them portentous, even ominous. Their Kafkaesque inscrutability proves magnetic, drawing forth associations and confessions from us to fill the void. Like a psychoanalyst, or the monolith in Kubrick’s 2001, the works are presumed-to-know but are not telling. We speak for them.

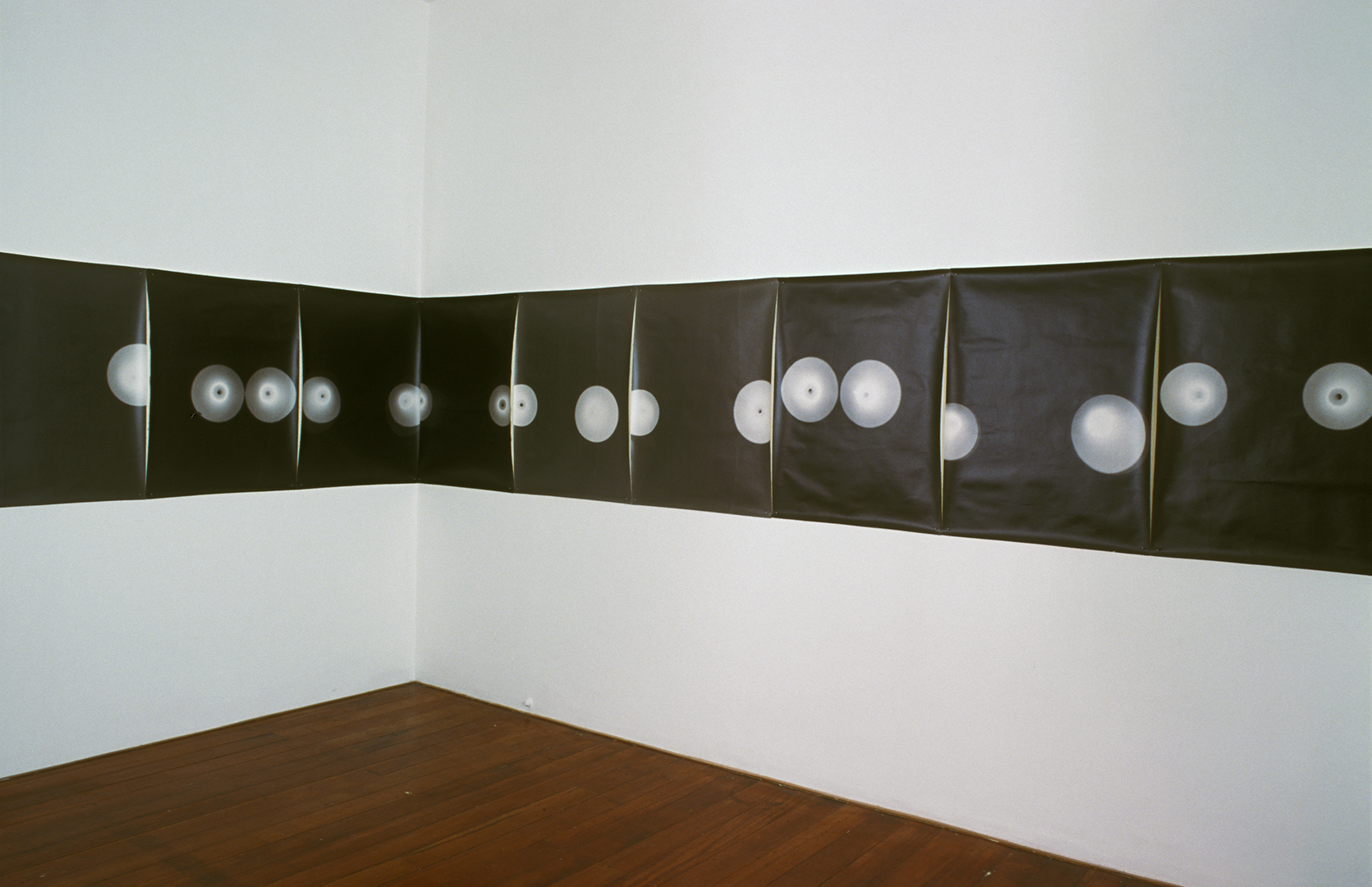

Take Hipkins’s latest piece, The Crib, a twenty-metre frieze of photograms of polystyrene balls. Prompted by the title, we will bring a range of associations to bear on what might otherwise seem to be a vacuous abstraction. ‘Crib’ is a word South Island New Zealanders use for their rustic holiday huts, which speckle the shore; it is the common name for Cribbage, a card game, where the score is kept by moving pegs down drilled holes on a board; a crib can be a wooden framework from which animals extract fodder; to crib an idea is to steal, plagiarise, translate, or summarise it.

Of course, the crib is most commonly the first bed, the cot where baby is confined. In New Zealand the bars of these little prisons are typically decorated with coloured balls which baby enjoys moving back and forth as a compensation while abandoned by mum—surrogate breasts. The paired milky disks in The Crib could also connote eyes, the reassuring super-vision of parental authority.

In its panoramic reach and willful obscurity, The Crib diminishes us, infantilises us, fences us in. It sends us to bed and makes us revisit those days when we struggled to comprehend the world, when we were just learning to see, just learning to focus. Significantly, the photogram—which registers a raw index of direct light, rather than focussing an image from reflected rays—is similarly a baby: a primitive photo-photography, a photography just beginning to see. And so The Crib could be understood as conflating the infant’s early days with those of photography. The Crib also resembles film footage, and, as we cast our eyes along the frieze, the globes palpitate. Rosalind Krauss has frequently noted an optical dynamism or agitation, a dissolving of the visual, that distinguishes certain early avant-garde art, and has linked it to the child’s fascination with flickering photo-cinematic toys such as the zoetrope. But The Crib’s kinesthesia is not ultimately satisfying. It is mesmerising yet forlorn, sexy but inhuman: a sterile jiggle, an already spent eroticism, a rerun. If The Crib is a time machine, returning us to some formative moment in the development of the modernist subject, it cannot erase hindsight. We can’t really go back, can’t view the world through the wide eyed photo-utopianism of Laszlo Moholy-Nagy. And the bouncing balls of The Crib are insufficient compensation.

Hipkins’s charismatic crypto-fascist works offer us something slight but compelling on which to hang speculations such as these. They are generic mysteries in which we locate what concerns us, while embracing it as other. So the works’ significance is less the hermeneutic labour they routinely occasion—one which the artist himself happily shares in—than that they call it forth, and how they support it. Hipkins provides a format.