Art News New Zealand, Winter 2021.

–

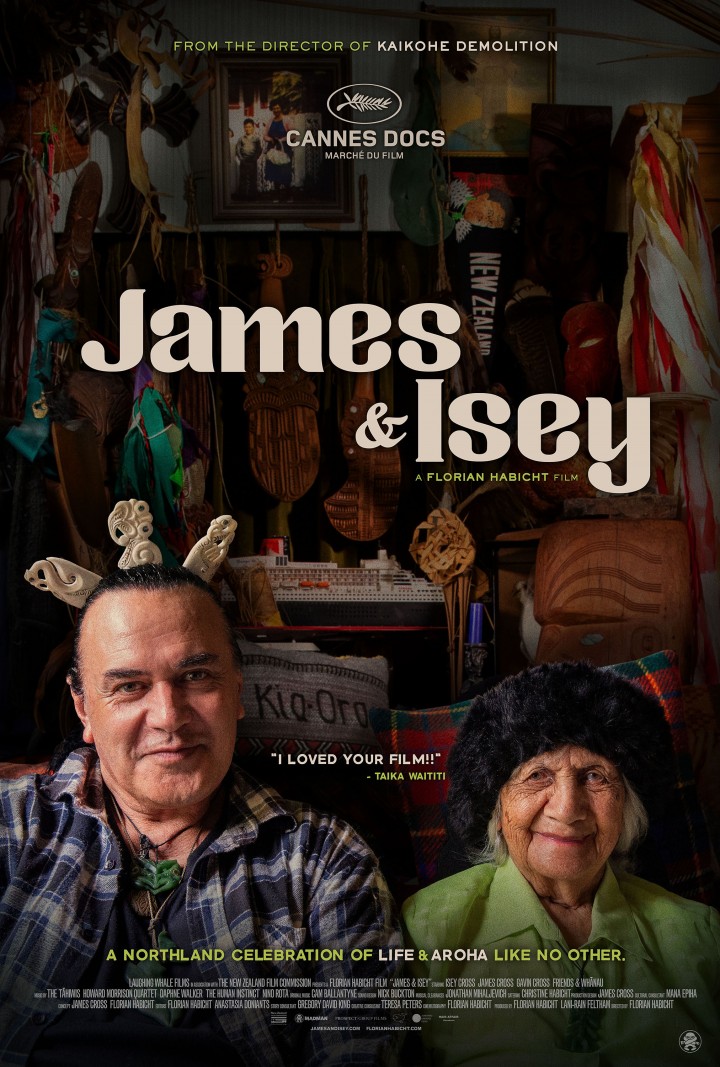

Florian Habicht’s new film James & Isey—a documentary about a son organising his mum’s hundredth birthday party—opened on eighty screens around the country.

.

Robert Leonard: How did James & Isey come about?

.

Florian Habicht: Long story. I was having a tough time. I’d had a big success with my 2014 film Pulp: A Film about Life, Death, and Supermarkets and had offers to make more band films, but I decided to come back to New Zealand. I made Spookers (2017), a documentary on people who work at the Auckland scream park, but it bombed commercially. Then, I was struggling to get my new drama, Under a Full Moon, made. I thought I could self fund it and shoot it with a small crew. But, when we went up north, everything that could go wrong did. If we’d filmed that, it would have been a cult film. A week in, I pulled the plug. All our savings went into that shoot. My partner, Teresa Peters, was supportive, but I feared she would dump me, because I was this mad man, trying to pull off an epic shoot with a tiny crew. It was a low point.

After that, I wanted to have a quiet, normal life. I joined Curious Film and made TV commercials. I made two car-safety campaigns. One featured people at a car yard unselling cars. For the car salespeople, we cast real-life paramedics and police—people that attend accidents. And, for the car buyers, we used real people who didn’t know what was going on. They thought they were going to a car yard to buy a car. It was a successful campaign.

Then they wanted a director who could work with real people to do an Instant Kiwi campaign. The idea was: people across Aotearoa sharing their Instant Kiwi stories—how they play and what do they do to bring them luck. That’s how I met Isey Cross. We were casting and I got a postcard from Kawakawa: ‘Hi, my name is James. I live with my mum. She’s turning 100 in a few months and we play Instant Kiwi, and, if you cast us for your commercial, Mum promises to bake you one of her famous apple cakes.’

When I got James and Isey’s audition tape, it was like a little documentary. One of my questions was: if you could take one thing from this life to the next, what would it be? James said: ‘My mum.’ Then, when we made the ad, and James asked me to film Isey’s birthday party. He’d approached a couple of people already, but they wanted to charge too much. I said I’d love to do it, no charge. I’d promised myself no more docos for a while. I just said I’d film the birthday party, but, in James’s mind, I was already making a whole film.

.

What impressed you about the duo?

.

I’ve spent years writing scripts, but, when I met James and Isey, it was like, ‘Oh my God, you can’t script this.’ Their chemistry! They’re a comic double act. James loved Knight Rider as a kid and he’s got a car called Black X that looks like Kitt. And they both wear 1980s outfits. The whole time I filmed them, there was never a moment where things settled down or got boring.

.

The film is structured chronologically. There’s separate chapters for each day in the week leading up to the party—a countdown.

.

Sometimes it takes me ages to come up with a structure, but this came to me during the shoot. It was a really simple device.

.

The opening sequence is languid, with a long take of horses with subtitles sketching out Isey’s life history.

.

There were no images of Isey from when she was young, so we showed these horses, while people read about her life. When Isey was young, she would ride her horse from Kāretu into Kawakawa. Then she got her pink 1973 Holden Premier. They only have cows on the farm now. The wild horses on the beach come back later in the film, when James visits Spirits Bay. I got pressure to make the opening bit go faster and it almost got cut. But, now, when I ask people which is their favourite bit, they often say the beginning. The idea wasn’t mine. It was Jarvis Cocker’s. He watched an early edit and said it would be nice to contextualise Isey within history. What was Isey doing when people were landing on the moon?

.

So, in Cocker’s promo quote for the film—‘A truly alternative (and uplifting) history of the twentieth century’—he is applauding his own idea.

.

Ha. Yes, he is. But I love that idea. The opening gets the past out of the way, because the film’s not about the past. Isey lives in the present; she refuses to look back. To get Isey to live so long, James is always talking about the future. A week after her hundredth birthday, he was ordering the chairs for her 101st. Seriously.

.

There’s an early scene of James killing and burying a sick cow. It’s a morbid note, which you ultimately leave behind, because it’s not a film about death.

.

James is so affected by the cow’s death—it shook him up. When his animals die, he gives them a proper burial. What I didn’t realise, when I was editing, was that, from that scene, audiences would be wondering whether Isey would even make it to her birthday. People sit right through the end credits to check that Isey is still going strong.

.

I’m amazed that you can make a film entirely on your own and present it at cinema scale.

.

It feels like a miracle when I see it on the big screen. I shot it with no crew and edited it on my laptop. It was so direct. I didn’t tell anyone I was making it until I had a rough cut. Some shots are bumpy, because there was no time to think. The magic was happening and I had to capture it intuitively. When the camera’s shaking, it’s because I’m laughing. It’s shot using old Russian Lomo 35mm cinema-camera lenses so the picture’s beautiful and imperfect. Not everything’s sharp.

.

Isey is the stable centre of the film, while our understanding of James lurches about. He’s this, then that, then something else again.

.

His personality is so rich. The film is the tip of the iceberg. James wants to make a sequel with me. I also have ideas for a sequel, but I’m keeping them to myself.

.

James and Isey are showoffs, attention seekers, playing up to the camera like naughty children. I assume Isey doesn’t go marlin fishing every week.

.

She wouldn’t have gone fishing if I wasn’t filming, but, when we went, it was one of the best days of her life. She looked so happy. James loves showing off. Wherever he goes with Isey, he tells strangers, ‘My mum’s a hundred.’ And Isey, disgruntled, says, ‘Don’t mention my age!’

.

One has to wonder if James is for real—he’s so theatrical. He claims to be a tohunga and shaman, speaking in ancient tongues, but we don’t see others endorsing this. Then he’s weeing in the backyard, driving Black X, and ordering McDonald’s. Maybe he’s a tohunga, maybe he isn’t. From the film, many won’t know. Does it matter?

.

If it matters, that’s up to audience members individually. For me, it makes the film interesting. I’ve never had trustworthy subjects in my docos, not even for the Pulp film—that’s what makes the films and the subjects special. I also like juxtaposing extremes. It’s why the McDonald’s scene is powerful, coming after the marae visit. James is complex. People have different responses to him. At one screening, a Christian woman was so moved by him that after the credits she stood up and spoke in an ancient tongue. But, there are people who see his language as a product of colonisation and the loss of te reo. Everyone is entitled to their thoughts.

.

The scene of James holding out his phone showing old video footage of himself as a lounge singer, covering Duran Duran is amazing, cheesy, and confronting—him in the present framing this past, before and after.

.

He showed me the footage on his phone and I immediately thought let’s shoot it in the street, because it’s always good having things moving in the background. Then, I thought, if he’s in his car, there’ll be traffic in the background. So we drove into town and did it in one take. I had to write to Duran Duran to get permission to use ‘Hungry Like the Wolf’. I said the film would only be big in New Zealand.

.

To me, James and Isey seemed exotic, remote, living in a bubble. But that collapsed when I saw them engage with people I knew: Jacinda Ardern and Kelvin Davis (a relative), and then Matiu Walters from Six60 is at the party (another relative). Suddenly, they’re connected.

.

James’s dream was to be a famous, sexy singer, like Matiu. He certainly had the talent. But there are so many factors at play when it comes to finding success, or it finding you. It makes me happy for James that our film has been more successful at the New Zealand box office than the Six60 film. More people went to see the unknown mother-and-son duo from Kawakawa than our most famous band.

.

There’s a lot of tragedy in James’s life. He had a stroke. He had to come back to care for his father, then his mother.

.

Maybe that’s why Isey refuses talk about the past. Colonisation is the other tragedy in the film. The racism James describes and Isey being forbidden to speak Māori at school is heartbreaking.

.

And yet that bleak stuff also seems to be there in order to be overcome. Despite everything, it’s an optimistic film. Isey says, ‘Don’t worry, be happy.’ That seems to be an overriding message.

.

Colonisation can’t be ignored, but the film is about aroha.

.

The scene of James and Isey and Isey’s older son Gavin in the car in the garage feels nostalgic, recalling a childhood playing in parked cars. I was reminded of Taika Waititi’s Two Cars, One Night (2003) and his Blazed ad (2013), and that great scene in your film Kaikohe Demolition (2004).

.

Maybe it’s a coincidence. That scene just happened. When it did, I knew it was like the scene in Kaikohe Demolition. But then, it’s also like my NZTA ads with people in parked cars. I reused the Human Instinct soundtrack from Kaikohe Demolition for that scene—Billy TK, the Māori Jimmy Hendrix.

.

You’ve got a connection with Northland. You spent your childhood there.

.

We moved to Paihia when I was eight, and I was there until I was seventeen. I used to think home was anywhere in the world where I had my suitcase. But I’ve spent a lot of time up north recently, reclaiming my roots. And I made all my early films there. I feel happiest there. I’ve made friends with birds in the bush. The further north you go, the more special it gets. Just being able to go up to Cape Reinga.

.

As a child, were you engaged with Northland’s Māori communities?

.

Yes and no. As a child, some of my friends were Māori. But Paihia is a more Pākehā place, Kawakawa’s more Māori.

.

James & Isey is a feel-good film, but it owes something to a timewarped ‘Ten Guitars’ view of Māori. You use Daphne Walker’s song ‘Haare Mai, Everything Is Kapai’, from 1955 and James sings the Lou and Simon song ‘A Māori Car’ from 1965.

.

That’s James and Isey’s Northland. It’s like going back in time. Lots of the music in the film is from Isey’s era. It opens with the Howard Morrison Quartet singing ‘He Kainga Tupu’ (Home Sweet Home). The lyrics are perfect for James’s journey. The Tāhiwis’s cover of Arthur Freed’s ‘Should I?’ would have been a pop song in Aotearoa back in the day. Isey would have been a teenager. The Tāhiwis recordings are from the 1930s and haven’t been featured in a film before.

.

James & Isey feels like an antidote to Vincent Ward’s In Spring One Plants Alone (1980). There’s a connection in terms of subject matter—a Māori mother and son living together in a remote setting, observing their daily rituals—but it couldn’t be more opposed in feeling. In Ward’s film, the old woman is the carer for her son, who’s schizophrenic and violent. In Spring feels bleak; James & Isey uplifting.

.

After making James & Isey, I watched In Spring, because friends said I had to. It feels so different. Leon Narbey shot In Spring using a long lens. He was far away from the action for the whole film. But, with James & Isey, I’m in the film with them. I didn’t have a sound recordist and the mic was on the camera. I wanted good sound, so I had to be extremely close.

.

Today, there’s anxiety about Pākehā representing Māori, rather than them framing themselves. But James & Isey complicates this, because you became an instrument for your subjects to depict themselves.

.

I’m not representing Māori, I’m creating a portrait of two individuals. I’m celebrating and capturing their magical world without judgement, as I did with Warwick Broadhead in Rubbings from a Live Man. And, yes, I do become an instrument of sorts. James approached me to make the film. He determined that we include Tāne Mahuta, Spirits Bay, and Te Rerenga Wairua (Cape Reinga) to bring the spirit world on board. He was creatively involved with the making of the film.

.

There’s a parallel with your drama Love Story (2011), in which you ask random people what they think should happen next and film that. But this is also a distinctive aspect of your cinema.

.

That’s true. With Love Story, I let my subjects—the people on the streets of New York City—dictate the film’s narrative. They were stand-ins for the audience, so when you watch the film, it feels like a pick-a-path book. It’s become the way I make my hybrid docos. In Rubbings from a Live Man, Warwick came up with his own cast of alter egos, and he performed the entire documentary—or ‘fuck-you-mentally’ as he called it.

.

As a filmmaker, you walk a line between sympathy and detachment, with abrupt shifts in tone, from hand held documentary scenes to grand cinematic fantasy ones, like the scenes at the waterfall and Te Rerenga Wairua. We are jolted out of reality and into James’s head, into his fantasy.

.

Kaikohe Demolition has those shifts too. It’s part of my language. That these more cinematic scenes signal a shift into fantasy is your interpretation. James and Isey are nuanced human beings and nothing is black and white in the film. That’s what makes James & Isey still interesting for me, after watching it a hundred times.

.

Isey sings ‘Que Sera, Sera’. Doris Day sang it in Hitchcock’s The Man Who Knew Too Much (1956), where she is a mother calling out to her kidnapped son. ‘Que Sera, Sera’ has been described as ‘cheerful fatalism’.

.

I haven’t seen the Hitchcock film, but I’ve read about it. ‘Que Sera, Sera’ is Isey’s philosophy. James is always giving her his big ideas for the future but her response is always, ‘Que Sera, Sera’. She’s happy with whatever happens. It was hard getting that song. A big chunk of the film’s budget went towards the rights.

.

What will your future be? You’re still planning to go back and make dramas, despite your success with James & Isey.

.

I just made a video called Waves. During the James & Isey shoot, I slowed down and captured life in Isey’s pace. I felt like a David Attenborough wildlife camera person. When you briefly see the sun setting in the film, I probably filmed the sun for an hour. That kind of meditative filming inspired Waves, which is fifty-two minutes of waves, basically. It’s inspired by the forces of nature being greater than us all. It’s going to be on the giant video screen in Fed Square, in Melbourne, for a week in September. And yes, I’m doing drama. In 2012, I read the book on the ‘inner movie method’, How to Write a Movie in Twenty-One Days. I enjoyed it and recommend it, but I’ve been working on one of my scripts for seven years and the other for nine. The revision of Under a Full Moon—my ‘Titanic’ film-shoot experience—is ready to go, but I need financial support.

.

Do you think James & Isey has an international audience?

.

Yes. Jarvis Cocker and his girlfriend Kim loved the film. So did other European friends. But, so far, the big decision makers don’t think so, apart from Australia. I’m going to show it to Mubi and Netflix soon. I thought Kaikohe Demolition would have an international audience, but it was ‘too New Zealand’. It played in New York at the Margaret Mead Film Festival at the American Museum of Natural History, and that was about it.

.

I went to the James & Isey premiere at the Civic. Half of Kawakawa seemed to be there.

.

The Bay of Islands kapa haka group was the highlight for me. Weren’t they amazing? James wanted to have the premiere at the Civic, partly because it’s so grand and partly because the last time Isey went to the movies it was at there during World War II with her brother Len. Our distributor, Madman, said it’d be easier having the premiere in Newmarket or Kerikeri, but James only wanted it at the Civic. We asked and it was a definite no, unless we did it in winter. Most dates also had about five pencil bookings. Then a date opened up and it just happened to be Isey’s 102nd birthday!

.

Will the film change James and Isey’s lives?

.

I don’t think it has changed Isey’s, except that strangers come up and kiss her. She doesn’t like that at all. I think she would have been happy to have a little party for the premiere. She didn’t need a thousand people at the Civic, but she did enjoy it. At 11:30pm, she got on stage in the Wintergarden and was dancing. I thought she’d be tired, but she was up for it. James, on the other hand, always wanted to be a movie star. When he saw his first cowboy movie as a kid, he heard a voice saying, ‘Become a movie star.’ He was singing in a band in Las Vegas and acting and it was going well, but he gave it up to come back and look after his parents. But now, from him putting his family first, that dream has come true. He’s in the ultimate movie—with his mum.